Computational Deep Learning

EE 541 - Unit 1

Spring 2026

Deep Learning

How Neural Networks Learn

Learning to Classify

What is Machine Learning?

Learning = Task + Performance Measure + Experience

Herbert Simon (1983)

“Learning is any process by which a system improves performance from experience.”

Framework

\[\text{Learning System} = (\mathcal{T}, \mathcal{P}, \mathcal{E})\]

- Task \(\mathcal{T}\): What to accomplish

- Performance \(\mathcal{P}\): How to measure success

- Experience \(\mathcal{E}\): Data to learn from

Learning occurs when: \[\mathcal{P}_{\text{after}}(\mathcal{T}, \mathcal{E}) > \mathcal{P}_{\text{before}}(\mathcal{T})\]

Example: Email Spam Filter

- Task (\(\mathcal{T}\)): Classify emails as spam/not spam

- Performance (\(\mathcal{P}\)): % correctly classified

- Experience (\(\mathcal{E}\)): Database of labeled emails

Example: Self-Driving Car

- \(\mathcal{T}\): Navigate roads safely

- \(\mathcal{P}\): Miles without intervention

- \(\mathcal{E}\): Hours of human driving data

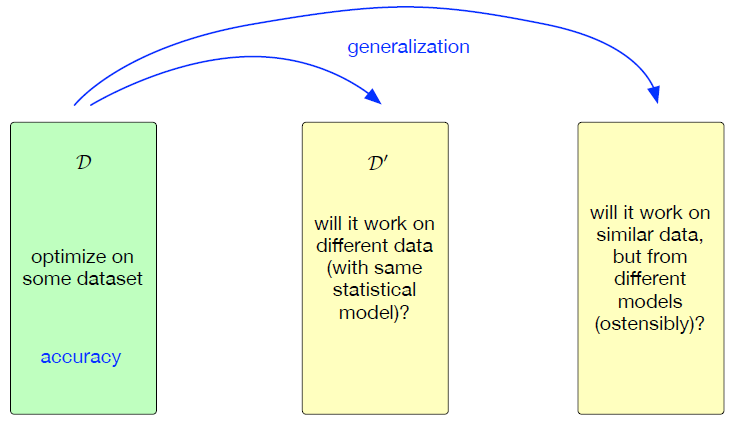

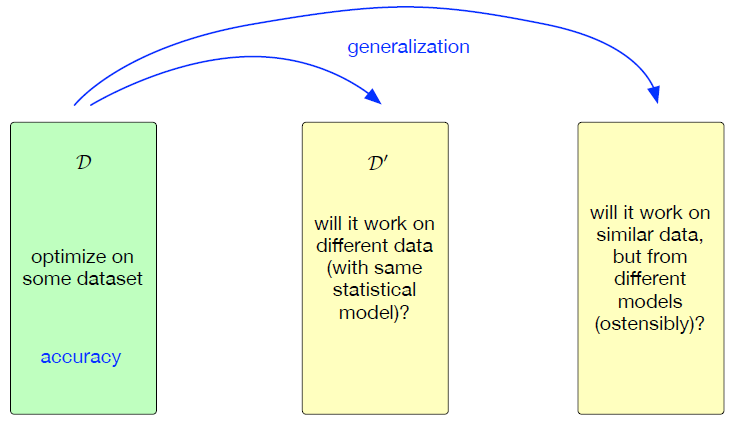

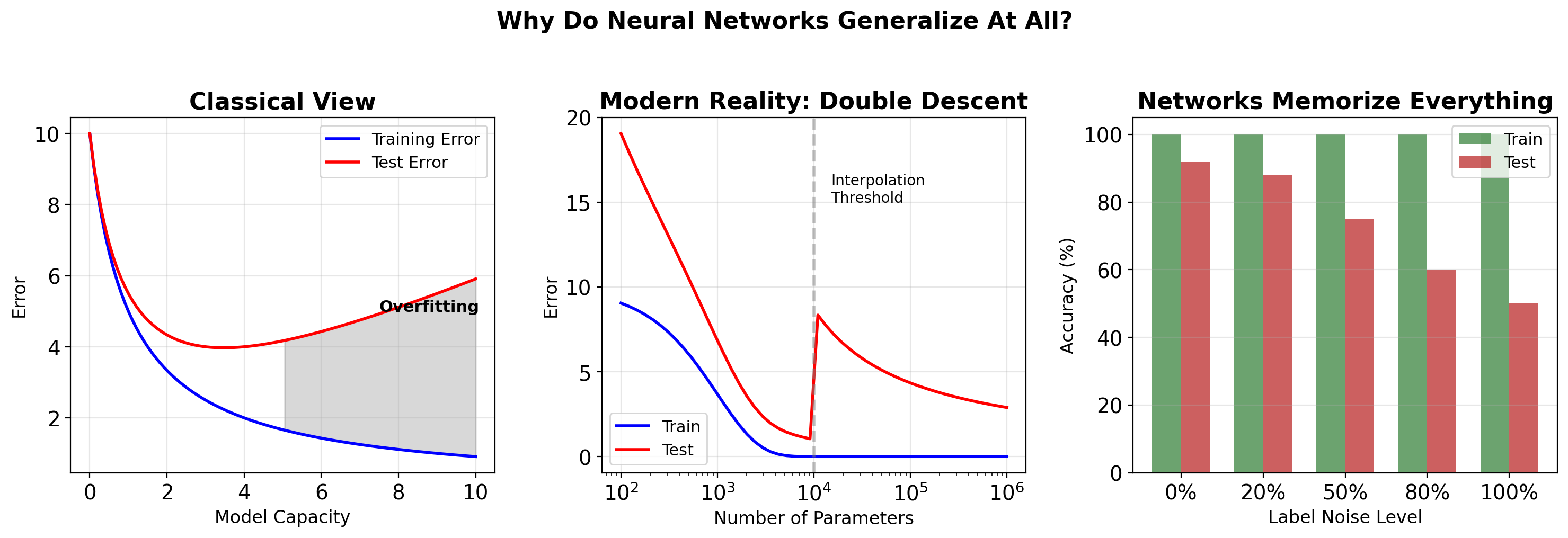

Generalization is the Goal of Machine Learning

- Do not care about performance on the dataset we have

- Do care about performance on similar data that has no labels

- Accuracy/Generalization trade-off (bias-variance trade):

- Optimizing accuracy to the extreme reduces capability to generalize

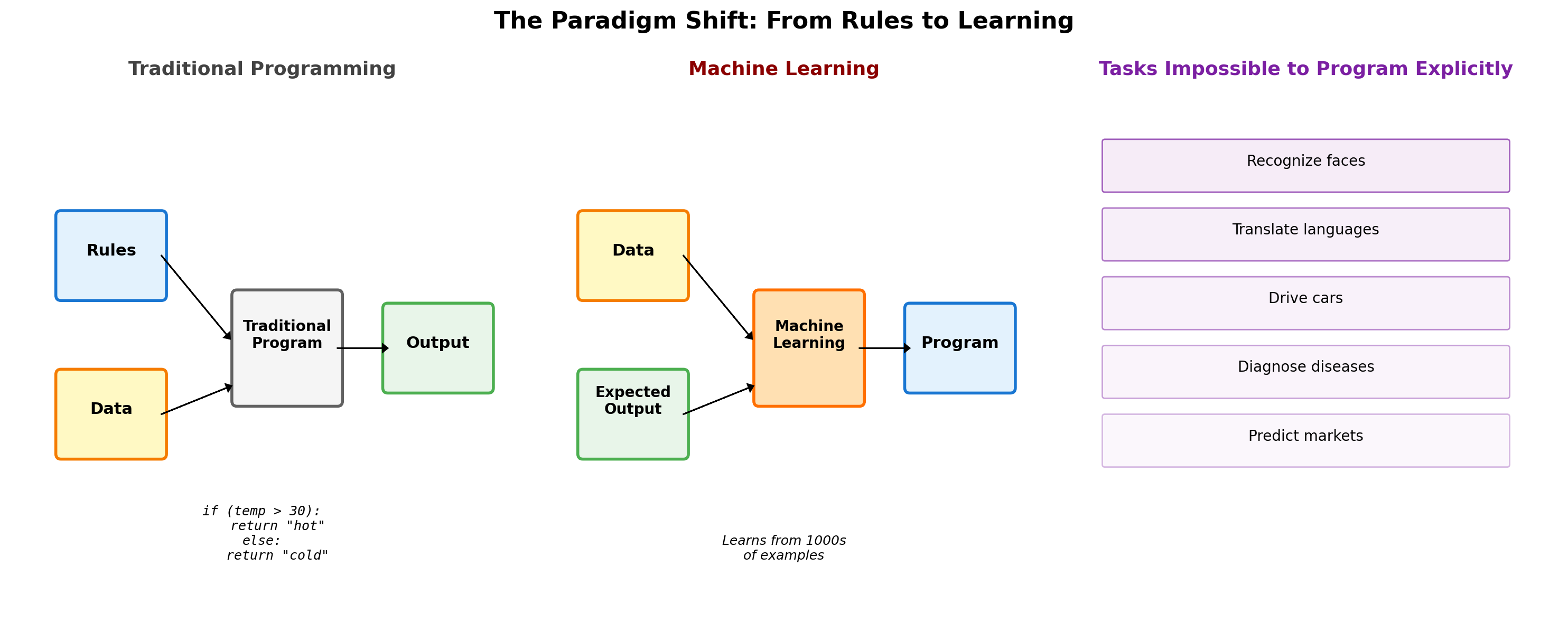

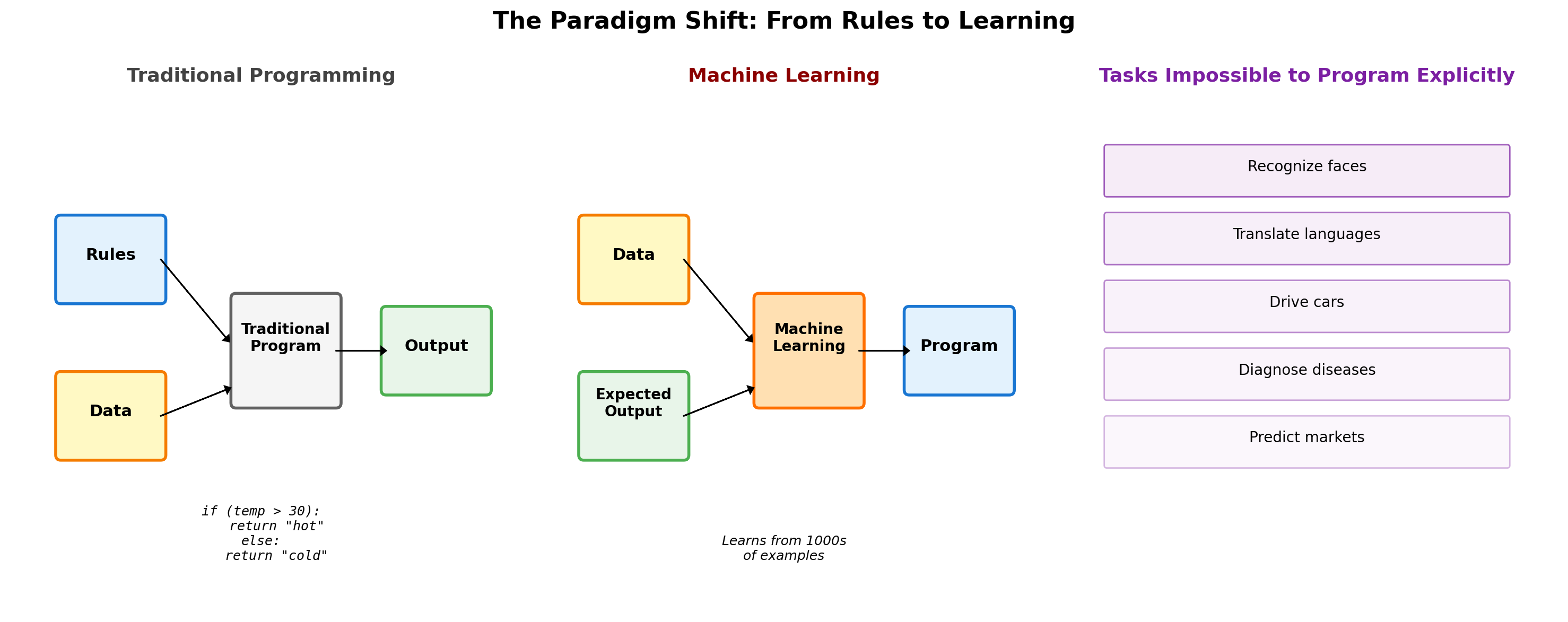

Machine Learning Inverts Traditional Programming

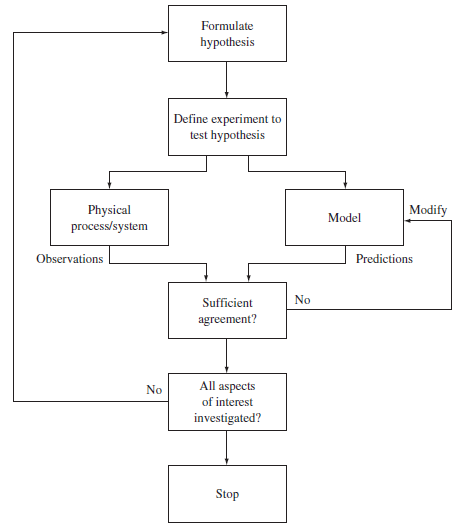

Theory-Driven vs Data-Driven Approaches

Classical: Theory-Driven

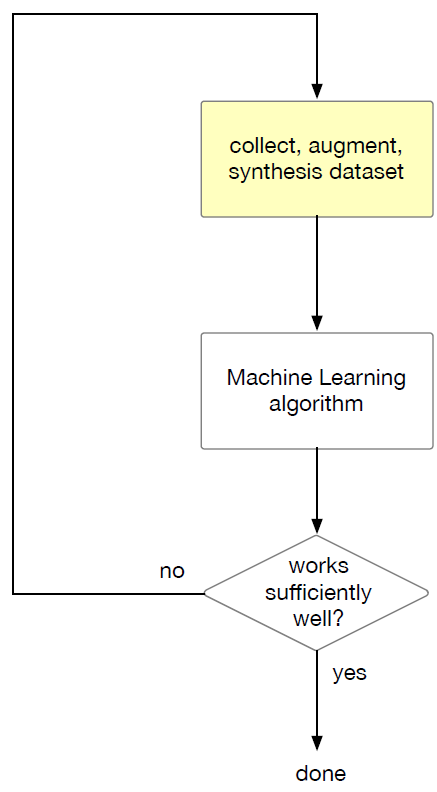

Modern: Data-Driven

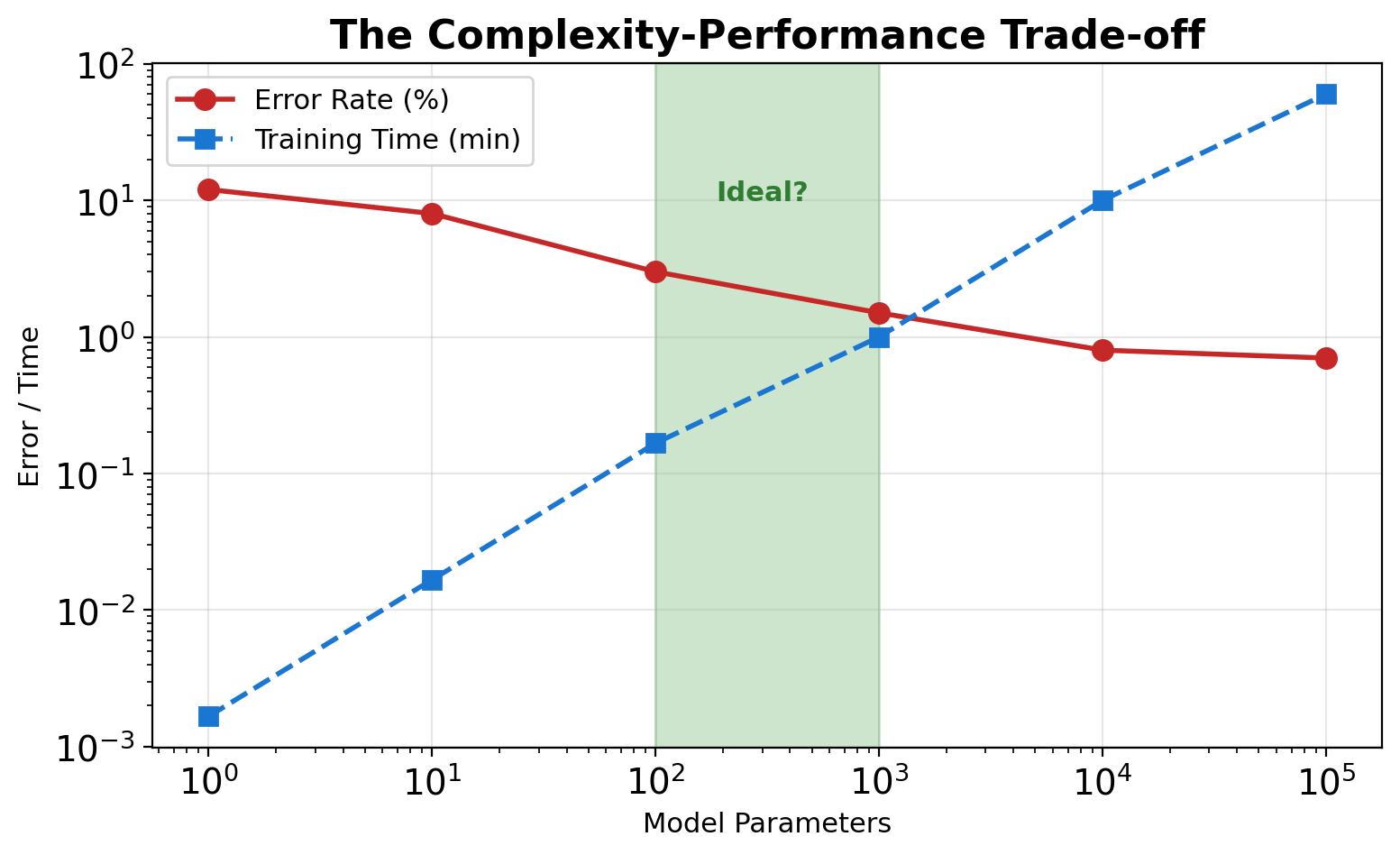

Model Complexity: When to Stop Adding Parameters

George Box (1976)

“All models are wrong, but some are useful”

“Since all models are wrong the scientist cannot obtain a ‘correct’ one by excessive elaboration”

Box’s warning: More parameters ≠ better science

MNIST Classification: Accuracy vs Complexity

- Nearest neighbor: 3% error, \(\mathcal{O}(n)\) inference

- Linear classifier: 8% error, \(\mathcal{O}(d)\) inference

- 2-layer network: 2% error, 50K parameters

- ConvNet (LeNet-5): 0.8% error, 60K parameters

- ResNet-50: 0.2% error, 25M parameters

Question: Is 0.2% → 0.1% worth 25M parameters?

