ResNet(

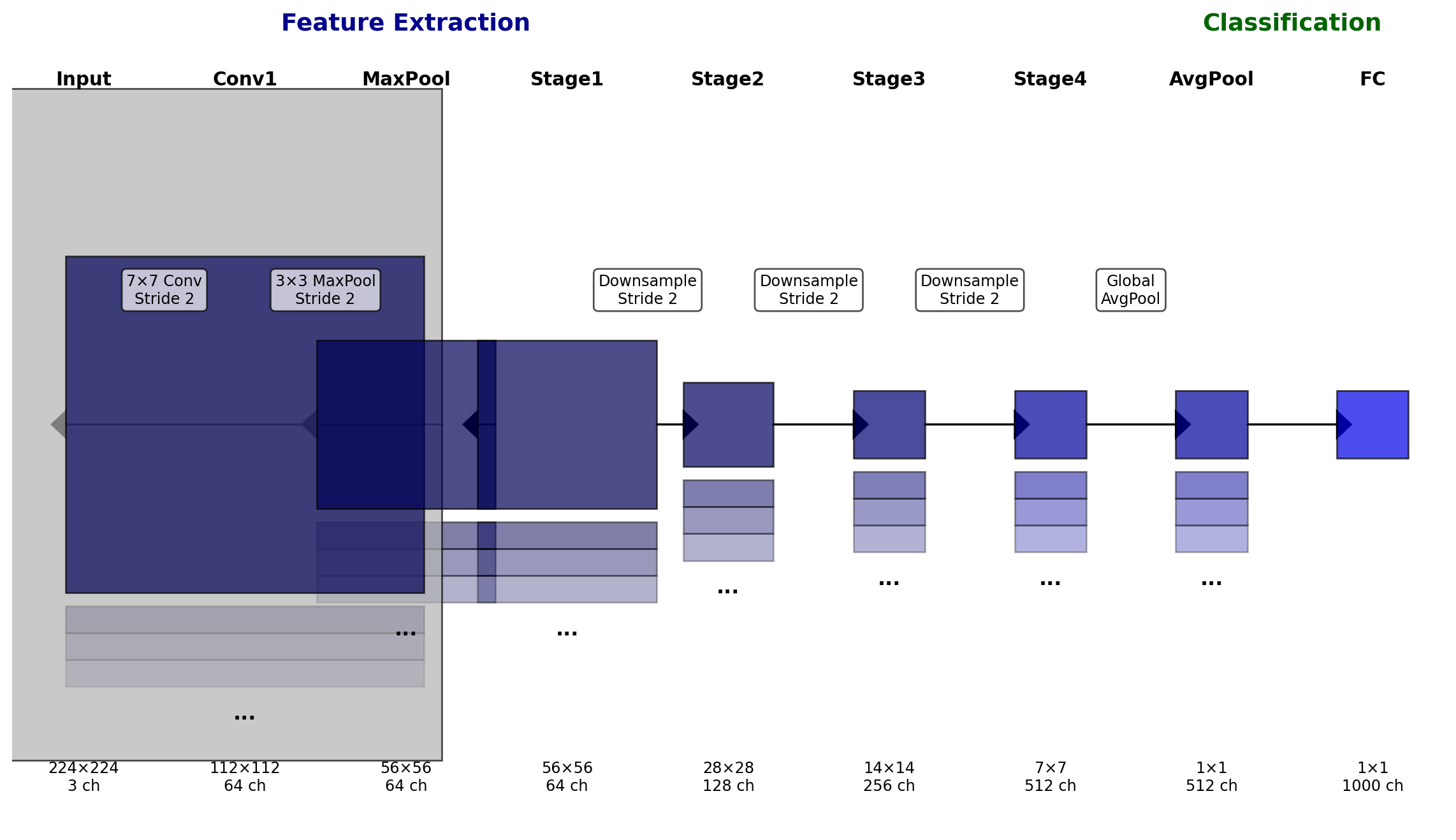

(conv1): Conv2d(3, 64, kernel_size=(7, 7), stride=(2, 2), padding=(3, 3), bias=False)

(bn1): BatchNorm2d(64, eps=1e-05, momentum=0.1, affine=True, track_running_stats=True)

(relu): ReLU(inplace=True)

(maxpool): MaxPool2d(kernel_size=3, stride=2, padding=1, dilation=1, ceil_mode=False)

