Python Fundamentals

EE 541 - Unit 2

Spring 2026

Outline

Python Internals

- Everything is an object with type and refcount

- Variables as labels, not containers

- Dynamic typing costs

- List over-allocation, dict hash tables

- Mutable defaults trap

- First-class functions, LEGB scope

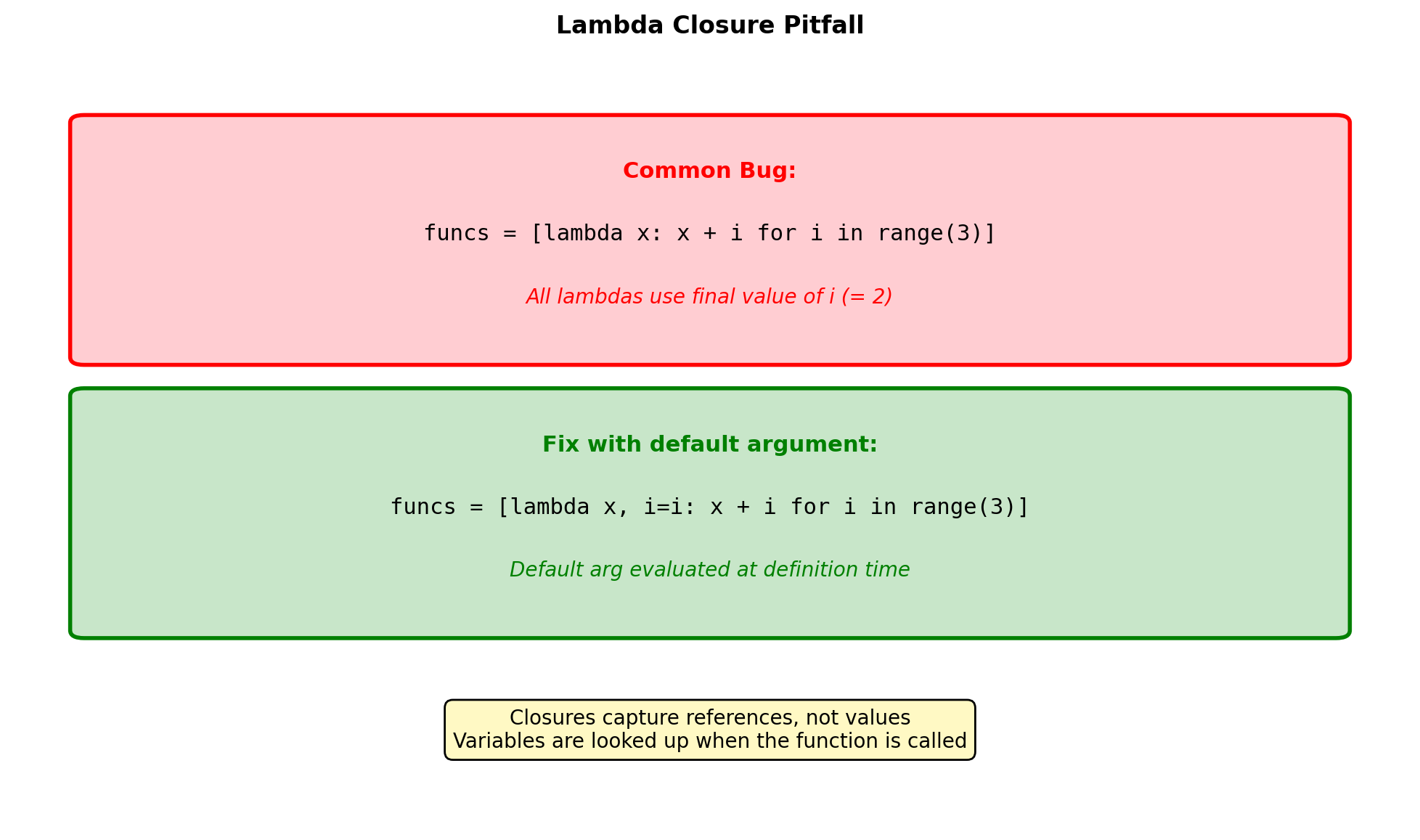

- Closures and captured state

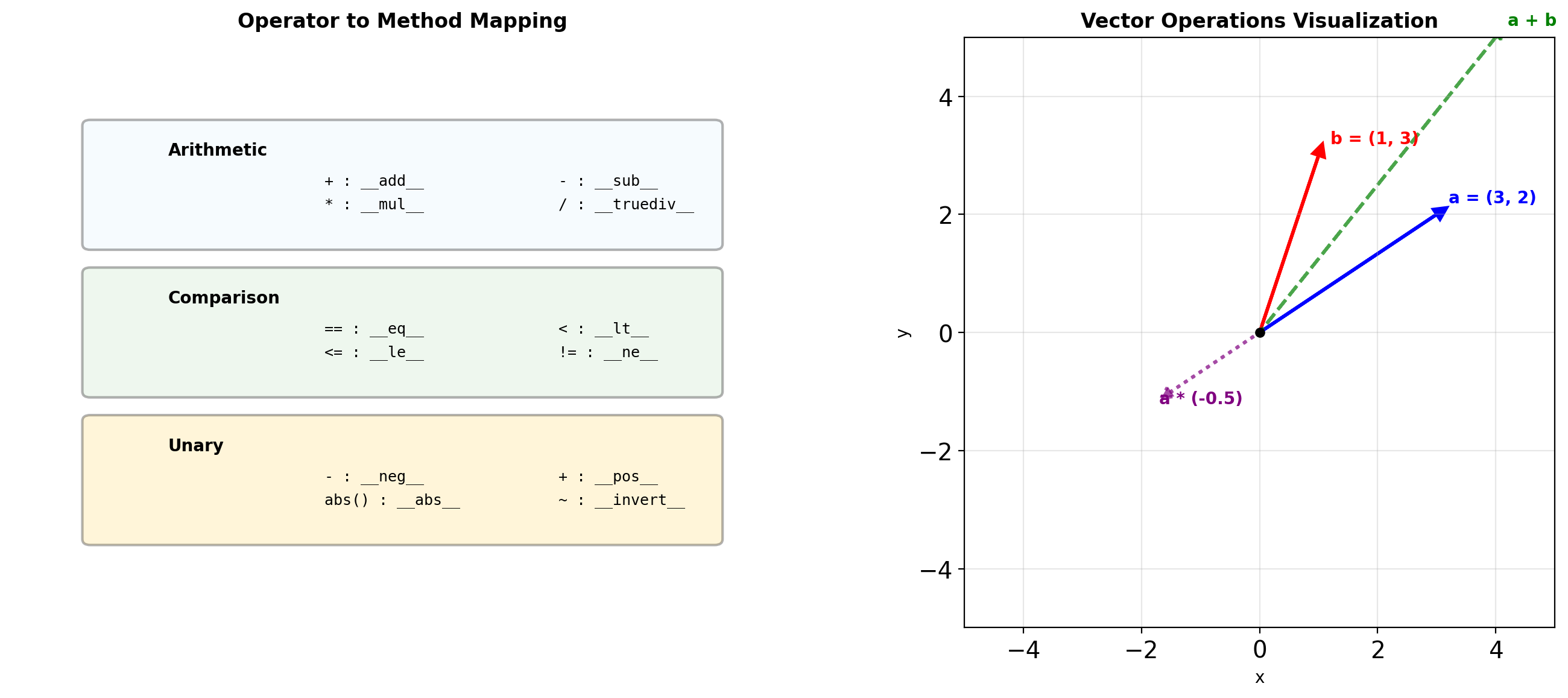

- Operator overloading via dunder methods

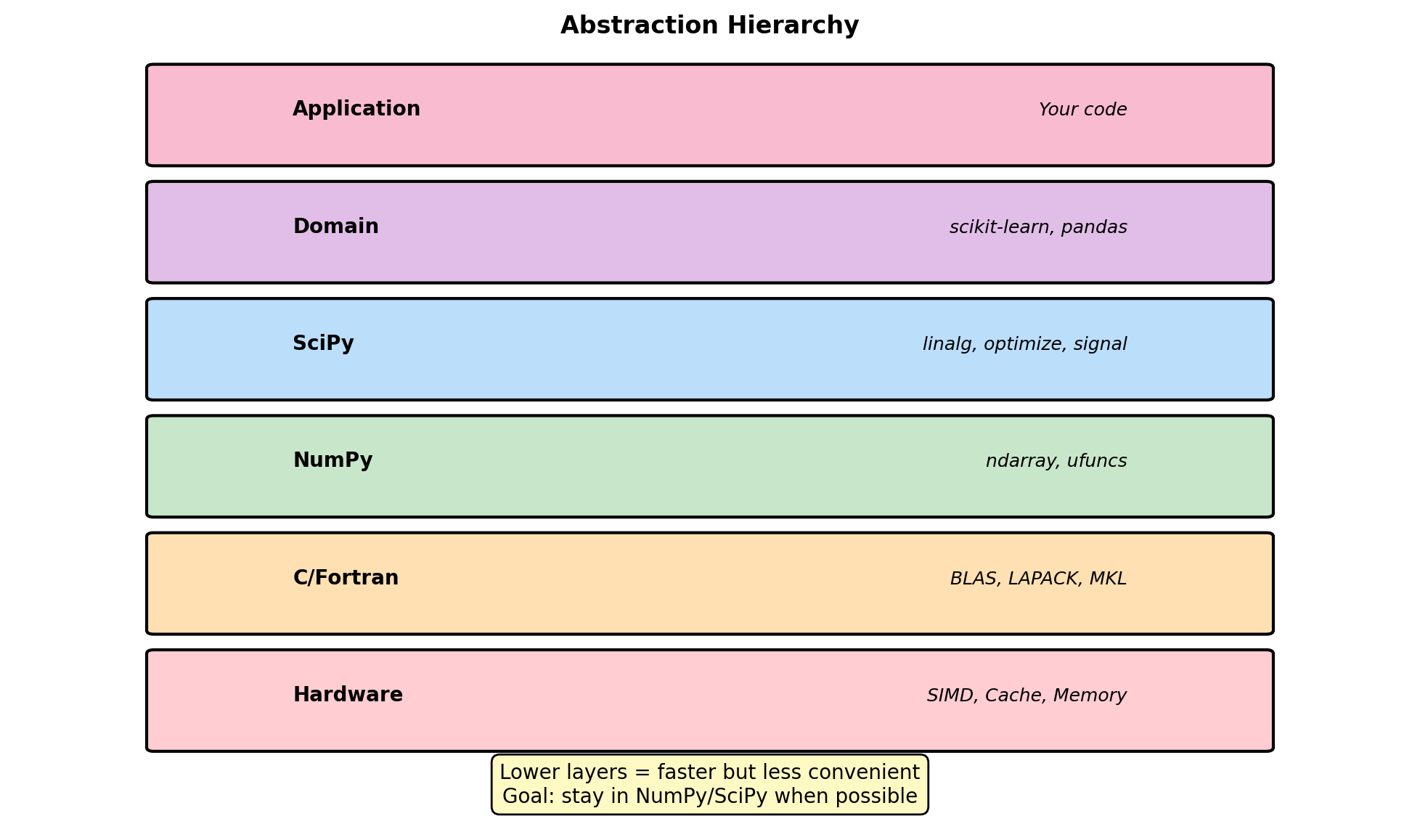

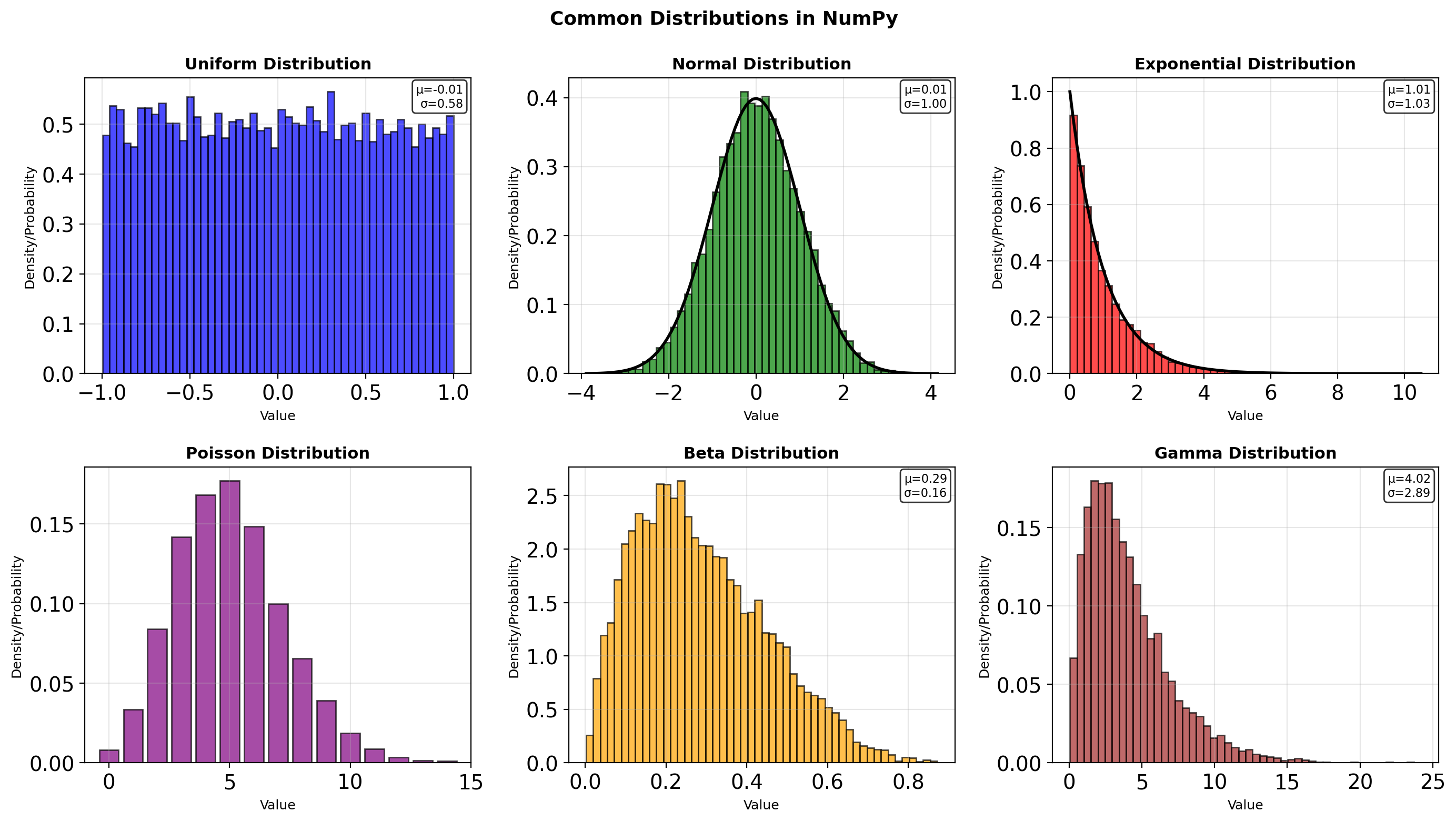

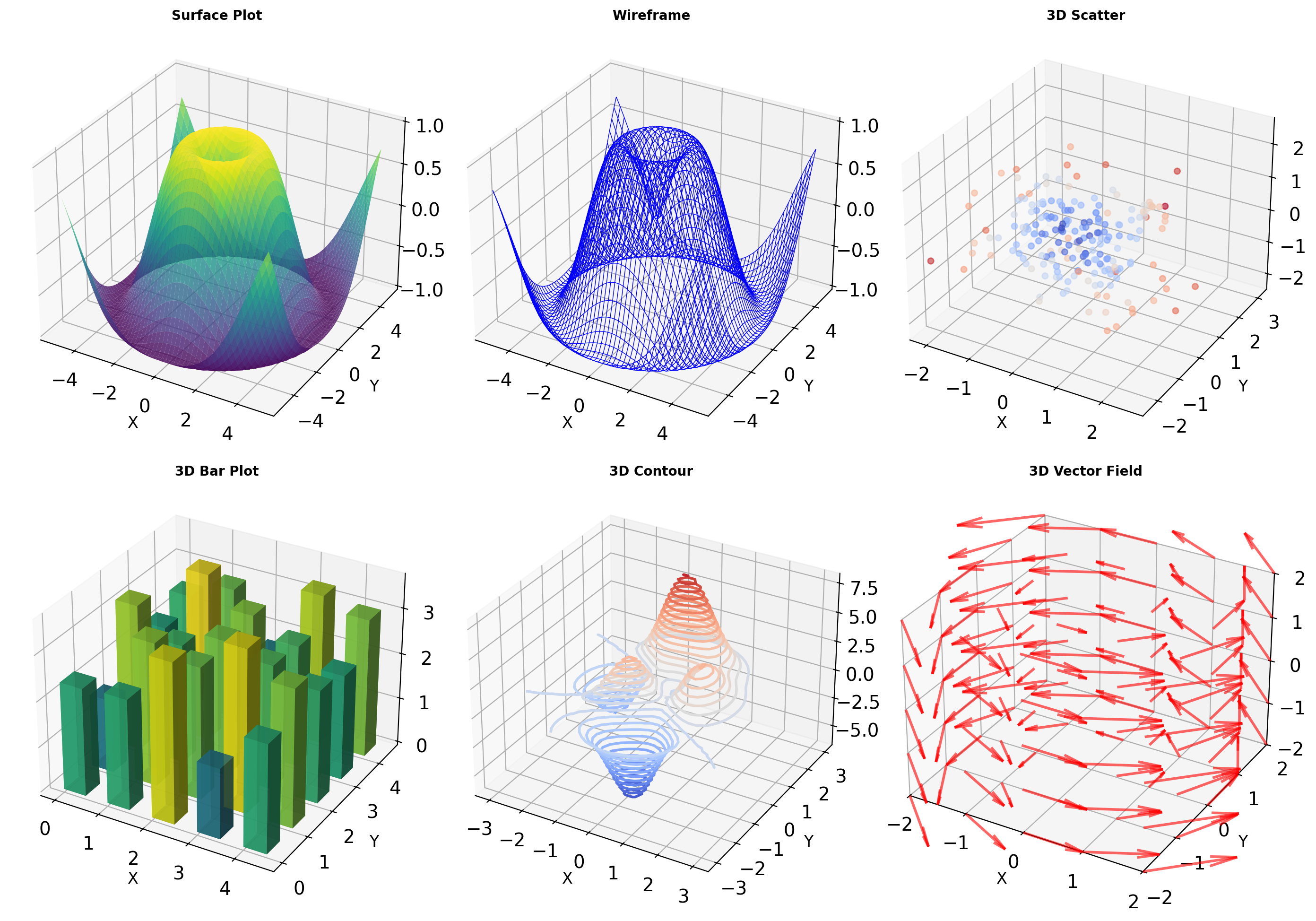

Scientific Computing

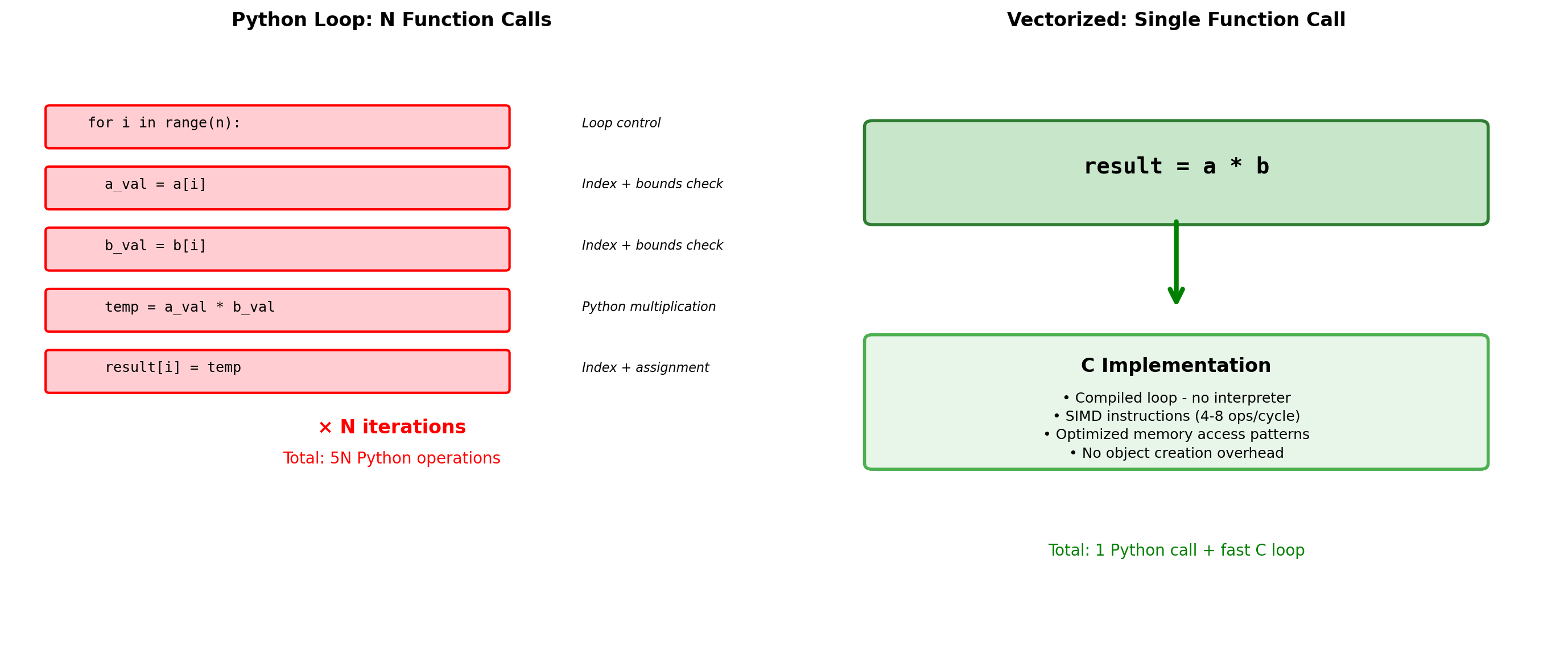

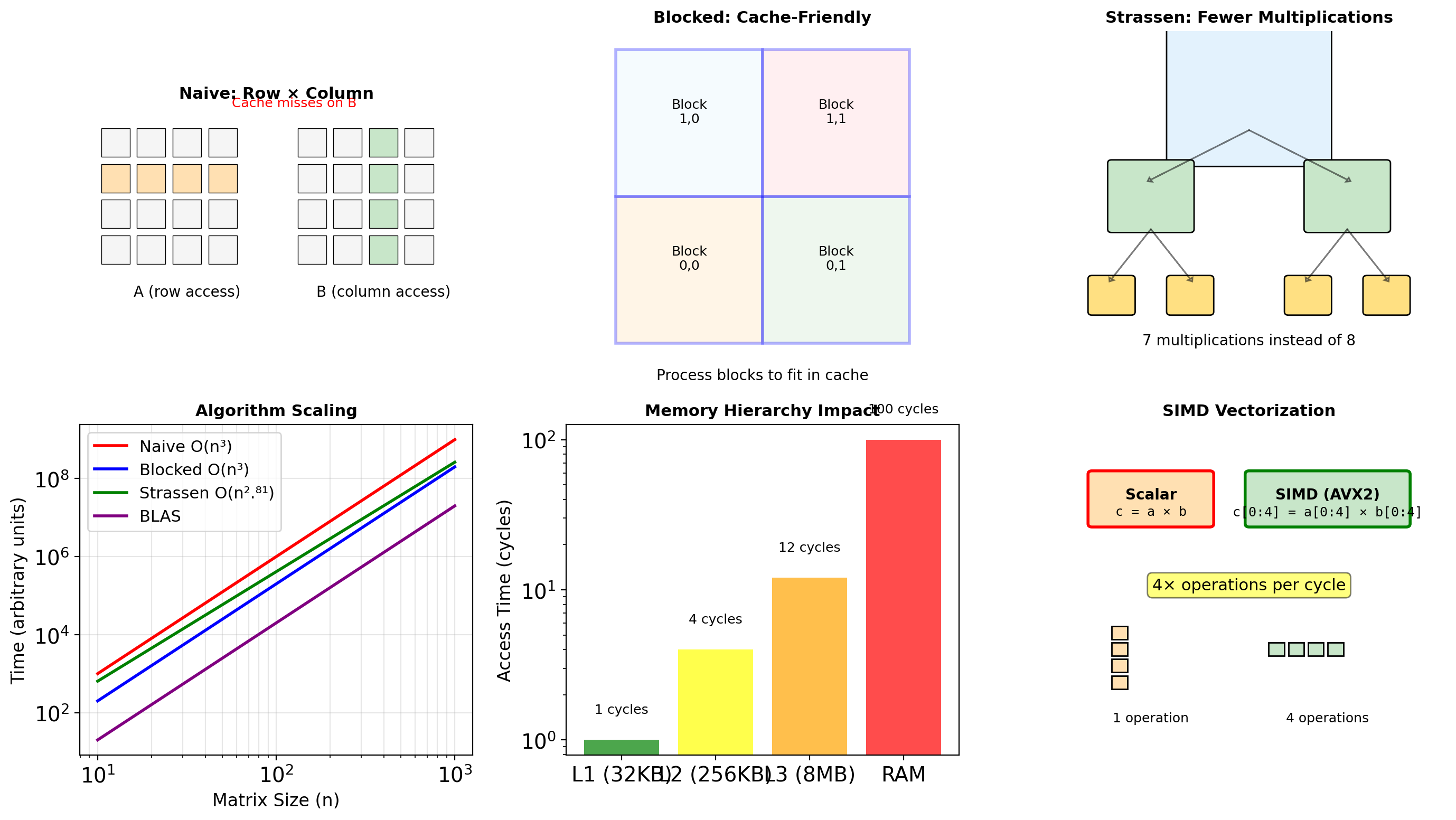

- Why Python is slow; how NumPy fixes it

- Contiguous memory, vectorization

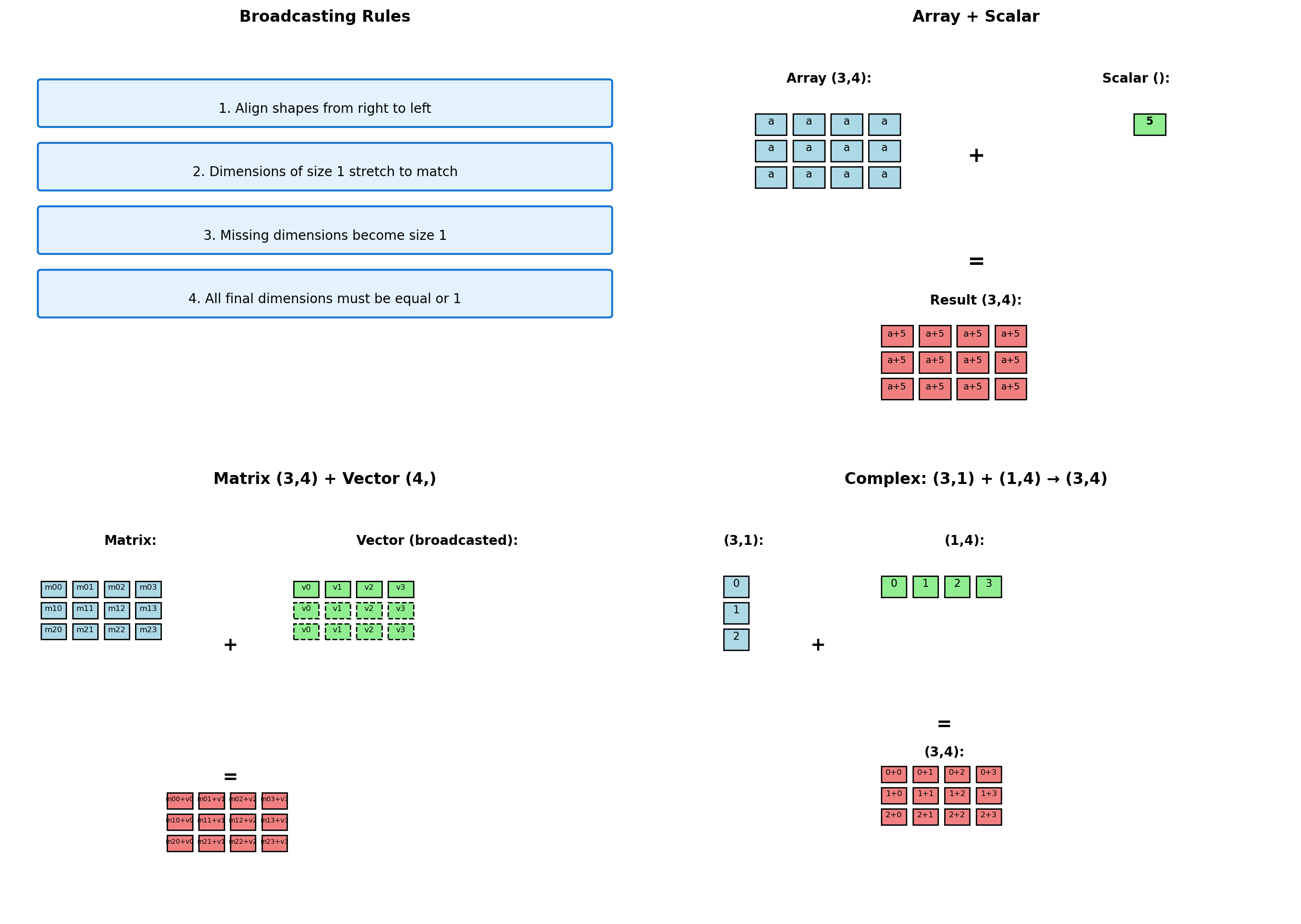

- Broadcasting, views vs copies

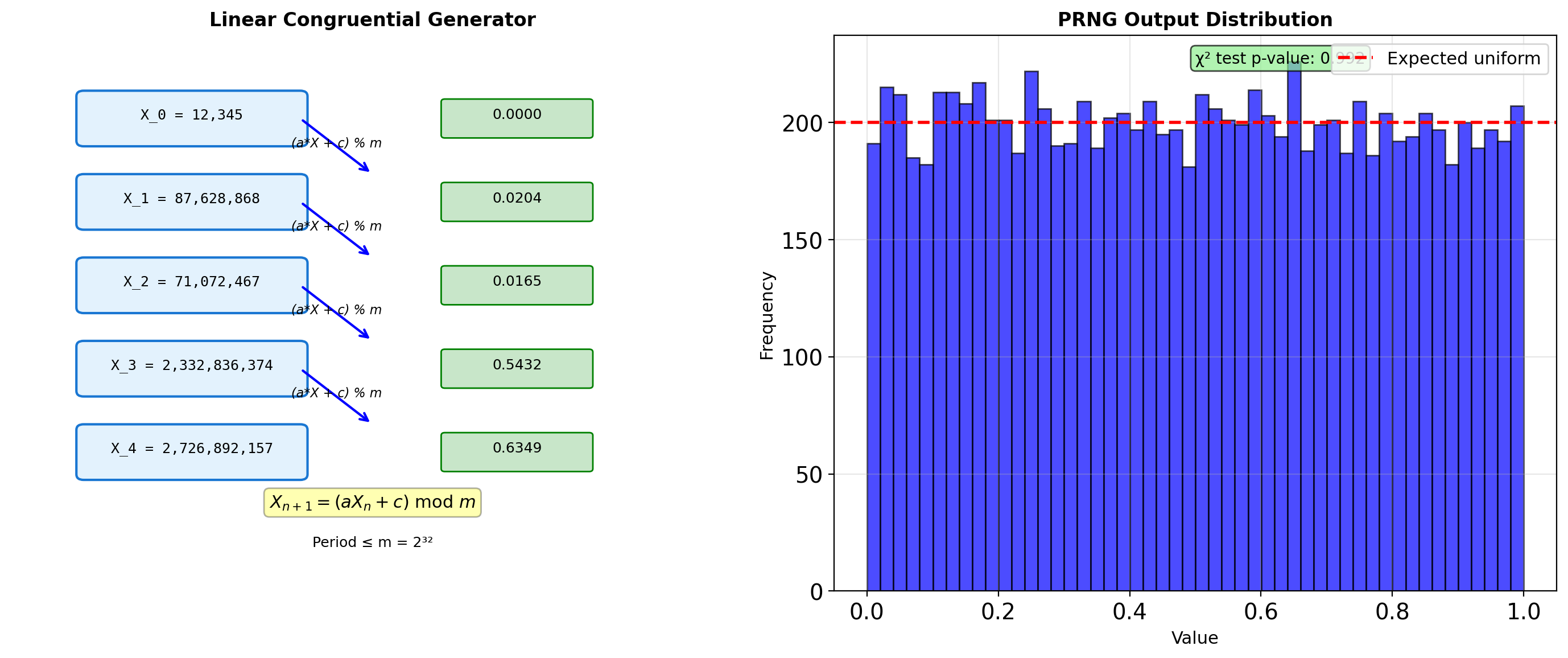

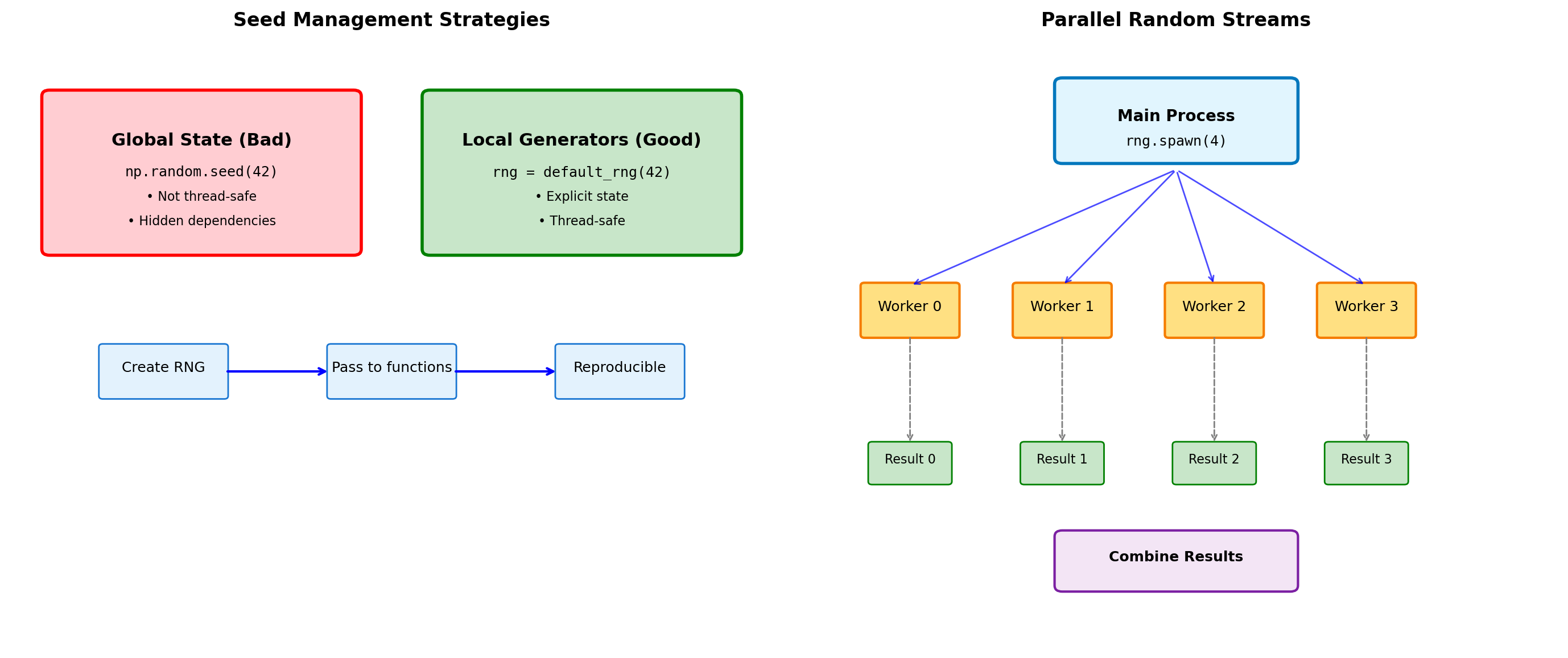