Worrying Selectively

It is inappropriate to be concerned about mice when there are tigers abroad

- Start simple

- Add complexity purposefully

- Validate empirically

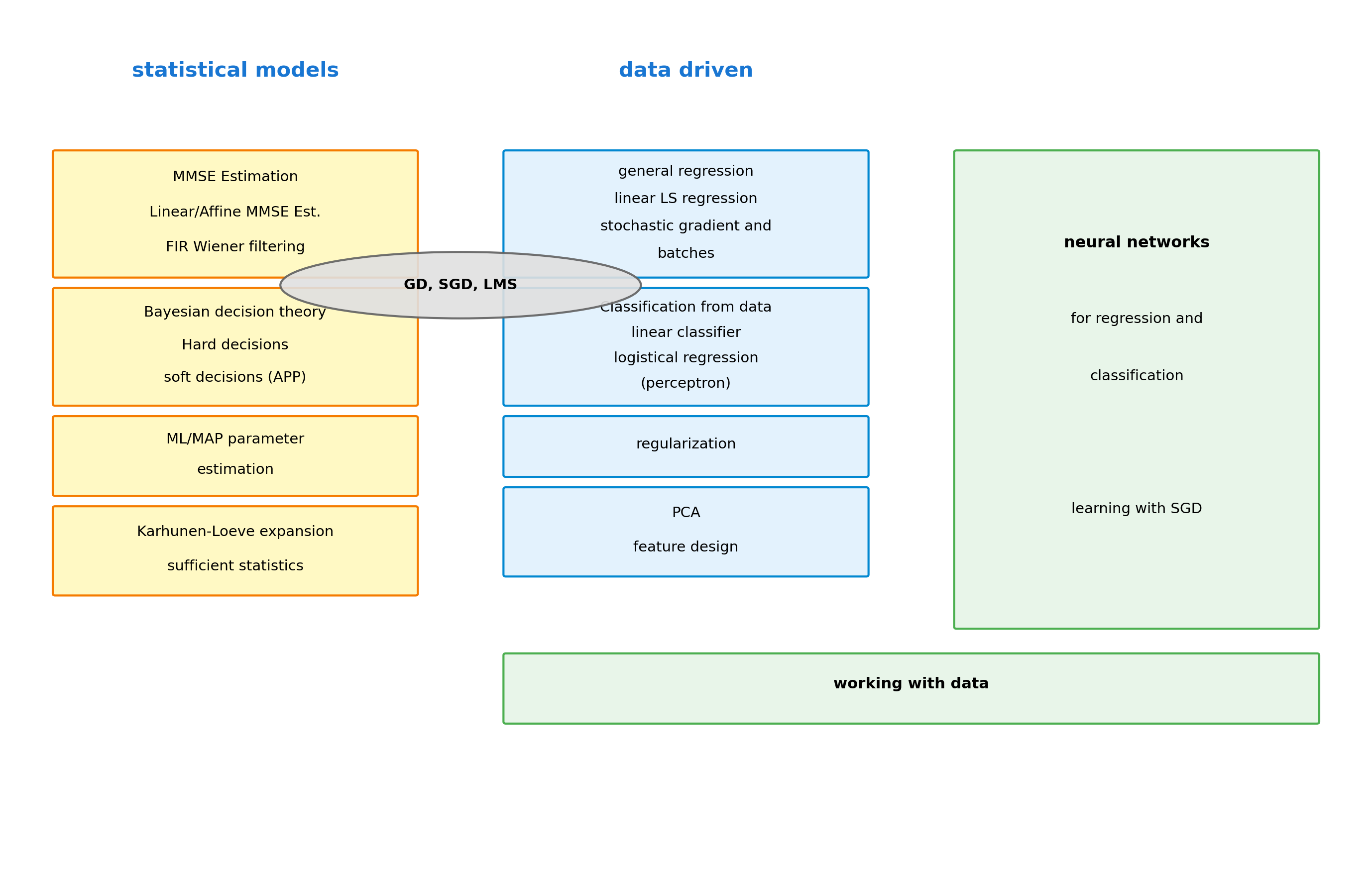

Course Structure: Statistical Foundations to Neural Networks

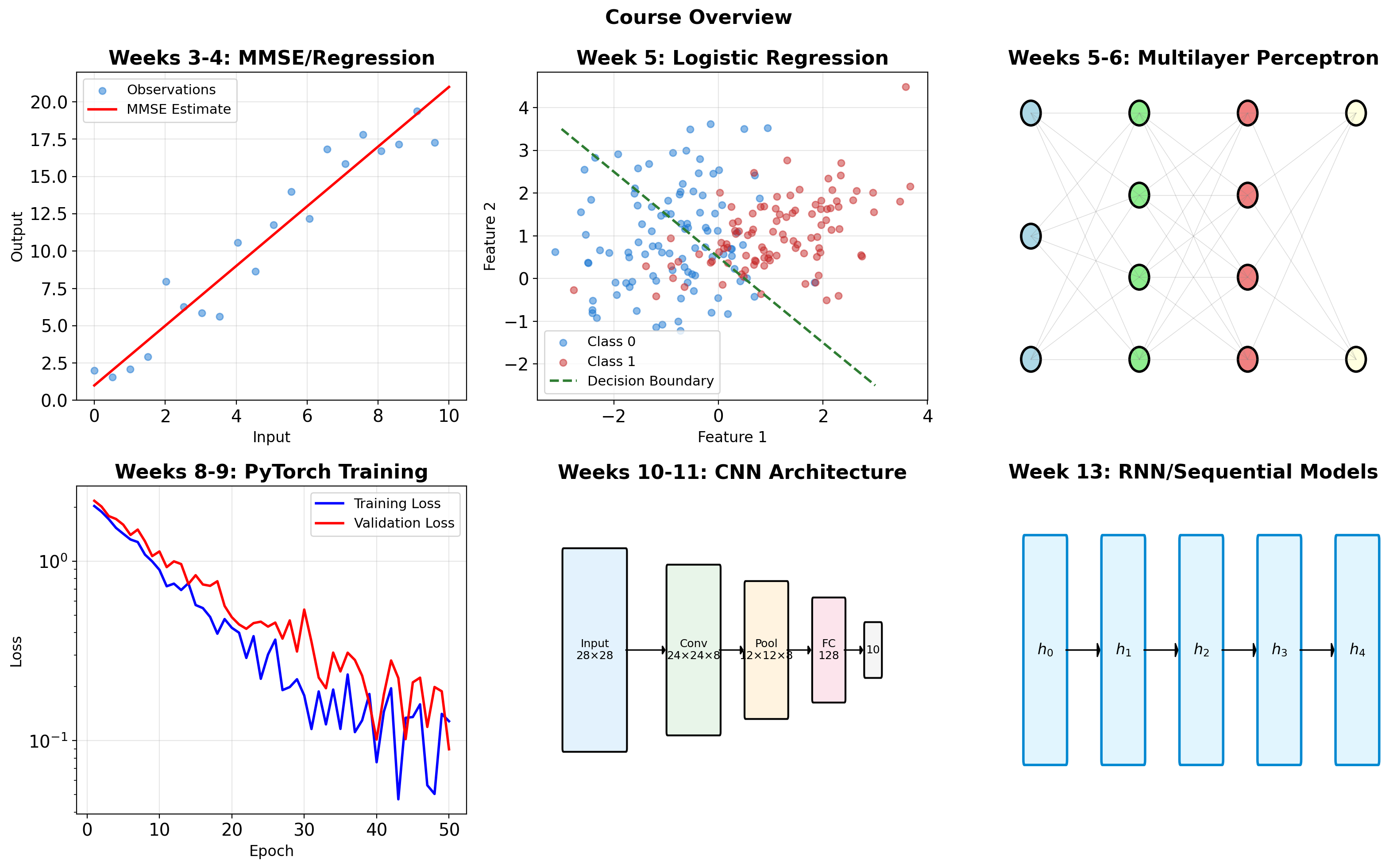

Semester Progression: MMSE to Convolutional Networks

Outline

Foundations

- Task, performance, experience

- Generalization as the goal

- Linear models and their limits

- Bias-variance tradeoff

- Quality vs quantity

- Representation and dimensionality

- Supervised, unsupervised, reinforcement

- Self-supervised methods

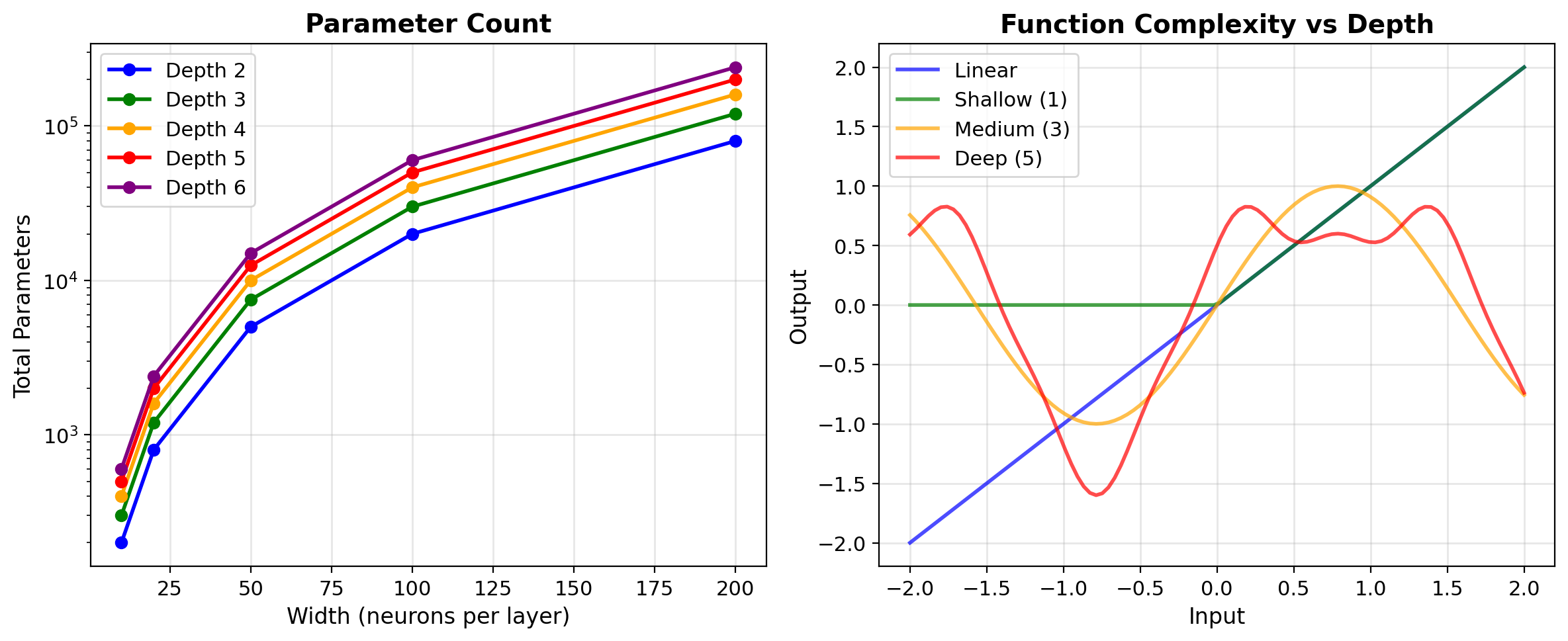

Neural Networks

- Perceptron to deep networks

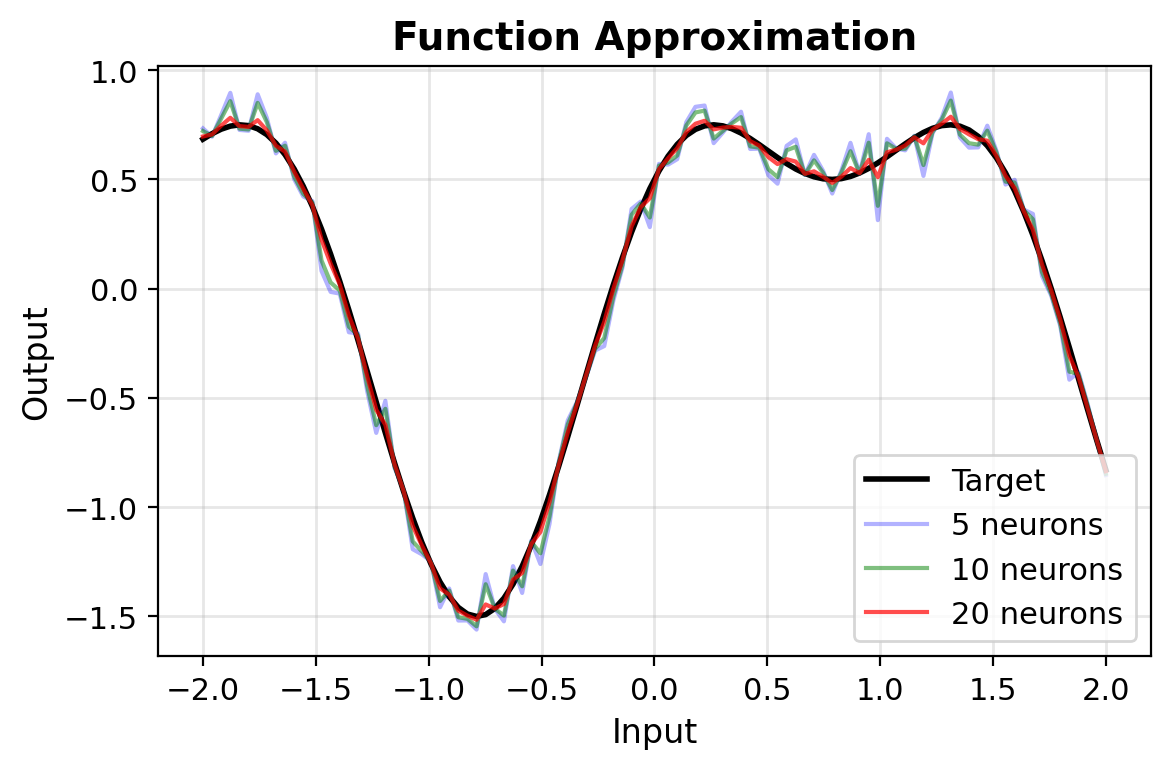

- Universal approximation

- Width vs depth

- Loss landscapes

- SGD and variants

- The mystery of why networks work

Practice

- Fashion-MNIST classifier

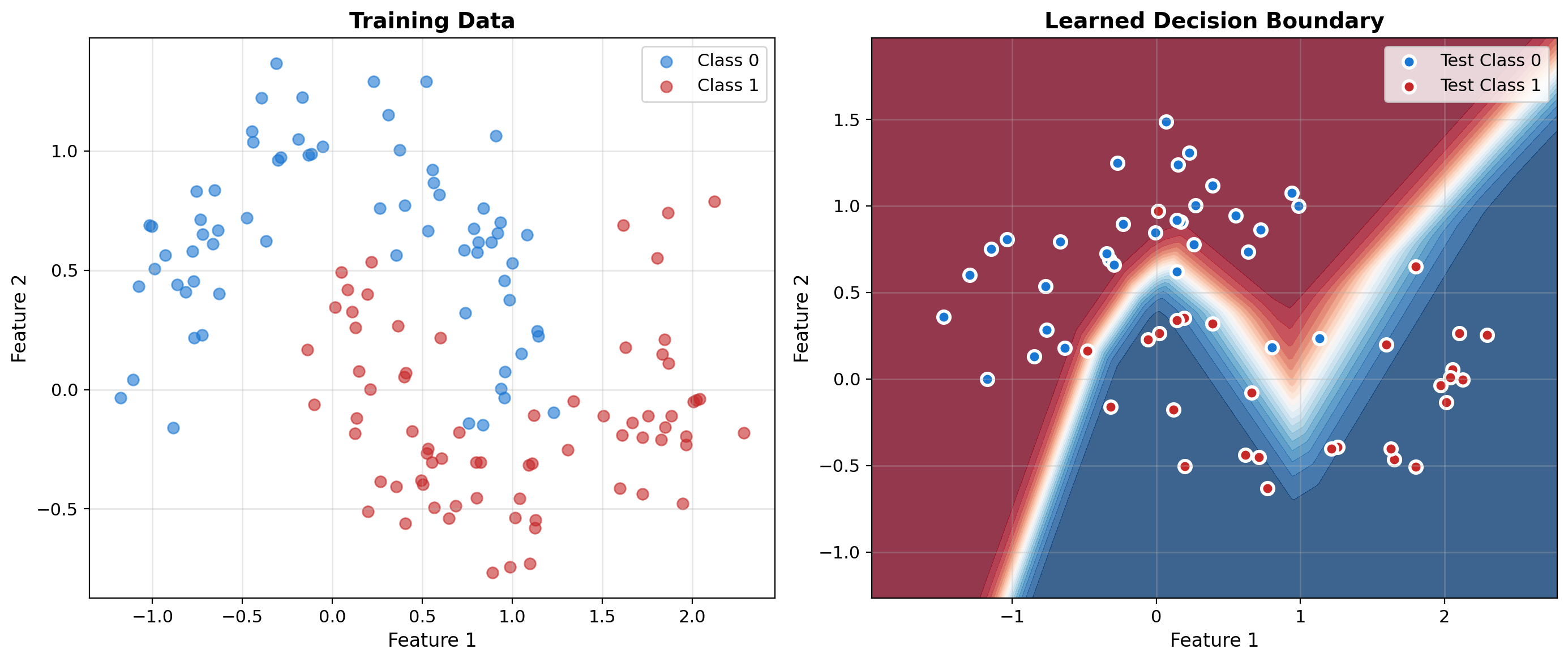

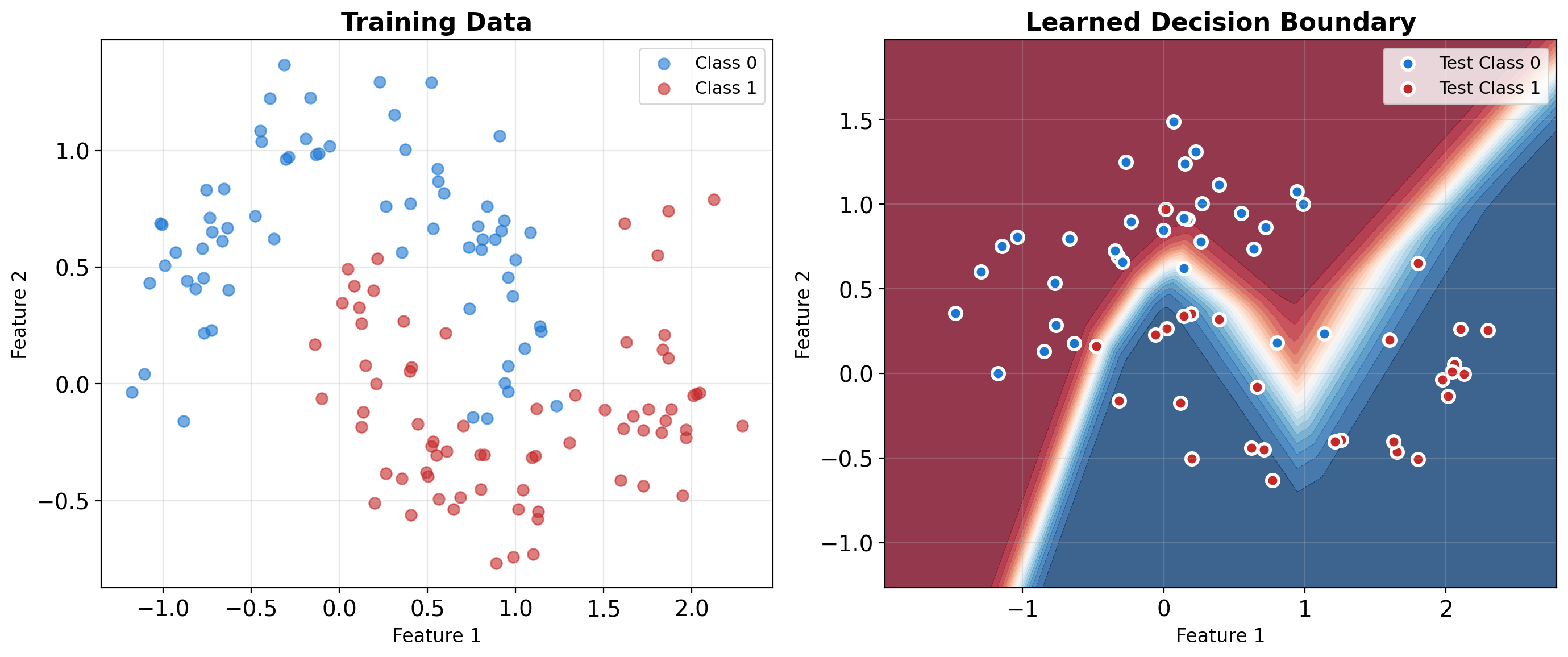

Linear Models Fail on Nonlinear Boundaries

Two-Moons Dataset

Tests whether a model can learn curved decision boundaries. Two interleaving half-circles that cannot be separated by any straight line.

Neural Networks Learn Nonlinear Decision Boundaries

Code

import numpy as np

from sklearn.neural_network import MLPClassifier

from sklearn.datasets import make_moons

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

X, y = make_moons(n_samples=200, noise=0.2, random_state=42)

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(

X, y, test_size=0.3, random_state=42

)

mlp = MLPClassifier(

hidden_layer_sizes=(10, 10),

max_iter=1000,

random_state=42

)

mlp.fit(X_train, y_train)

print(f"Training accuracy: {mlp.score(X_train, y_train):.3f}")

print(f"Test accuracy: {mlp.score(X_test, y_test):.3f}")Training accuracy: 0.979

Test accuracy: 0.950

Learning Fundamentals

Minimize Expected Risk Using Only Finite Samples

Given

- Training data: \(\mathcal{D} = \{(\mathbf{x}_i, y_i)\}_{i=1}^N\)

- Hypothesis class: \(\mathcal{H}\)

- Loss function: \(\mathcal{L}\)

Goal

Find \(h^* \in \mathcal{H}\) that minimizes:

\[\mathbb{E}_{(\mathbf{x},y) \sim P}[\mathcal{L}(h(\mathbf{x}), y)]\]

But we only have access to:

\[\frac{1}{N}\sum_{i=1}^N \mathcal{L}(h(\mathbf{x}_i), y_i)\]

Generalization Gap

Minimize error on unseen data using only observed samples

This gap defines machine learning

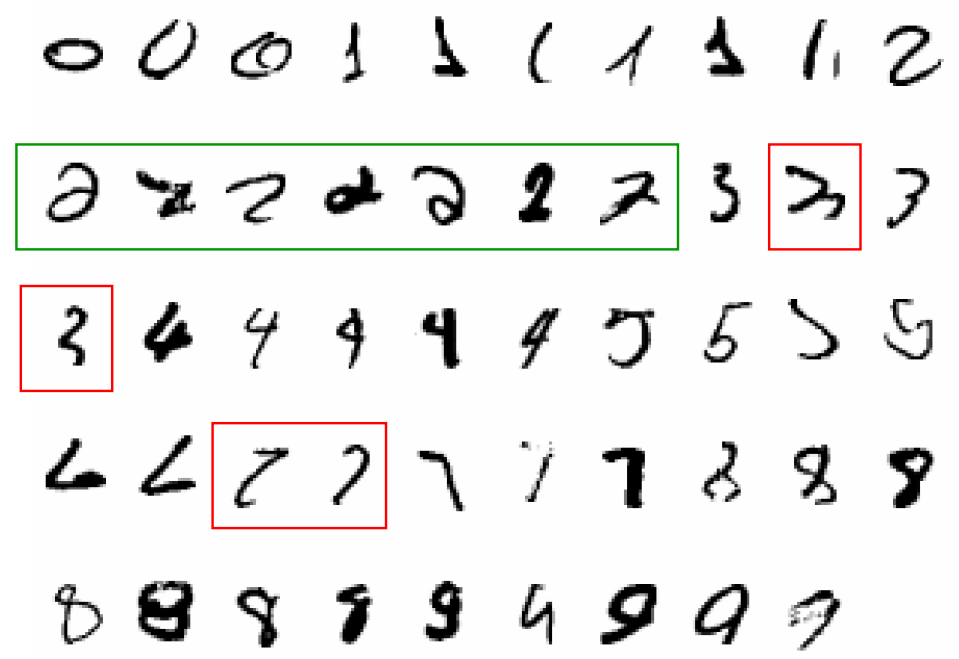

Example Task: “2s” Detector

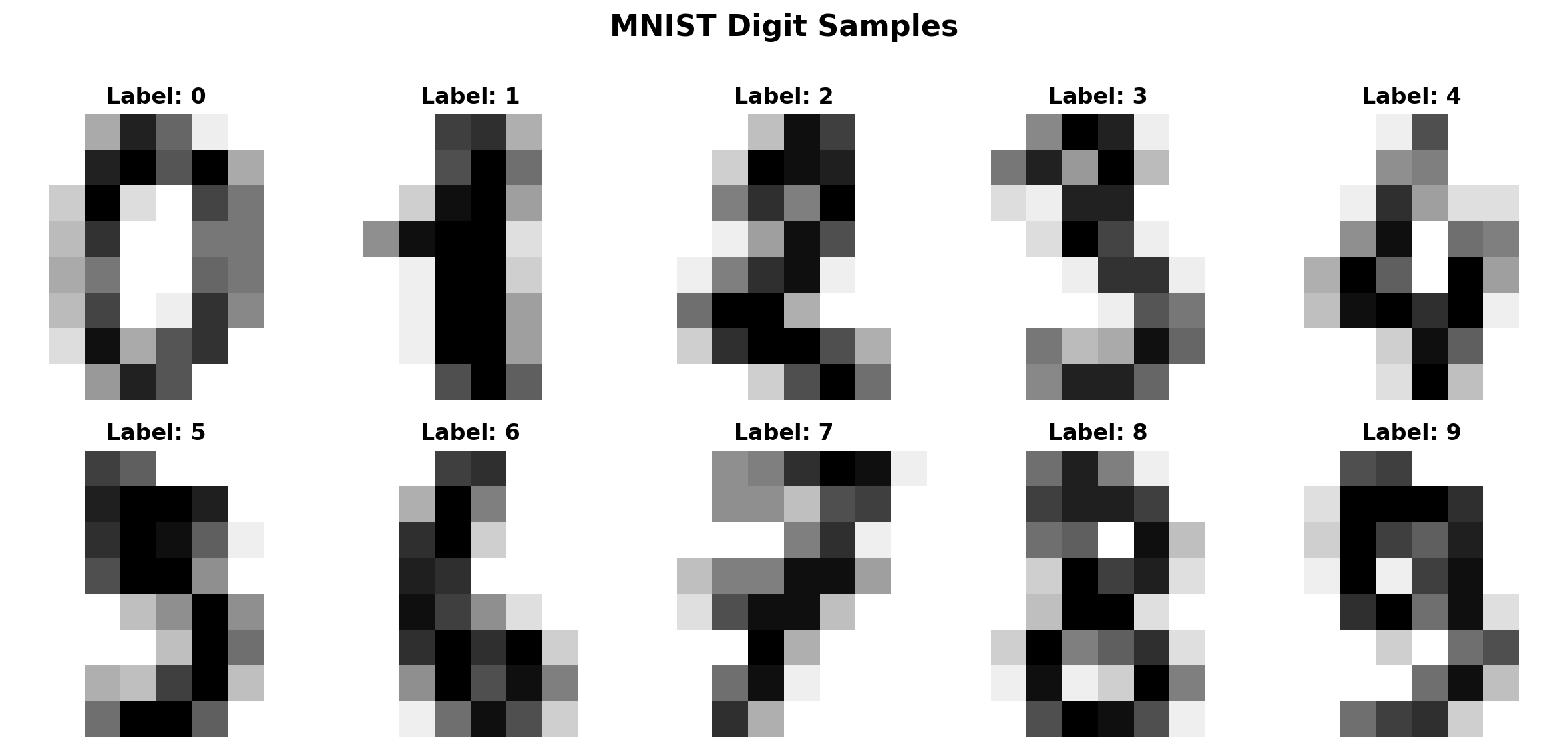

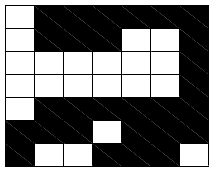

MNIST: Input and Output Representations

Input Space

- Raw pixels: \(\mathbf{x} \in \{0,255\}^{784}\)

- Normalized: \(\mathbf{x} \in [0,1]^{784}\)

- Binary: \(\mathbf{x} \in \{0,1\}^{784}\)

Output Space

- Classification: \(y \in \{0,1,...,9\}\)

- One-hot: \(\mathbf{y} \in \{0,1\}^{10}\)

- Probability: \(\mathbf{y} \in [0,1]^{10}\)

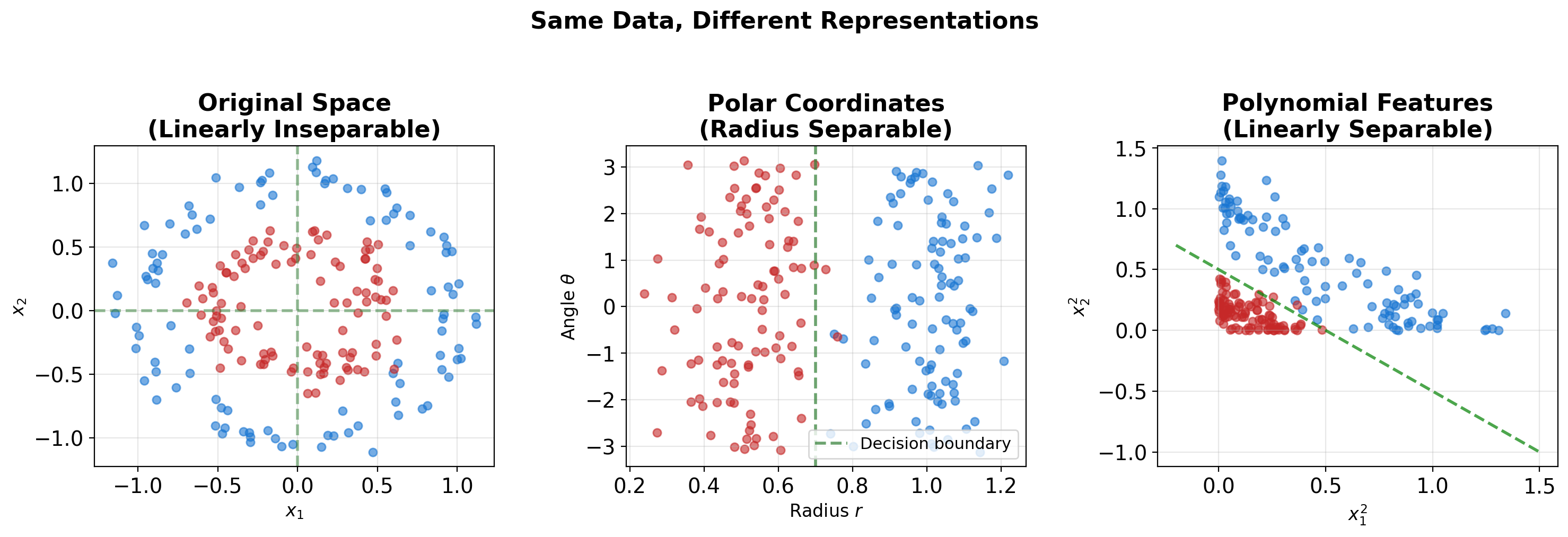

Same Data, Multiple Representations

Representation Determines Learnability

The choice of representation can make learning tractable or impossible. Deep learning learns representations automatically.

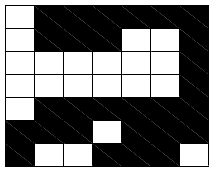

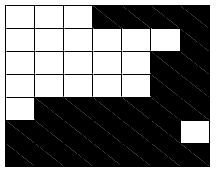

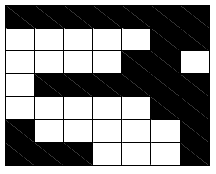

Example: The Data Domain

GOOD

GOOD

BAD

?

The choice of how to represent input is very important

Can we classify the unknown pattern?

Converting Pattern to Binary Vector

Binary Representation

x = 0111111011100100000010000

001011111111101111001110Label: “GOOD”

Key Insight

The same pattern can be represented as:

- Raw pixels

- Binary vectors (length d = 49)

- Feature vectors

- Learned representations

A hypothesis class can succeed or fail based on the choice of representation.

Linear Classifier on Binary Representation

Representation: Binary vectors, length \(d = 49\)

\[\mathbf{x} = \begin{bmatrix} 0111111011100100000010000 \\ 001011111111101111001110 \end{bmatrix}\]

\[y \in \{-1, +1\}\]

Hypothesize mapping data to label using linear classifier:

\[\hat{y} = \text{sign}(\mathbf{w} \cdot \mathbf{x}) = \text{sign}(w_1 x_1 + \cdots + w_{49} x_{49})\]

Definition: Linear Function

A function \(f: \mathbb{R}^d \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) is linear if \(f(\mathbf{x}) = \mathbf{w}^\top \mathbf{x} + b\) for some \(\mathbf{w} \in \mathbb{R}^d\) and \(b \in \mathbb{R}\). The decision boundary \(\{\mathbf{x} : f(\mathbf{x}) = 0\}\) is a hyperplane.

where:

- \(\mathbf{w}\): Parameters to learn (weight vector)

- \(\hat{y}\): Predicted label (sign of linear combination)

Linear vs Nonlinear Hypothesis Classes

\[\mathcal{H}_{\text{linear}}: h(\mathbf{x}) = \text{sign}(\mathbf{w}^T\mathbf{x} + b)\] \[\mathcal{H}_{\text{neural}}: h(\mathbf{x}) = h_2(\mathbf{W}_2 \cdot h_1(\mathbf{W}_1\mathbf{x} + \mathbf{b}_1) + \mathbf{b}_2)\]

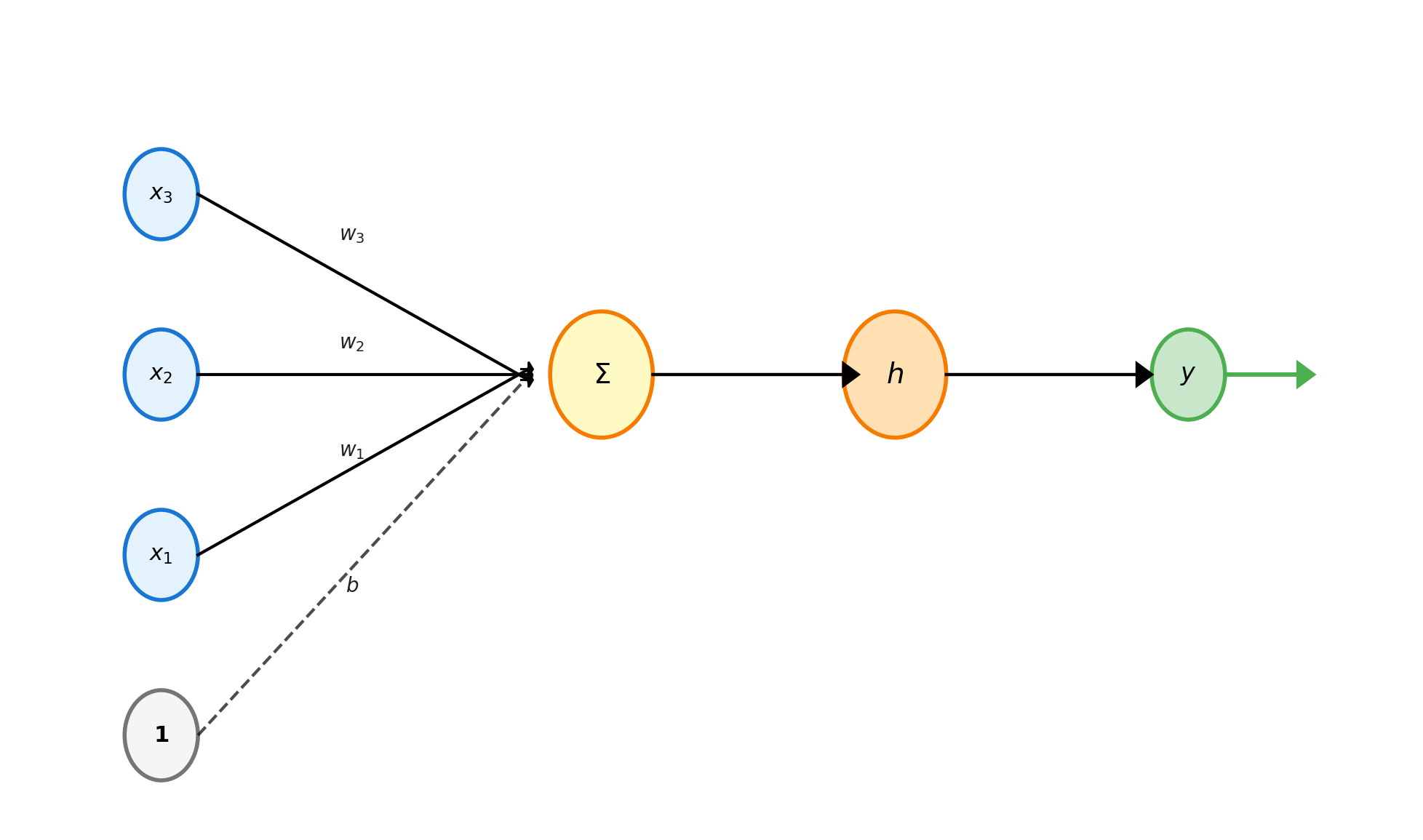

Perceptron: Linear Combination + Nonlinearity

Mathematical Model

\[y = h\left(\sum_{i=1}^n w_i x_i + b\right) = h(\mathbf{w}^T\mathbf{x} + b)\]

where \(h\) is an activation function:

- Step: \(h(z) = \begin{cases} 1 & z \geq 0 \\ 0 & z < 0 \end{cases}\)

- Sigmoid: \(h(z) = \frac{1}{1 + e^{-z}}\)

- ReLU: \(h(z) = \max(0, z)\)

Activation Functions Add Nonlinearity

Why Nonlinearity Matters

Without activation functions, stacking layers is pointless: \(f(\mathbf{W}_2 \mathbf{W}_1 \mathbf{x}) = f(\mathbf{W} \mathbf{x})\) where \(\mathbf{W} = \mathbf{W}_2\mathbf{W}_1\)

Later topic: Gradient flow and vanishing gradients during backpropagation

Closed-Form vs Iterative Optimization

Explicit (Closed-form)

\[\mathbf{w}^* = \arg\min_{\mathbf{w}} \|\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{X}\mathbf{w}\|^2\]

Solution: \[\mathbf{w}^* = (\mathbf{X}^T\mathbf{X})^{-1}\mathbf{X}^T\mathbf{y}\]

- One-shot computation

- Requires matrix inversion

- Memory intensive for large data

Iterative (Gradient-based)

\[\mathbf{w}_{t+1} = \mathbf{w}_t - \eta \nabla_{\mathbf{w}}\mathcal{L}(\mathbf{w}_t)\]