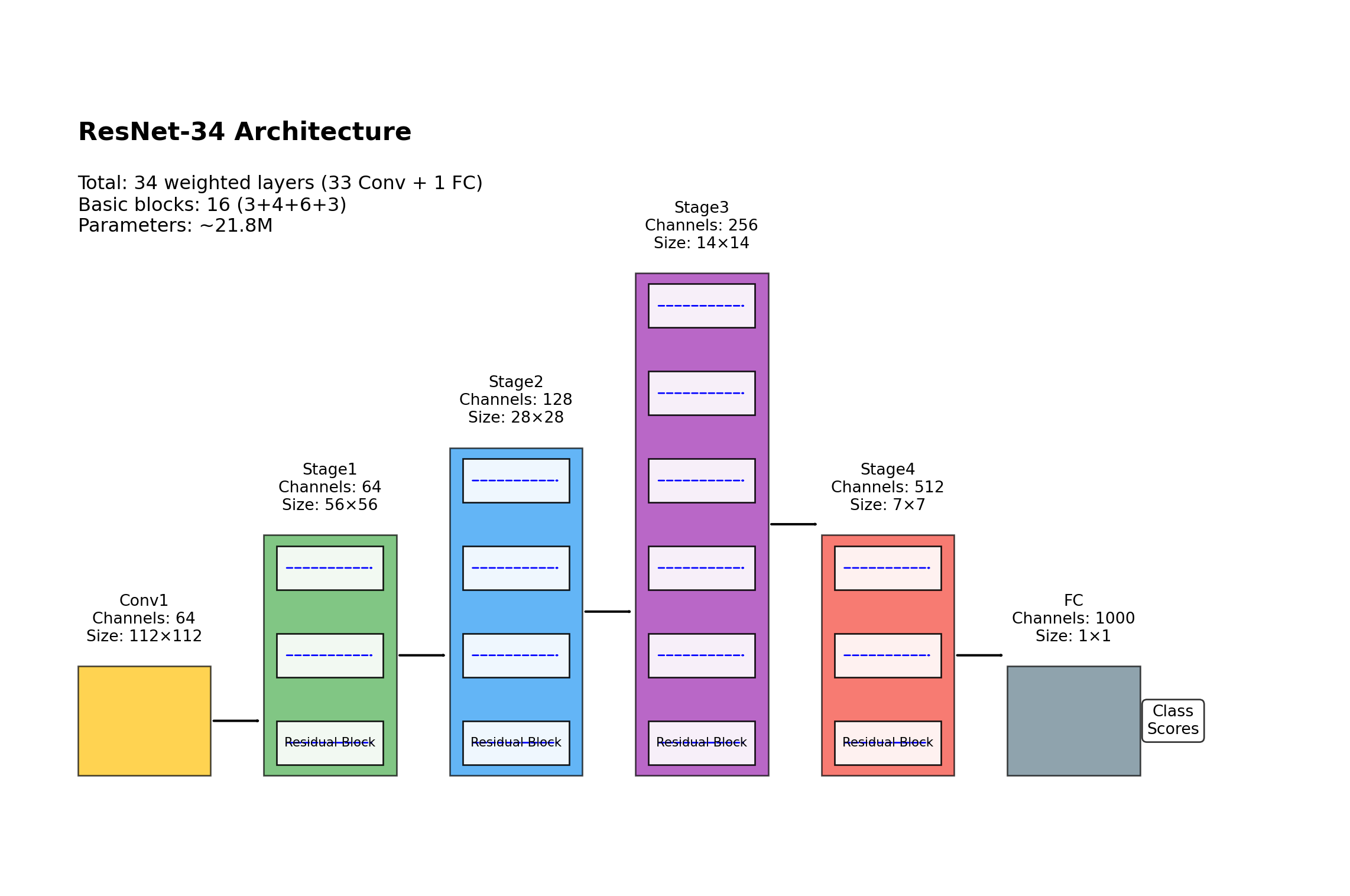

(layer1): Sequential(

(0): BasicBlock(

(conv1): Conv2d(64, 64, kernel_size=(3, 3), stride=(1, 1), padding=(1, 1), bias=False)

(bn1): BatchNorm2d(64, eps=1e-05, momentum=0.1, affine=True, track_running_stats=True)

(relu): ReLU(inplace=True)

(conv2): Conv2d(64, 64, kernel_size=(3, 3), stride=(1, 1), padding=(1, 1), bias=False)

(bn2): BatchNorm2d(64, eps=1e-05, momentum=0.1, affine=True, track_running_stats=True)

)

(1): BasicBlock(

(conv1): Conv2d(64, 64, kernel_size=(3, 3), stride=(1, 1), padding=(1, 1), bias=False)

(bn1): BatchNorm2d(64, eps=1e-05, momentum=0.1, affine=True, track_running_stats=True)

(relu): ReLU(inplace=True)

(conv2): Conv2d(64, 64, kernel_size=(3, 3), stride=(1, 1), padding=(1, 1), bias=False)