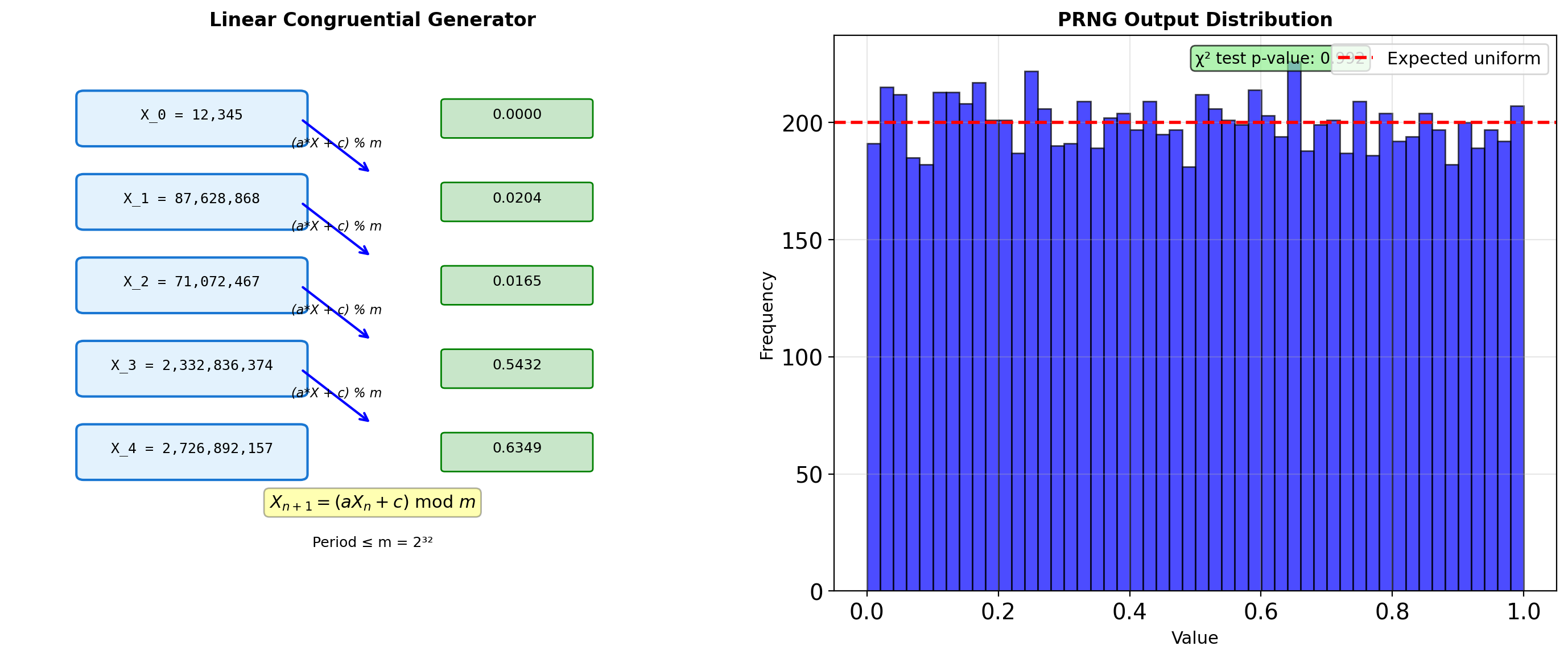

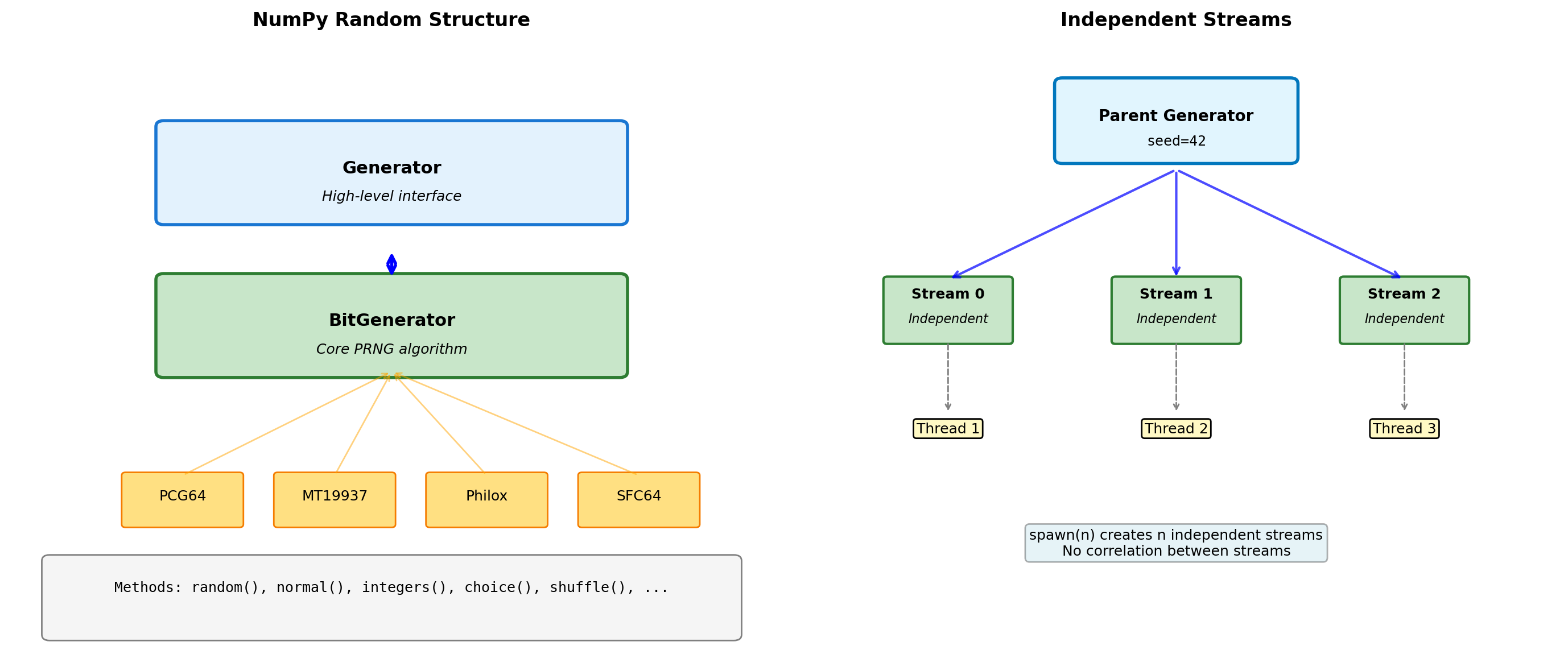

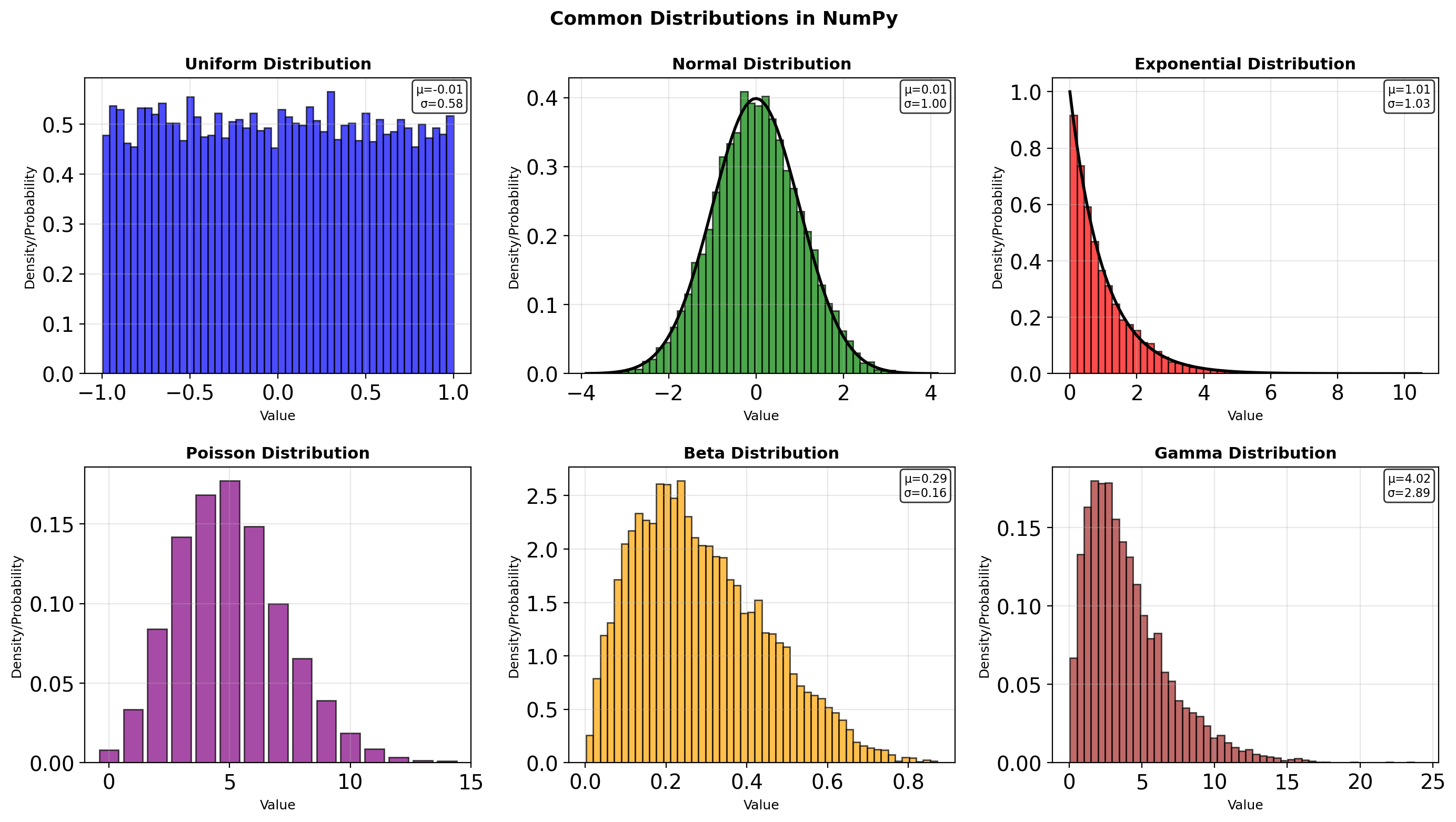

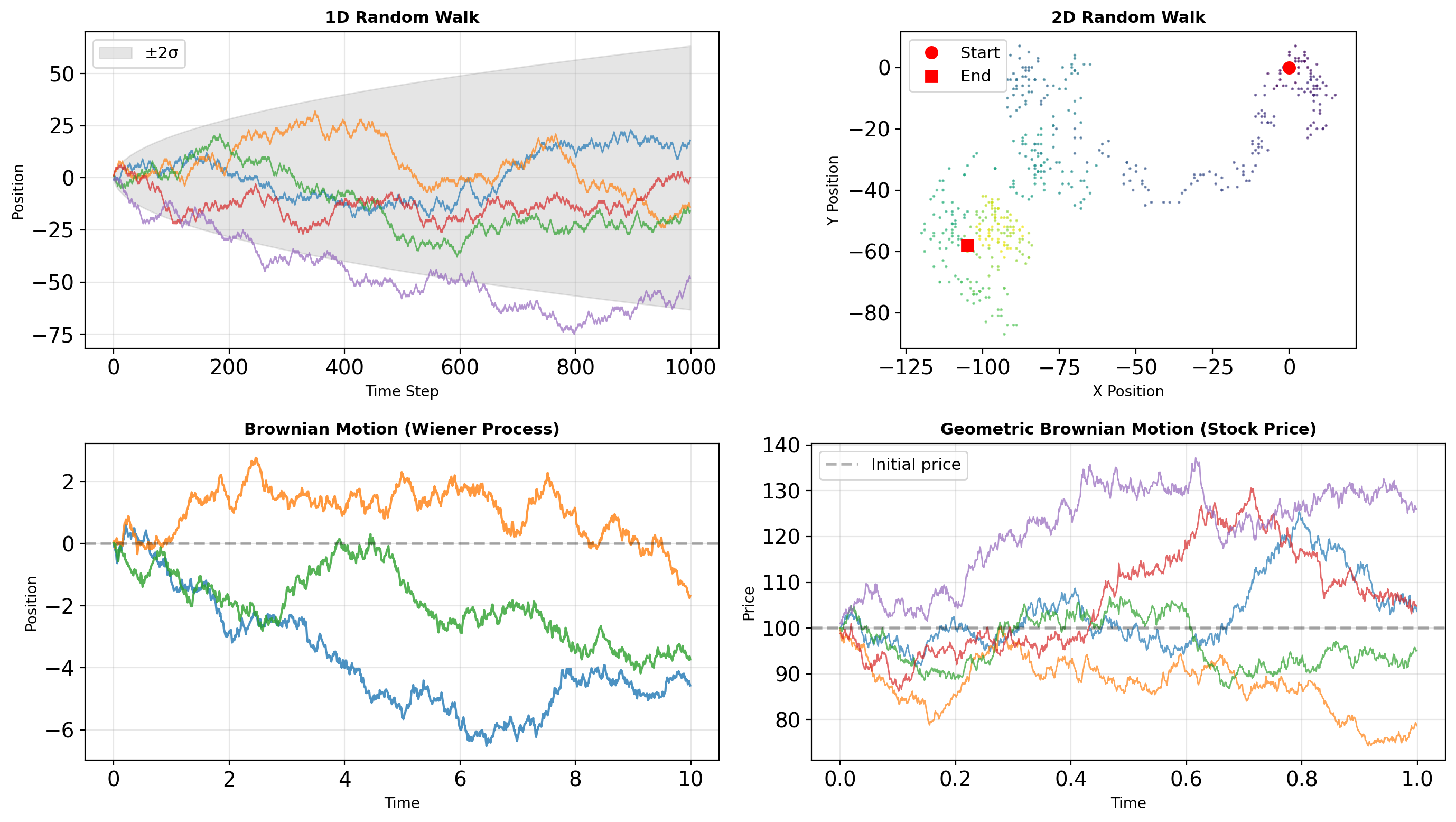

- Generator architecture and reproducibility

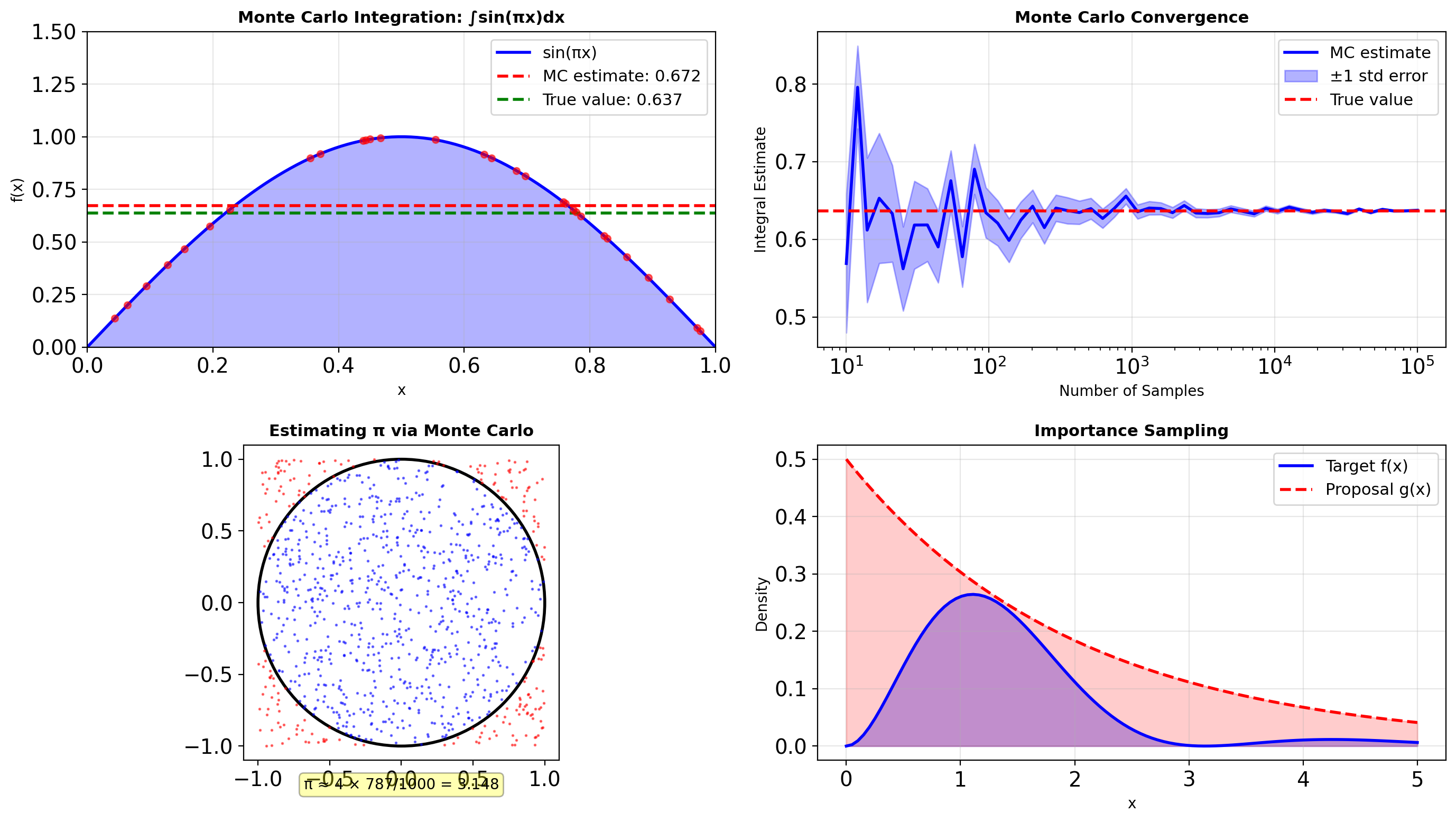

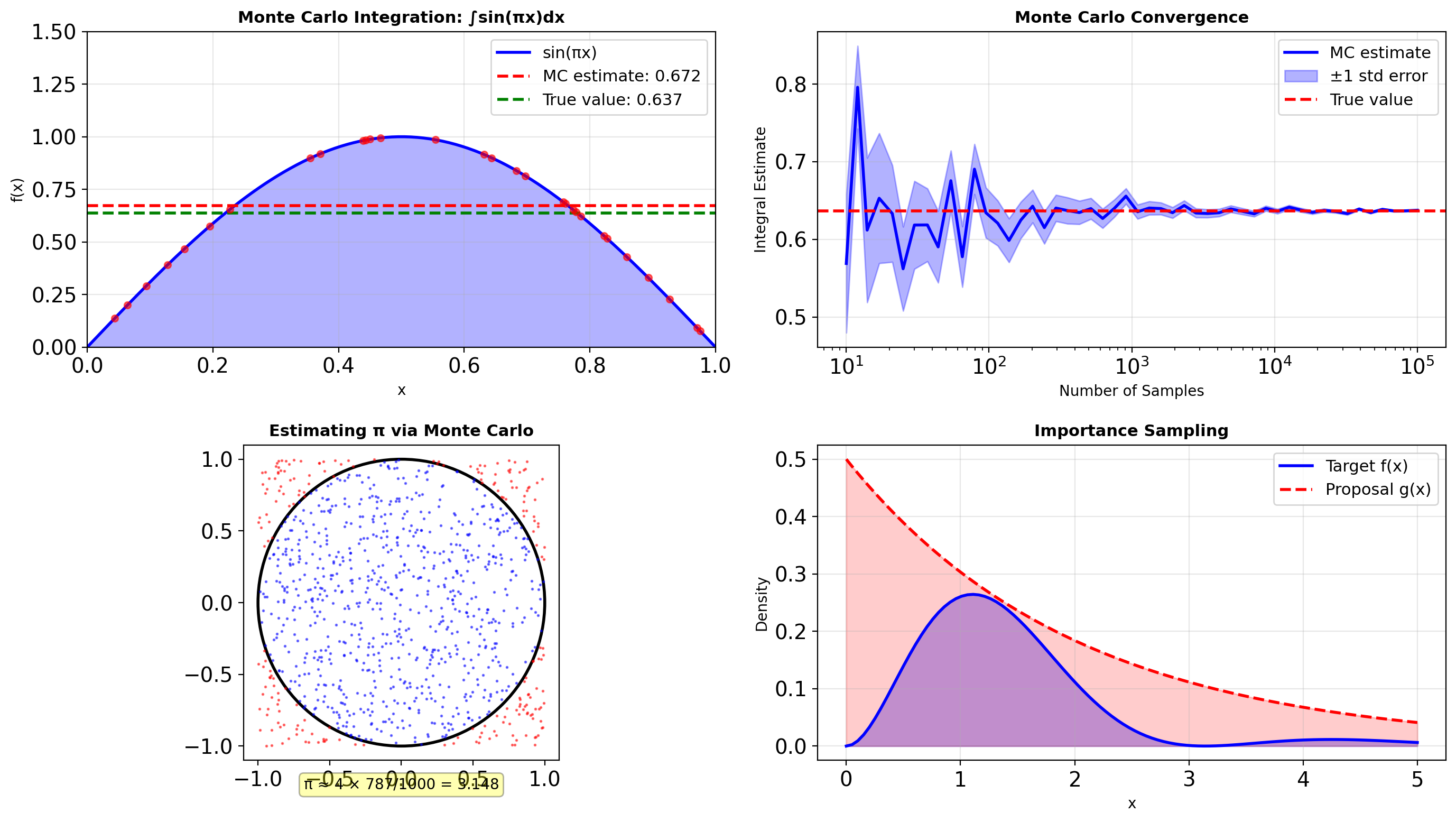

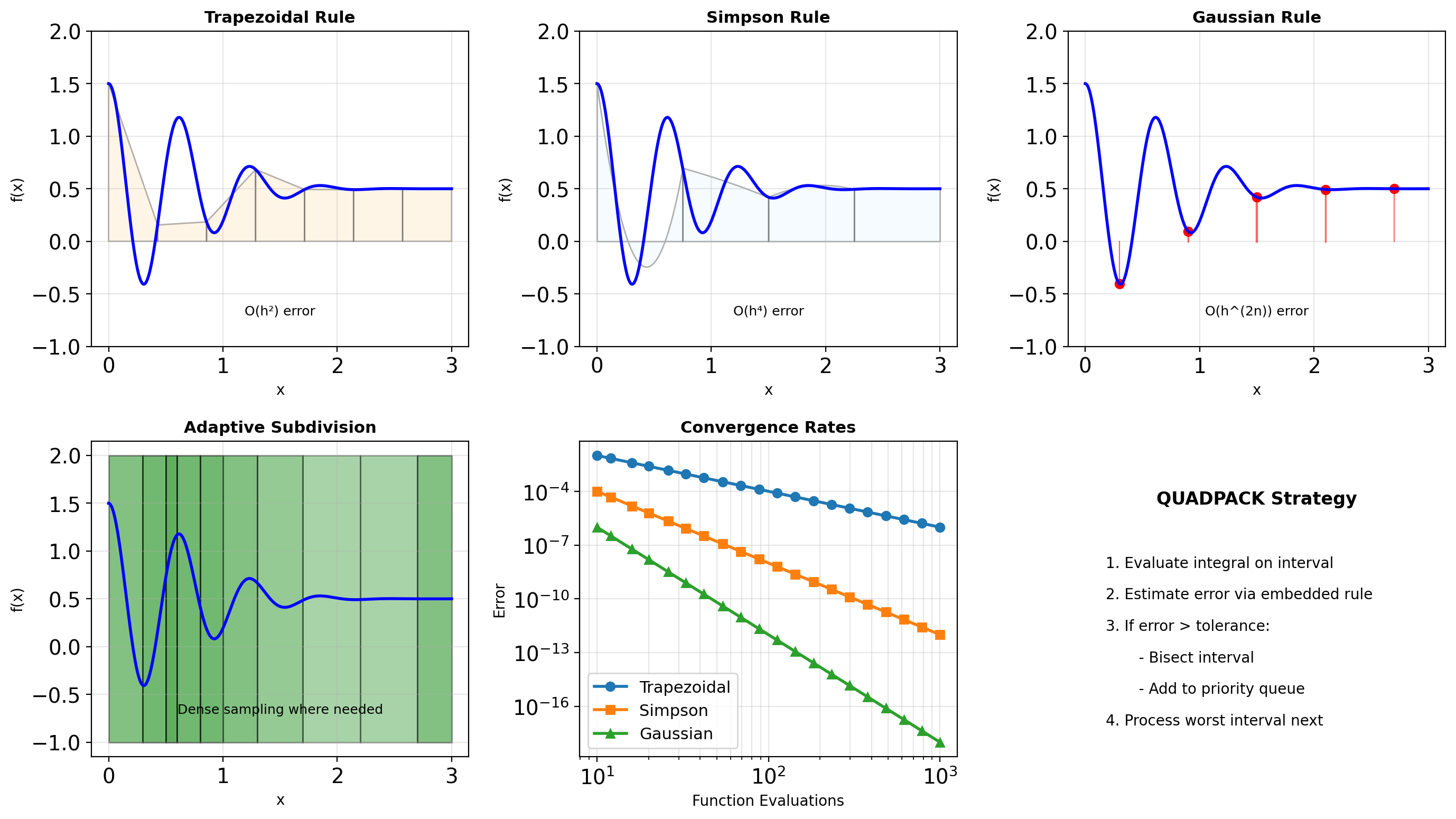

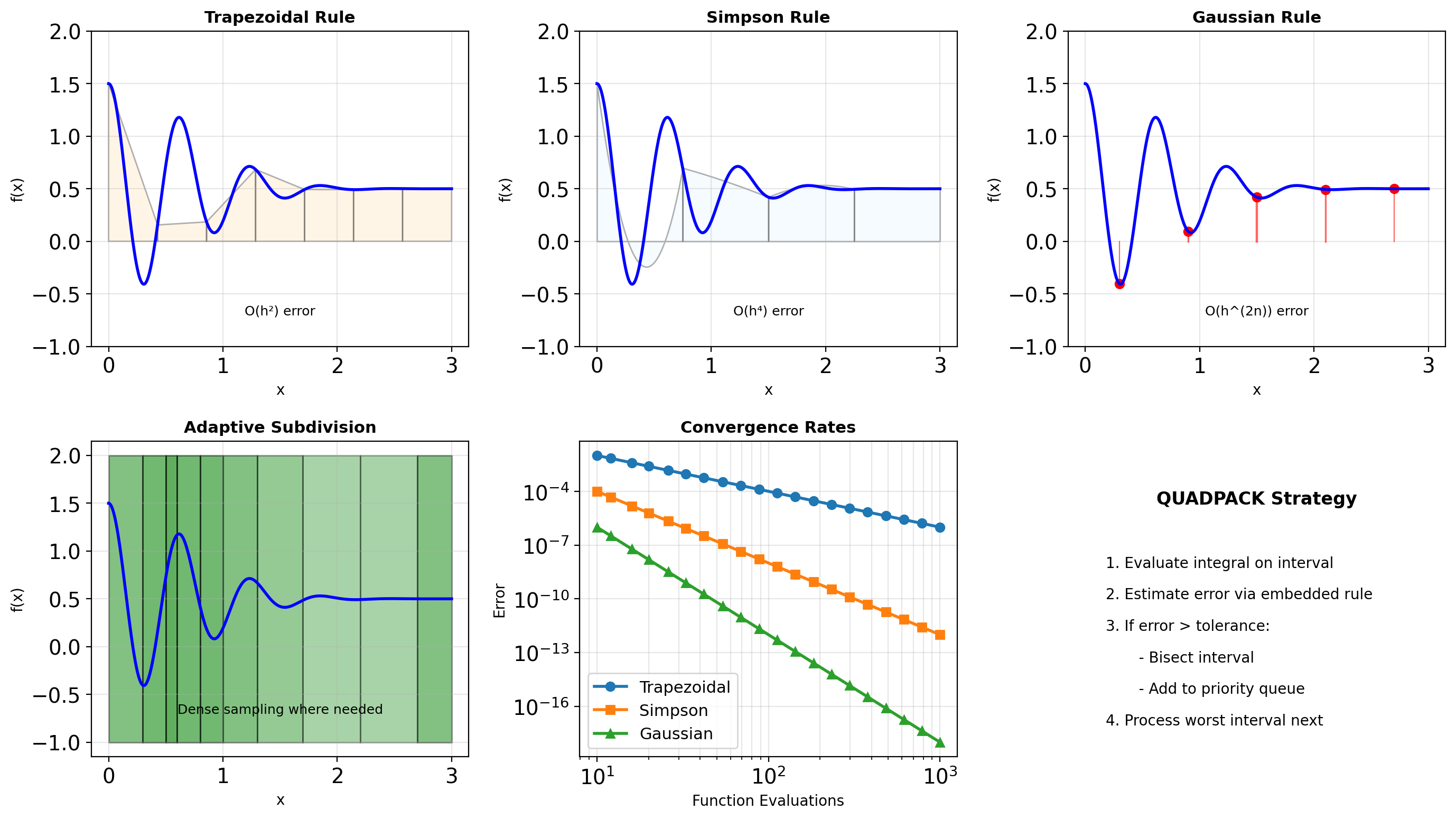

- Monte Carlo integration

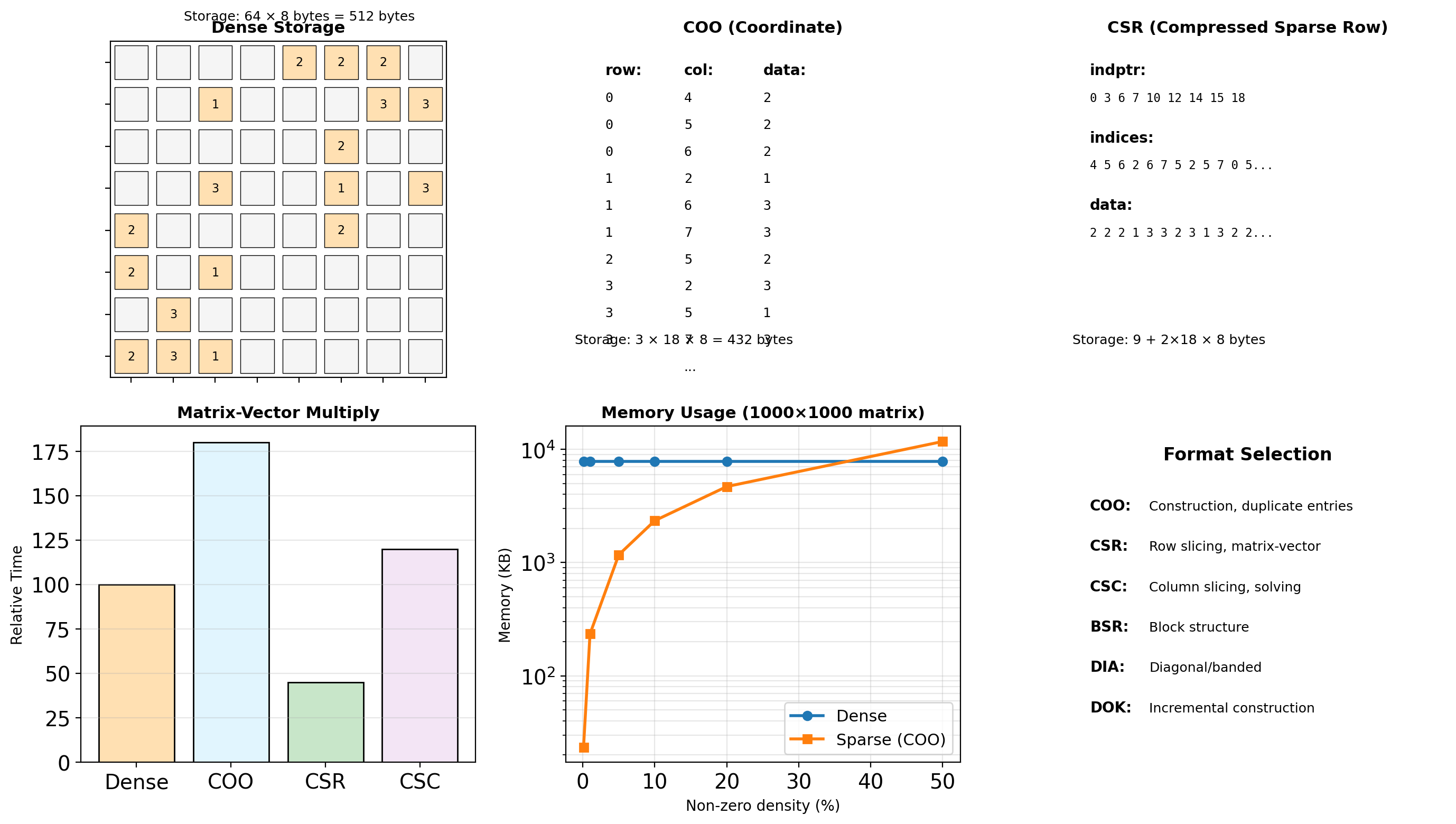

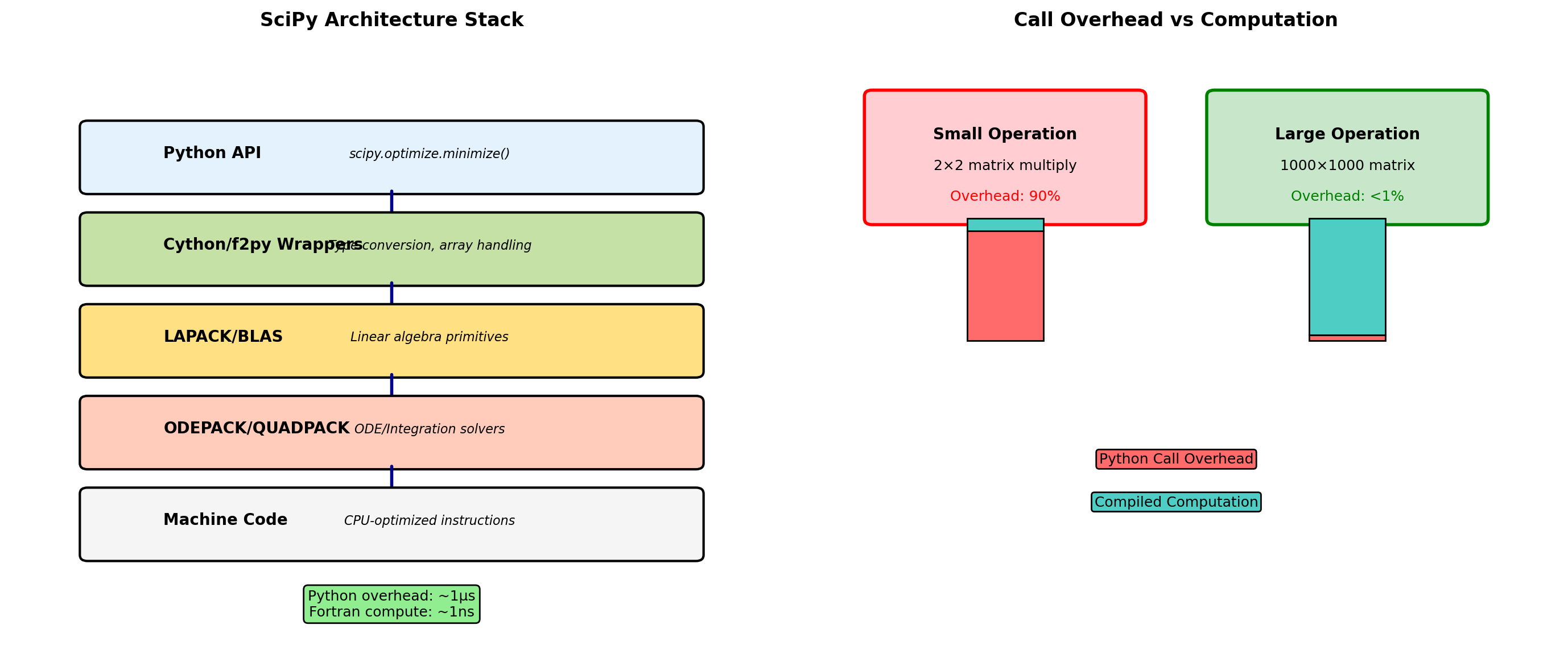

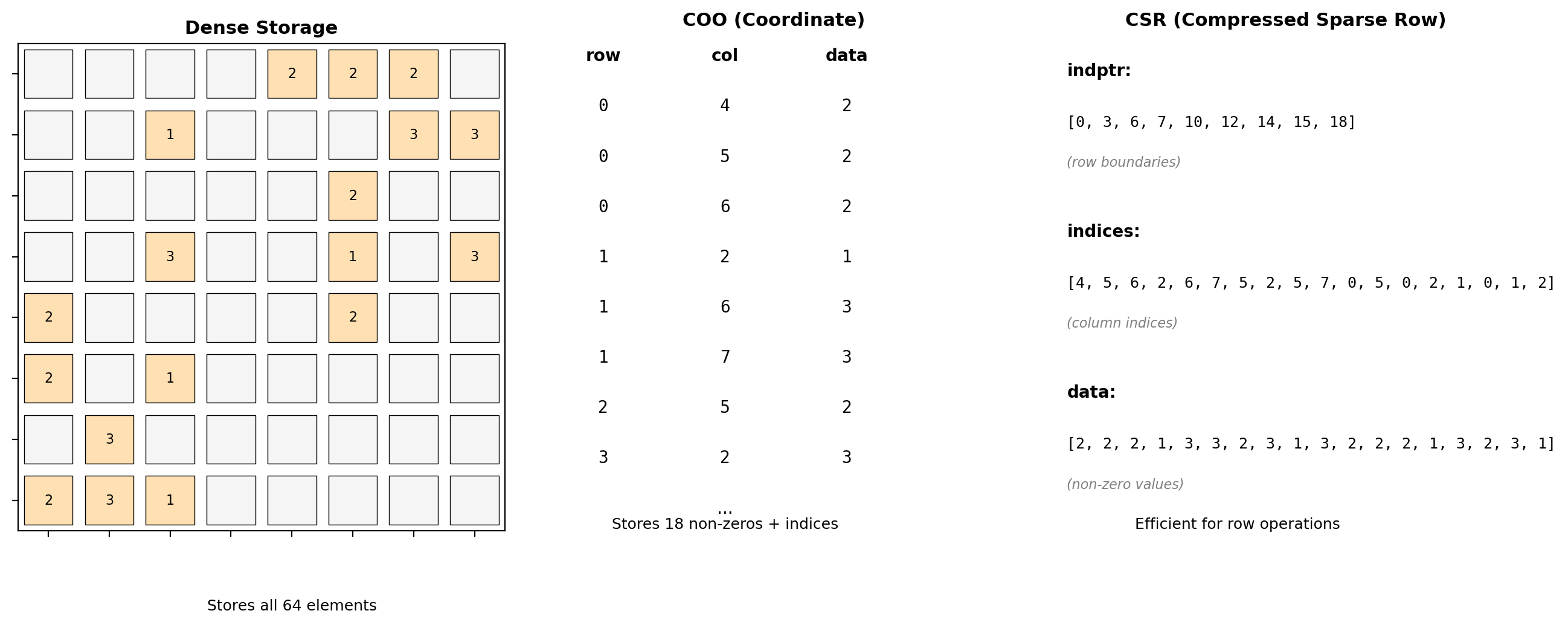

- BLAS/LAPACK wrappers, sparse matrices

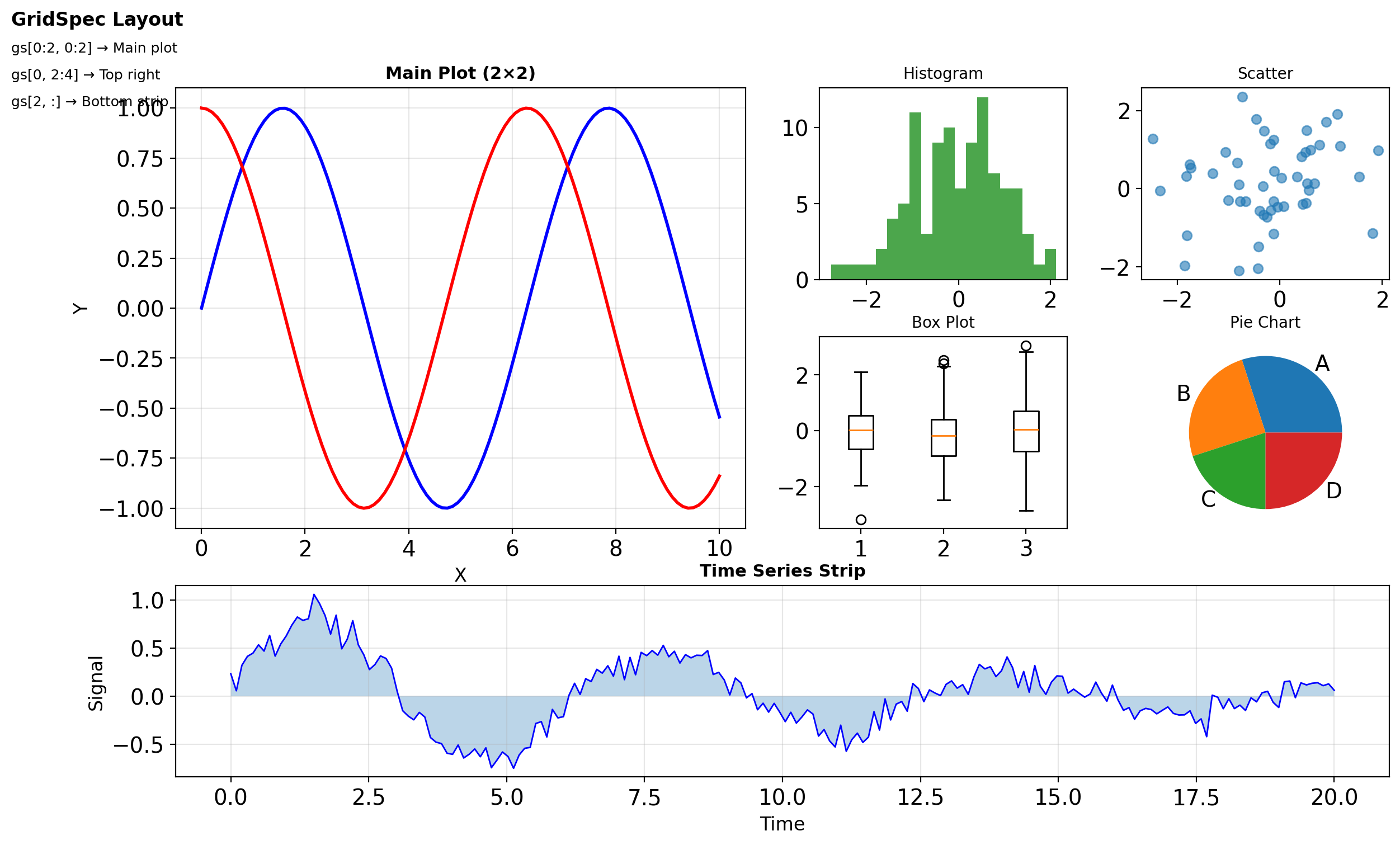

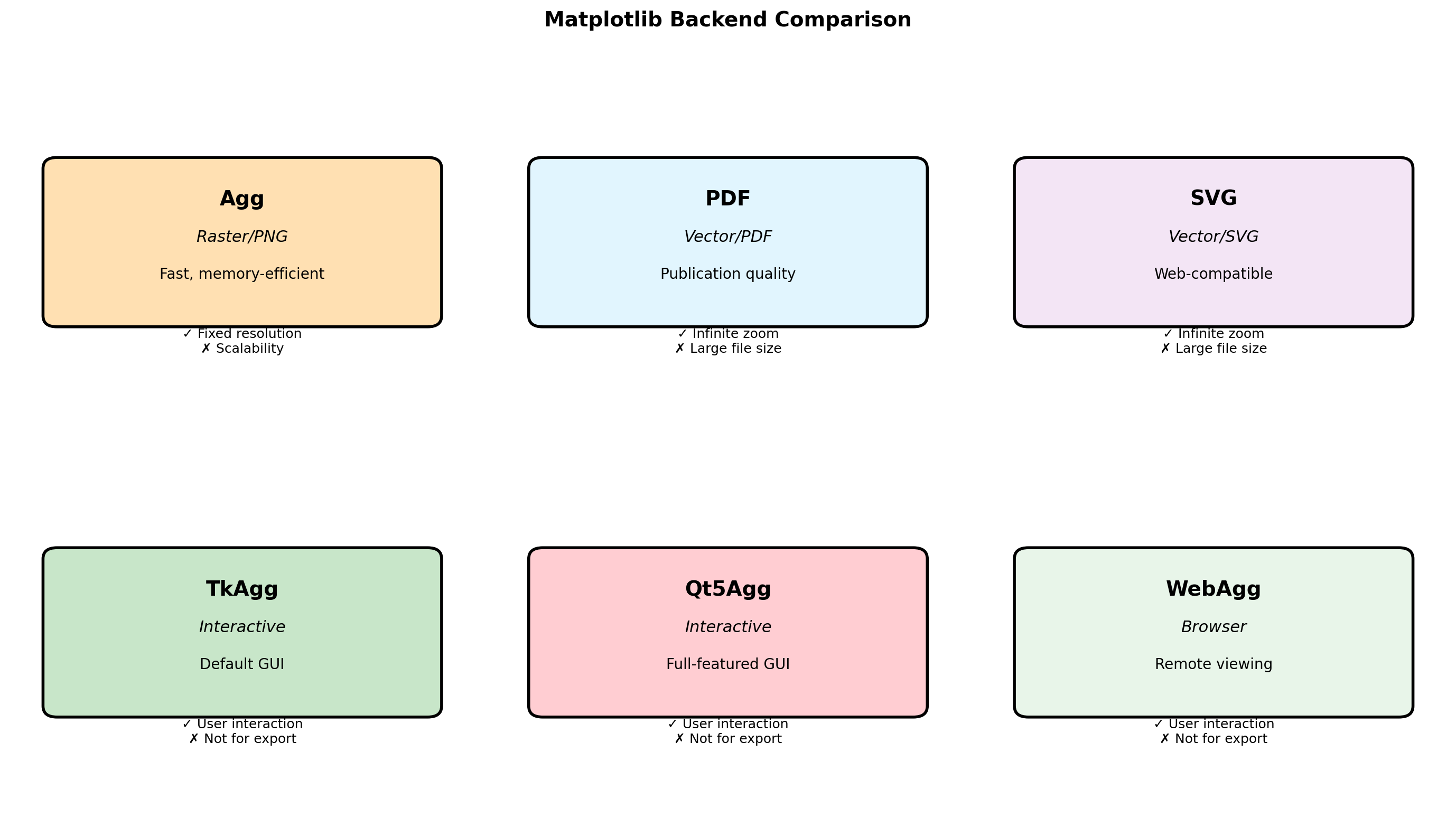

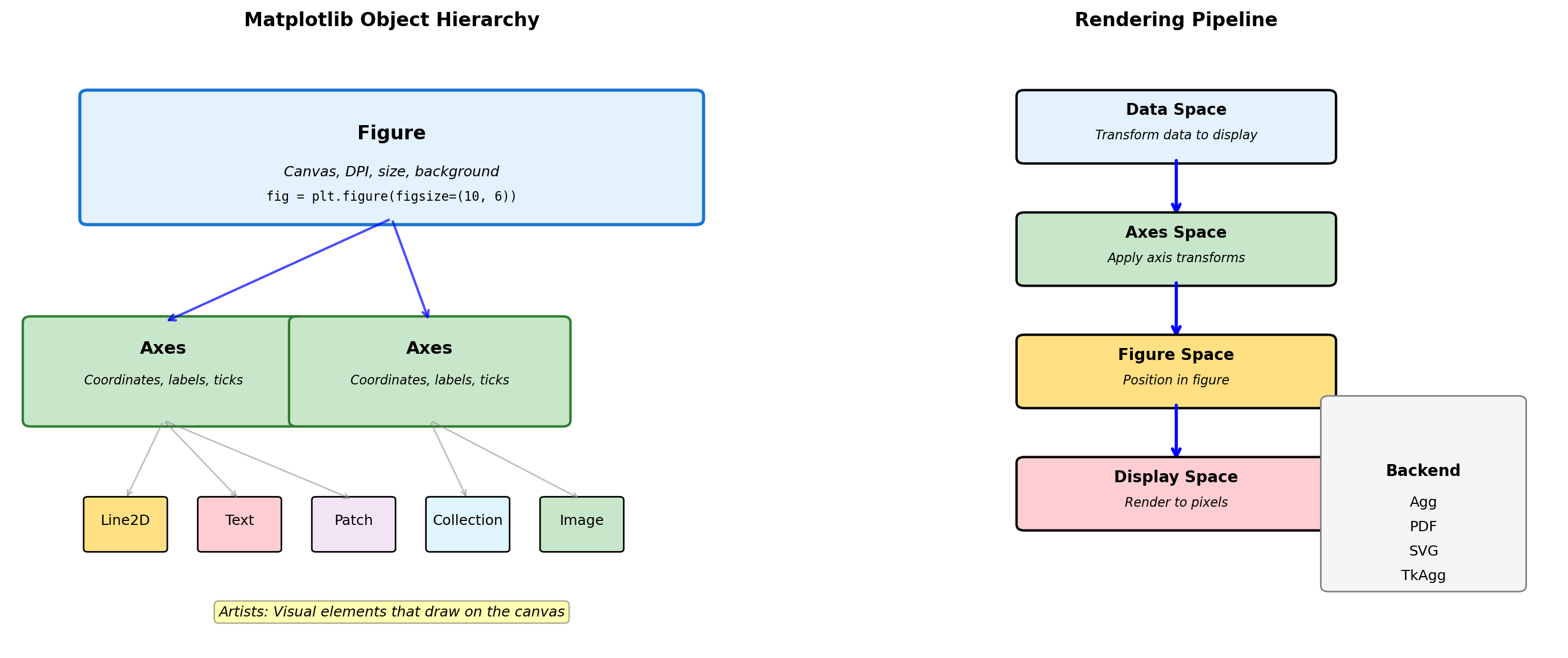

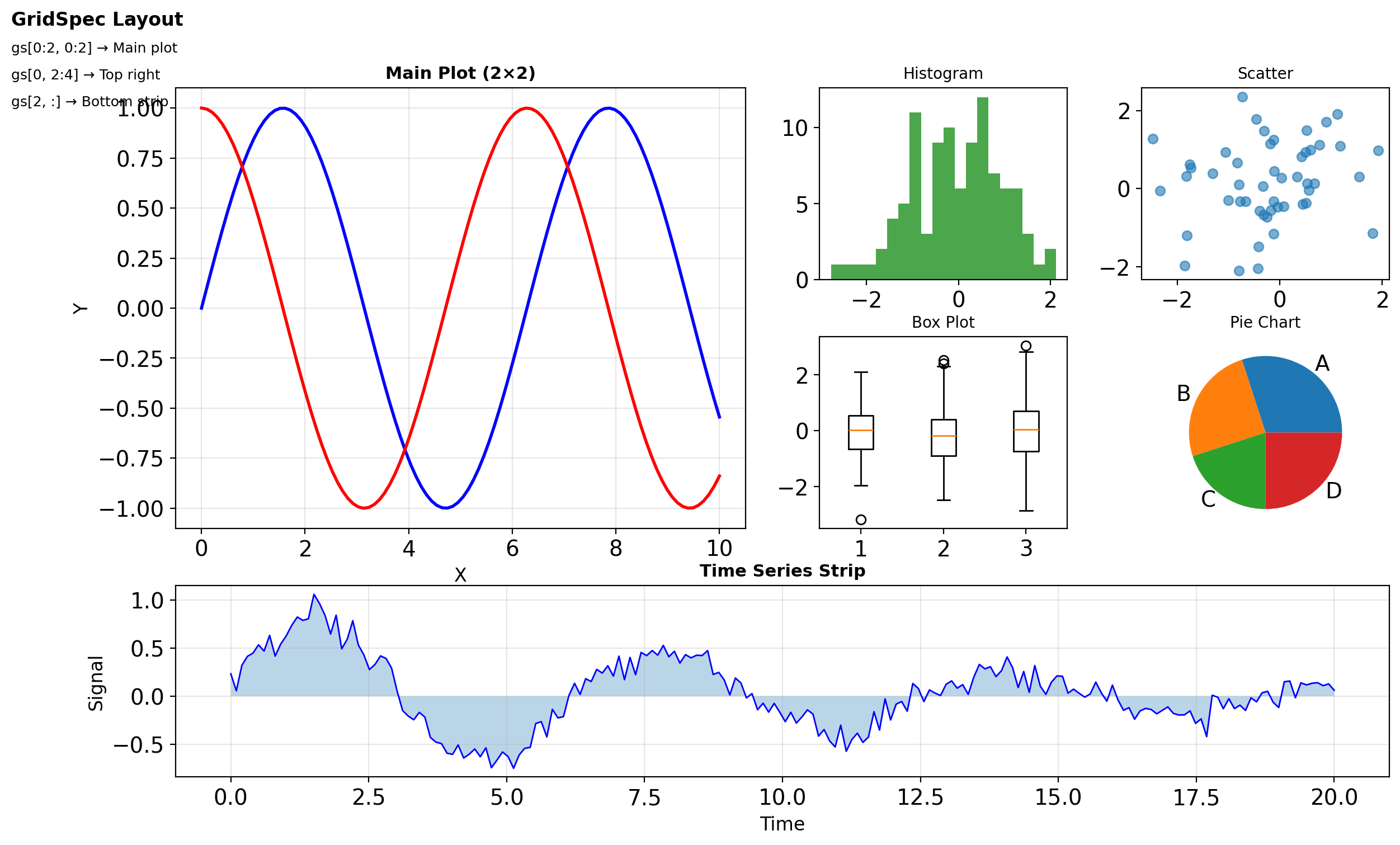

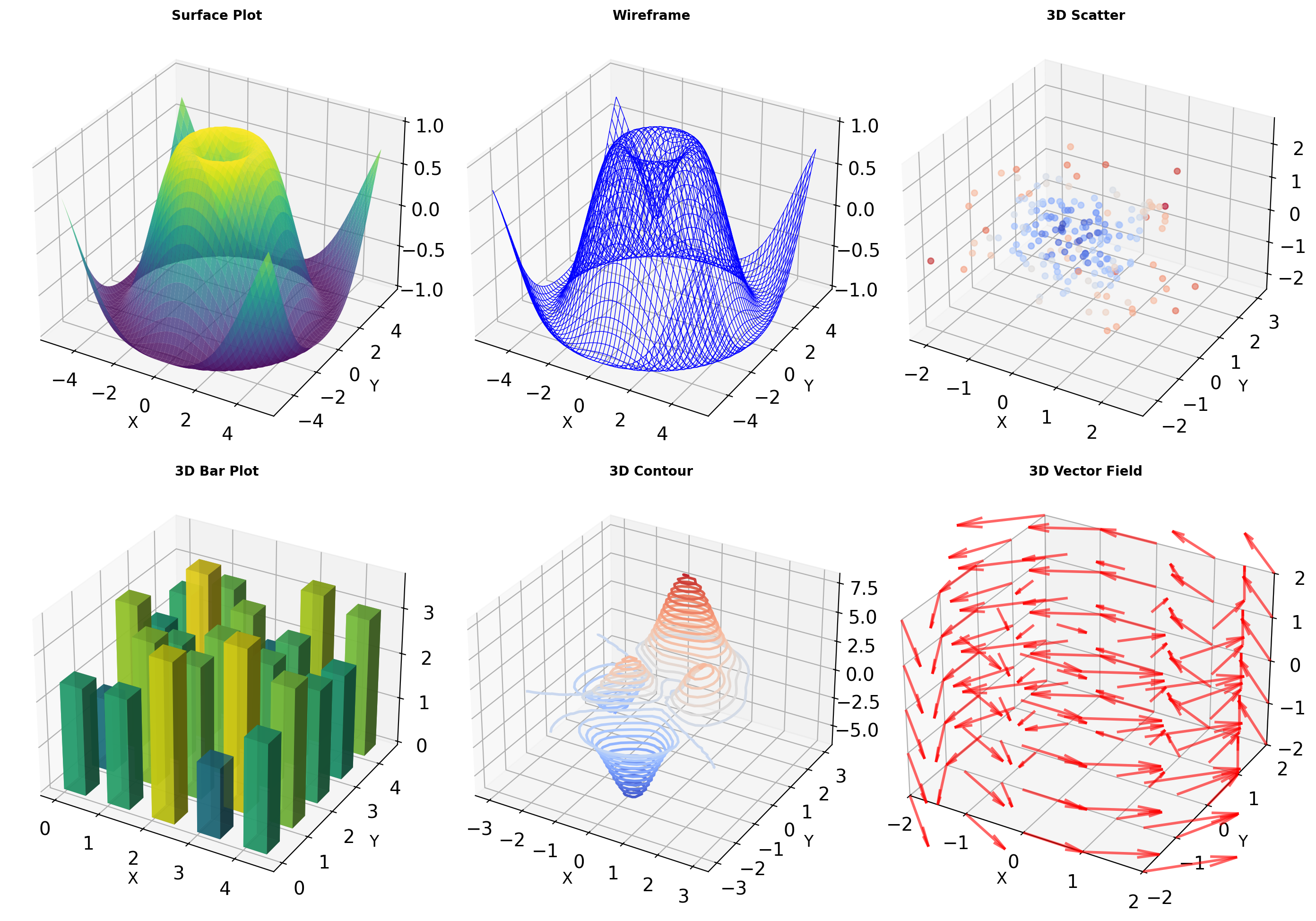

- Matplotlib object hierarchy

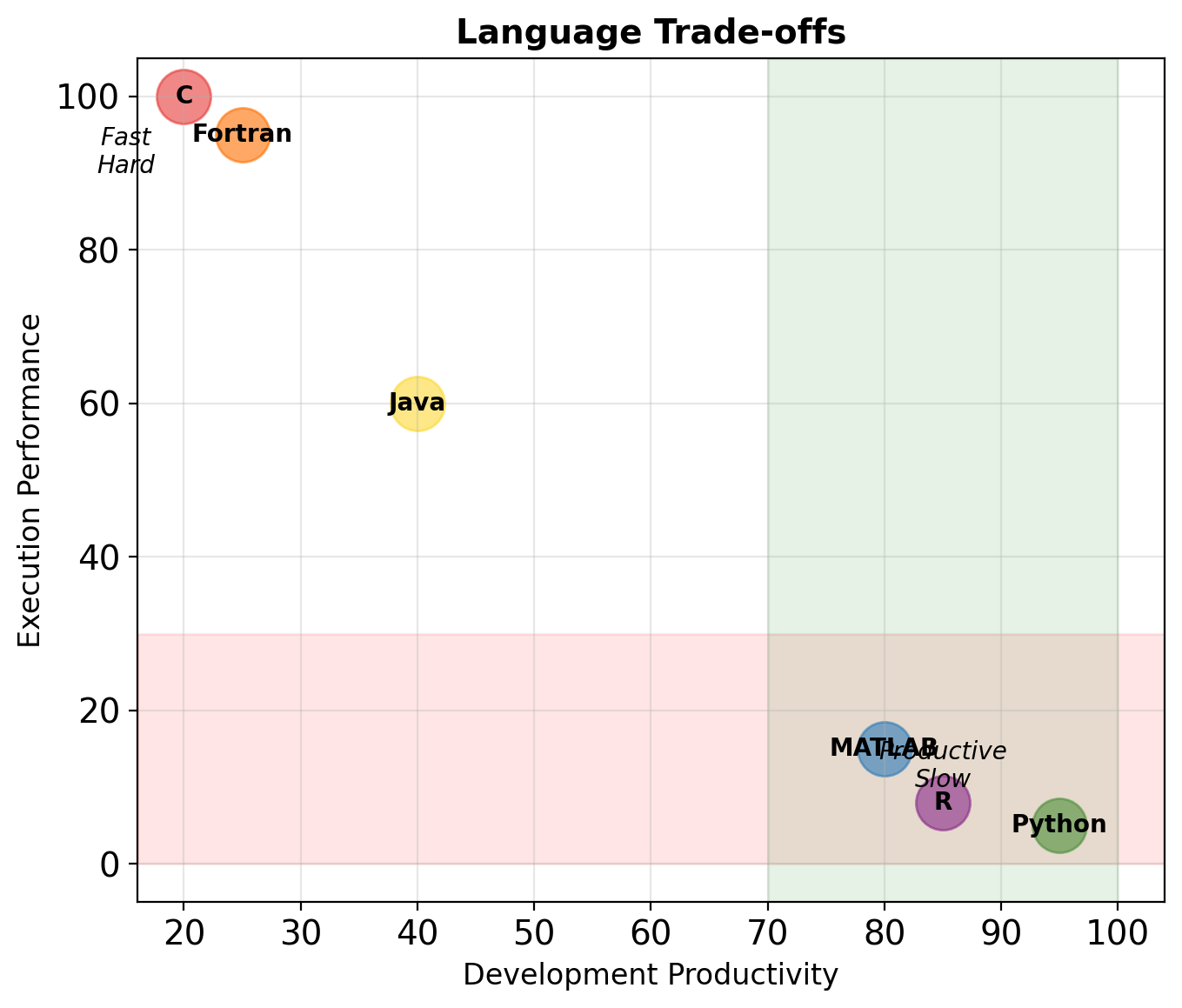

Why Python?

Why Python for Scientific Computing?

A Paradox