- Sequential updates

- Scales to large datasets

- Foundation of deep learning

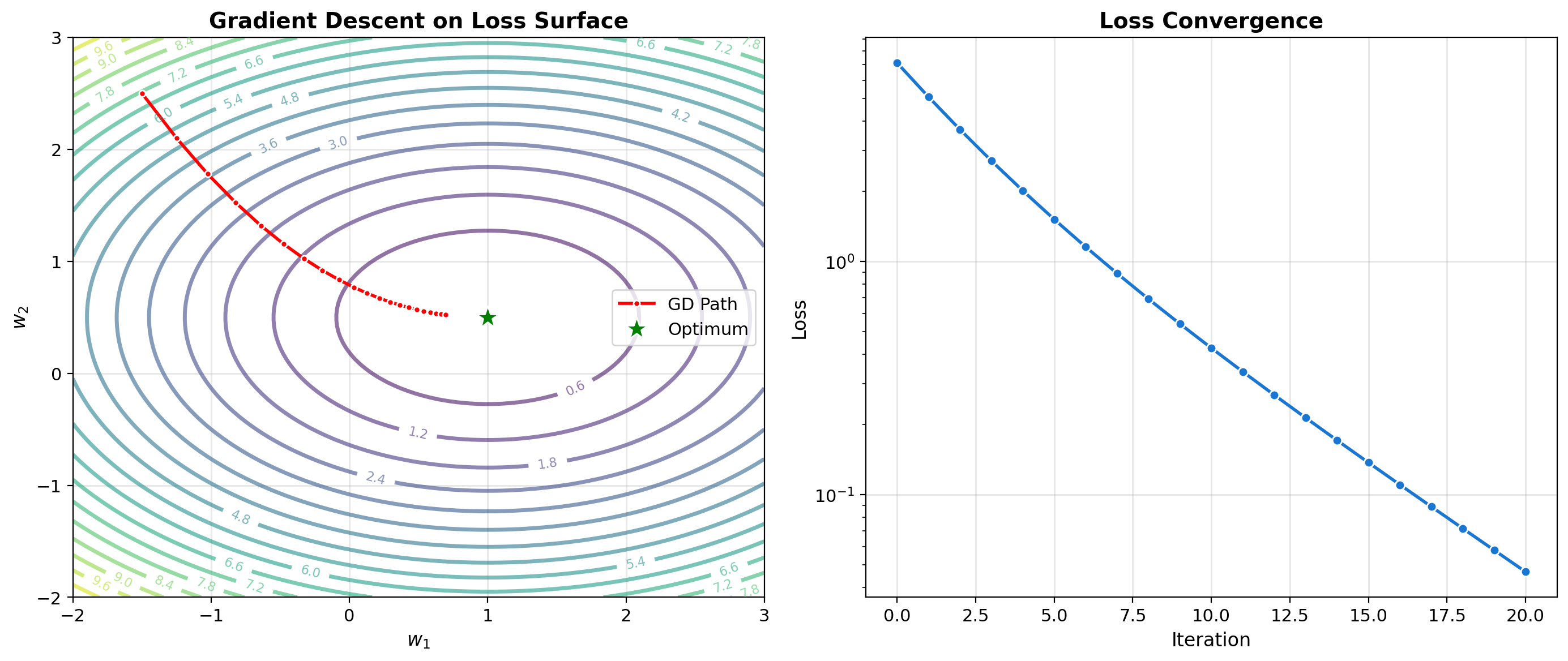

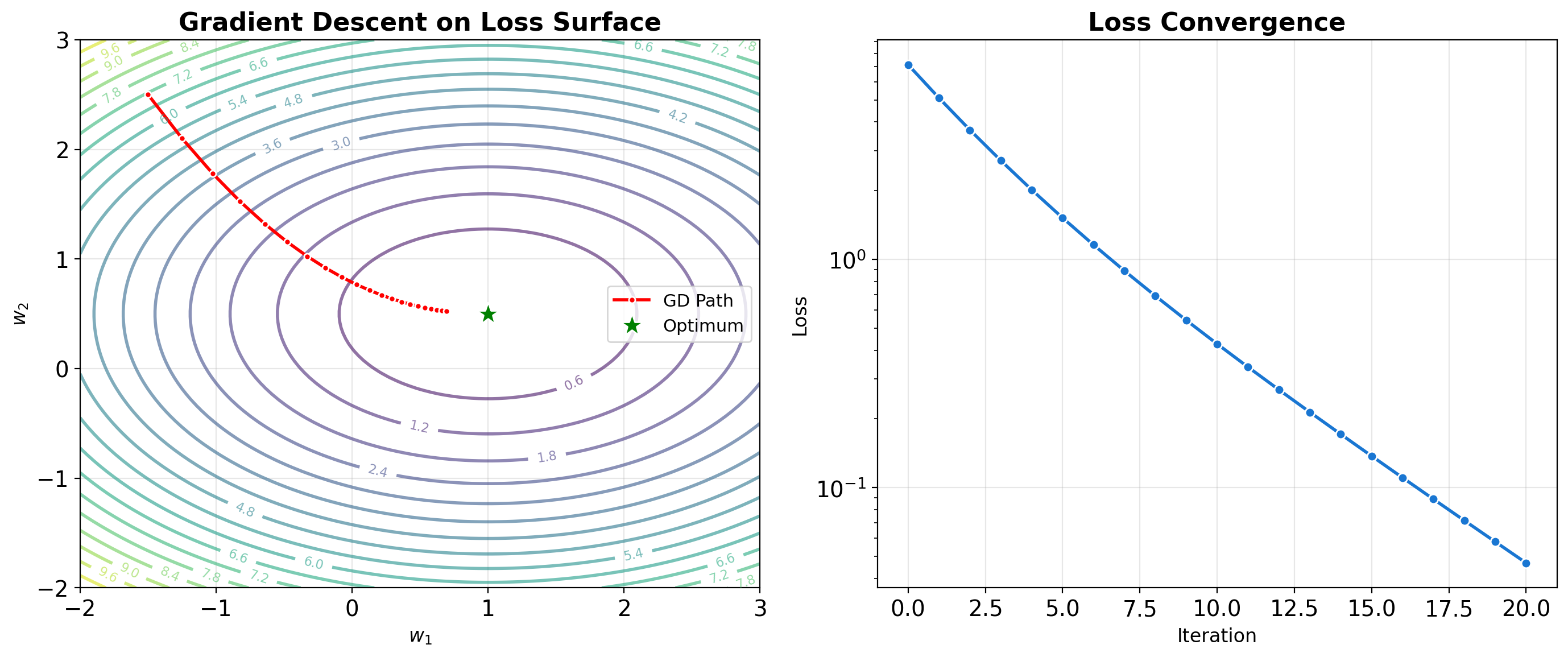

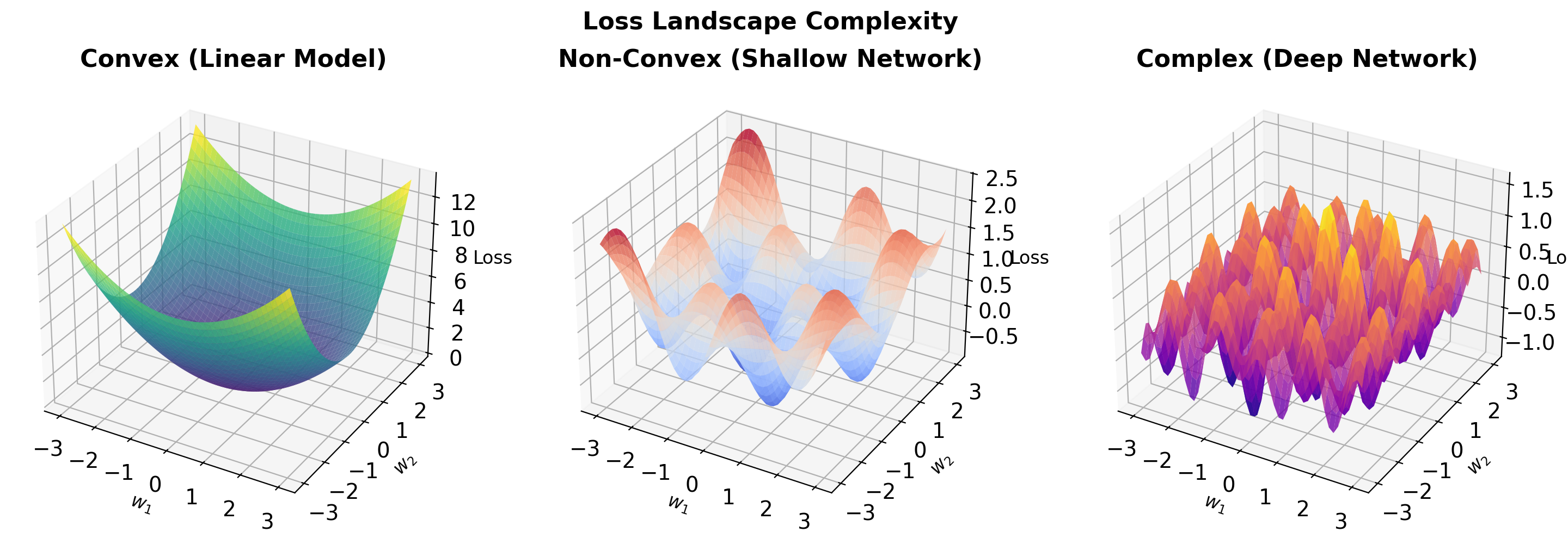

Gradient Descent Visualization

Iterative Optimization Principle

Gradient descent navigates the loss landscape by repeatedly moving in the direction of steepest descent. For convex problems, this guarantees convergence to the global minimum. For neural networks, we settle for local minima that generalize well.

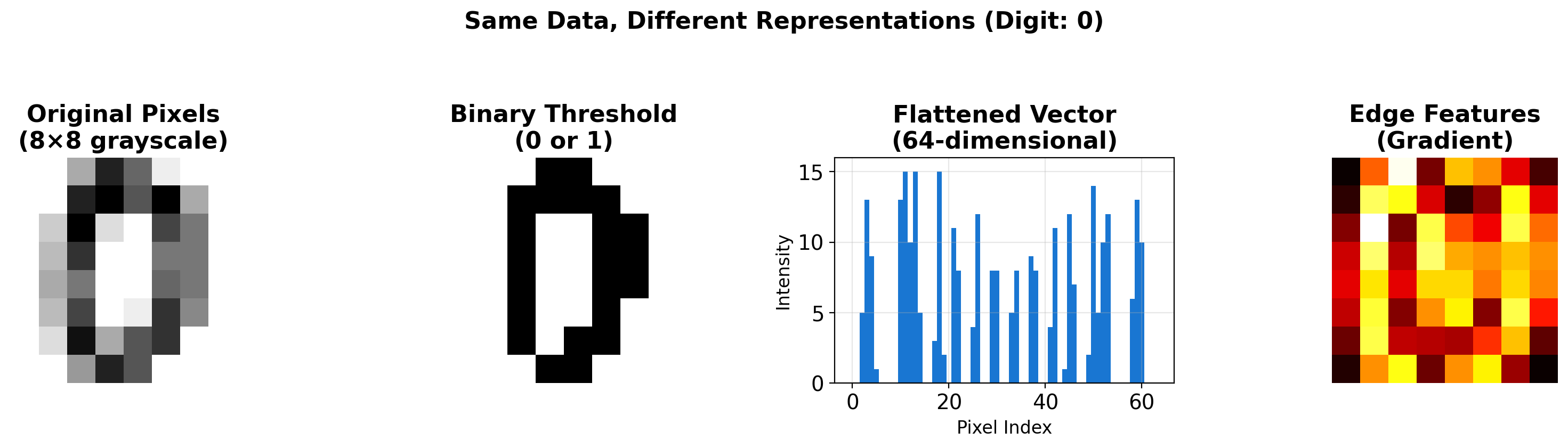

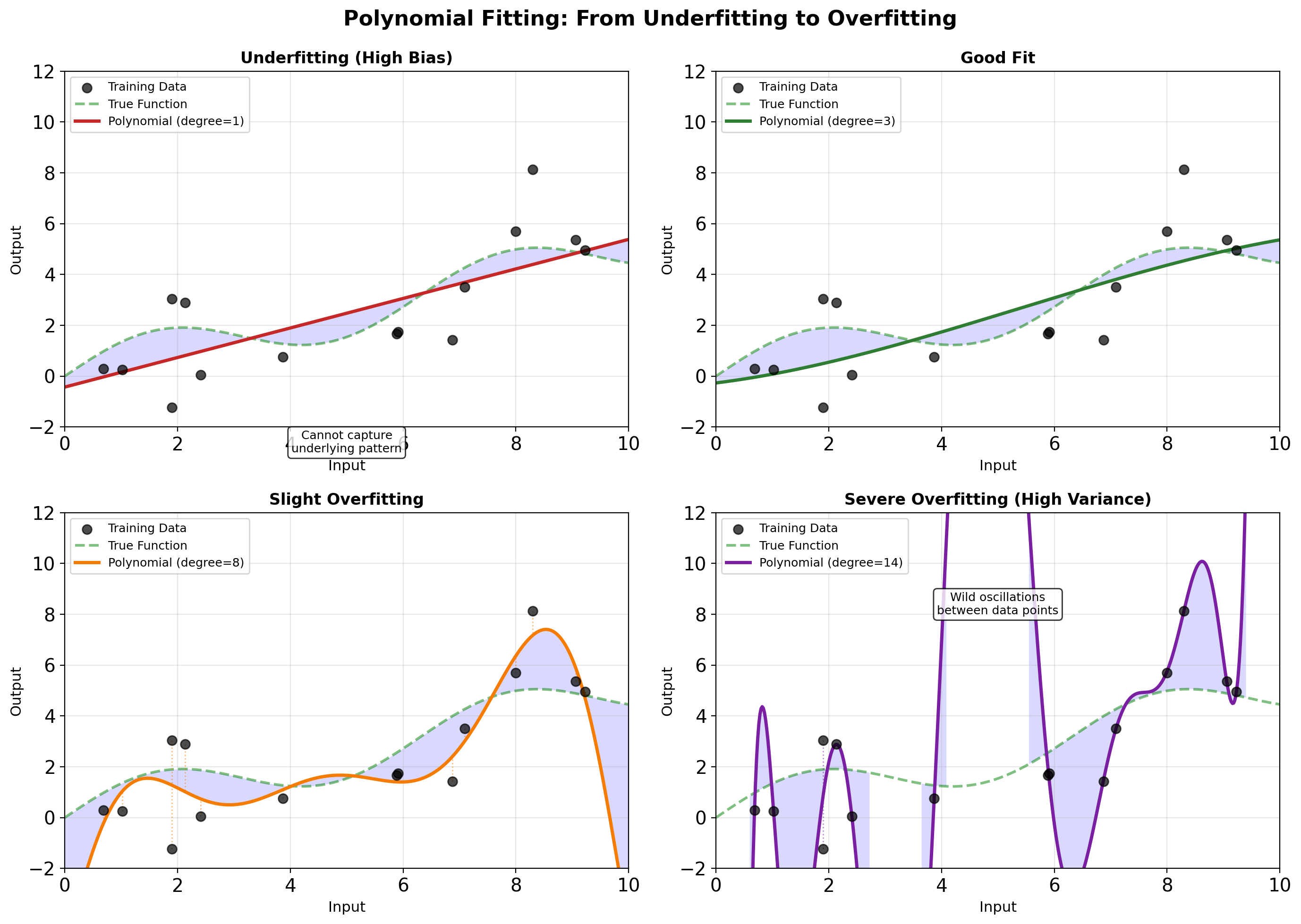

The Bias-Variance Decomposition

Expected Prediction Error

\[\text{MSE} = \text{Bias}^2 + \text{Variance} + \sigma^2\]

Bias: Error from wrong model assumptions

- High bias: Model too simple (underfits)

- Low bias: Model captures true pattern

Variance: Error from sensitivity to training data

- High variance: Model memorizes noise (overfits)

- Low variance: Model finds generalizable pattern

Irreducible error (\(\sigma^2\)): Noise inherent in data

Tradeoff: Complex models reduce bias but increase variance

Bias-Variance in Practice: Polynomial Fitting

- Degree 1: Too simple, systematic error (high bias)

- Degree 3: Captures pattern without noise

- Degree 8: Starts fitting noise

- Degree 14: Wild oscillations (high variance)

Increasing complexity: bias decreases, variance increases

EE 541 Core Principles

Theory

Learning = Function Approximation

- From data to predictions

- Hypothesis class defines possibilities

Representation Matters

- Same data, different encodings

- Deep learning learns representations

Generalization is the Goal

- Not memorization

- Balance complexity with data

Implementation

- Start Simple

- Linear models as baselines

- Add complexity purposefully

- Iterate and Validate

- Gradient descent scales

- Monitor train vs test error

- EE 541 Progression

- MMSE → Regression → Neural Nets

- Theory + PyTorch implementation

Listen to the Data

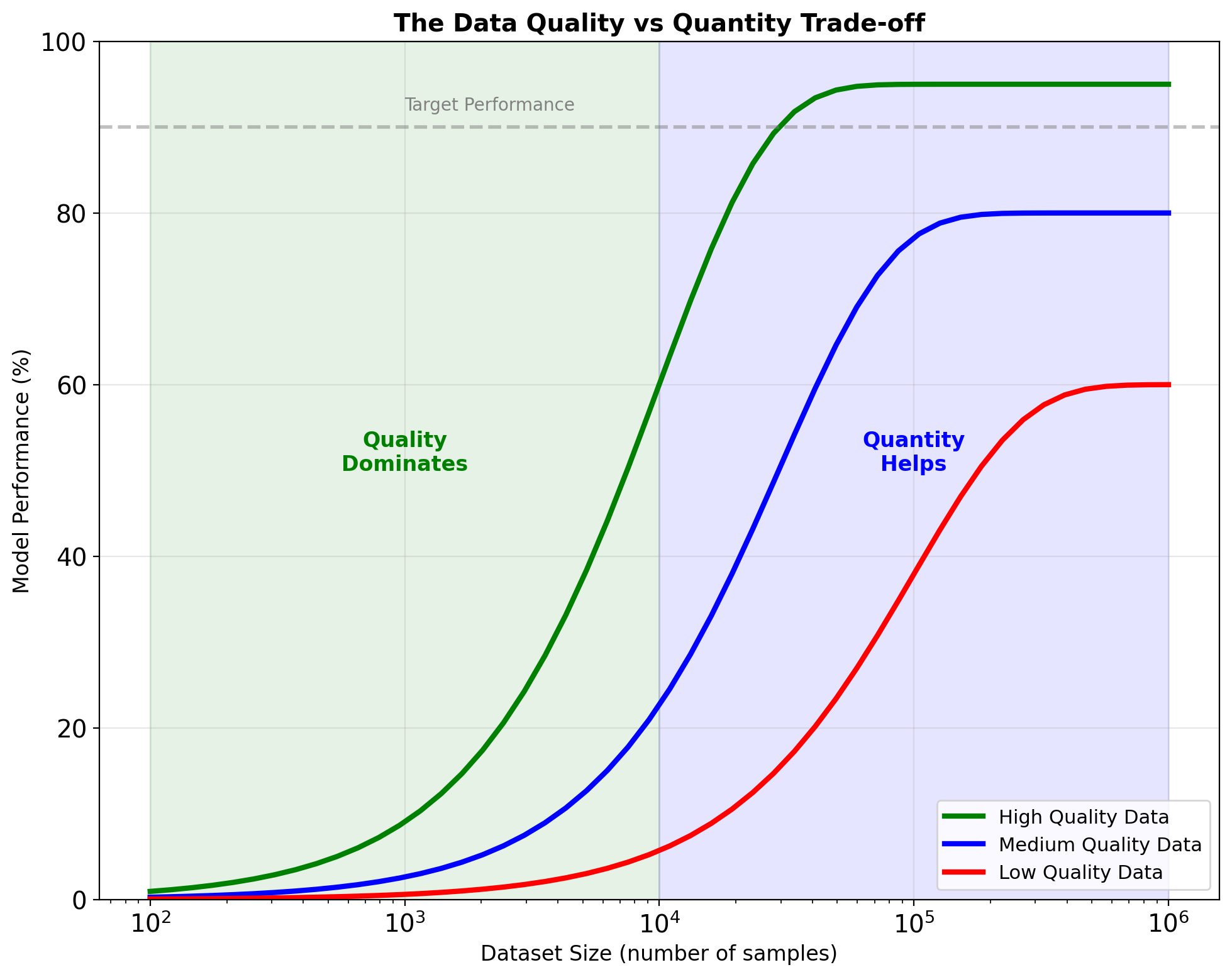

Data Quality Dominates Quantity

Clive Humby (2006)

“Data is the new oil”

But like oil, it must be refined to have value

\[\text{Model Performance} = f(\text{Data Quality}, \text{Data Quantity})\]

Illustrative Example: Data Refinement Impact

- Raw data: 10% usable (mislabeled, corrupted, outliers)

- Cleaned data: 40% usable (errors removed, imputed)

- Curated data: 90% usable (validated, balanced, relevant)

Note: Specific percentages vary by application, but quality improvement consistently outperforms quantity alone.

Representation Transforms Problem Difficulty

Representation Determines Learnability

Concentric circles: linearly inseparable in Cartesian coordinates, but trivially separable by radius in polar coordinates. Deep learning automates this search for effective representations.

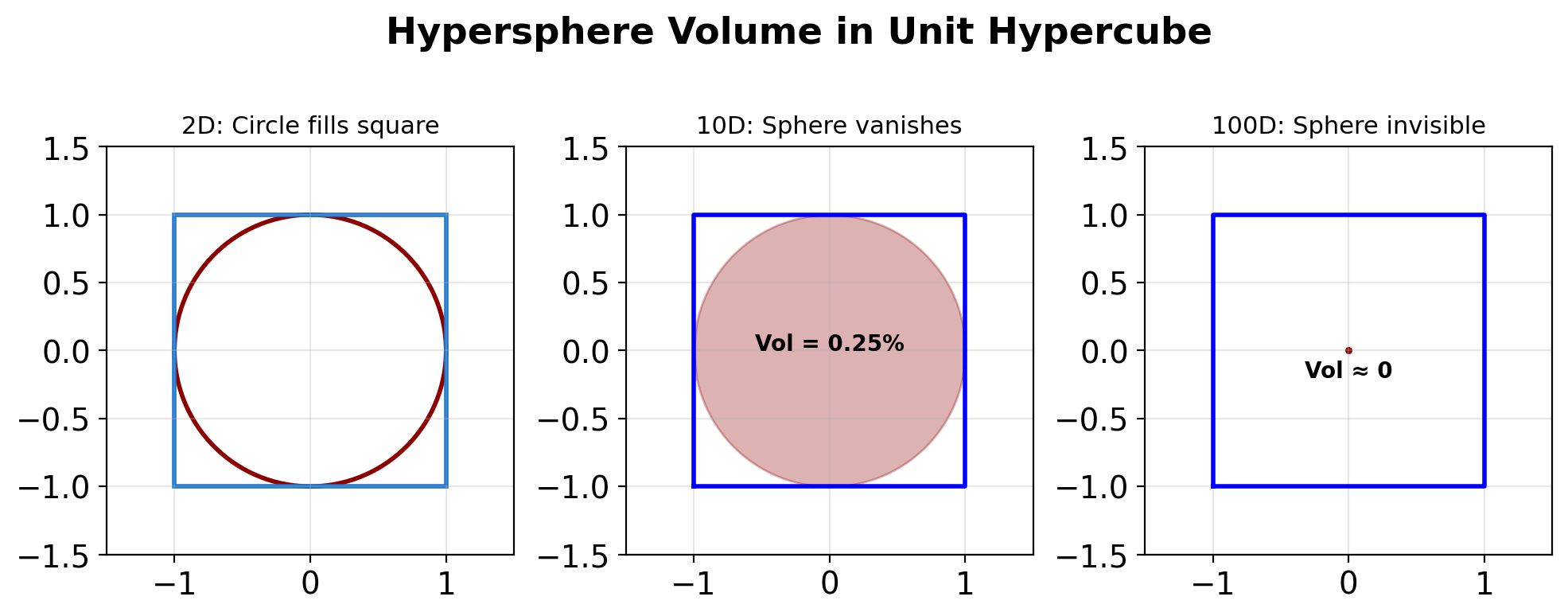

High Dimensions Break Geometric Intuition

The Curse of Dimensionality

As \(d \to \infty\):

- All points become equidistant

- Volume concentrates at surface

- Gaussian looks like uniform

- Nearest neighbors aren’t “near”

Code

d= 1: 0.050000 in outer shell

d= 2: 0.097500 in outer shell

d= 3: 0.142625 in outer shell

d= 10: 0.401263 in outer shell

d= 100: 0.994079 in outer shell

d=1000: 1.000000 in outer shell

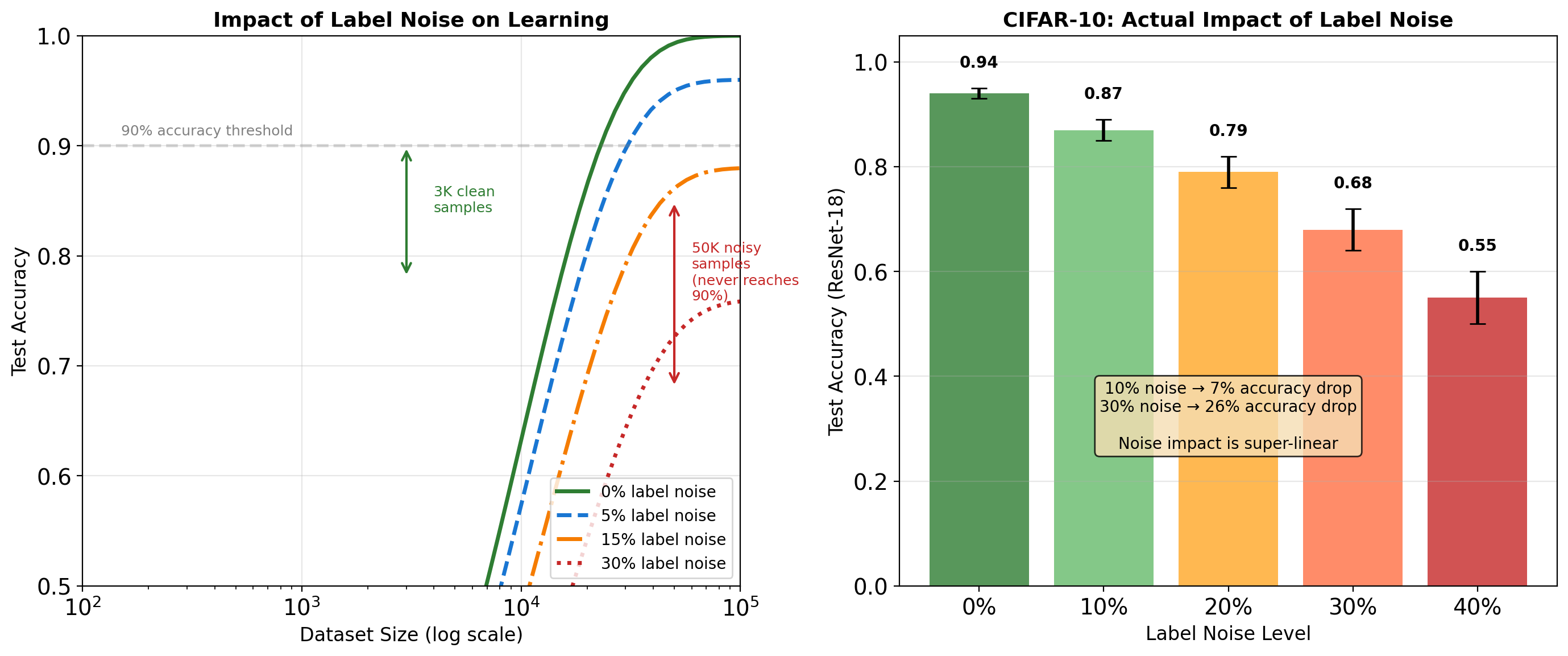

Label Noise Degrades Performance More Than Limited Data

Amazon Resume Screening: Training on Biased Data

Setup (2014-2017):

- Train model on 10 years of hiring decisions

- Input: resumes → Output: 1-5 star rating

- Goal: automate screening for top candidates

What went wrong:

- Model penalized resumes with “women’s chess club”

- Model penalized graduates of all-women’s colleges

- Model learned patterns from biased historical data

The data:

Historical hires: 85% male, 15% female

Model learned: male-coded patterns = higher ratingSystem scrapped in 2018.

Why this matters:

The model did exactly what it was trained to do - replicate patterns in historical data.

The problem: historical data reflected real-world bias.

Clean data ≠ unbiased data

- Data was accurate (real hiring decisions)

- Data was complete (10 years of records)

- Data was biased (reflected industry demographics)

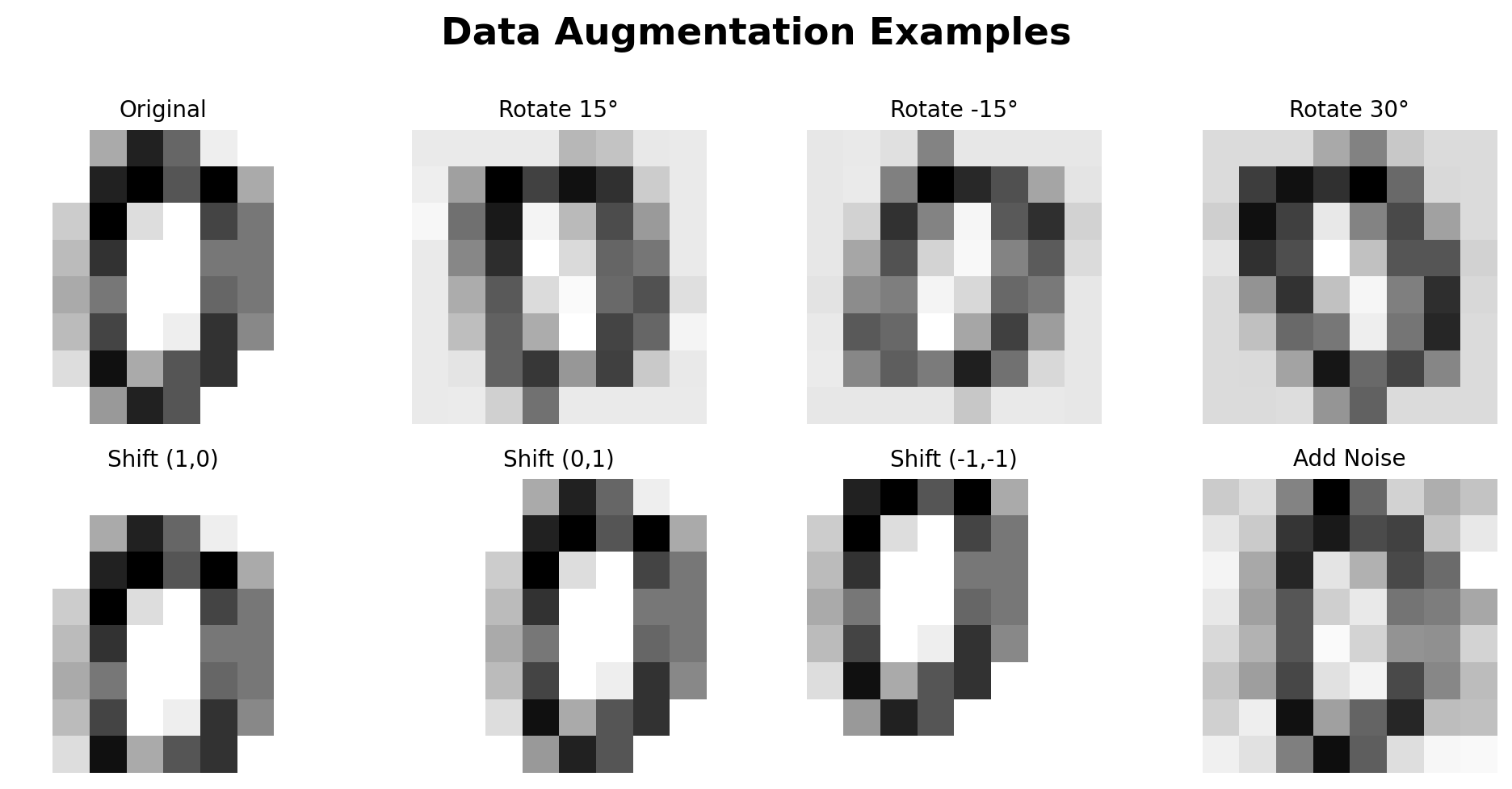

Data Augmentation: Synthetic Diversity from Limited Samples

Standard Augmentations

- Geometric: Rotation, flip, crop, scale

- Photometric: Brightness, contrast, color

- Noise: Gaussian, dropout, cutout

- Advanced: Mixup, CutMix, AutoAugment

Mathematical View

Training on augmented data: \[\min_\theta \sum_{i=1}^N \sum_{j=1}^M \mathcal{L}(f_\theta(T_j(x_i)), y_i)\]