(bn2): BatchNorm2d(64, eps=1e-05, momentum=0.1, affine=True, track_running_stats=True)

)

)

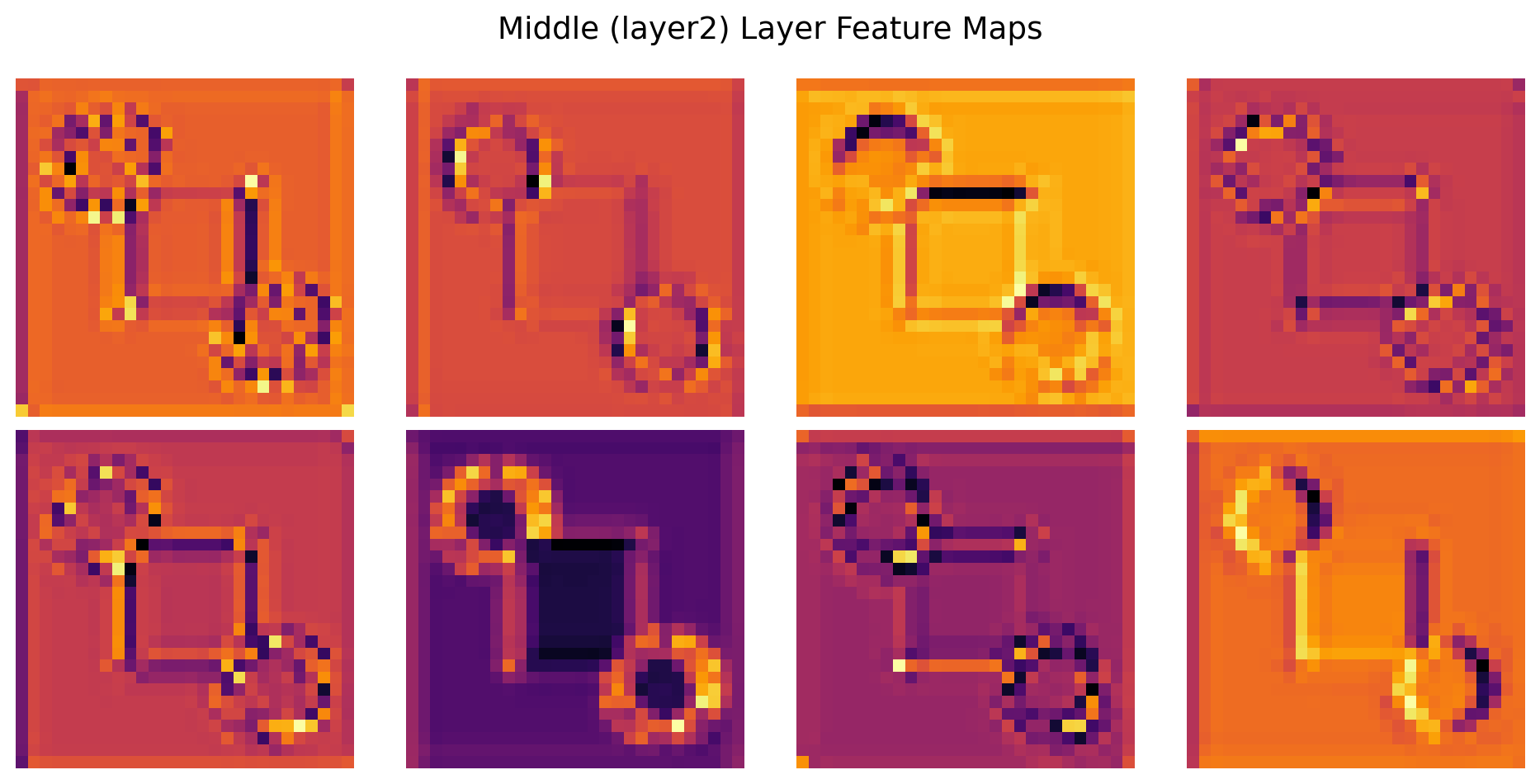

(layer2): Sequential(

(0): BasicBlock(

(conv1): Conv2d(64, 128, kernel_size=(3, 3), stride=(2, 2), padding=(1, 1), bias=False)

(bn1): BatchNorm2d(128, eps=1e-05, momentum=0.1, affine=True, track_running_stats=True)

(relu): ReLU(inplace=True)

(conv2): Conv2d(128, 128, kernel_size=(3, 3), stride=(1, 1), padding=(1, 1), bias=False)

(bn2): BatchNorm2d(128, eps=1e-05, momentum=0.1, affine=True, track_running_stats=True)

(downsample): Sequential(

(0): Conv2d(64, 128, kernel_size=(1, 1), stride=(2, 2), bias=False)