Python is 10-100× slower than C/C++ for raw computation, yet dominates scientific computing. Why?

Design Philosophy

- Readability over performance: Code is read more than written

- Dynamic over static: Flexibility for exploration

- Extensive standard library: Reduces external dependencies

- Glue language: Binds fast libraries (NumPy, SciPy use C/Fortran)

The Two-Language Problem

Traditional approach: prototype in MATLAB/Python, rewrite in C++ for production

Python’s approach: Python for control flow, C for computation

Python’s Object Model

Everything in Python is an object:

Every Object Contains:

- Reference count: How many variables point to it

- Type pointer: What kind of object it is

- Value/Data: The actual content

- Additional metadata: Size, flags, etc.

Consequences:

- Integer

5takes 28 bytes (vs 4 in C) - Every operation involves indirection

- Type checking happens at runtime

- Memory scattered across heap

This overhead is why NumPy exists — it stores raw C arrays with a thin Python wrapper.

import sys

# Simple integer

x = 42

print(f"Integer 42:")

print(f" Size: {sys.getsizeof(x)} bytes")

print(f" ID: {id(x):#x}")

print(f" Type: {type(x)}")

# List of integers

lst = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

print(f"\nList [1,2,3,4,5]:")

print(f" List object: {sys.getsizeof(lst)} bytes")

print(f" Plus 5 integers: {5 * sys.getsizeof(1)} bytes")

print(f" Total: ~{sys.getsizeof(lst) + 5*28} bytes")

# C equivalent would be 20 bytes (5 × 4)Integer 42:

Size: 28 bytes

ID: 0x1046734d0

Type: <class 'int'>

List [1,2,3,4,5]:

List object: 104 bytes

Plus 5 integers: 140 bytes

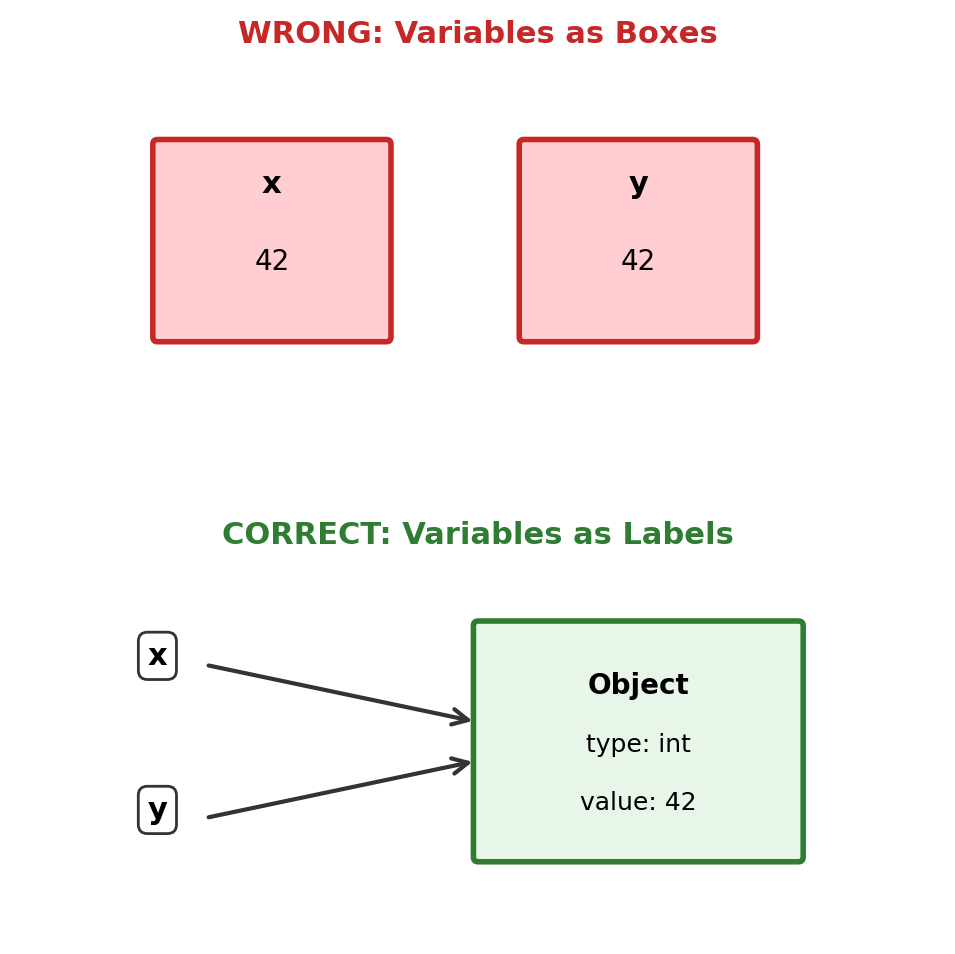

Total: ~244 bytesVariables Are Not Boxes

Variables are names bound to objects, not storage locations.

x = [1, 2, 3] # x refers to a list object

y = x # y refers to THE SAME object