where \(T_j\) are augmentation transforms

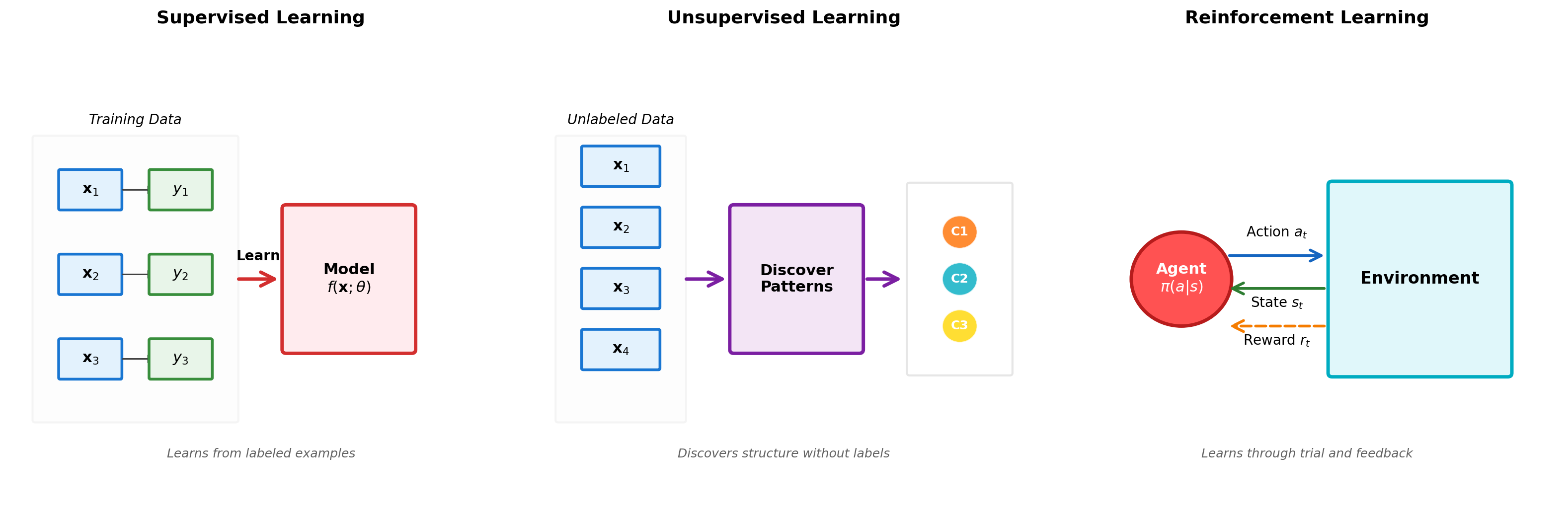

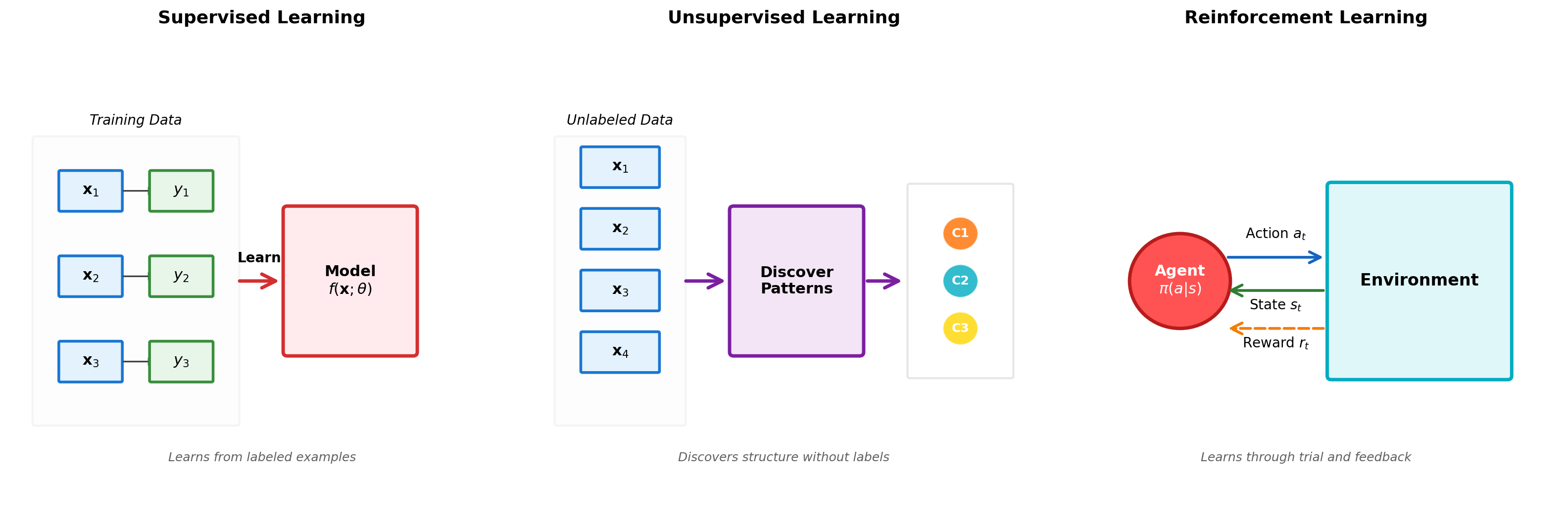

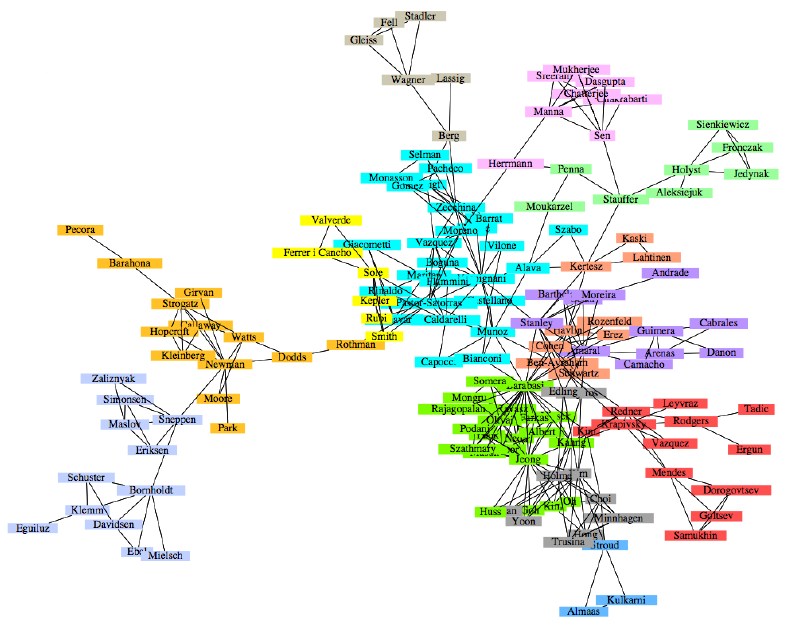

ML Learning Paradigms

Three Paradigms: Supervised, Unsupervised, Reinforcement

Modern methods combine paradigms: GPT-4 uses unsupervised pre-training on text, supervised fine-tuning on tasks, and reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF).

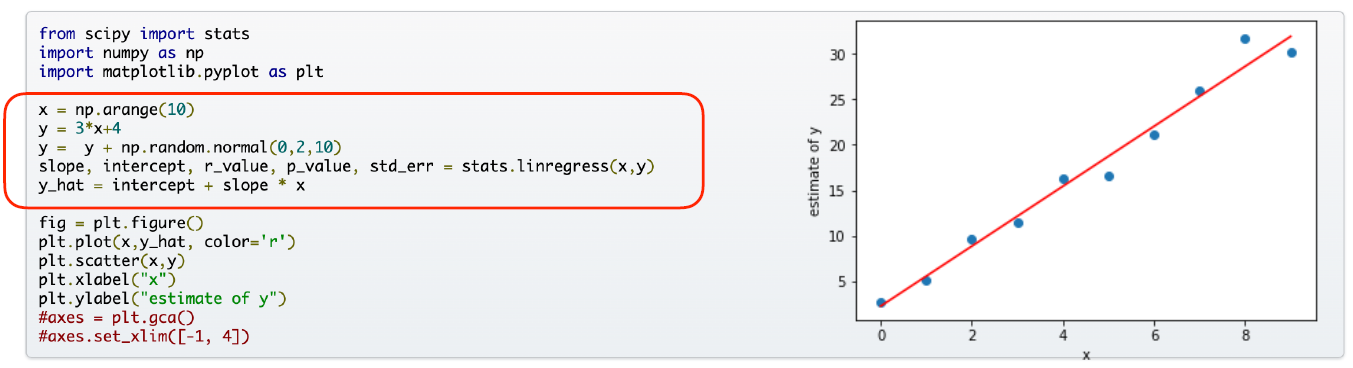

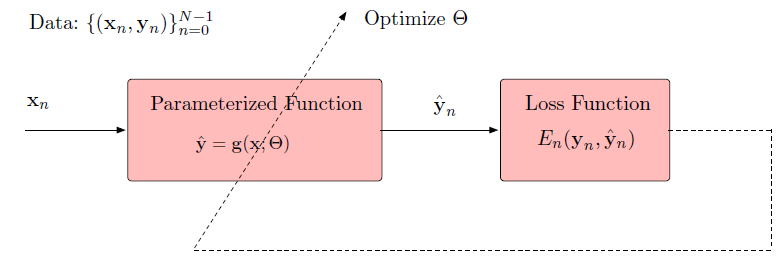

Supervised Learning: Labeled Data to Function Mapping

Problem Formulation

Given: \(\mathcal{D} = \{(\mathbf{x}_i, y_i)\}_{i=1}^N\)

Learn: \(f: \mathcal{X} \to \mathcal{Y}\)

Minimize: \(\mathcal{L}(f(\mathbf{x}), y)\)

Core Tasks

- Classification: \(y \in \{1, ..., C\}\)

- Regression: \(y \in \mathbb{R}^d\)

- Structured Prediction: \(y \in \mathcal{Y}_{\text{complex}}\)

Modern Applications

- Medical diagnosis from images

- Speech recognition

- Machine translation

- Time series forecasting

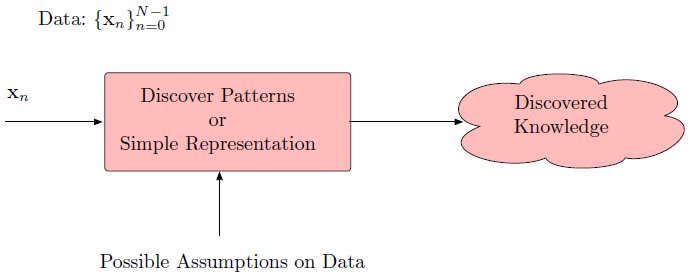

import numpy as np

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

from sklearn.metrics import accuracy_score

# Generate synthetic data

np.random.seed(42)

X = np.random.randn(1000, 10)

w_true = np.random.randn(10)

y = (X @ w_true + np.random.randn(1000)*0.1 > 0).astype(int)

# Standard supervised pipeline

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(

X, y, test_size=0.2, random_state=42

)

model = LogisticRegression(max_iter=1000)

model.fit(X_train, y_train)

train_acc = accuracy_score(y_train, model.predict(X_train))

test_acc = accuracy_score(y_test, model.predict(X_test))

print(f"Train accuracy: {train_acc:.3f}")

print(f"Test accuracy: {test_acc:.3f}")Train accuracy: 0.990

Test accuracy: 0.995Supervised Learning Training and Inference

Training Phase

Inference Phase

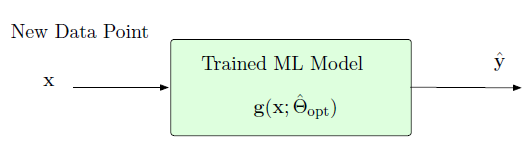

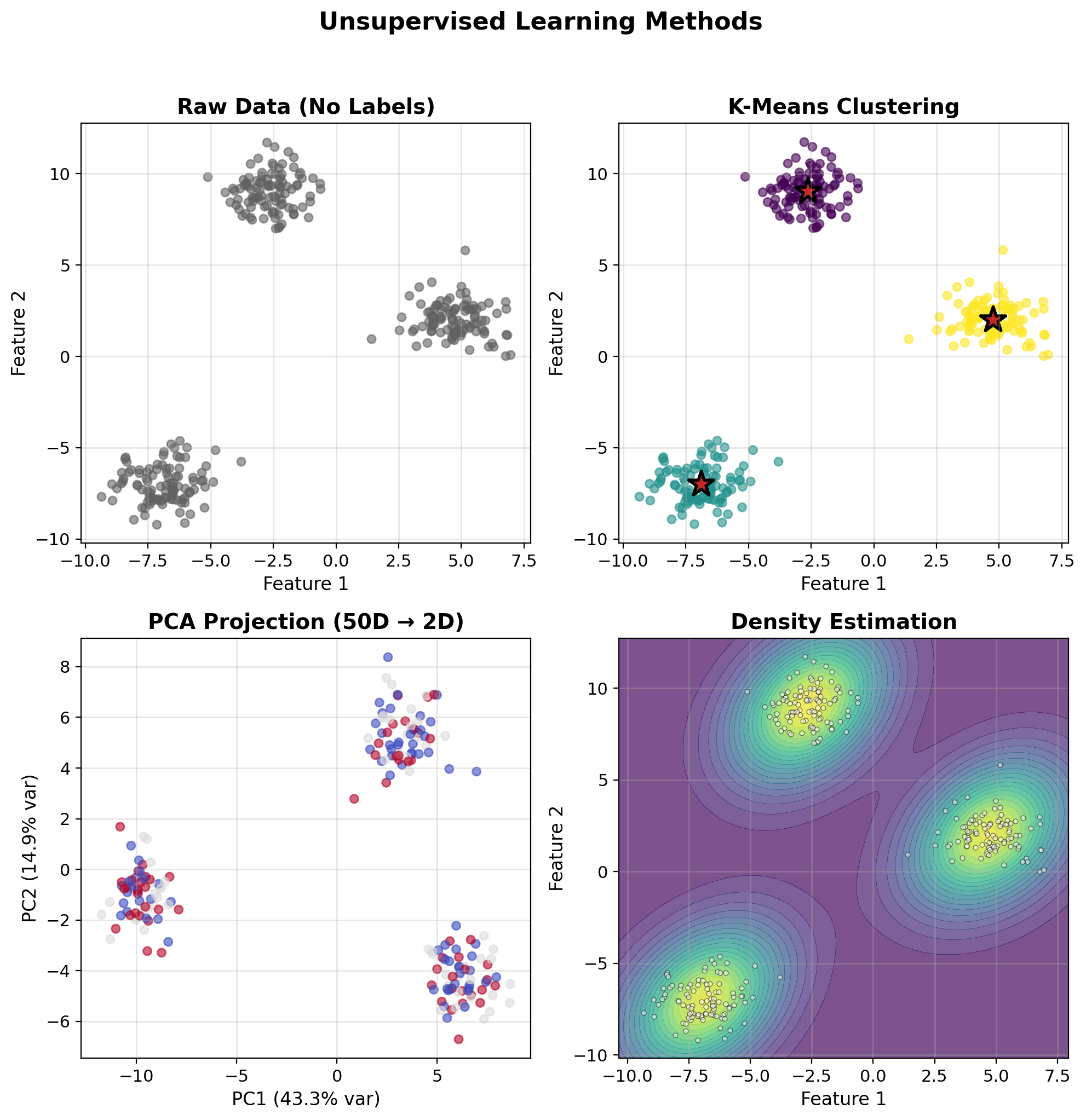

Unsupervised Learning: Structure from Unlabeled Data

No Labels, Just Data

Given: \(\mathcal{D} = \{\mathbf{x}_i\}_{i=1}^N\)

Find: Hidden patterns, structure, representations

Key Methods

- Clustering: K-means, DBSCAN, hierarchical

- Dimensionality Reduction: PCA, t-SNE, UMAP

- Density Estimation: GMM, KDE

- Representation Learning: Autoencoders

Clustering Reveals Hidden Patterns

Finding Structure in Data

Self-Supervised Learning: Labels from Data Itself

Creating Supervision from Data

Transform unsupervised → supervised by creating pretext tasks

Key Innovations

- Language Models: Predict next word (GPT)

- Masked Modeling: Predict masked parts (BERT)

- Contrastive Learning: Similar/different pairs (SimCLR)

Why It Works

- Unlimited labeled data (self-generated)

- Learns general representations

- Transfer learning to downstream tasks

Code

# Example: Simple masked prediction

def create_masked_task(sequence, mask_prob=0.15):

"""Create self-supervised task from sequence"""

masked = sequence.copy()

labels = np.full_like(sequence, -1)

mask_indices = np.random.random(len(sequence)) < mask_prob

masked[mask_indices] = 0 # [MASK] token

labels[mask_indices] = sequence[mask_indices]

return masked, labels

# Example sequence

sequence = np.array([1, 4, 2, 8, 3, 7, 5, 9])

masked_input, targets = create_masked_task(sequence)

print(f"Original: {sequence}")

print(f"Masked: {masked_input}")

print(f"Targets: {targets}")Original: [1 4 2 8 3 7 5 9]

Masked: [1 0 0 0 3 0 5 9]

Targets: [-1 4 2 8 -1 7 -1 -1]Foundation Models and Self-Supervision

Self-supervised learning powers modern foundation models like GPT and BERT

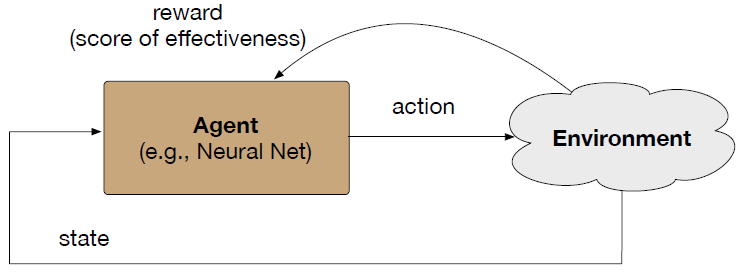

Reinforcement Learning: Sequential Decision Making

Sequential Decision Making

Components:

- State space: \(\mathcal{S}\)

- Action space: \(\mathcal{A}\)

- Reward function: \(R(s, a)\)

- Policy: \(\pi(a|s)\)

Objective: Maximize expected cumulative reward \[J(\pi) = \mathbb{E}_{\pi}\left[\sum_{t=0}^{\infty} \gamma^t r_t\right]\]

Applications

- Game playing (Chess, Go, StarCraft)

- Robotics control

- Resource allocation

- Trading strategies

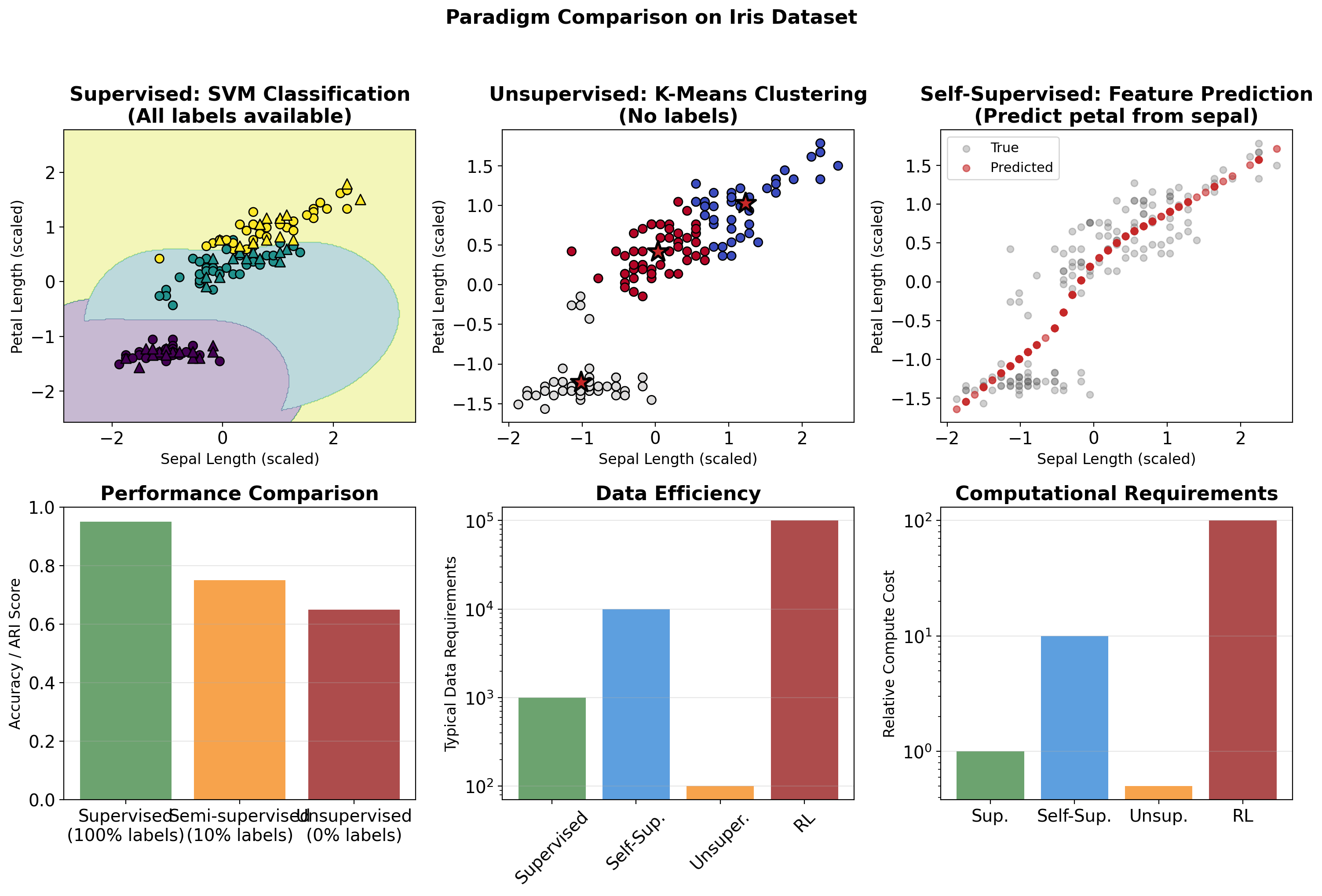

Same Problem, Different Paradigms

Label efficiency on CIFAR-10 (target: 90% accuracy):

- Supervised (full labels): 50,000 labeled images

- Semi-supervised (10% labels): 5,000 labeled + 45,000 unlabeled

- Self-supervised pretraining + fine-tune: 1,000 labeled (after ImageNet pretraining)

Transfer learning with self-supervised pretraining: 50× reduction in labeled data

Modern Methods Combine Paradigms

Semi-Supervised Learning

- Use small labeled + large unlabeled data

- Pseudo-labeling, consistency regularization

- Example: FixMatch, MixMatch

Multi-Task Learning

- Learn multiple related tasks simultaneously

- Shared representations

- Example: BERT for multiple NLP tasks

Meta-Learning

- Learn to learn

- Few-shot adaptation

- Example: MAML, Prototypical Networks

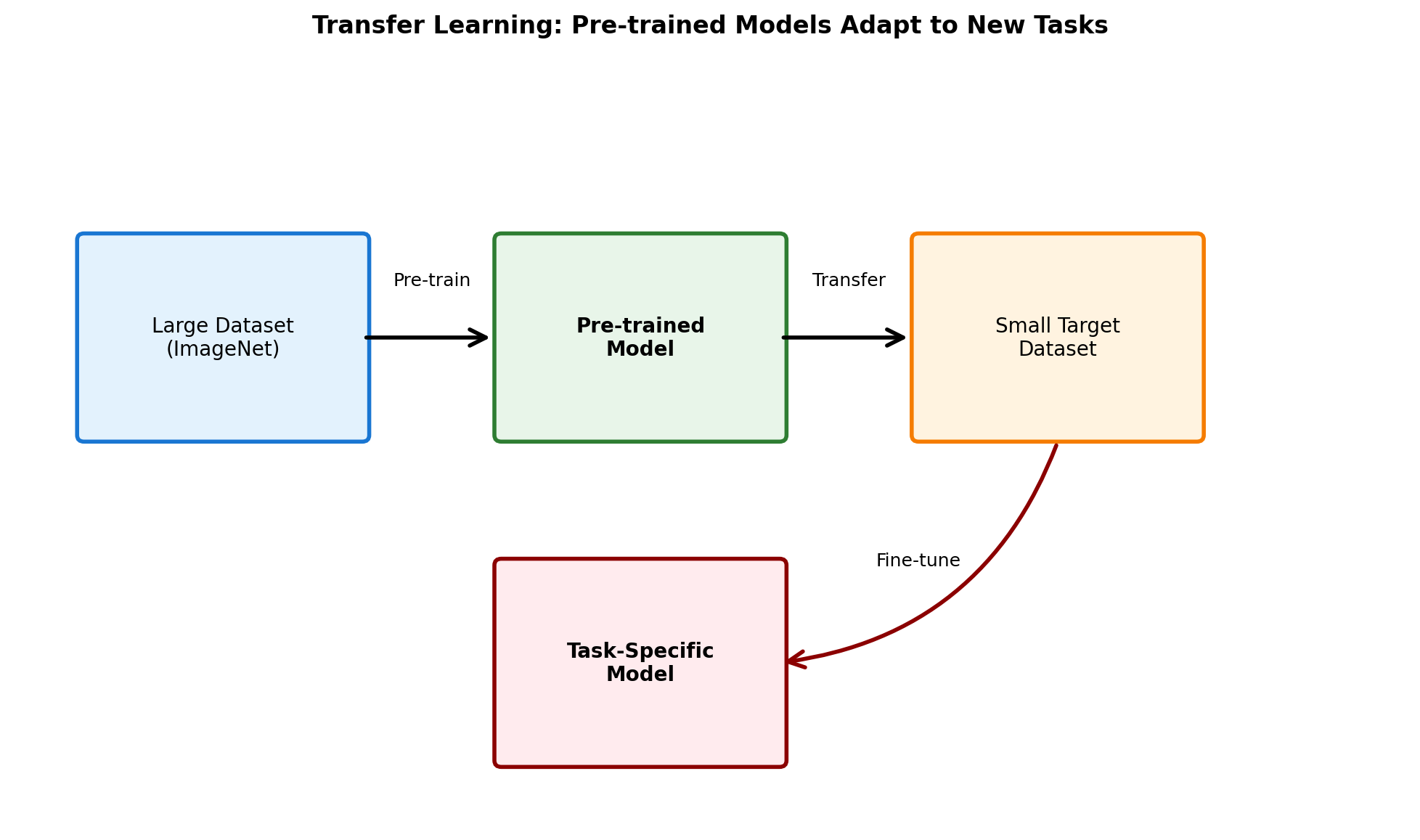

Transfer Learning Pipeline

Hybrid Learning Approaches

Modern approaches often combine paradigms for better performance

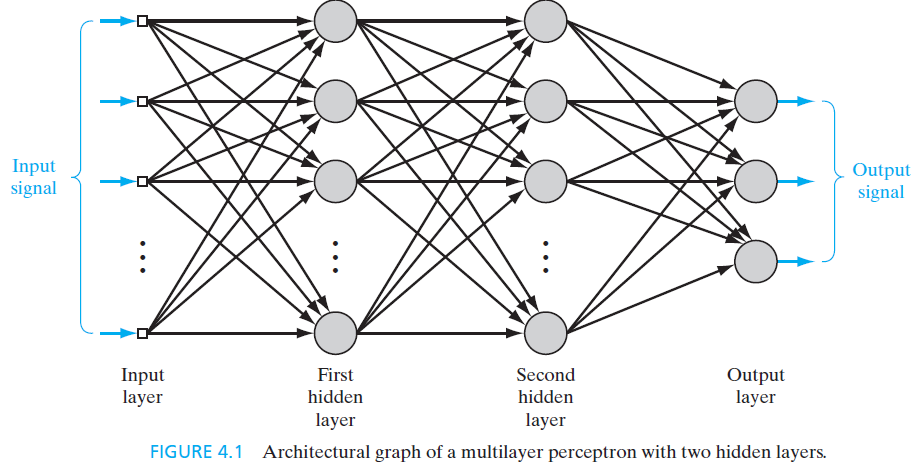

Neural Architecture

Neural Networks Form a Rich Hypothesis Class

Multilayer Perceptron (MLP): Fully connected feedforward network

Architecture Components

- Input layer: Raw features \(\mathbf{x} \in \mathbb{R}^d\)

- Hidden layers: Learned representations

- Output layer: Task-specific predictions

- Connections: All-to-all between layers

Why “Rich” Hypothesis Class?

- Each neuron: Nonlinear transformation

- Composition: Exponential expressivity

- Universal approximation capability

Defn: Deep Neural Network

A neural network with more than one hidden layer. Depth enables hierarchical feature learning: early layers learn simple features, deeper layers learn complex abstractions.