(1): BatchNorm2d(128, eps=1e-05, momentum=0.1, affine=True, track_running_stats=True)

)

)

(1): BasicBlock(

(conv1): Conv2d(128, 128, kernel_size=(3, 3), stride=(1, 1), padding=(1, 1), bias=False)

(bn1): BatchNorm2d(128, eps=1e-05, momentum=0.1, affine=True, track_running_stats=True)

(relu): ReLU(inplace=True)

(conv2): Conv2d(128, 128, kernel_size=(3, 3), stride=(1, 1), padding=(1, 1), bias=False)

(bn2): BatchNorm2d(128, eps=1e-05, momentum=0.1, affine=True, track_running_stats=True)

)

)

(layer3): Sequential(

(0): BasicBlock(

(conv1): Conv2d(128, 256, kernel_size=(3, 3), stride=(2, 2), padding=(1, 1), bias=False)

(bn1): BatchNorm2d(256, eps=1e-05, momentum=0.1, affine=True, track_running_stats=True)

(relu): ReLU(inplace=True)

(conv2): Conv2d(256, 256, kernel_size=(3, 3), stride=(1, 1), padding=(1, 1), bias=False)

(bn2): BatchNorm2d(256, eps=1e-05, momentum=0.1, affine=True, track_running_stats=True)

(downsample): Sequential(

(0): Conv2d(128, 256, kernel_size=(1, 1), stride=(2, 2), bias=False)

(1): BatchNorm2d(256, eps=1e-05, momentum=0.1, affine=True, track_running_stats=True)

)

)

(1): BasicBlock(

(conv1): Conv2d(256, 256, kernel_size=(3, 3), stride=(1, 1), padding=(1, 1), bias=False)

(bn1): BatchNorm2d(256, eps=1e-05, momentum=0.1, affine=True, track_running_stats=True)

(relu): ReLU(inplace=True)

(conv2): Conv2d(256, 256, kernel_size=(3, 3), stride=(1, 1), padding=(1, 1), bias=False)

(bn2): BatchNorm2d(256, eps=1e-05, momentum=0.1, affine=True, track_running_stats=True)

)

)