y.append(4) # Modifying through y

print(f"x = {x}") # x sees the change!

# To create a copy:

z = x.copy() # or x[:] or list(x)

z.append(5)

print(f"x = {x}, z = {z}") # x unchangedx = [1, 2, 3, 4]

x = [1, 2, 3, 4], z = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]Assignment creates a reference, not a copy.

Dynamic Typing: Cost and Benefit

Python determines types at runtime, not compile time.

Static Typing (C/Java)

Compiler knows:

- Exact memory layout

- Which CPU instruction to use

- No runtime checks needed

Dynamic Typing (Python)

Runtime must:

- Look up type of

a - Look up type of

b

- Find correct

__add__method - Handle type mismatches

- Create new object for result

Performance Impact

import timeit

import operator

# Python function call overhead

def python_add(a, b):

return a + b

# Direct operator

op_add = operator.add

a, b = 5, 10

n = 1000000

t1 = timeit.timeit(lambda: a + b, number=n)

t2 = timeit.timeit(lambda: op_add(a, b), number=n)

t3 = timeit.timeit(lambda: python_add(a, b), number=n)

print(f"Direct +: {t1:.3f}s")

print(f"operator.add: {t2:.3f}s ({t2/t1:.1f}x slower)")

print(f"Function: {t3:.3f}s ({t3/t1:.1f}x slower)")Direct +: 0.019s

operator.add: 0.024s (1.3x slower)

Function: 0.033s (1.7x slower)Control Flow: Iterator Protocol

Every for loop in Python uses the iterator protocol, not index-based access.

What Really Happens

Translates to:

iterator = iter(sequence)

while True:

try:

item = next(iterator)

process(item)

except StopIteration:

breakThis Enables:

- Lazy evaluation (generators)

- Infinite sequences

- Custom iteration behavior

- Memory efficiency

# Create a custom iterator

class Fibonacci:

def __init__(self, max_n):

self.max_n = max_n

self.n = 0

self.current = 0

self.next_val = 1

def __iter__(self):

return self

def __next__(self):

if self.n >= self.max_n:

raise StopIteration

result = self.current

self.current, self.next_val = \

self.next_val, self.current + self.next_val

self.n += 1

return result

# Use like any sequence

for f in Fibonacci(10):

print(f, end=' ')

print()

# This is why range() is memory efficient

print(f"\nrange(1000000): {sys.getsizeof(range(1000000))} bytes")0 1 1 2 3 5 8 13 21 34

range(1000000): 48 bytesFunctions: More Than Subroutines

Python functions are objects with attributes, not just code blocks.

Functions Are Objects

- Have attributes (

__name__,__doc__) - Can be assigned to variables

- Can be passed as arguments

- Can be returned from functions

- Carry their environment (closures)

This Enables:

- Functional programming patterns

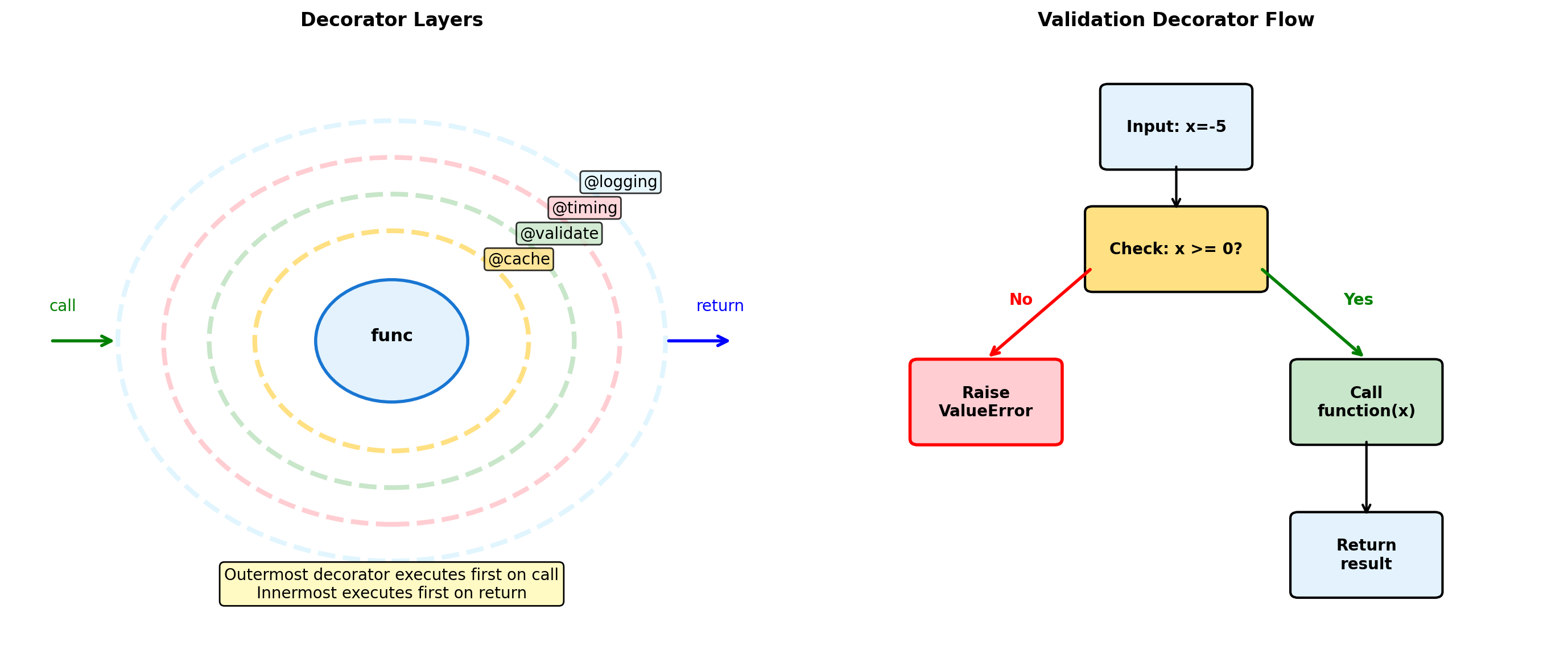

- Decorators for cross-cutting concerns

- Callbacks and event handlers

- Factory functions

Key insight: Functions remember their creation environment.