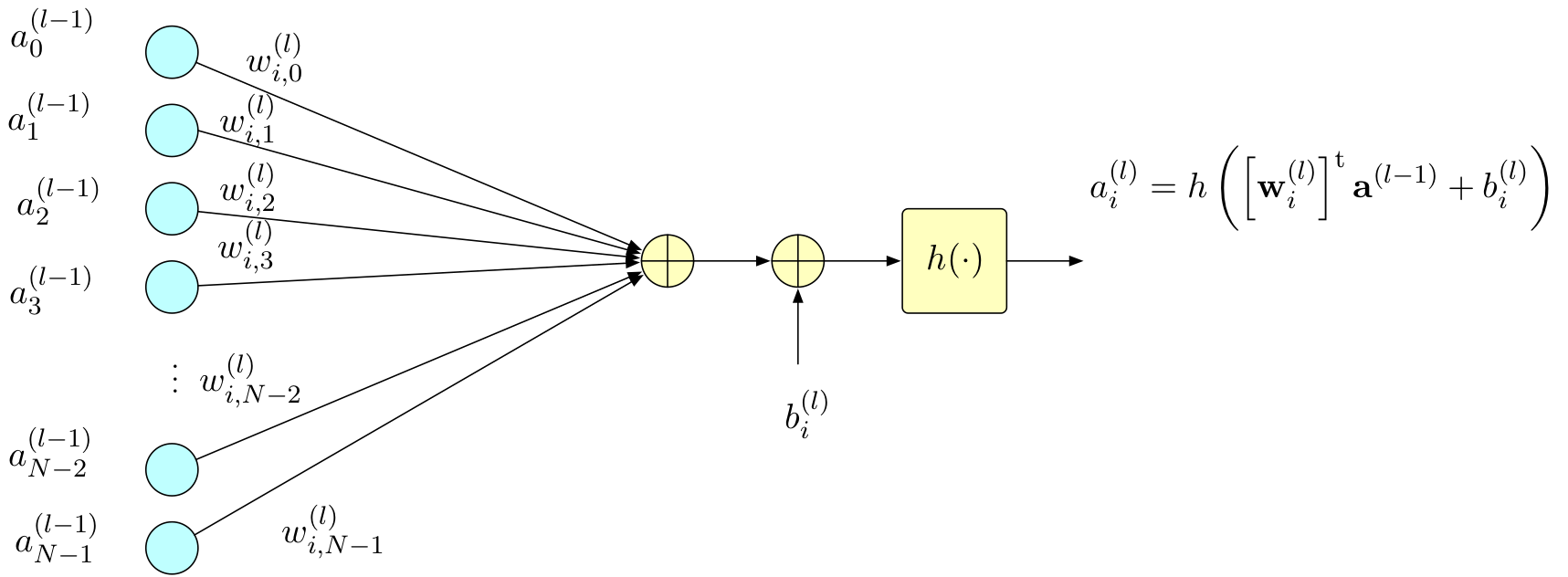

Single Neuron Computation

Forward Computation

At neuron \(i\) in layer \(l\):

\[a_i^{(l)} = h\left(\left[\mathbf{w}_i^{(l)}\right]^\top \mathbf{a}^{(l-1)} + b_i^{(l)}\right)\]

where:

- \(\mathbf{a}^{(l-1)}\): Previous layer activations

- \(\mathbf{w}_i^{(l)}\): Weight vector for neuron \(i\)

- \(b_i^{(l)}\): Bias term

- \(h(\cdot)\): Activation function

Matrix Form (Entire Layer)

\[\mathbf{a}^{(l)} = h\left(\mathbf{W}^{(l)} \mathbf{a}^{(l-1)} + \mathbf{b}^{(l)}\right)\]

- Parallelizes computation

- Enables GPU acceleration

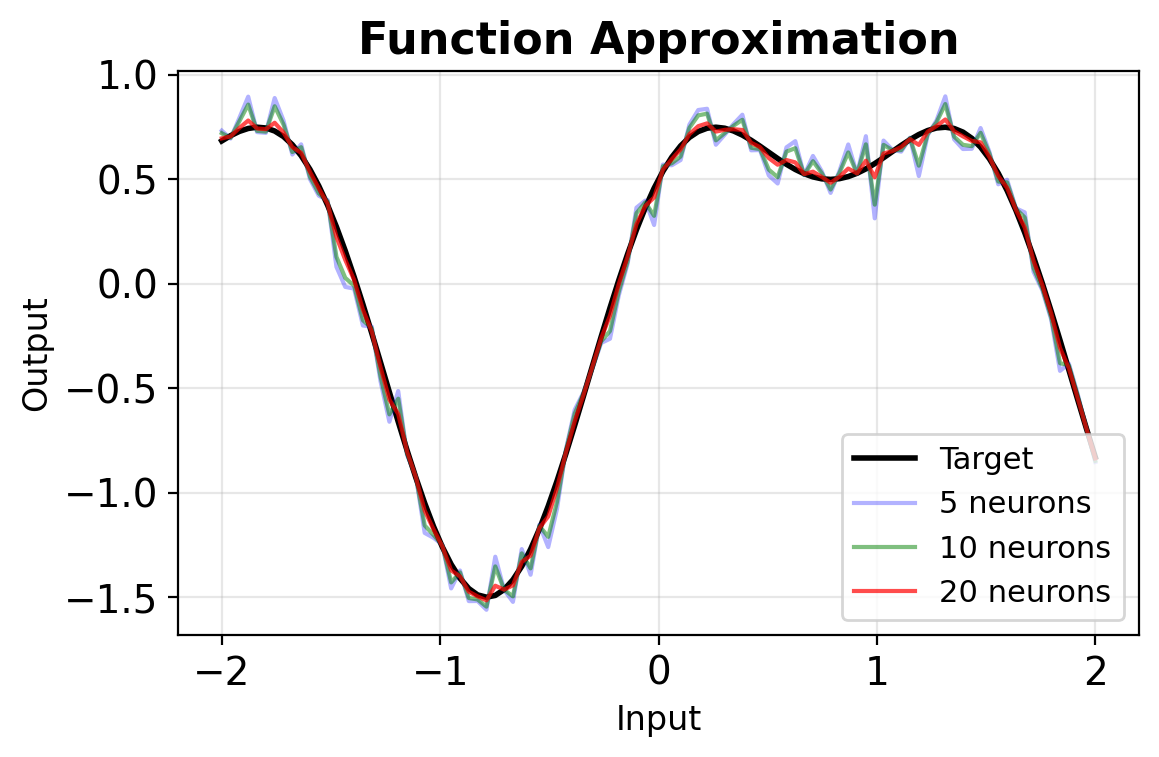

Universal Approximation: Existence Guarantee

Cybenko (1989), Hornik et al. (1989)

A feedforward network with:

- Single hidden layer

- Finite number of neurons

- Non-polynomial activation

can approximate any continuous function on compact subset of \(\mathbb{R}^n\) to arbitrary accuracy

Critical word: CAN

The theorem guarantees such networks exist. Finding them through training is different.

Preview

Detailed treatment later: approximation theory, width vs depth, practical training implications

Width vs Depth: Why We Use Deep Networks

Width-only (single hidden layer)

Universal approximation guarantees this works, but:

- May require exponentially many neurons

- Example: parity function on n bits needs \(2^{n-1}\) hidden units

- Theorem says existence, not efficiency

Depth (multiple layers)

- More parameter-efficient representation

- Polynomial neurons vs exponential

- Hierarchical features emerge

- Same expressivity, fewer parameters

Why depth matters: Practical networks need efficient representations

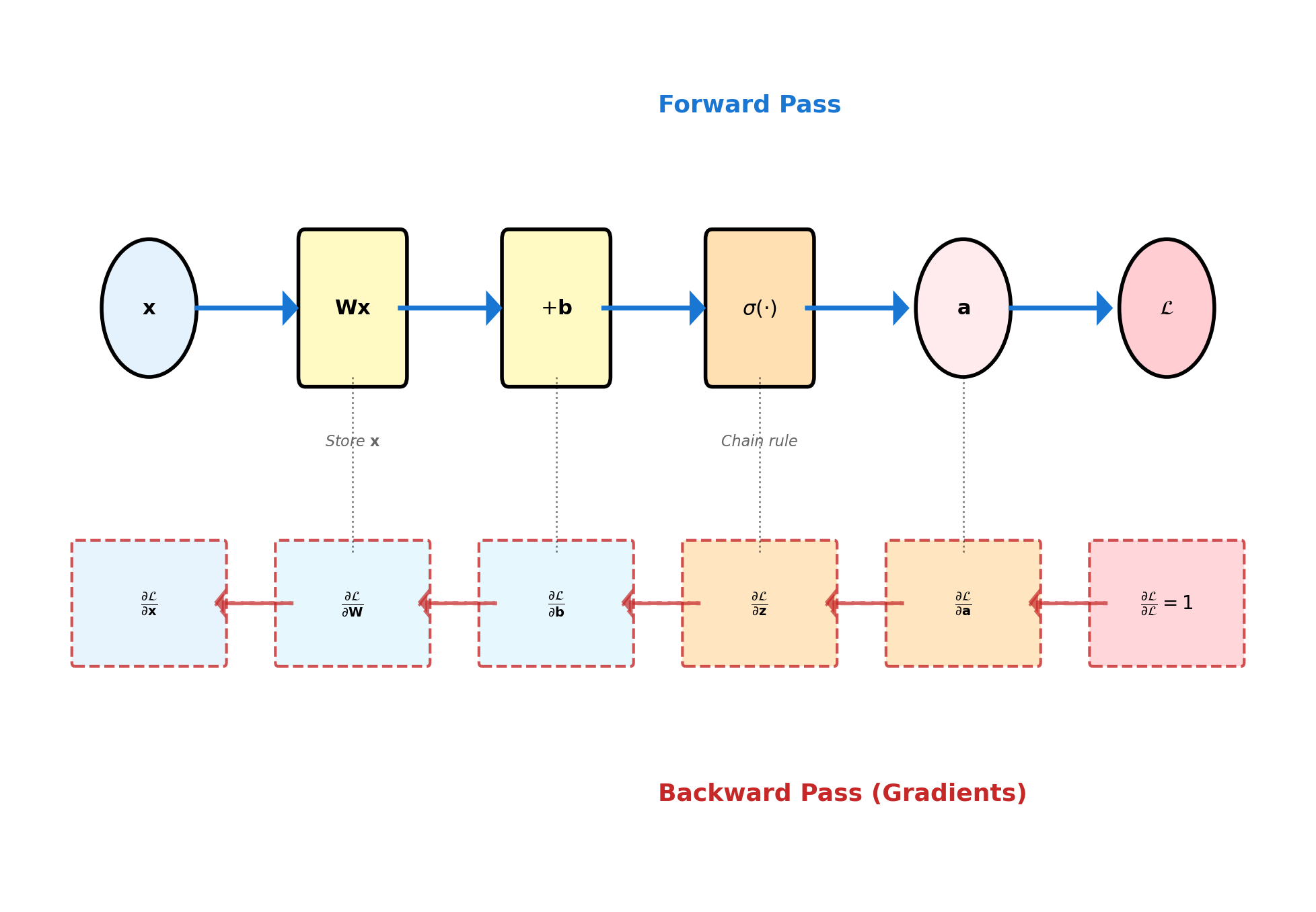

Forward and Backward Pass

Implementation

class Layer:

def forward(self, x):

# Store for backward pass

self.x = x

# Linear transformation

self.z = np.dot(x, self.W) + self.b

# Apply activation

self.a = self.activation(self.z)

return self.a

def backward(self, grad_output):

# Chain rule through activation

grad_z = grad_output * \

self.activation_derivative(self.z)

# Parameter gradients

self.grad_W = np.dot(self.x.T, grad_z)

self.grad_b = np.sum(grad_z, axis=0)

# Input gradient for previous layer

grad_input = np.dot(grad_z, self.W.T)

return grad_inputComputational Graph

Network Capacity and Depth

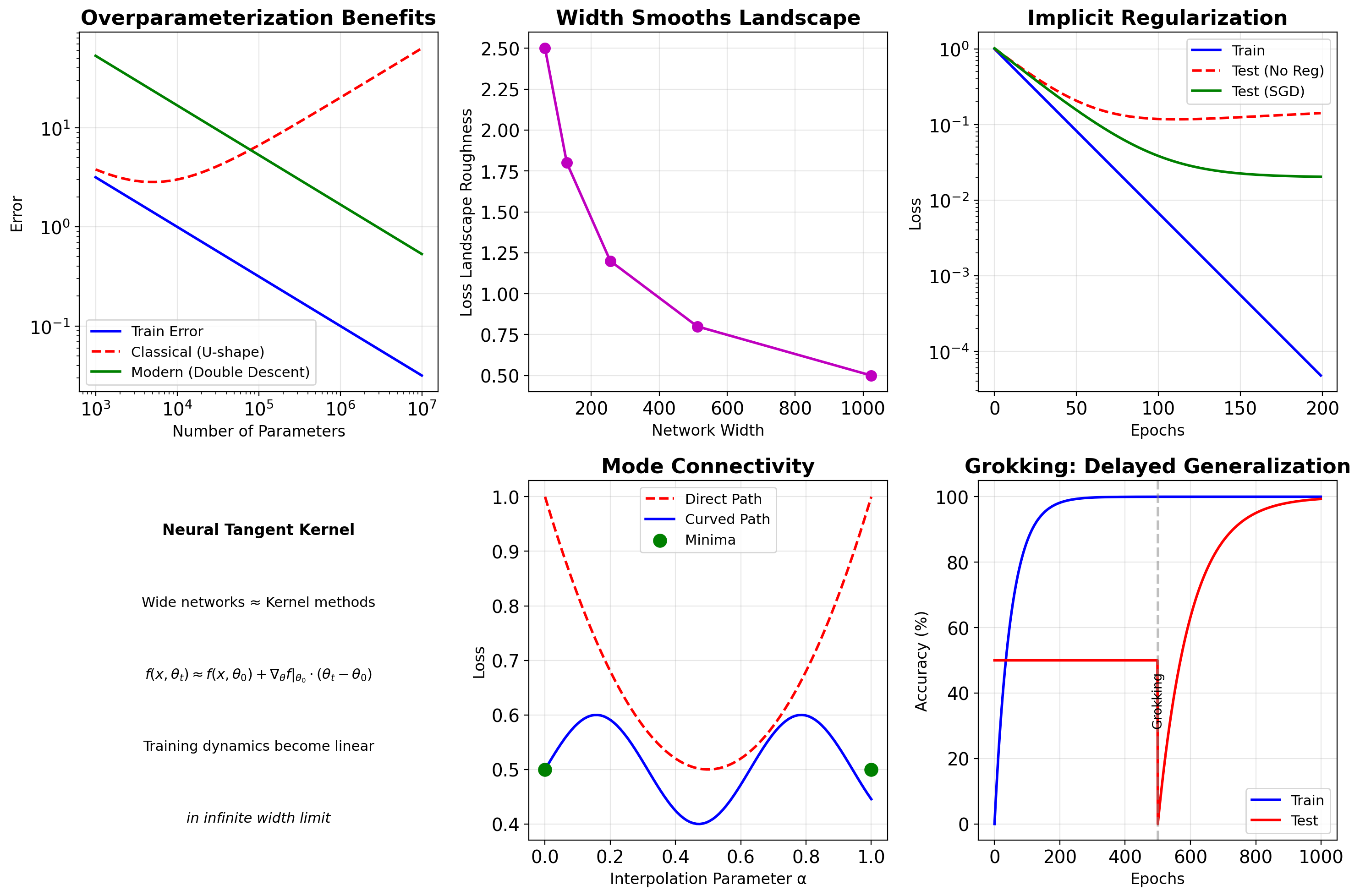

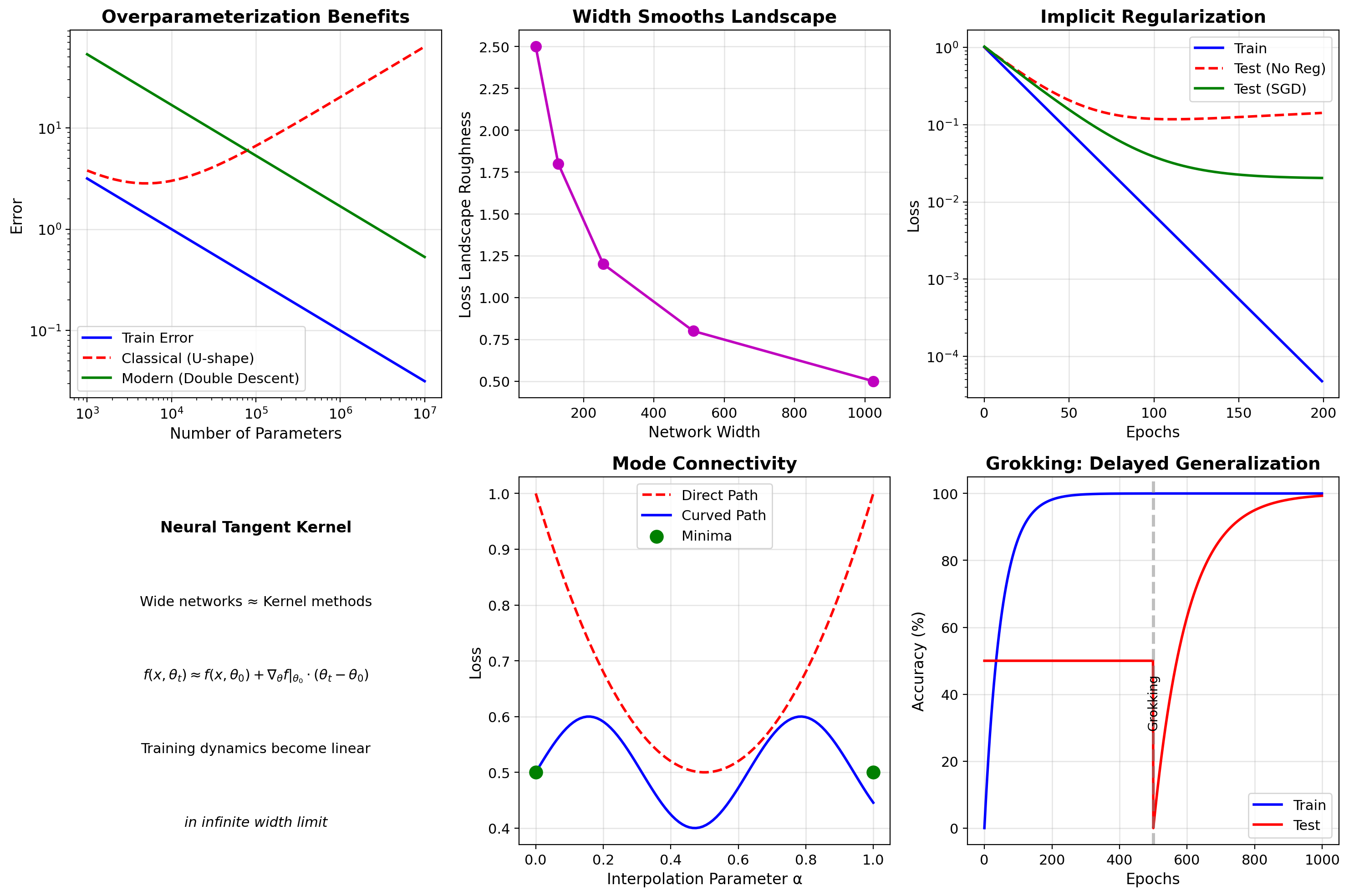

The Optimization Landscape

Loss Surfaces in High Dimensions

Mathematical Reality

In \(d\) dimensions with \(n\) parameters:

- Critical points: \(\mathcal{O}(e^n)\)

- Most are saddle points, not local minima

- Minima often connected by low-loss paths

Empirical Observations

- Loss landscapes are surprisingly well-behaved

- Wide networks have smoother landscapes

- Overparameterization helps optimization

- Mode connectivity phenomenon

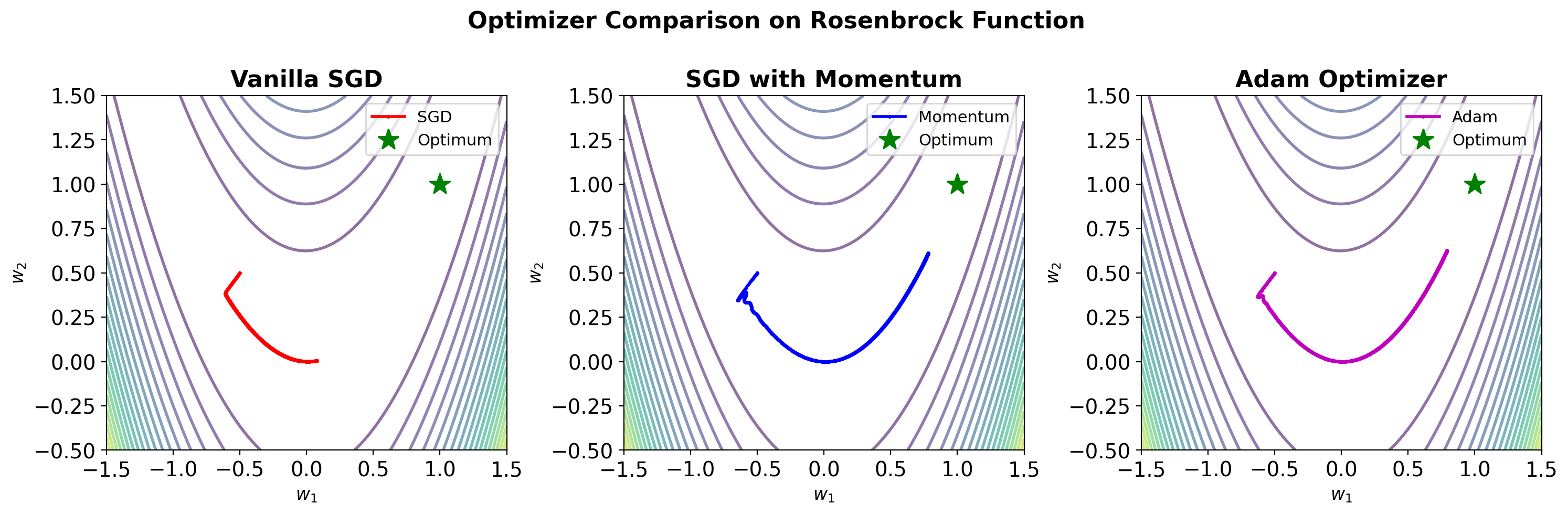

Stochastic Gradient Descent and Variants

Code

def sgd(w, grad, lr=0.01):

return w - lr * grad

def sgd_momentum(w, grad, velocity, lr=0.01, beta=0.9):

velocity = beta * velocity + lr * grad

return w - velocity, velocity

def adam(w, grad, m, v, t, lr=0.001, beta1=0.9, beta2=0.999, eps=1e-8):

m = beta1 * m + (1 - beta1) * grad

v = beta2 * v + (1 - beta2) * grad**2

m_hat = m / (1 - beta1**t)

v_hat = v / (1 - beta2**t)

return w - lr * m_hat / (np.sqrt(v_hat) + eps), m, v

Lottery Ticket Hypothesis: Sparse Subnetworks at Initialization

Frankle & Carbin (2019)

“Dense networks contain sparse subnetworks that can train to comparable accuracy from the same initialization”

Implications

- Networks are vastly overparameterized

- Winning tickets exist at initialization

- Pruning can maintain performance

- Structure matters more than we thought

Practical Impact

\[\text{Parameters: } 100M \to 10M\] \[\text{Performance: } 95\% \to 94.5\%\]

Why this matters:

Storage:

- 100M: ~400MB (too large for mobile)

- 10M: ~40MB (fits on phone)

Speed:

- 100M: ~100ms per image

- 10M: ~10ms per image (real-time)

Training:

- 100M: 5 days on single GPU

- 10M: 12 hours (faster experiments)

Detailed treatment: Network pruning and efficient architectures

Modern Theoretical Insights

Why Deep Networks Generalize

Neural Networks Memorize Random Labels Yet Generalize on Real Data

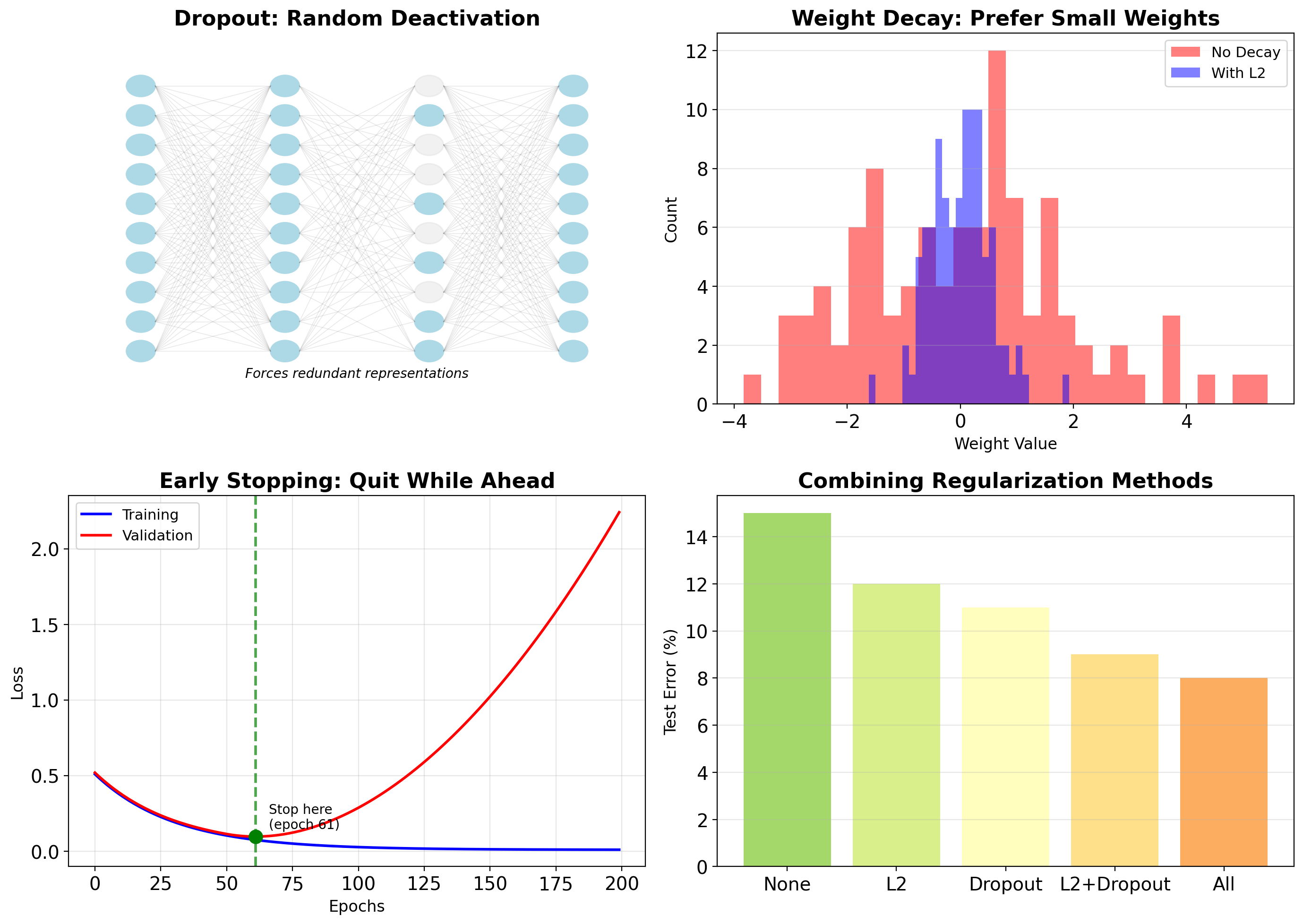

Regularization Techniques: Dropout and Weight Decay

Architecture Embeds Domain Knowledge

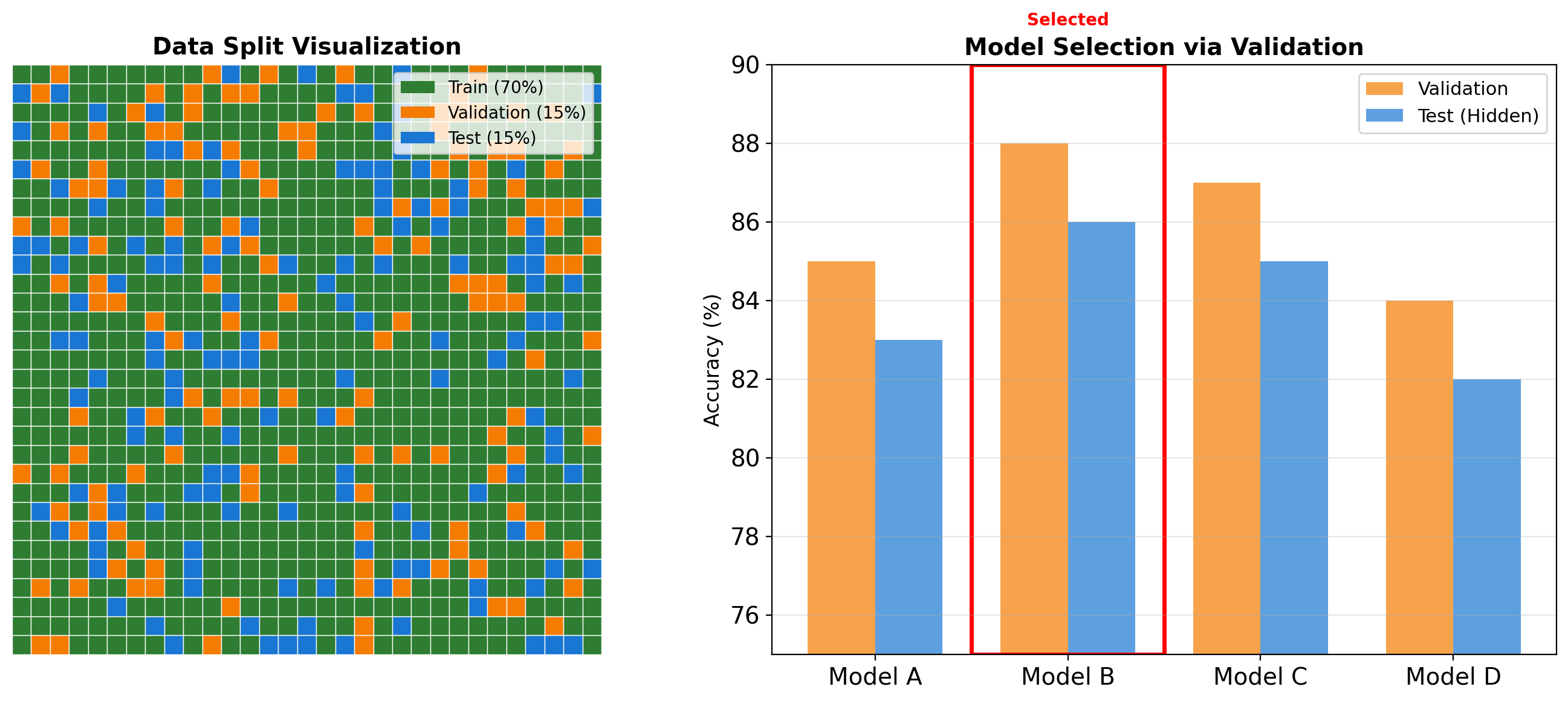

Train/Validation/Test: Sacred Separation

WARNING: Data Contamination

Never touch test data until final evaluation - validation data guides all decisions

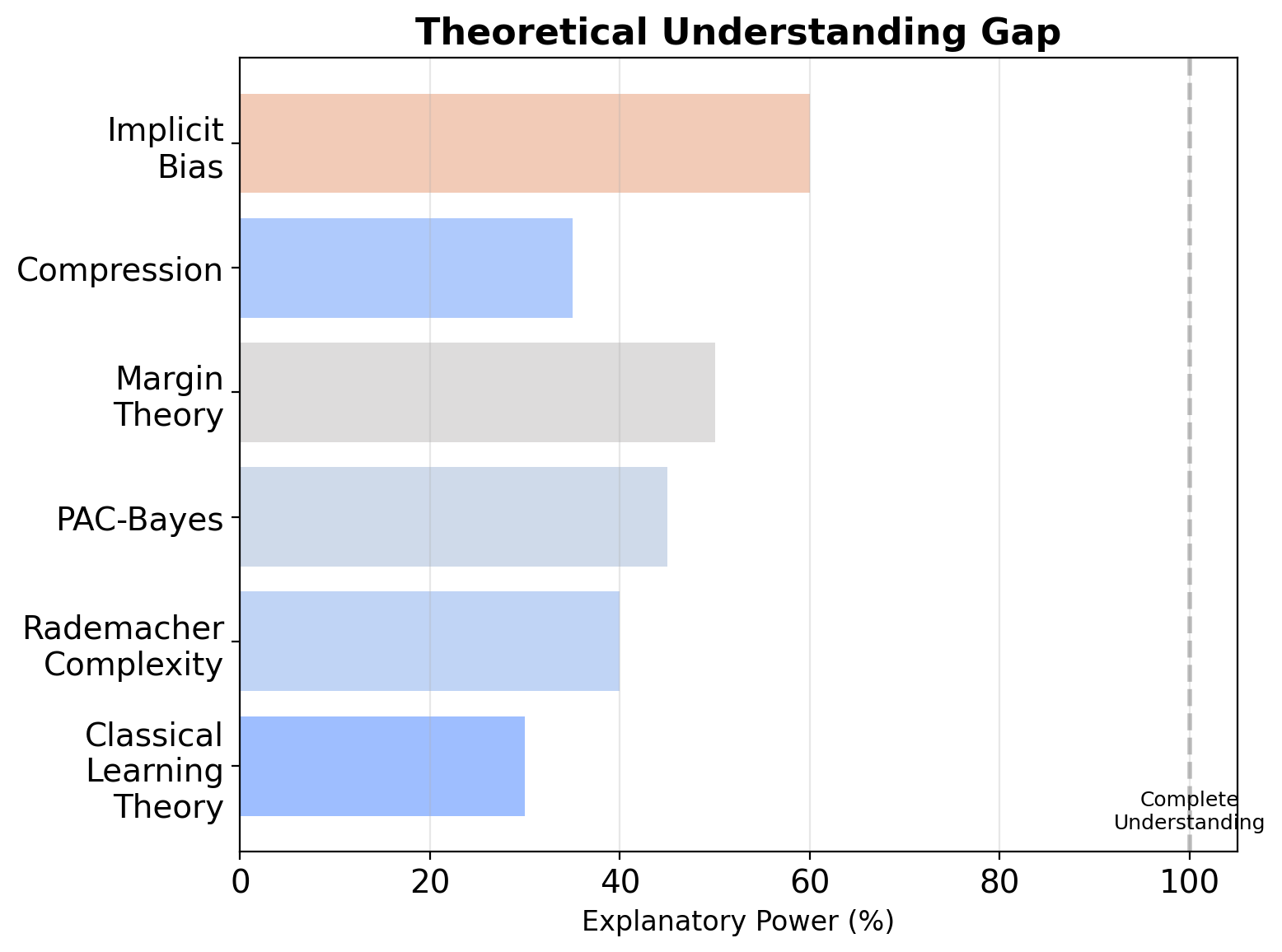

Generalization Remains Partially Unexplained

What We Don’t Understand

Why does SGD find generalizing solutions?