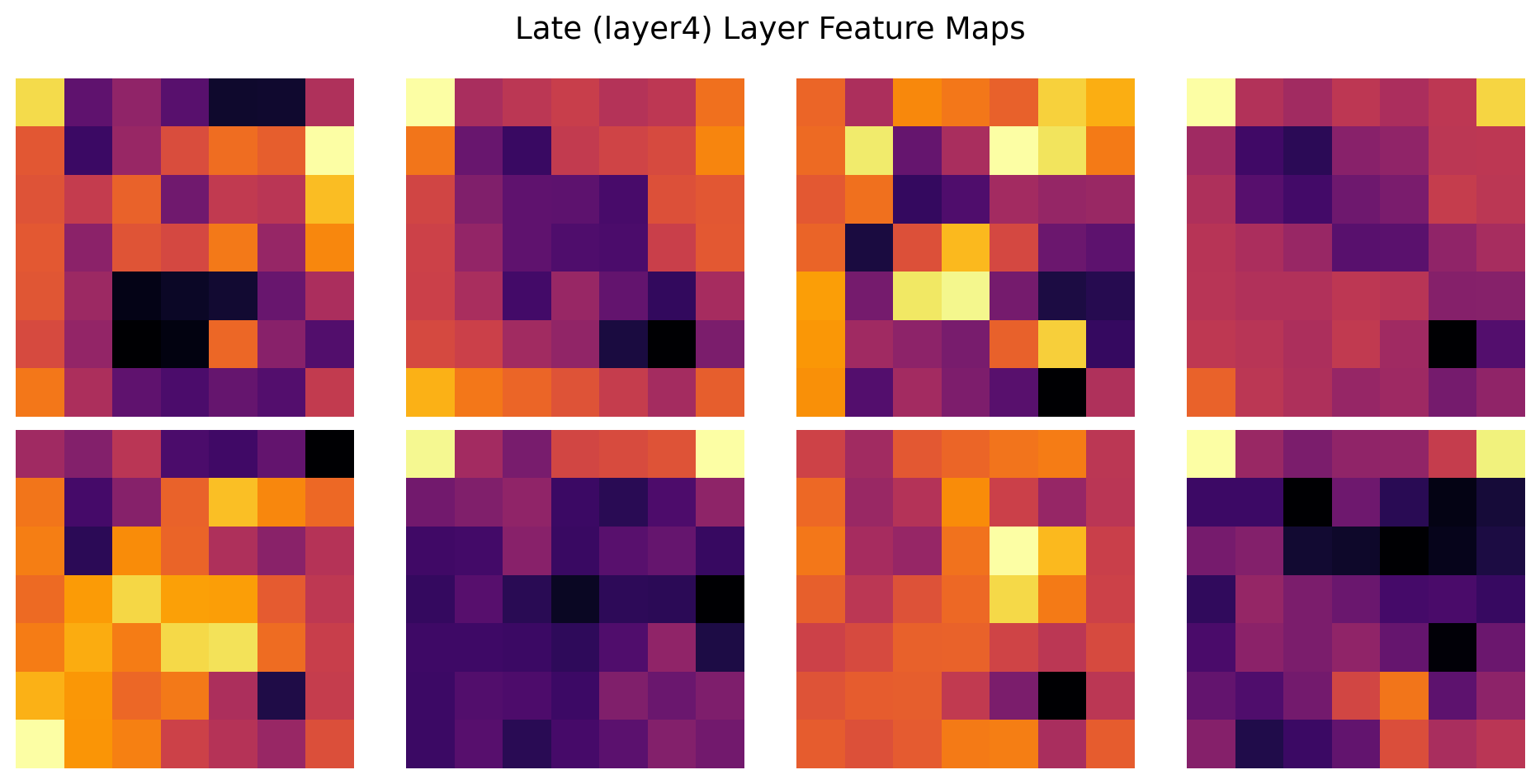

(layer4): Sequential(

(0): BasicBlock(

(conv1): Conv2d(256, 512, kernel_size=(3, 3), stride=(2, 2), padding=(1, 1), bias=False)

(bn1): BatchNorm2d(512, eps=1e-05, momentum=0.1, affine=True, track_running_stats=True)

(relu): ReLU(inplace=True)

(conv2): Conv2d(512, 512, kernel_size=(3, 3), stride=(1, 1), padding=(1, 1), bias=False)

(bn2): BatchNorm2d(512, eps=1e-05, momentum=0.1, affine=True, track_running_stats=True)

(downsample): Sequential(

(0): Conv2d(256, 512, kernel_size=(1, 1), stride=(2, 2), bias=False)

(1): BatchNorm2d(512, eps=1e-05, momentum=0.1, affine=True, track_running_stats=True)

)

)

(1): BasicBlock(

(conv1): Conv2d(512, 512, kernel_size=(3, 3), stride=(1, 1), padding=(1, 1), bias=False)

(bn1): BatchNorm2d(512, eps=1e-05, momentum=0.1, affine=True, track_running_stats=True)

(relu): ReLU(inplace=True)

(conv2): Conv2d(512, 512, kernel_size=(3, 3), stride=(1, 1), padding=(1, 1), bias=False)

(bn2): BatchNorm2d(512, eps=1e-05, momentum=0.1, affine=True, track_running_stats=True)

)

)