Networks can memorize random labels perfectly,

yet SGD finds patterns when labels are real

Why does overparameterization help?

10x more parameters than samples should overfit,

but often improves test accuracy

What is the role of depth?

Shallow wide networks have same capacity,

but deep networks generalize better

How do transformers generalize?

No convolutions, no recurrence,

yet state-of-the-art on vision and language

Note: No single theory fully explains deep learning generalization. Active research area.

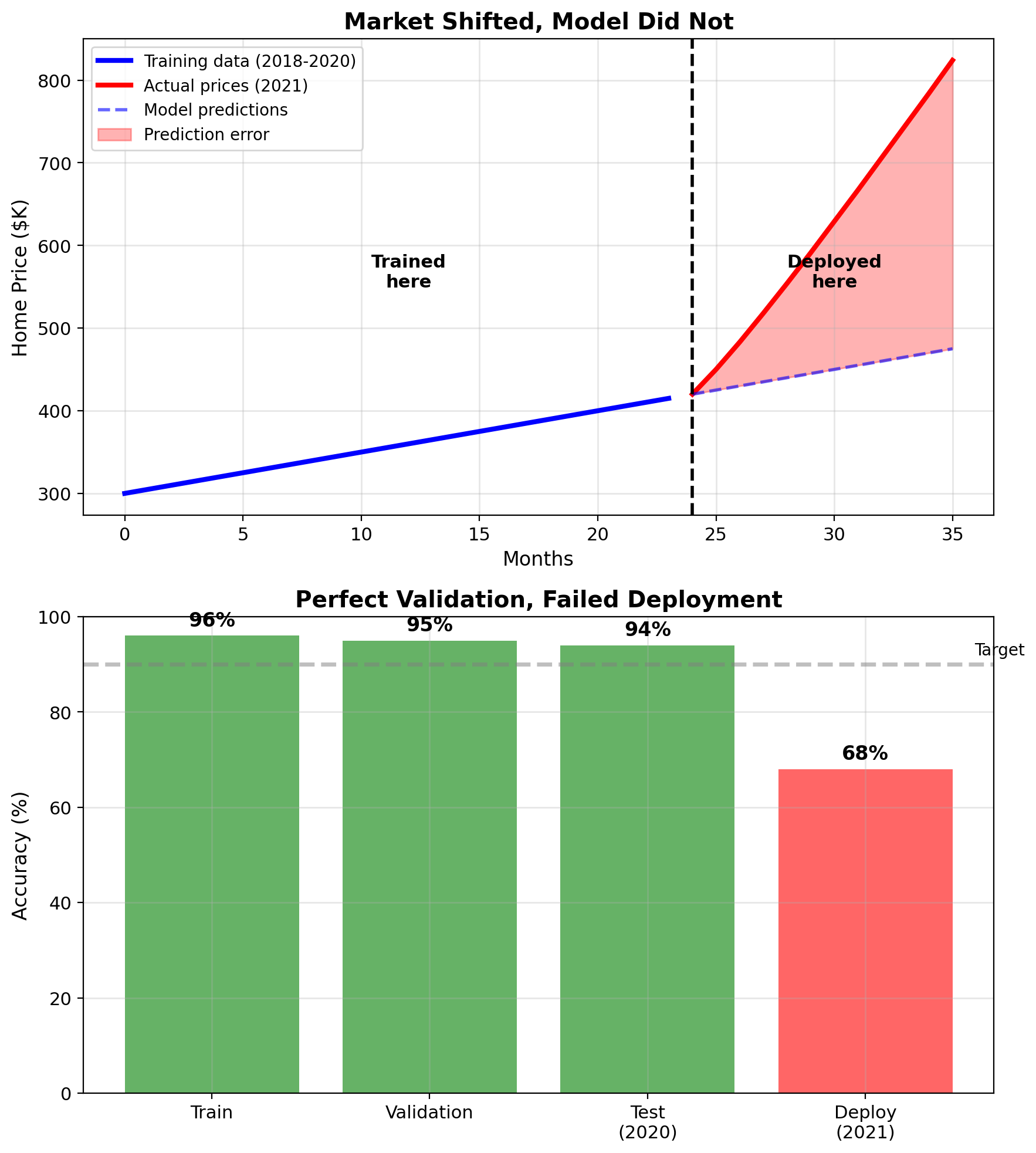

Zillow Home Pricing: When the World Changes

Setup (2018-2021):

- Predict home values for algorithmic buying

- Train on 2018-2020 housing data

- Validation: 95% accurate (within 5% of price)

- Test set: 94% accurate

- Model looked excellent

Deployment (2021):

- COVID shifts housing market

- Model systematically underpredicts by $80K-$100K

- Loss: $500M+ before shutting down

What happened:

Training data came from stable market. Deployment happened during rapid market shift. Model kept predicting pre-COVID prices.

The problem:

All your validation tools assume the future looks like the past. When the world changes, models trained on historical data fail.

Train/val/test all from 2018-2020: Model learns pre-COVID patterns

Deploy in 2021: COVID changed everything

Result: Model is wrong, but doesn't know it's wrongThis is not a rare edge case - markets shift, user behavior changes, new products emerge. Distribution shift is common.

Building Systems Despite Incomplete Theory

What theory doesn’t fully explain

- Why SGD finds generalizing solutions (not just any minimum)

- How overparameterization helps (contradicts classical theory)

- What depth contributes beyond expressivity

- Why some architectures work better than others

Classical theory predicts

- More parameters than data causes overfitting

- Zero training error means poor generalization

- Simpler models should always win

Modern practice shows

- Overparameterized networks generalize well

- Zero training loss often gives best test performance

- Complex models frequently outperform simple ones

How we build systems anyway

Empirical validation:

- Train/validation/test splits (always)

- Monitor generalization gap continuously

- Trust validation performance over theory

Defensive engineering:

- Start simple, add complexity gradually

- Regularize by default (dropout, weight decay)

- Early stopping when validation degrades

- Ensemble multiple models for robustness

Course approach:

- Learn techniques that work empirically

- Understand intuition for why they might work

- Recognize when theory provides guarantees

- Know when you’re operating without guarantees

Many fundamental questions remain open research problems.

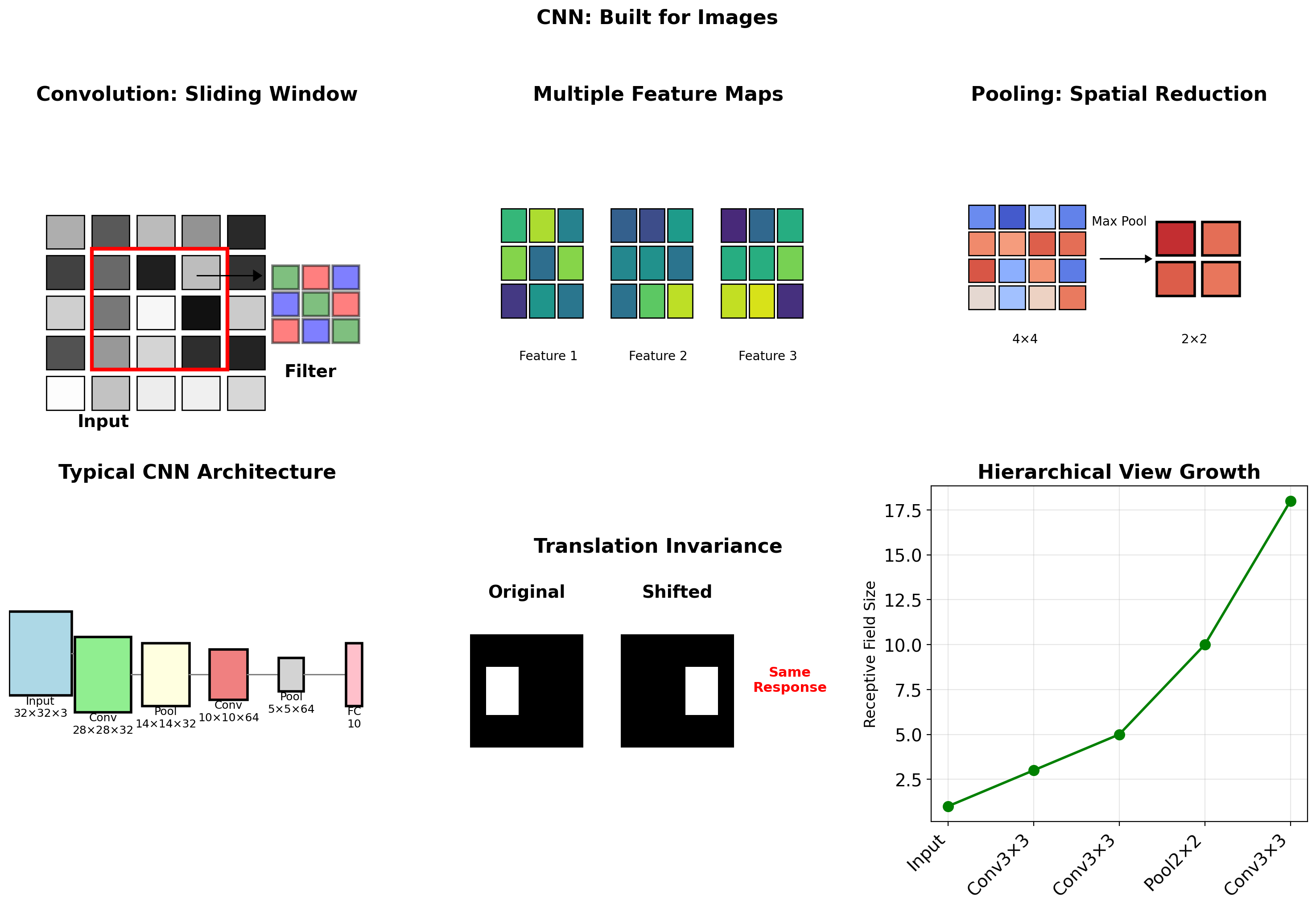

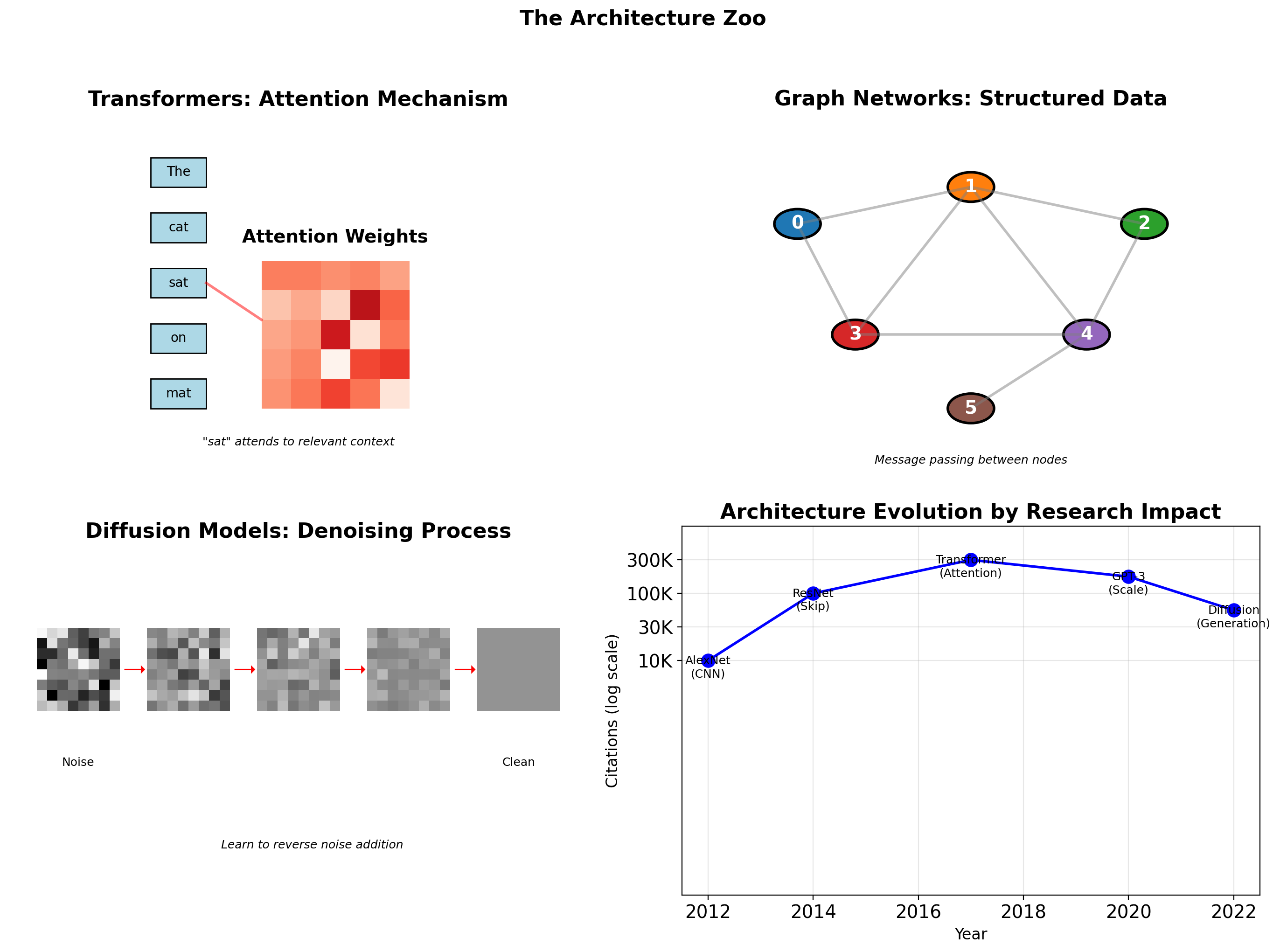

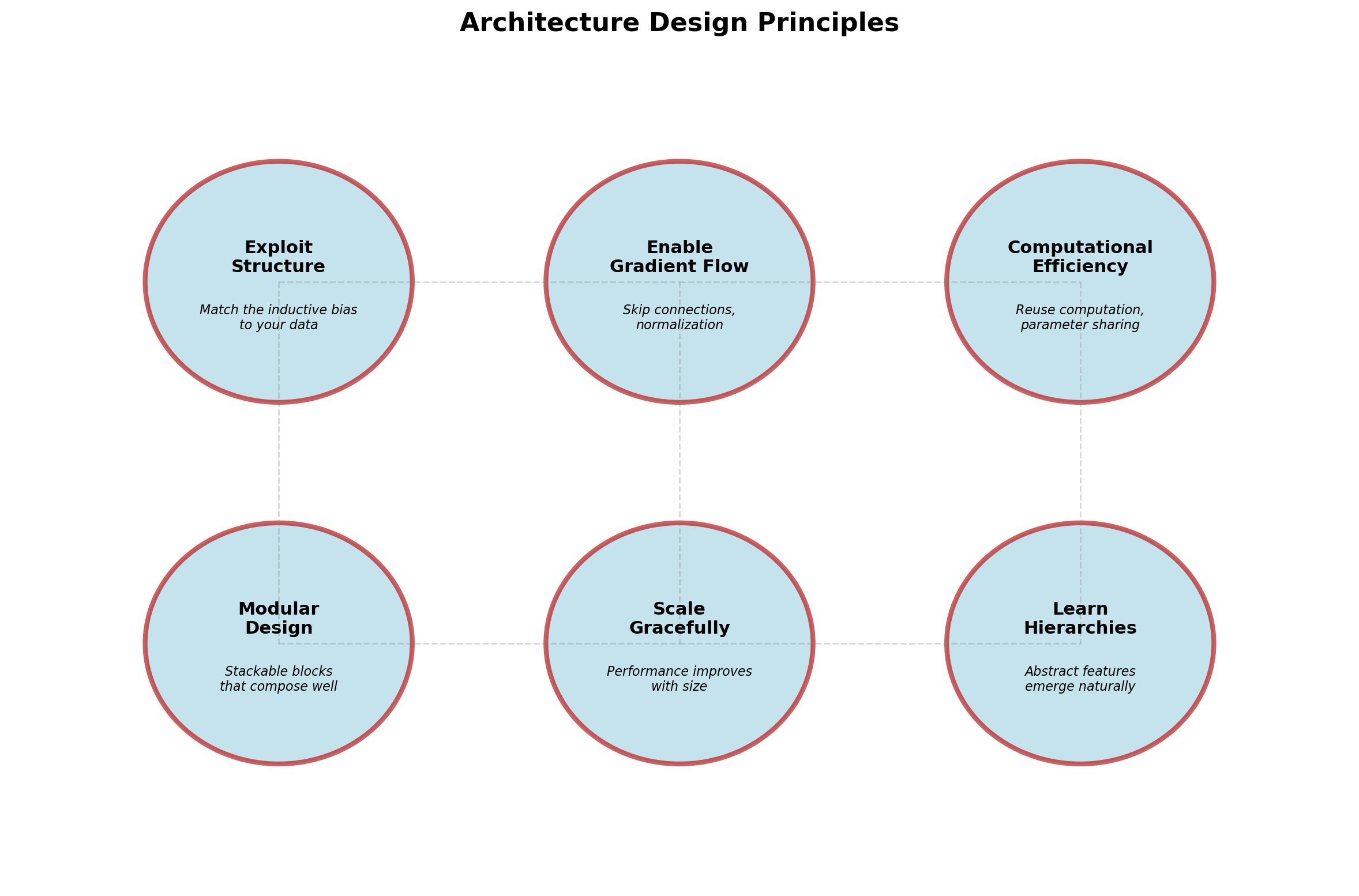

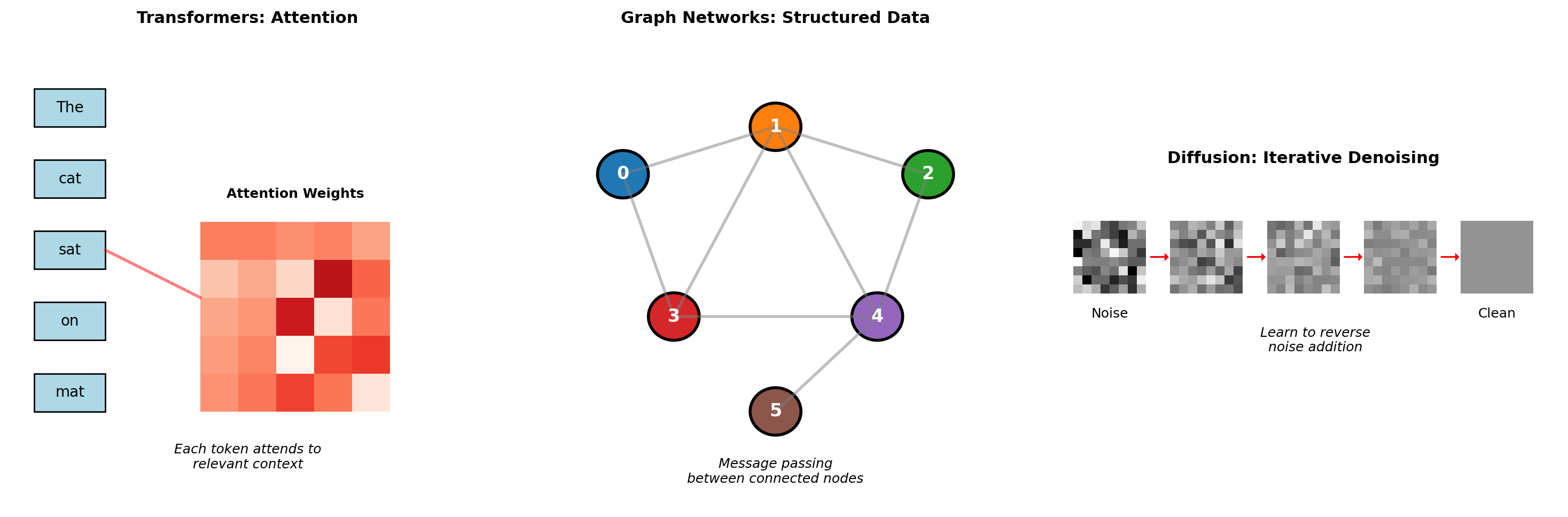

Modern Deep Architectures

Convolutional Networks: Exploiting Spatial Structure

Preview: Transformers, Graph Networks, and Diffusion Models

Building a Simple CNN

import numpy as np

class Conv2D:

def __init__(self, in_channels, out_channels, kernel_size=3):

self.in_channels = in_channels

self.out_channels = out_channels

self.kernel_size = kernel_size

# Initialize filters

self.filters = np.random.randn(

out_channels, in_channels, kernel_size, kernel_size

) * 0.1

self.bias = np.zeros(out_channels)

def forward(self, x):

batch, in_c, height, width = x.shape

out_h = height - self.kernel_size + 1

out_w = width - self.kernel_size + 1

output = np.zeros((batch, self.out_channels, out_h, out_w))

# Convolution operation

for b in range(batch):

for oc in range(self.out_channels):

for h in range(out_h):

for w in range(out_w):

# Extract patch

patch = x[b, :, h:h+self.kernel_size, w:w+self.kernel_size]

# Convolve with filter

output[b, oc, h, w] = np.sum(patch * self.filters[oc]) + self.bias[oc]

return output

class MaxPool2D:

def __init__(self, pool_size=2):

self.pool_size = pool_size

def forward(self, x):

batch, channels, height, width = x.shape

out_h = height // self.pool_size

out_w = width // self.pool_size

output = np.zeros((batch, channels, out_h, out_w))

for h in range(out_h):

for w in range(out_w):

h_start = h * self.pool_size

w_start = w * self.pool_size

pool_region = x[:, :, h_start:h_start+self.pool_size,

w_start:w_start+self.pool_size]

output[:, :, h, w] = np.max(pool_region, axis=(2, 3))

return output

# Example usage

x = np.random.randn(1, 3, 32, 32) # Batch=1, RGB, 32x32

conv = Conv2D(3, 16, kernel_size=3)

pool = MaxPool2D(pool_size=2)

x = conv.forward(x)

print(f"After conv: {x.shape}") # (1, 16, 30, 30)

x = np.maximum(0, x) # ReLU

x = pool.forward(x)

print(f"After pool: {x.shape}") # (1, 16, 15, 15)After conv: (1, 16, 30, 30)

After pool: (1, 16, 15, 15)Architecture Efficiency on ImageNet

ResNet-50 (2015):

- 25M parameters

- 76% top-1 accuracy

- 10ms inference (GPU)

MobileNetV2 (2018):

- 3.5M parameters (7× smaller)

- 72% top-1 accuracy (4% drop)

- 3ms inference (3× faster)

EfficientNet-B0 (2019):

- 5M parameters (5× smaller than ResNet)

- 77% top-1 accuracy (1% higher than ResNet)

- 4ms inference (2.5× faster)

Architecture design matters: EfficientNet achieves better accuracy than ResNet-50 with far fewer parameters.

The Practice of Deep Learning

A Recipe for Training Neural Networks

The Training Loop

\[\theta_{t+1} = \theta_t - \eta \cdot \frac{1}{|B|} \sum_{i \in B} \nabla_\theta \mathcal{L}(f_\theta(x_i), y_i)\]

Karpathy’s Principles

1. Become one with the data Look at your data. Plot it. Understand its distribution, outliers, patterns.

2. Set up end-to-end pipeline Get a simple model training before complexity.

3. Overfit a single batch If you can’t overfit 10 examples, something is broken.

4. Verify loss at initialization Check loss matches expected value (e.g., \(\log(n_{classes})\) for classification).

5. Add complexity gradually Start simple, add one thing at a time.

# The debugging progression

def debug_training():

# Step 1: Overfit one example

single_x = X[0:1]

single_y = y[0:1]

for _ in range(100):

loss = train_step(single_x, single_y)

assert loss < 0.01, "Can't overfit single"

# Step 2: Overfit small batch

batch_x = X[0:10]

batch_y = y[0:10]

for _ in range(500):

loss = train_step(batch_x, batch_y)

assert loss < 0.1, "Can't overfit batch"

# Step 3: Check with real data

# Only now move to full dataset

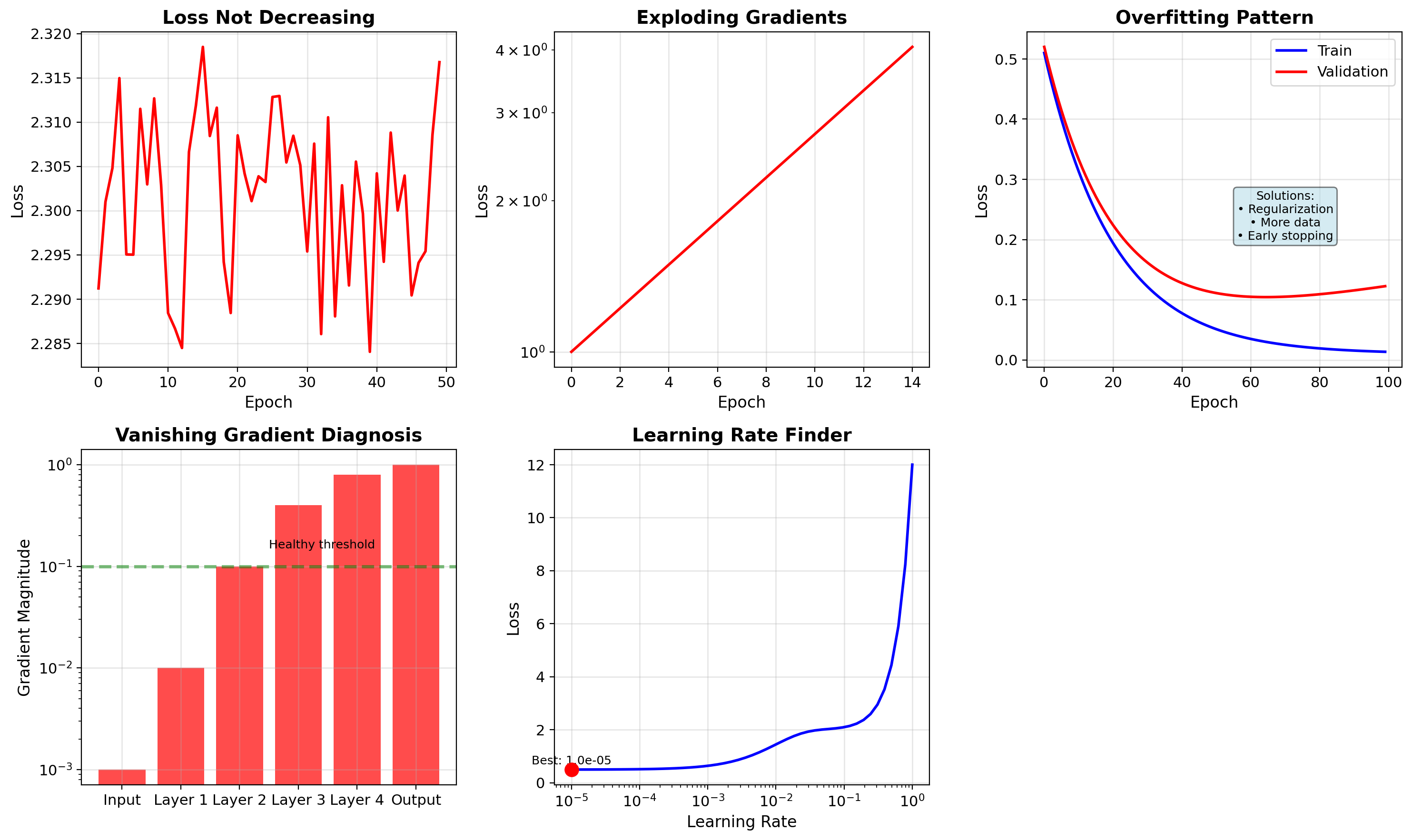

return "Ready for full training"Debugging Deep Learning

Medical Imaging: High Accuracy Hides Dataset Problems

Setup:

- Train pneumonia detector on chest X-rays

- Dataset: 10,000 images from Hospital A

- Training accuracy: 95%

- Validation accuracy: 94%

- Model looks ready to deploy

Deployment at Hospital B:

- Accuracy drops to 72%

- False negatives increase 3×

What went wrong:

Hospital A used one X-ray machine model with specific image characteristics. Hospital B used different equipment. Model learned machine artifacts, not disease patterns.