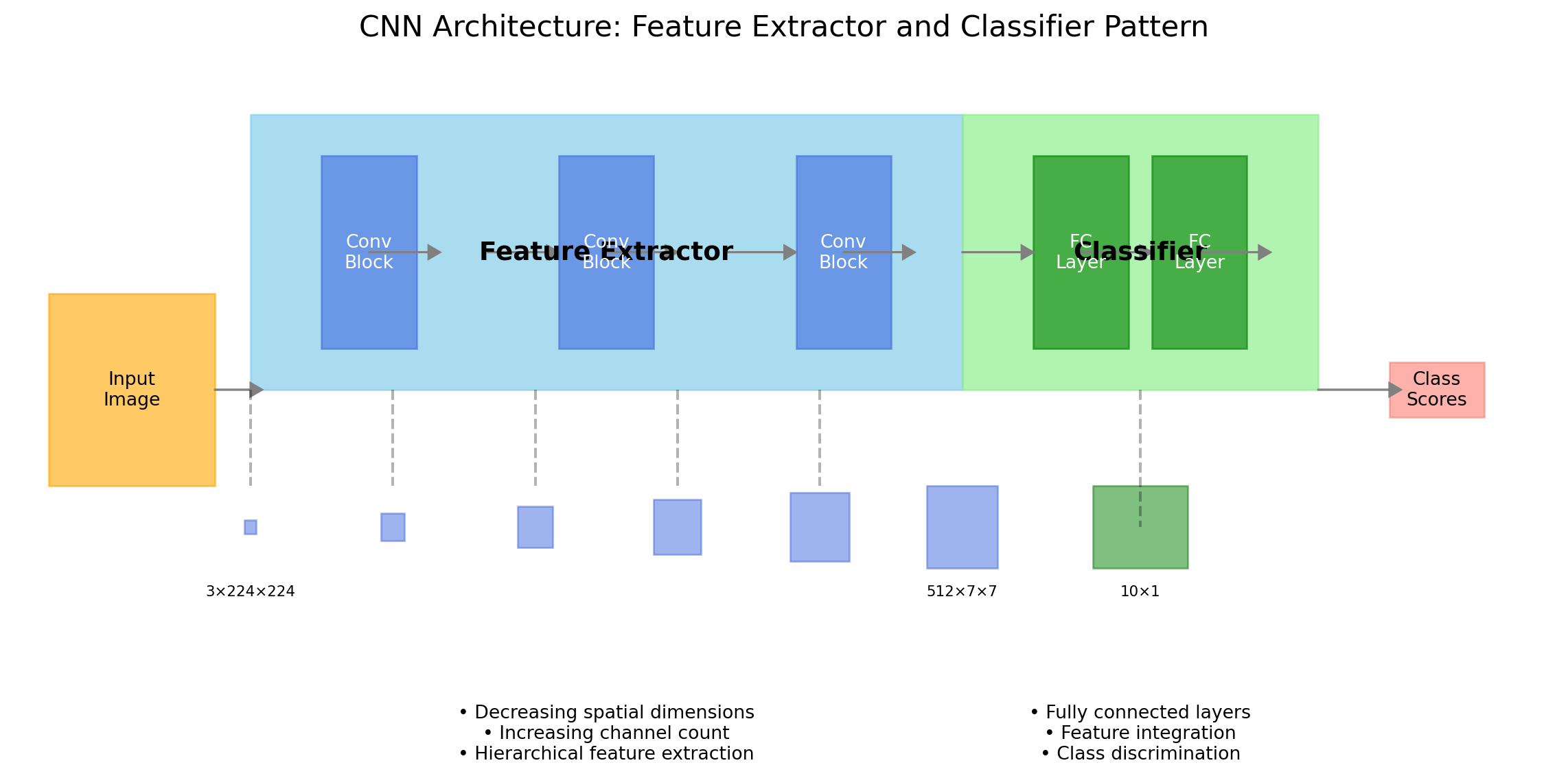

(avgpool): AdaptiveAvgPool2d(output_size=(1, 1))

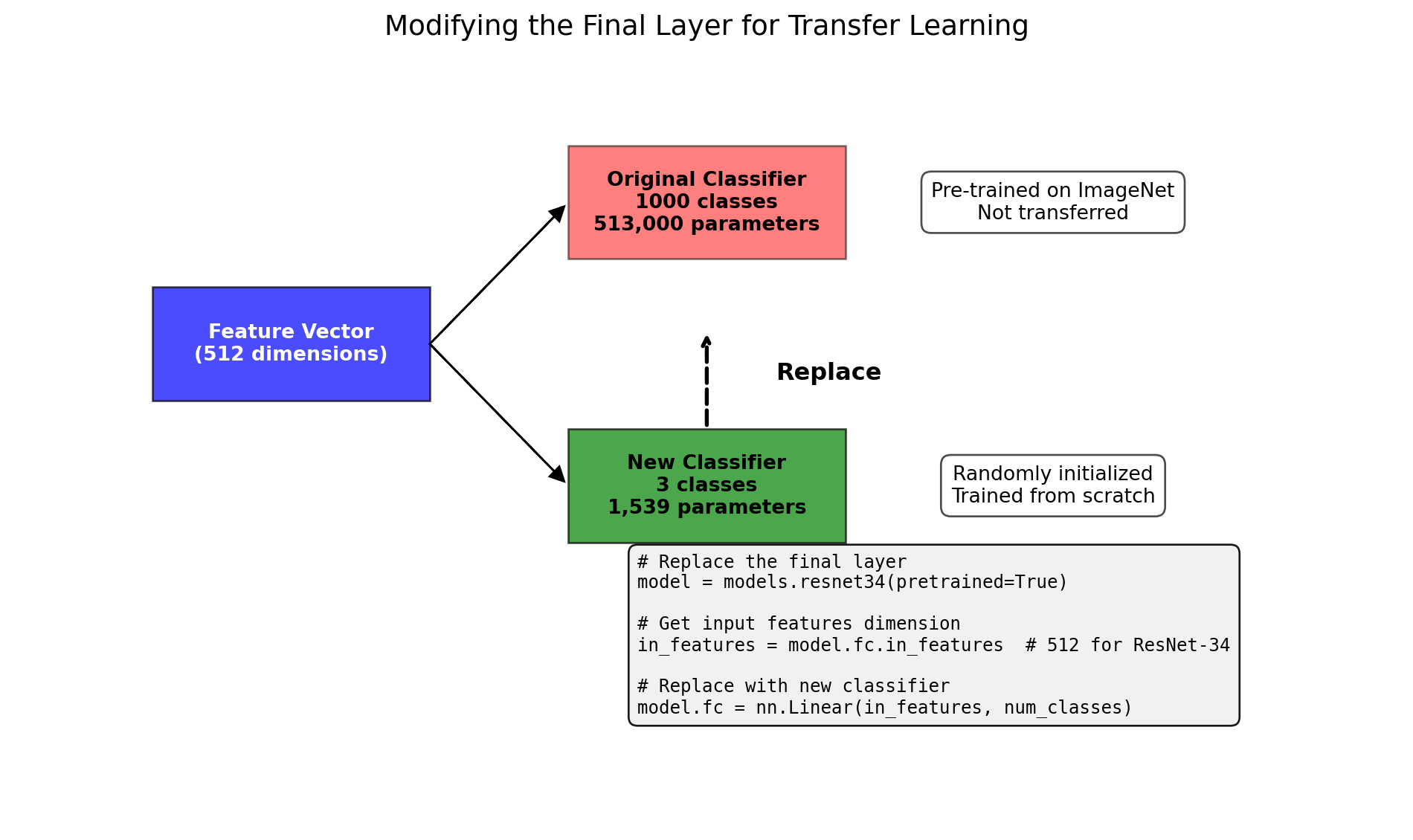

(fc): Linear(in_features=512, out_features=1000, bias=True)

)

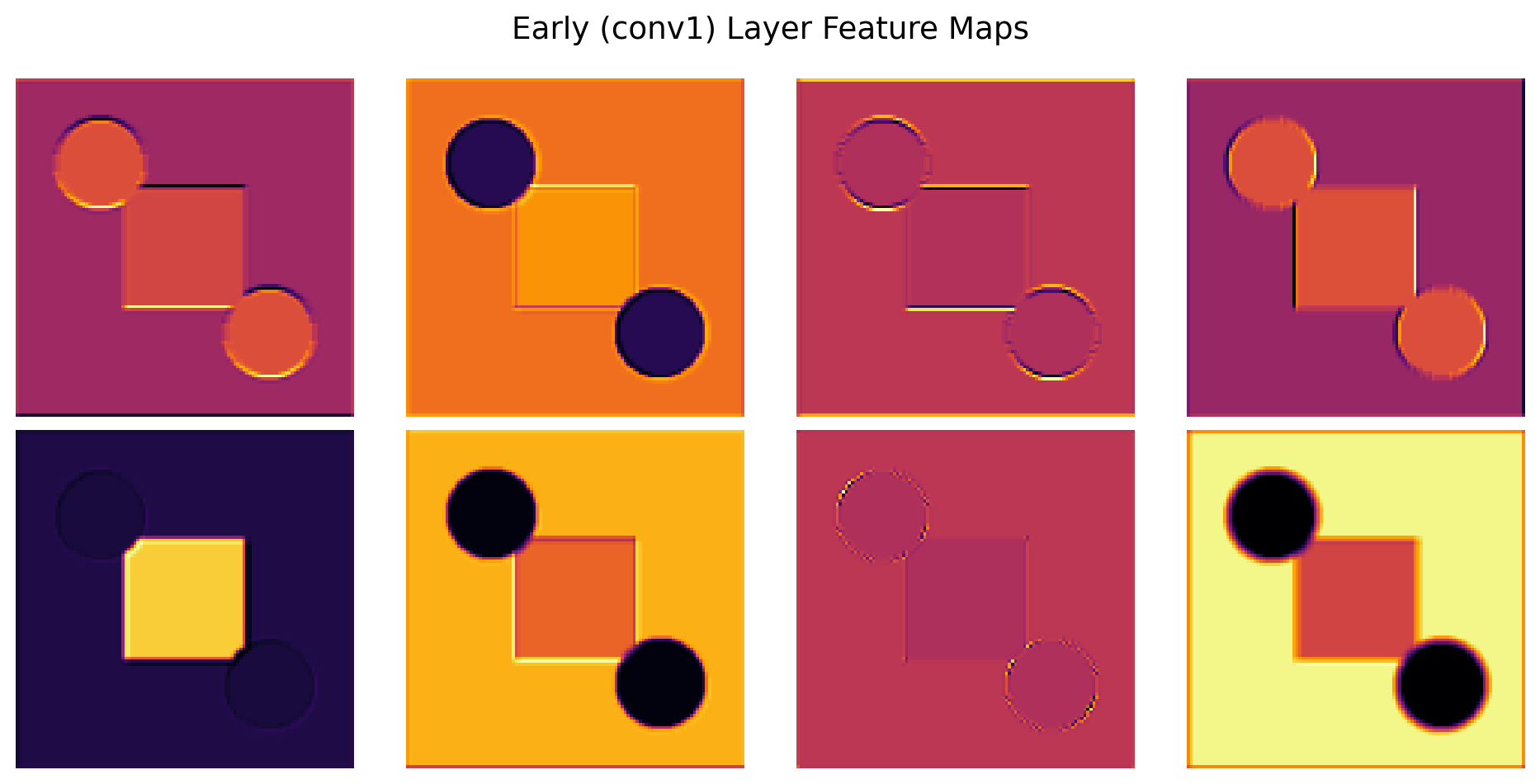

First Conv Layer Details:

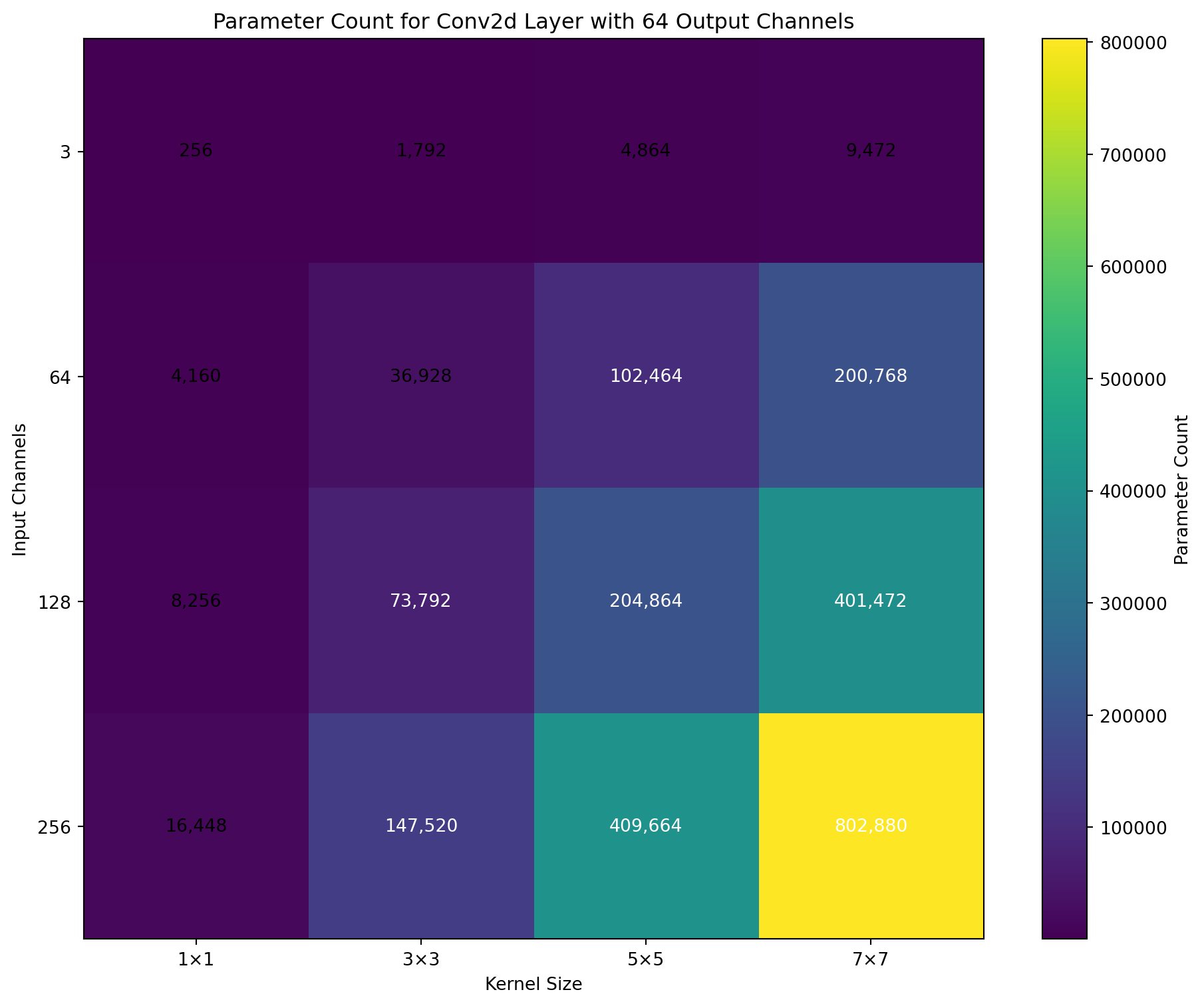

Type: <class 'torch.nn.modules.conv.Conv2d'>

Kernel size: (7, 7)

Stride: (2, 2)

Padding: (3, 3)

Input channels: 3

Output channels: 64

Parameter count: 9408

Input shape: torch.Size([1, 3, 224, 224])

Output shape: torch.Size([1, 64, 112, 112])