Example artifacts learned:

- Brightness/contrast settings

- Image resolution differences

- Metal markers in specific corners

- Patient positioning conventions

Shortcut learning: Standard debugging looked fine:

- Training loss decreasing smoothly

- No overfitting (train/val gap small)

- High validation accuracy

- Good precision/recall on test set

Problem only appeared on different hospital equipment. Models exploit spurious correlations (disease + specific machine) as shortcuts instead of learning actual medical patterns.

Computational Realities

What this means for this course:

CPU (your laptop):

- Sufficient for: Most course assignments including smaller CNNs

- Time scale: Minutes per epoch on MNIST, tens of minutes on CIFAR-10

- Cost: Free

GPU (Colab/Kaggle free tier):

- Useful for: Faster iteration, larger architectures, final project

- Time scale: Seconds per epoch

- Cost: Free (with session limits)

Multi-GPU (cloud):

- Rarely needed: Only for very large-scale experiments

- Cost: $1-3 per hour

Course approach: CPU is viable for most work. GPU accelerates but isn’t required.

Systematic Experimentation

Experiment tracking example

# Tracking experiments

experiment_config = {

'model': 'resnet18',

'dataset': 'cifar10',

'batch_size': 128,

'lr': 0.1,

'epochs': 100,

'seed': 42,

'timestamp': '2025-01-15-14:30'

}

# Always set seeds for reproducibility

def set_all_seeds(seed=42):

np.random.seed(seed)

# torch.manual_seed(seed)

# torch.cuda.manual_seed_all(seed)

# random.seed(seed)

# Log everything

def log_metrics(epoch, train_loss, val_loss, val_acc):

metrics = {

'epoch': epoch,

'train_loss': train_loss,

'val_loss': val_loss,

'val_acc': val_acc,

'lr': get_current_lr(),

'timestamp': time.time()

}

# Write to file, tensorboard, wandb, etc.

return metrics

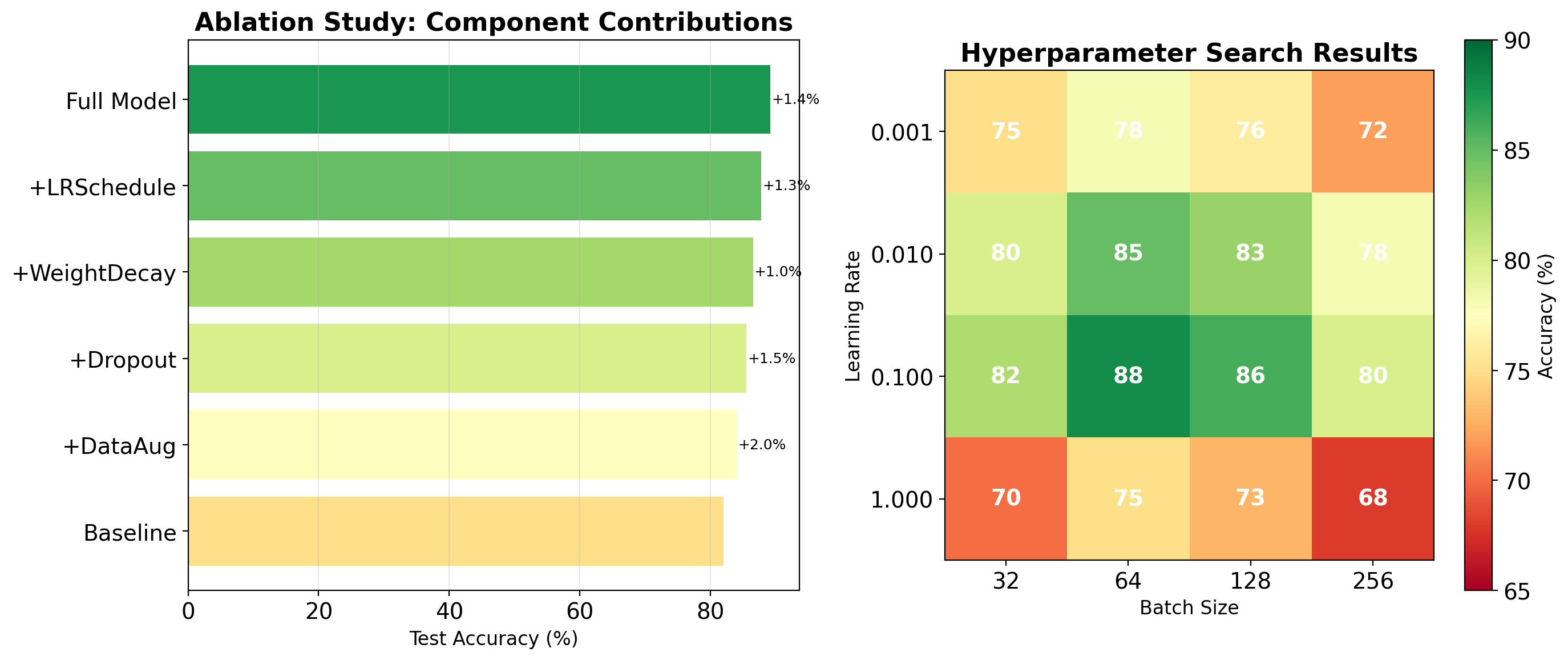

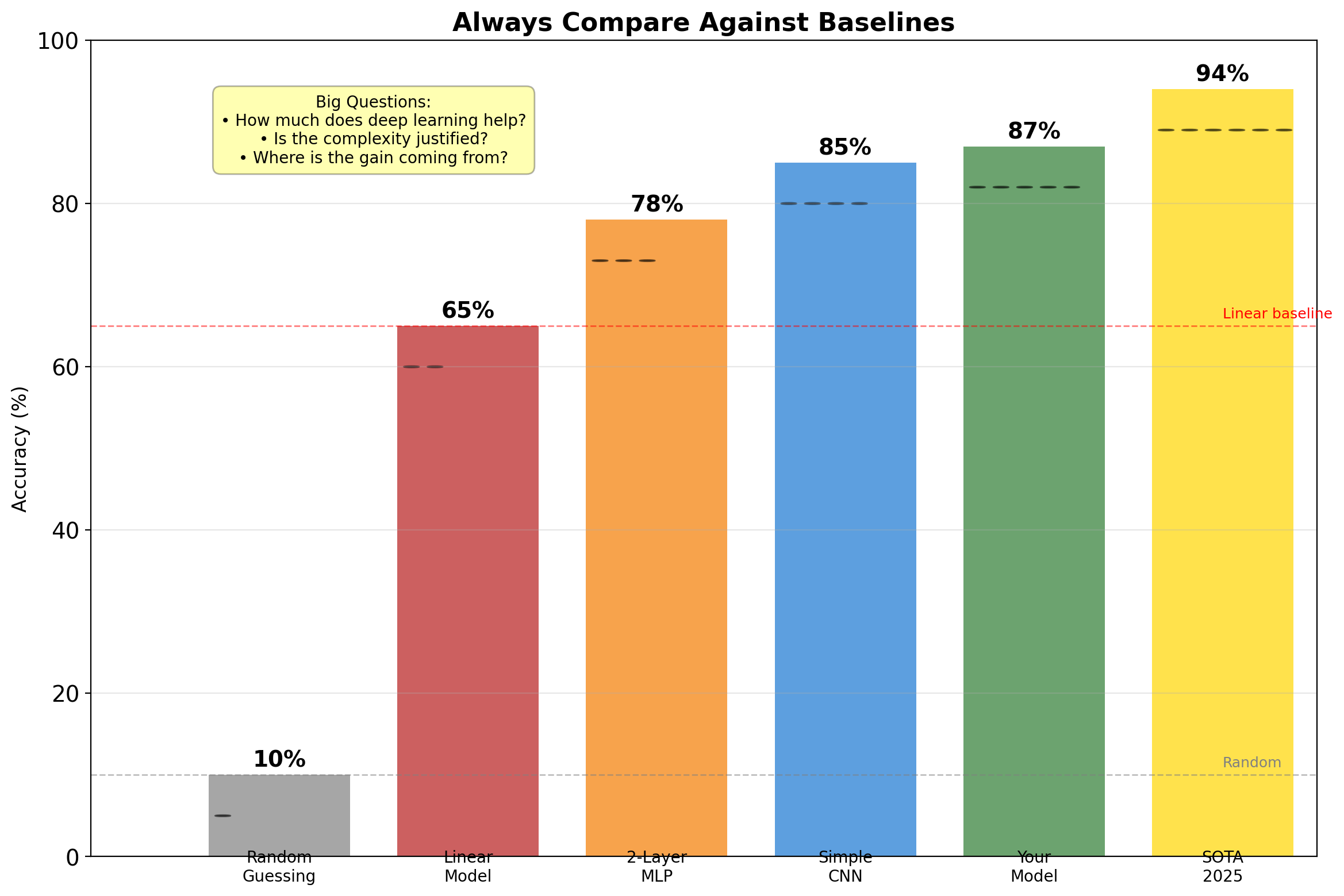

Always Establish Baselines Before Claiming Improvement

Current Frontiers & Course Roadmap

Course Architecture: Statistical to Neural

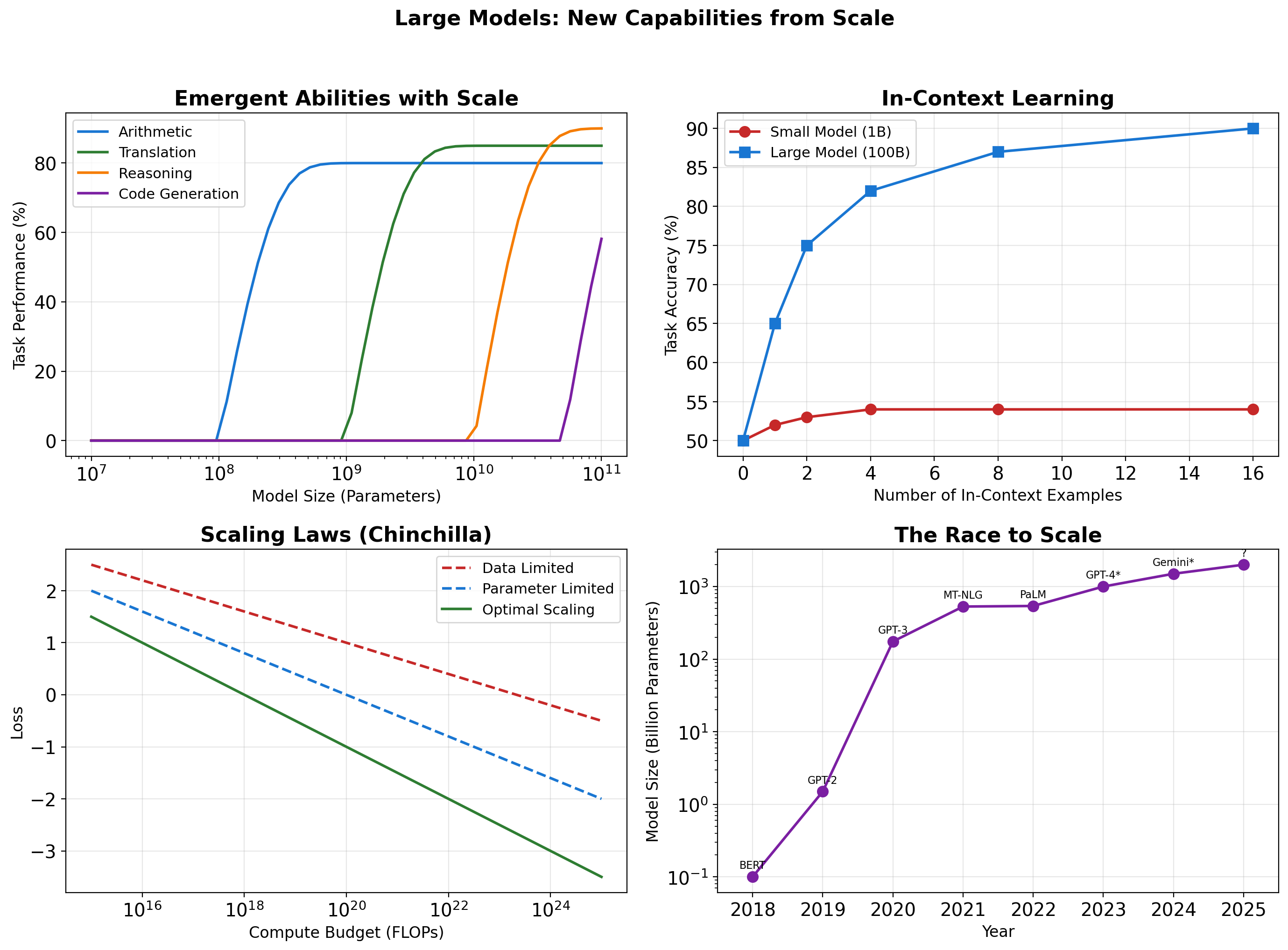

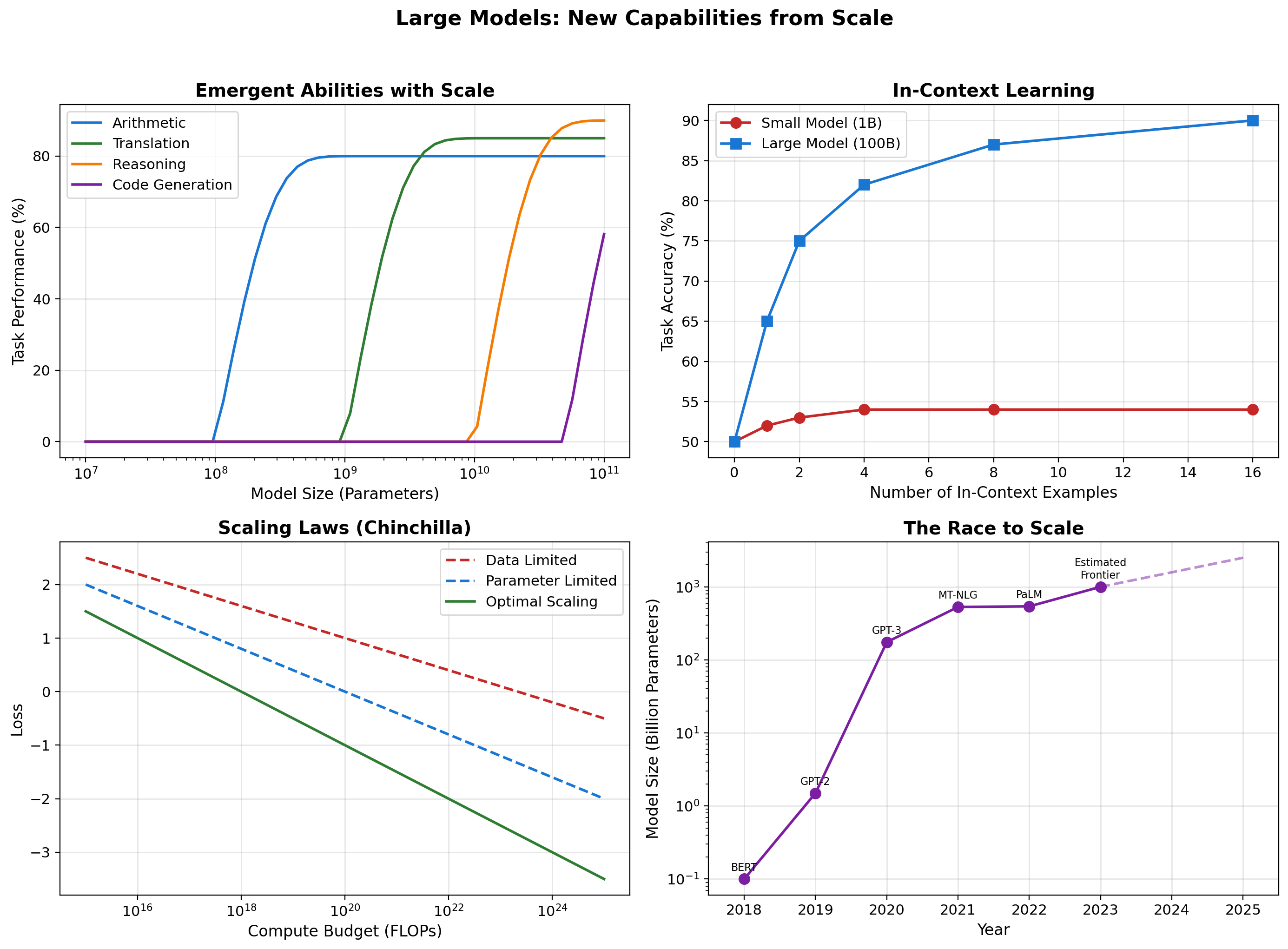

Scaling Laws and Emergent Capabilities

What these scales cost:

GPT-2 (1.5B params, 2019):

- Training: ~$50K compute, weeks on multi-GPU

- Inference: Runs on laptop CPU

GPT-3 (175B params, 2020):

- Training: ~$5M compute, months on cluster

- Inference: Requires GPU server

PaLM (540B params, 2022):

- Training: ~$10M+ compute, specialized infrastructure

- Inference: Multi-GPU required

Scale is not just about bigger numbers - it’s about fundamentally different resource requirements.

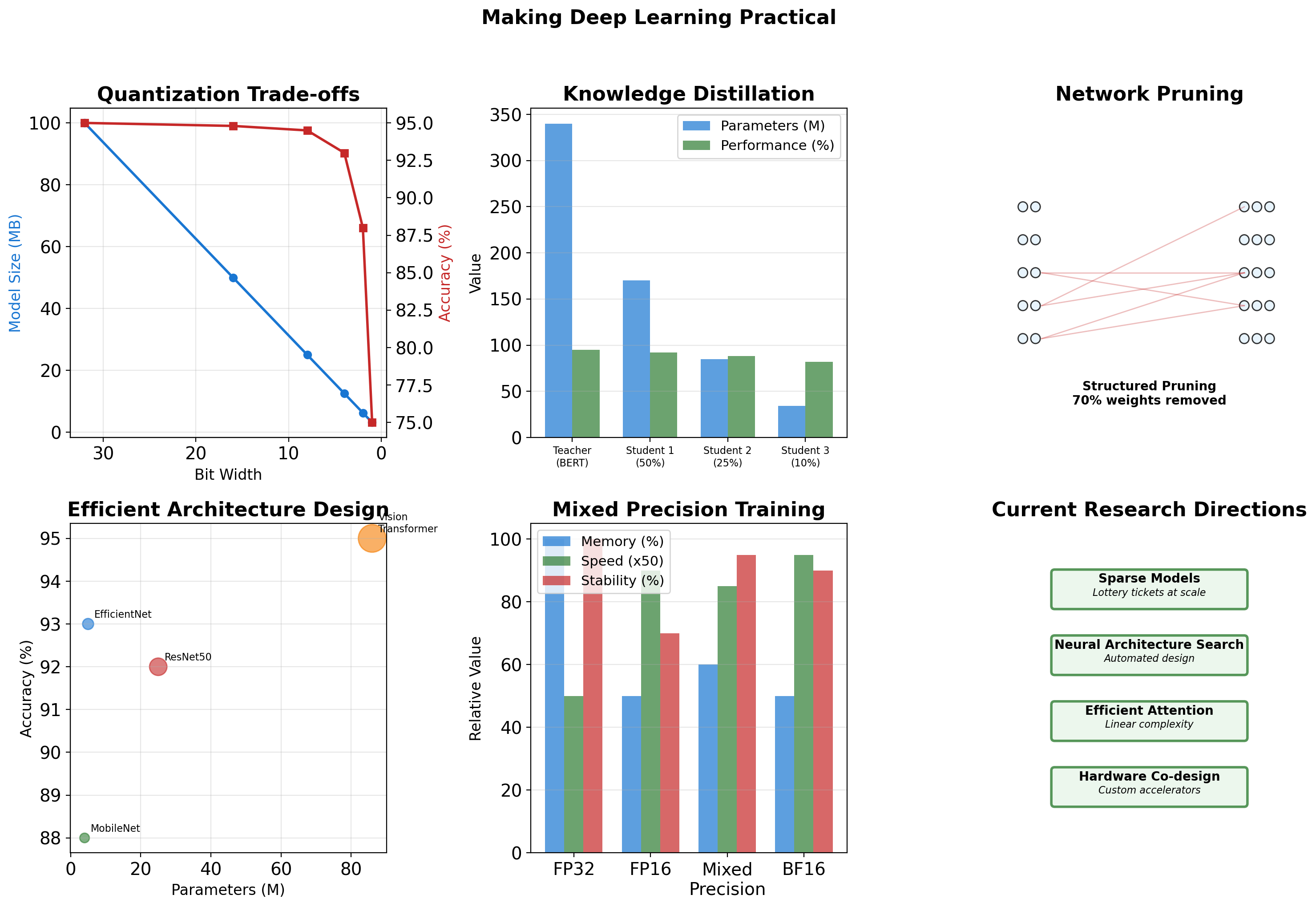

Model Compression and Acceleration

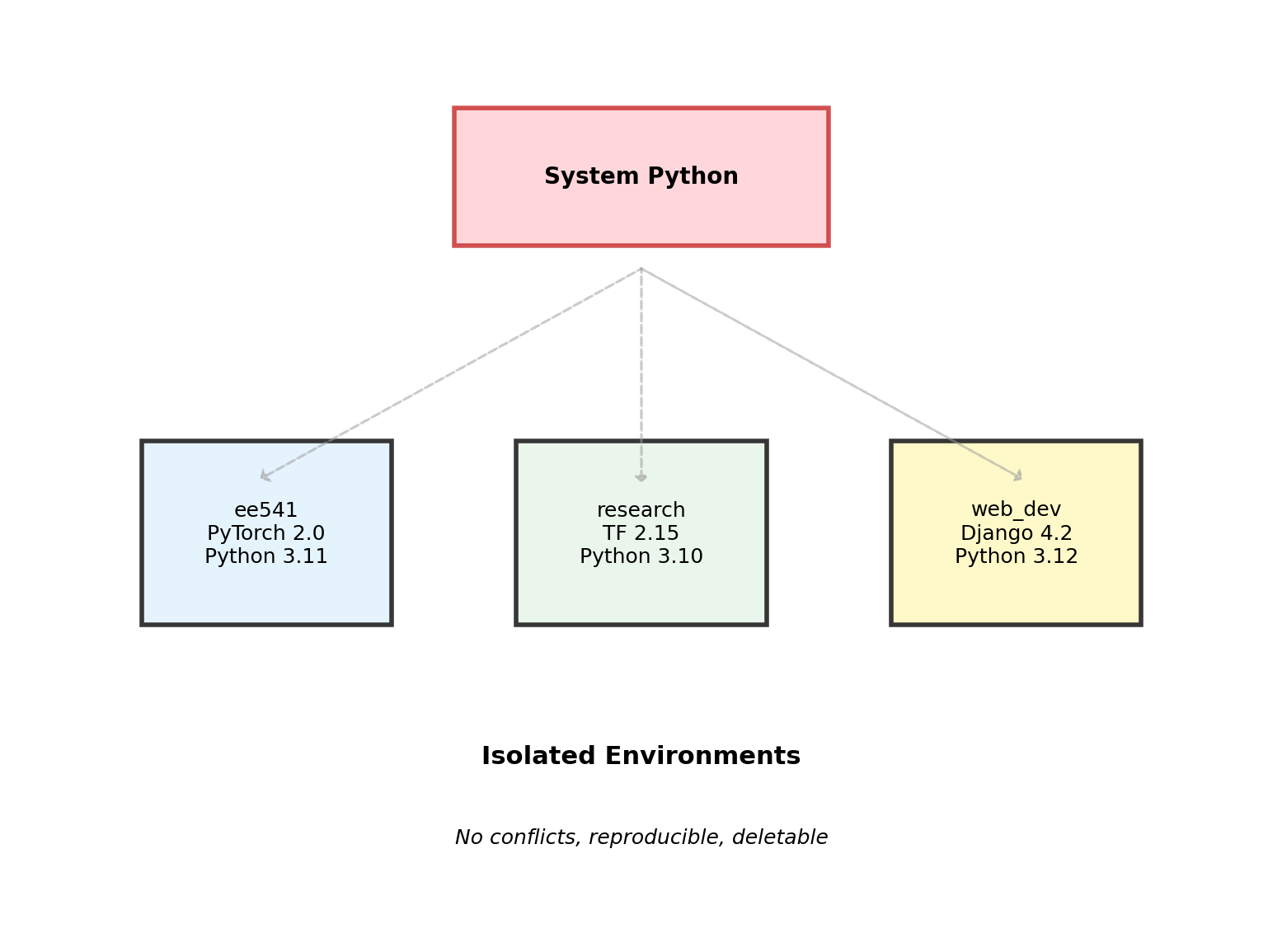

Python Environment Setup

Environment Management: Why It Matters

Dependency Conflicts

# System Python - Don't do this

python install torch

# Error: requires numpy>=1.19

pip install numpy==1.20

# Breaks: opencv requires numpy==1.18Conflicts are inevitable. Each project needs:

- Specific Python version

- Specific package versions

- Isolated from system Python

Virtual Environments

Conda: Package and Environment Management

Installation

# Download Miniconda (minimal) or Anaconda (full)

# miniconda.anaconda.com

# After installation, verify:

conda --version

conda info

# Update conda itself

conda update -n base condaCreate Course Environment

Why Conda for Deep Learning

Binary package management

- Precompiled CUDA libraries

- Optimized BLAS/LAPACK

- No compilation required

Cross-platform

- Same commands on Windows/Mac/Linux

- Handles system dependencies

Channel system

conda-forge: Community packagespytorch: Official PyTorch buildsnvidia: CUDA toolkit

Environment files

- Share exact environment

environment.ymlfor reproducibility

Essential Package Installation

# Activate your environment first

conda activate ee541

# Core scientific stack

conda install numpy scipy matplotlib pandas

# Jupyter for notebooks

conda install jupyter ipykernel

# Register kernel for Jupyter

python -m ipykernel install --user --name ee541 --display-name "Python (ee541)"

# PyTorch - SELECT BASED ON YOUR SYSTEM

# CPU only

conda install pytorch torchvision torchaudio cpuonly -c pytorch

# CUDA 11.8 (NVIDIA GPU)

conda install pytorch torchvision torchaudio pytorch-cuda=11.8 -c pytorch -c nvidia

# Mac M1/M2/M3 (Metal Performance Shaders)

conda install pytorch torchvision torchaudio -c pytorch

# Additional ML tools

conda install scikit-learn

conda install -c conda-forge tensorboardGPU Configuration Check

- NVIDIA: Check CUDA version with

nvidia-smi - AMD: ROCm support limited, use CPU fallback

- Mac (MPS): Automatic detection in PyTorch 1.12+

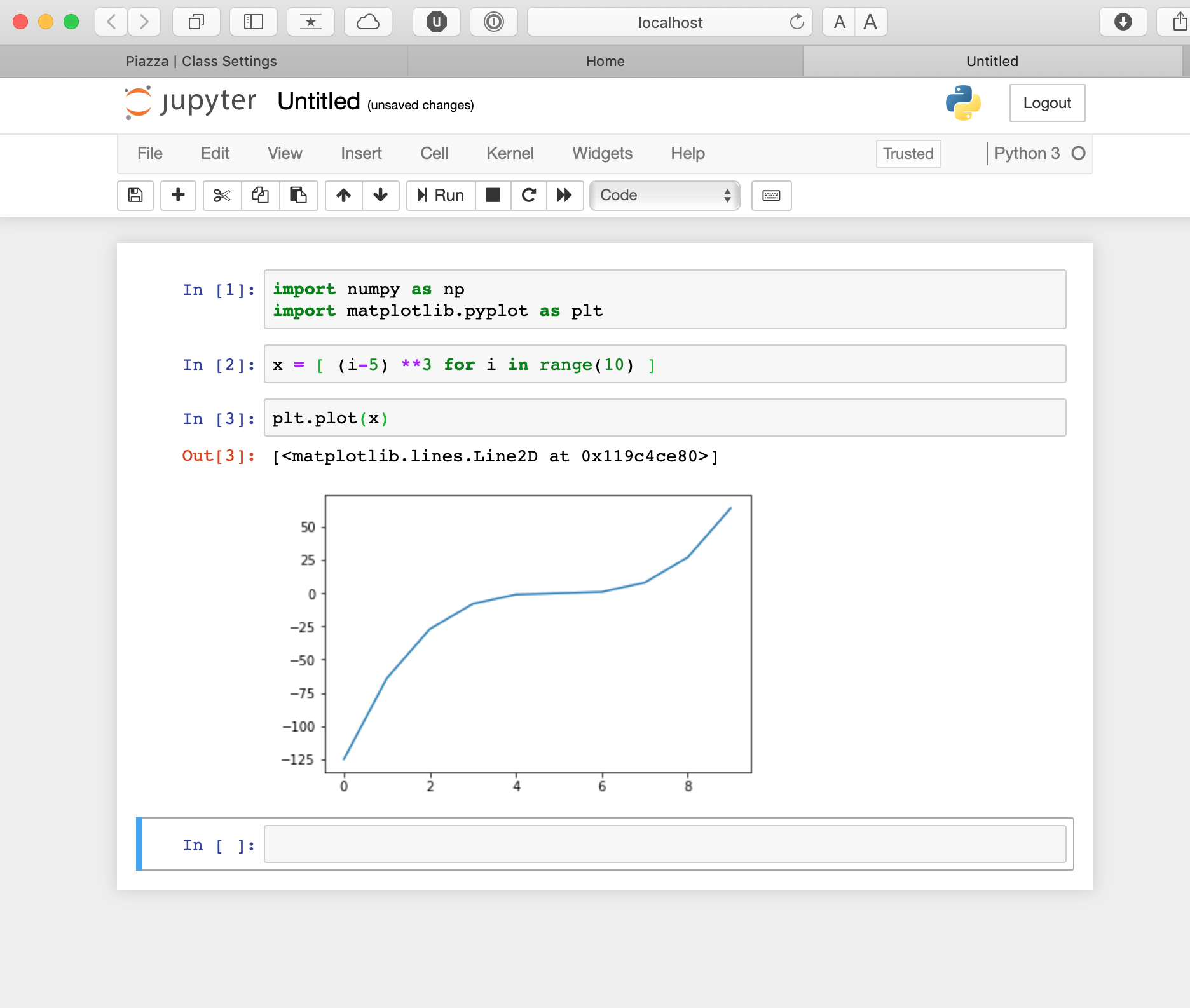

Jupyter Notebooks: Interactive Development

Starting Jupyter

# From terminal with environment active

(ee541) $ jupyter notebook

# Opens browser at localhost:8888

# Navigate to your work directoryNotebook Structure

- Cells: Code or Markdown

- Kernel: Python process executing code

- State: Variables persist between cells

Key Shortcuts

Shift+Enter: Run cell, move to nextCtrl+Enter: Run cell, stayEsc: Command modeEnter: Edit modeA/B: Insert cell above/below

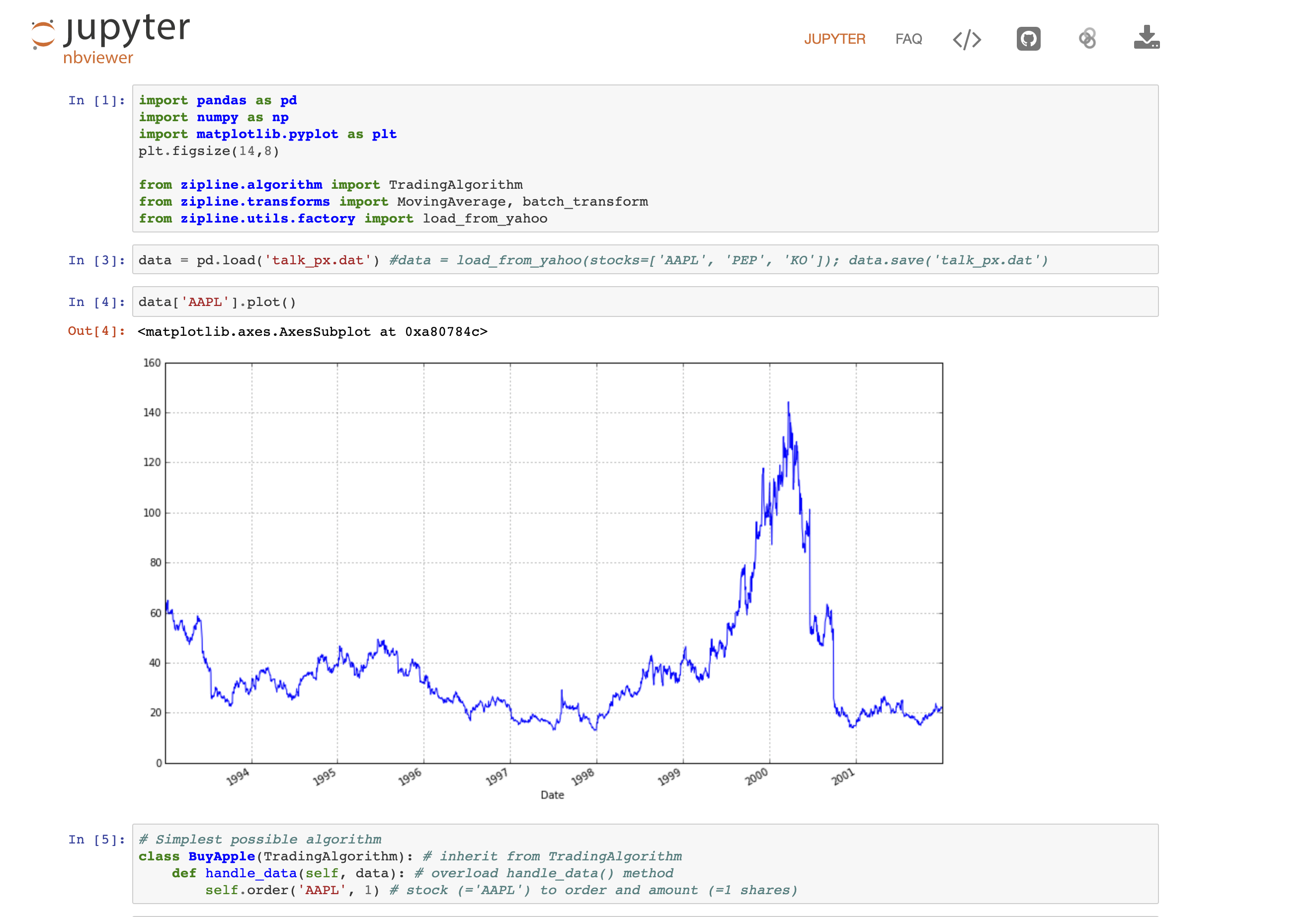

Real-World Example: Trading Algorithm

Project Management

Version Control

Verifying Your Environment

import sys

import platform

print(f"Python: {sys.version}")

print(f"Platform: {platform.platform()}")

packages = {

'numpy': None,

'torch': None,

'torchvision': None,

'matplotlib': None,

'jupyter': None,

'sklearn': 'scikit-learn'

}

for import_name, pip_name in packages.items():

try:

module = __import__(import_name)

version = getattr(module, '__version__', 'installed')

print(f"✓ {import_name}: {version}")

# Special check for PyTorch GPU

if import_name == 'torch':

import torch

if torch.cuda.is_available():

print(f" GPU: CUDA ({torch.version.cuda})")

print(f" Device: {torch.cuda.get_device_name(0)}")

elif torch.backends.mps.is_available():

print(f" GPU: MPS (Mac)")

else:

print(f" GPU: Not available")

except ImportError:

package = pip_name or import_name

print(f"✗ {import_name}: Not installed")

print(f" Install with: conda install {package}")Python: 3.11.8 | packaged by conda-forge | (main, Feb 16 2024, 20:49:36) [Clang 16.0.6 ]

Platform: macOS-26.2-arm64-arm-64bit

✓ numpy: 1.26.4

✓ torch: 2.5.1

GPU: MPS (Mac)

✓ torchvision: 0.20.1

✓ matplotlib: 3.10.6

✓ jupyter: installed

✓ sklearn: 1.6.1Environment Management Commands

Conda Essentials

Package Management

PyTorch Demo

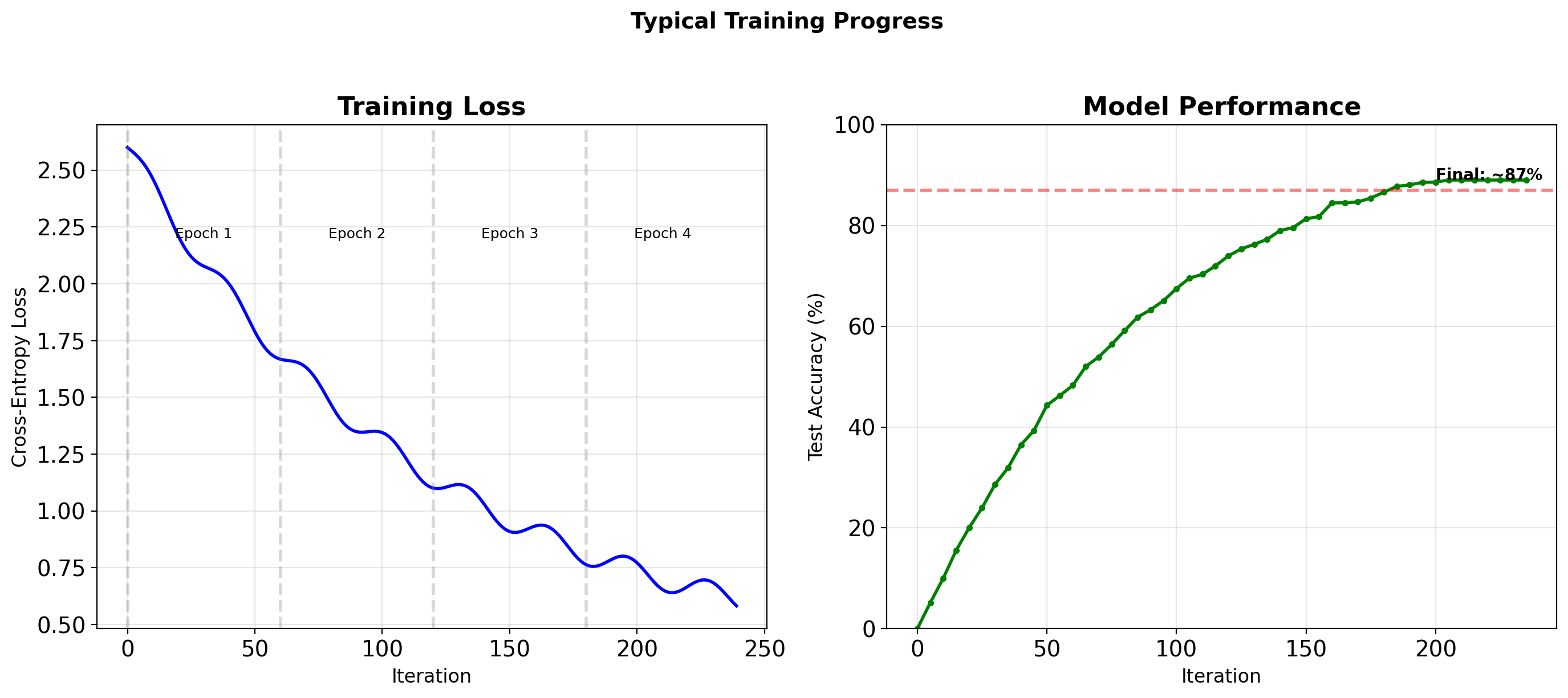

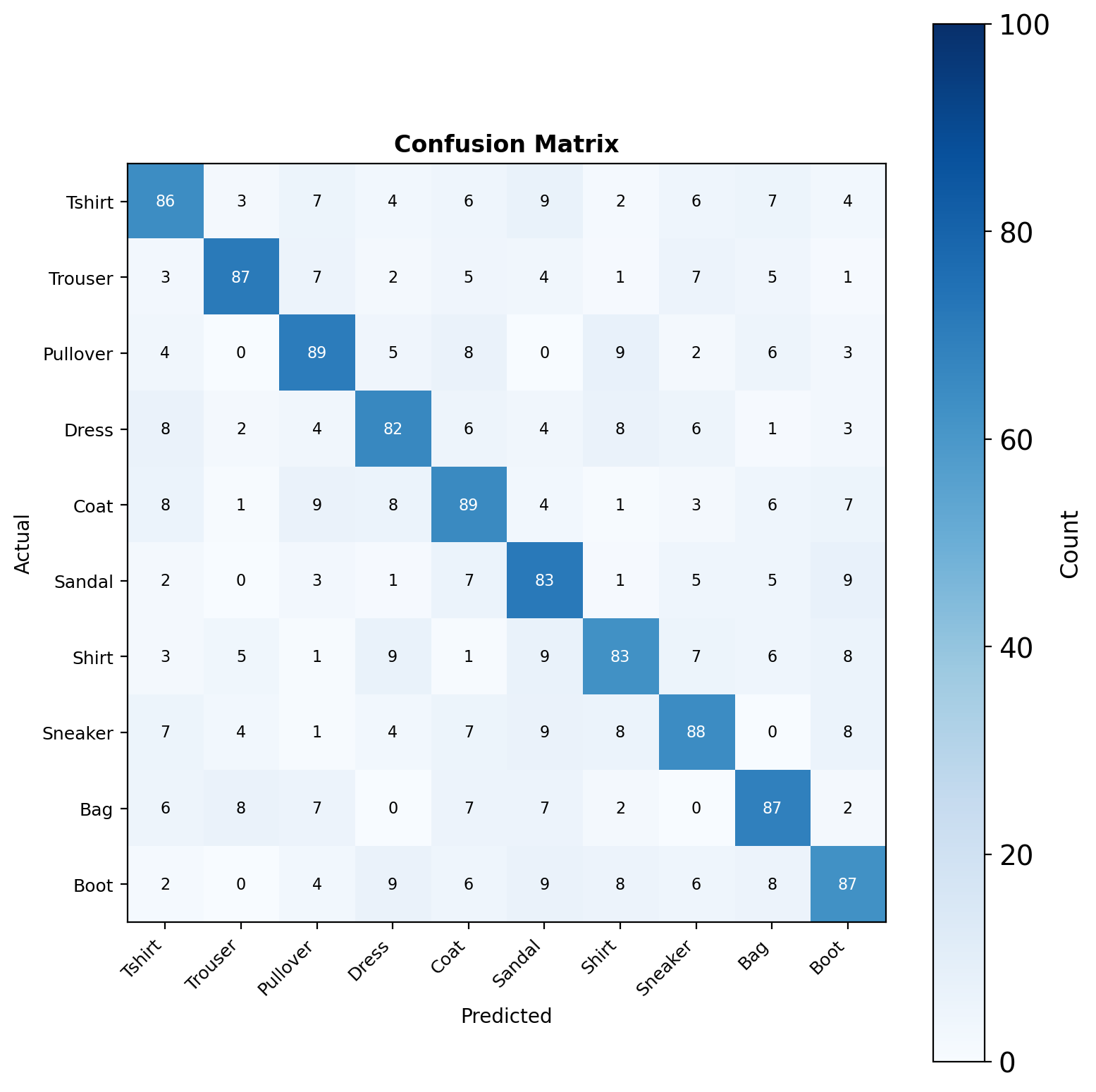

Fashion-MNIST: 87% Accuracy in Four Epochs

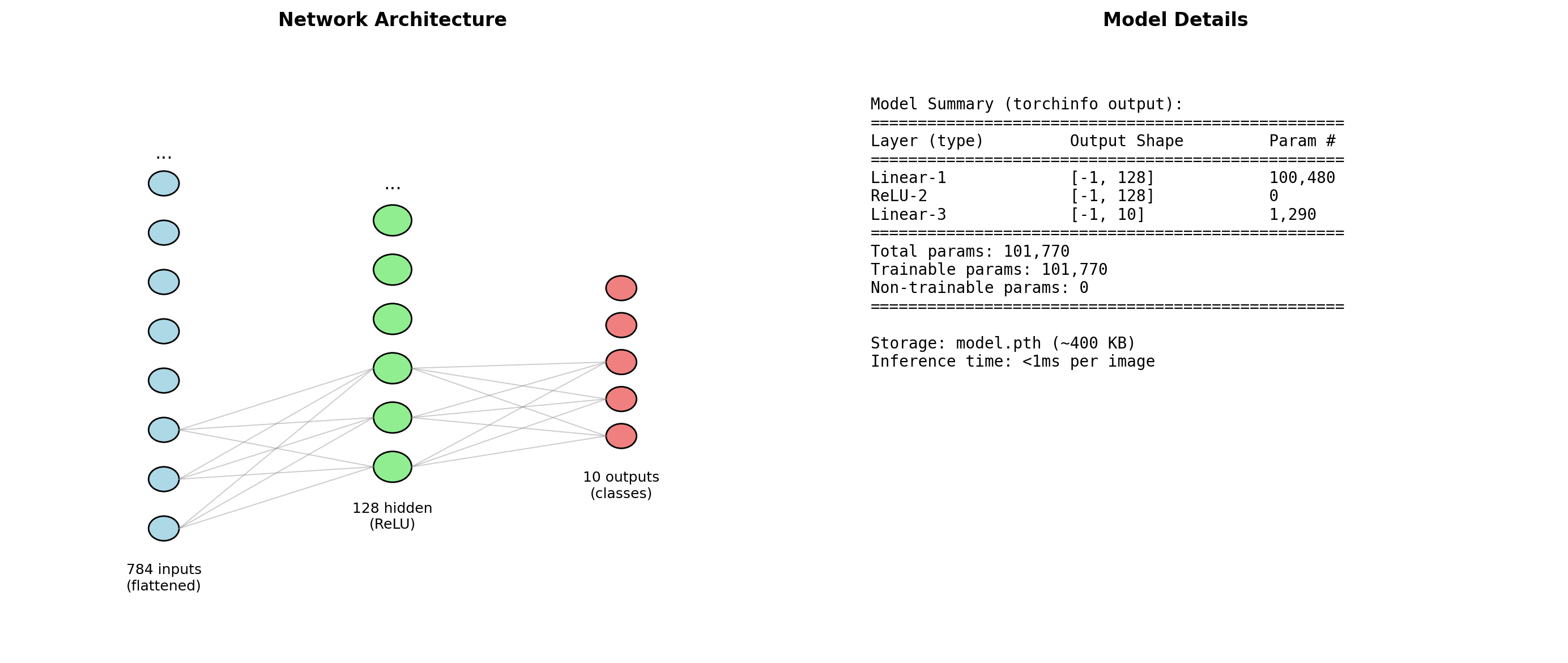

What We’re Building

Task: Classify clothing items into 10 categories

Architecture: Simple 2-layer network

- Input: 28×28 grayscale images (784 pixels)

- Hidden: 128 neurons with ReLU

- Output: 10 classes (softmax)

Training: 4 epochs, Adam optimizer

Files:

1-fashion-mnist.ipynb: Dataset exploration2-minimal-pytorch.ipynb: Core training loop3-feature-visualization.ipynb: TensorBoard monitoring

T-shirt

Trouser

Pullover

Dress

Coat

Sandal

Shirt

Sneaker

Bag

Boot

Core Training Loop Structure

# Minimal.ipynb - Key components

# 1. Data Loading

train_loader = DataLoader(train_set, batch_size=100, shuffle=True)

test_loader = DataLoader(test_set, batch_size=100, shuffle=False)

# 2. Model Definition

class Net(nn.Module):

def __init__(self):

super(Net, self).__init__()

self.hidden = nn.Linear(784, 128)

self.output = nn.Linear(128, 10)

def forward(self, x):

x = F.relu(self.hidden(x))

return self.output(x)

# 3. Training Loop

for epoch in range(num_epochs):

for images, labels in train_loader:

# Forward pass

outputs = model(images.view(-1, 784))

loss = loss_func(outputs, labels)

# Backward pass

optimizer.zero_grad()

loss.backward()

optimizer.step()Training Performance Benchmarks

Complete training in ~5 minutes on CPU, <1 minute on GPU

Training Dynamics

Observations:

- Rapid initial learning (first epoch)

- Diminishing returns with more training

- Test accuracy plateaus around 87% for this simple model

TensorBoard Visualization

Launch TensorBoard

Available Visualizations

- Scalars: Loss, accuracy over time

- Images: Sample predictions

- Graph: Network architecture

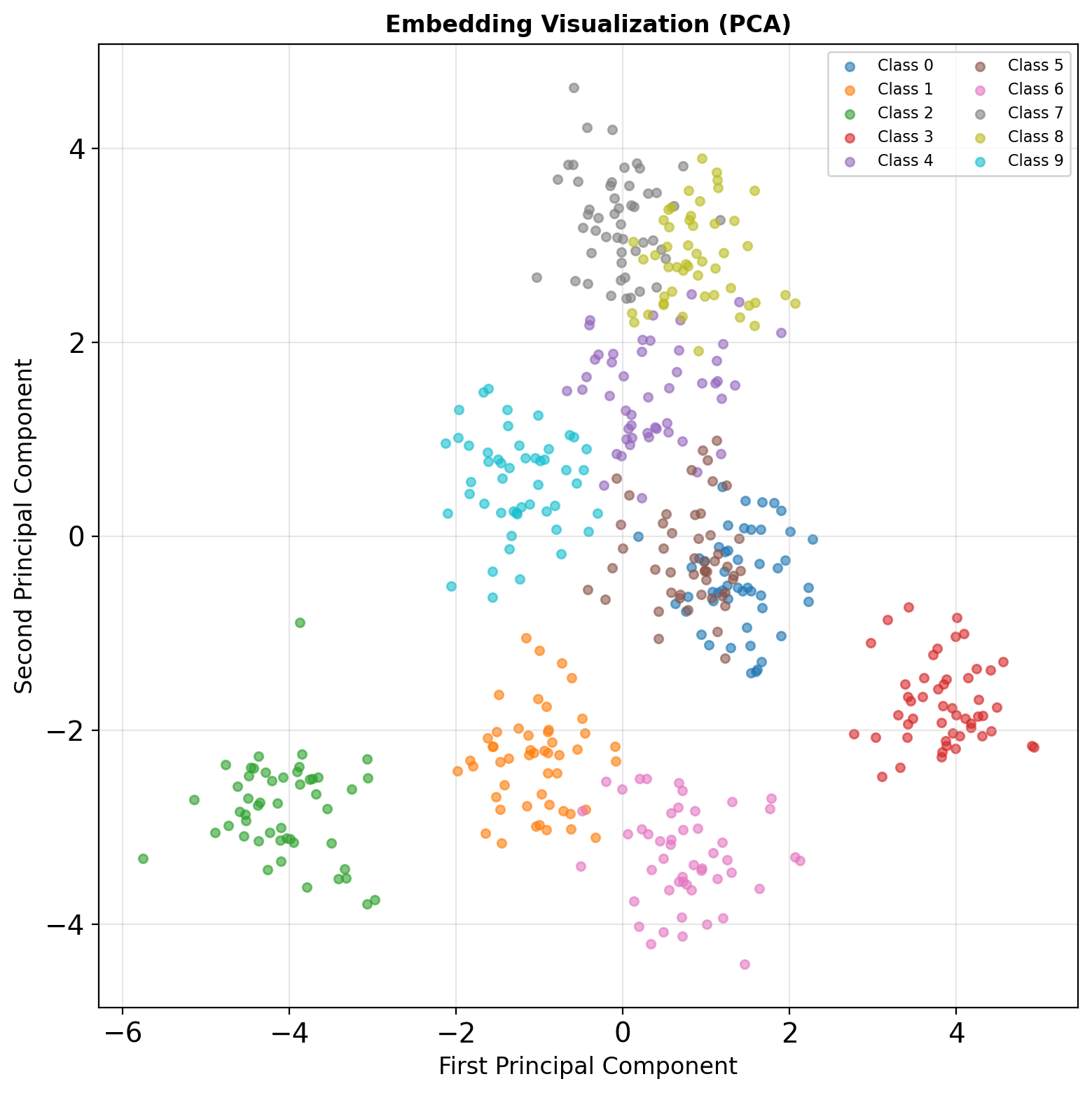

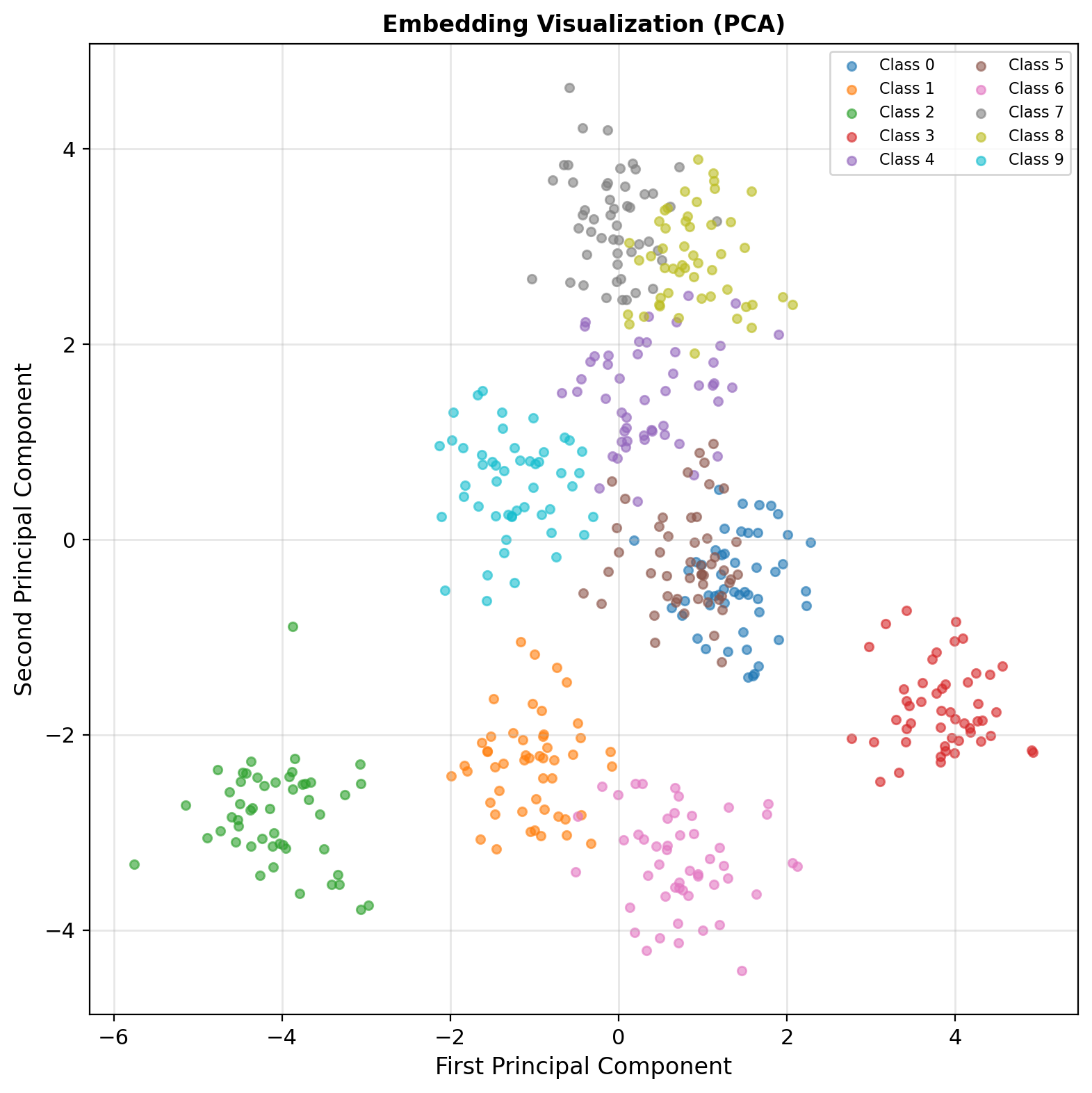

- Embeddings: Feature space (PCA/t-SNE)

- Histograms: Weight distributions

Embedding Insight: Classes form distinct clusters in feature space

Model Architecture Inspection

87% Accuracy Achieved with Simple Architecture

Implementation Results

- Model: 2-layer MLP with 128 hidden units

- Performance: 87% test accuracy after 4 epochs

- Training time: ~2 minutes on CPU

- Bottom line: Simple architectures work well for Fashion-MNIST

Not Addressed (Future Topics)

- Overfitting analysis: No train/val split comparison

- Hyperparameter tuning: Fixed learning rate, no grid search

- Architecture search: Only tried one configuration

- Regularization: No dropout, weight decay, or data augmentation

- Optimizer exploration: Only tried Adam, not SGD variants or AdamW

Main Files

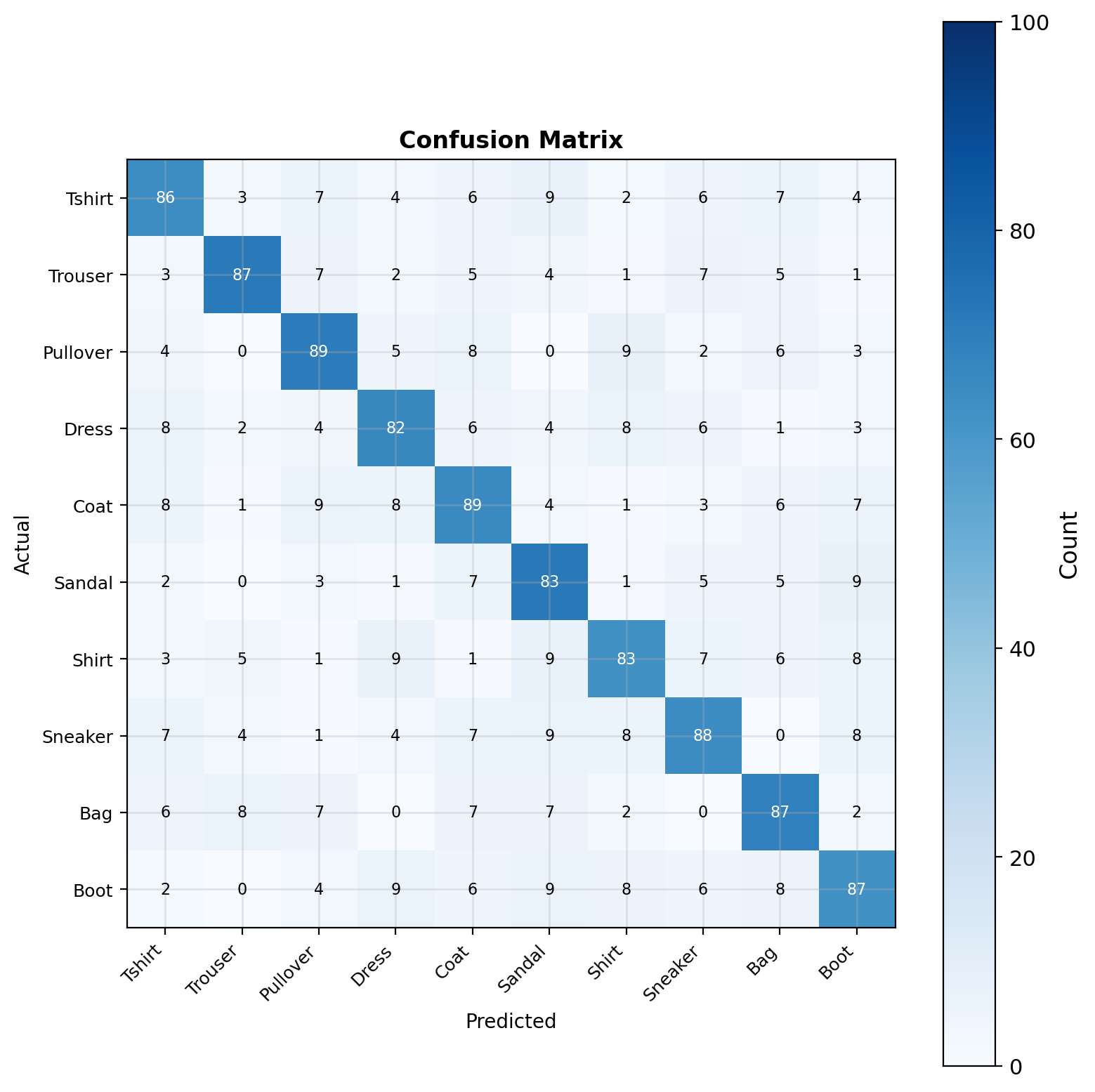

Common Confusions: Shirt ↔︎ T-shirt, Pullover ↔︎ Coat

Python and NumPy for Neural Networks

Next week: Array operations and automatic differentiation