def make_multiplier(n):

"""Factory function creating closures."""

def multiplier(x):

return x * n # n is captured

# Function is an object we can modify

multiplier.factor = n

multiplier.__name__ = f'times_{n}'

return multiplier

times_2 = make_multiplier(2)

times_10 = make_multiplier(10)

print(f"{times_2.__name__}: {times_2(5)}")

print(f"{times_10.__name__}: {times_10(5)}")

print(f"Factors: {times_2.factor}, {times_10.factor}")

# Inspect closure

import inspect

closure_vars = inspect.getclosurevars(times_2)

print(f"Captured: {closure_vars.nonlocals}")times_2: 10

times_10: 50

Factors: 2, 10

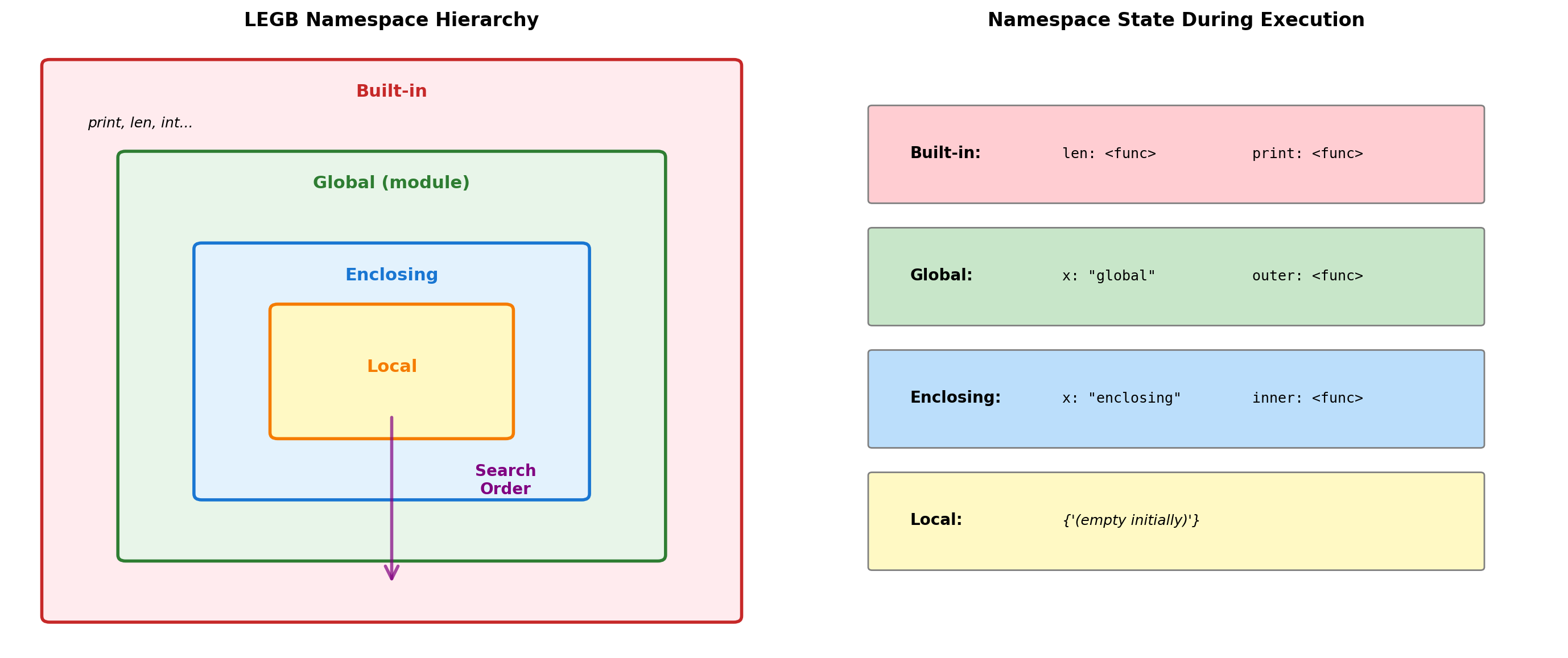

Captured: {'n': 2}Namespace Resolution: The LEGB Rule

Python resolves names through a hierarchy of namespace dictionaries.

x = "global" # Global namespace

def outer():

x = "enclosing" # Enclosing namespace

def inner():

print(f"Reading x: {x}") # LEGB search finds enclosing

def inner_local():

x = "local" # Creates local binding

print(f"Local x: {x}")

inner()

inner_local()

print(f"Enclosing x: {x}")

outer()

print(f"Global x: {x}")

# Namespace modification

def show_namespace_dict():

local_var = 42

print(f"locals(): {locals()}")

print(f"'local_var' in locals(): {'local_var' in locals()}")

show_namespace_dict()Reading x: enclosing

Local x: local

Enclosing x: enclosing

Global x: global

locals(): {'local_var': 42}

'local_var' in locals(): TrueResolution Rules:

- Local: Current function’s namespace

- Enclosing: Outer function(s) namespace

- Global: Module-level namespace

- Built-in: Pre-defined names

Binding Behavior:

- Assignment creates local binding by default

globalkeyword binds to global namespacenonlocalbinds to enclosing namespace- Reading doesn’t create binding

# UnboundLocalError example

count = 0

def increment():

# Python sees assignment, creates local slot

# But referenced before assignment

try:

count += 1 # UnboundLocalError

except UnboundLocalError as e:

print(f"Error: {e}")

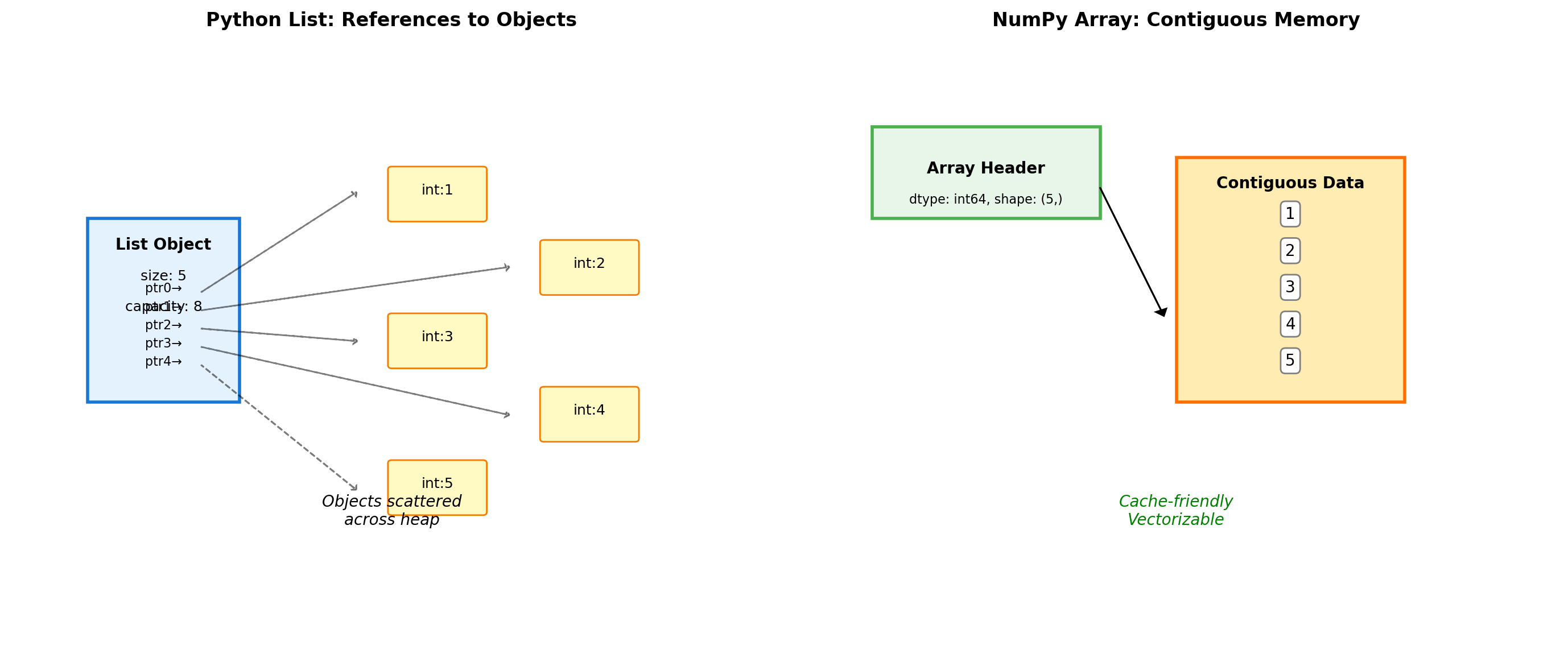

increment()Error: cannot access local variable 'count' where it is not associated with a valueLists vs Arrays: Memory Layout Matters

Python lists and NumPy arrays have different memory layouts.

import numpy as np

# Memory comparison

py_list = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

np_array = np.array([1, 2, 3, 4, 5])

print(f"Python list overhead: {sys.getsizeof(py_list)} bytes")

print(f"NumPy array overhead: {sys.getsizeof(np_array)} bytes")

print(f"NumPy data buffer: {np_array.nbytes} bytes")

# Performance impact

import timeit

lst = list(range(1000))

arr = np.arange(1000)

t_list = timeit.timeit(lambda: sum(lst), number=10000)

t_numpy = timeit.timeit(lambda: arr.sum(), number=10000)

print(f"\nSum 1000 elements:")

print(f"Python list: {t_list:.4f}s")

print(f"NumPy array: {t_numpy:.4f}s ({t_list/t_numpy:.1f}x faster)")Python list overhead: 104 bytes

NumPy array overhead: 152 bytes

NumPy data buffer: 40 bytes

Sum 1000 elements:

Python list: 0.0299s

NumPy array: 0.0073s (4.1x faster)Mutable vs Immutable: Design Consequences

Python’s distinction between mutable and immutable types affects program design.

Immutable Types

- int, float, str, tuple

- Cannot be changed after creation

- Safe to use as dict keys

- Thread-safe by default

- Can be cached/interned

Mutable Types

- list, dict, set, most objects

- Can be modified in place

- Cannot be dict keys

- Require synchronization

- Lead to aliasing bugs

# Immutable: operations create new objects

s = "hello"

print(f"Original id: {id(s):#x}")

s = s + " world" # Creates new object

print(f"After +=: {id(s):#x}")

# Mutable: operations modify in place

lst = [1, 2, 3]

original_id = id(lst)

lst.append(4) # Modifies in place

print(f"\nList id before: {original_id:#x}")

print(f"List id after: {id(lst):#x}")

print(f"Same object: {id(lst) == original_id}")

# The danger of mutable defaults

def add_to_list(item, target=[]): # Mutable default argument

target.append(item)

return target

list1 = add_to_list(1)

list2 = add_to_list(2) # Shares same default list

print(f"\nlist1: {list1}")

print(f"list2: {list2}")

print(f"Same object: {list1 is list2}")Original id: 0x110864cb0

After +=: 0x31f32ee30

List id before: 0x31f3d72c0

List id after: 0x31f3d72c0

Same object: True

list1: [1, 2]

list2: [1, 2]

Same object: TrueException Handling: Not Just Error Catching

Exceptions are Python’s control flow mechanism for exceptional cases.

Exceptions Are:

- Part of normal control flow

- Used by iterators (StopIteration)

- Hierarchical (inheritance-based catching)

- Expensive when raised, cheap when not

EAFP vs LBYL

- EAFP: Easier to Ask Forgiveness than Permission

- LBYL: Look Before You Leap

Python prefers EAFP:

import timeit

# EAFP vs LBYL performance

d = {str(i): i for i in range(100)}

def eafp_found():

try:

return d['50']

except KeyError:

return None

def lbyl_found():

if '50' in d:

return d['50']

return None

def eafp_not_found():

try:

return d['200']

except KeyError:

return None

def lbyl_not_found():

if '200' in d:

return d['200']

return None

n = 100000

print("Key exists:")

print(f" EAFP: {timeit.timeit(eafp_found, number=n):.3f}s")

print(f" LBYL: {timeit.timeit(lbyl_found, number=n):.3f}s")

print("Key missing:")

print(f" EAFP: {timeit.timeit(eafp_not_found, number=n):.3f}s")

print(f" LBYL: {timeit.timeit(lbyl_not_found, number=n):.3f}s")Key exists:

EAFP: 0.002s

LBYL: 0.004s

Key missing:

EAFP: 0.009s

LBYL: 0.002sPerformance: Optimization Strategies

Understanding Python’s overhead helps write efficient code.

Optimization Strategies:

- Vectorize with NumPy - Move loops to C

- Use built-in functions - Implemented in C

- Avoid function calls in loops - High overhead

- Cache method lookups -

append = lst.append - Use appropriate data structures - set for membership, deque for queues

# Example: Method lookup caching

data = []

n = 100000

# Slow: lookup append each time

start = timeit.default_timer()

for i in range(n):

data.append(i)

slow_time = timeit.default_timer() - start

# Fast: cache the method

data = []

append = data.append # Cache method lookup

start = timeit.default_timer()

for i in range(n):

append(i)

fast_time = timeit.default_timer() - start

print(f"Normal: {slow_time:.4f}s")

print(f"Cached: {fast_time:.4f}s ({slow_time/fast_time:.2f}x faster)")Normal: 0.0034s

Cached: 0.0039s (0.89x faster)Python Syntax Primer

What is Python?

Python is an interpreted, dynamically-typed, garbage-collected language.

Interpreted vs Compiled

| Compiled (C/C++) | Interpreted (Python) |

|---|---|

| Source → Machine code | Source → Bytecode → VM |

| Compile once, run fast | No compile step visible |

| Platform-specific binary | Platform-independent .pyc |

| Errors at compile time | Errors at runtime |

Python actually compiles to bytecode (.pyc files), then the Python Virtual Machine (PVM) interprets that bytecode. This is similar to Java’s JVM model.

Running Python Code

Three ways to run Python:

Interactive interpreter (REPL)

Script files

Jupyter notebooks

- Interactive cells mixing code, output, markdown

- Popular for exploration and visualization

The python command

When you type python script.py:

- Python reads

script.py(text file) - Lexer/parser converts to AST

- Compiler generates bytecode

- PVM executes bytecode line by line

Script structure:

Python’s Execution Model

Why this matters:

- No separate compile step — edit and run immediately

- Runtime errors only — syntax errors found when line executes

- Slower than native code — bytecode interpretation has overhead

- Dynamic features — can modify code at runtime (

eval,exec)

Comparison:

| C++ | Java | Python | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compile to | Machine code | JVM bytecode | PVM bytecode |

| Type checking | Compile time | Compile time | Runtime |

| Speed | Fast | Medium | Slow |

| Edit-run cycle | Slow | Medium | Fast |

Variables and Types

Python variables are names bound to objects. No type declarations - the type belongs to the object, not the variable.

| Type | Example |

|---|---|

int |

42, -7 |

float |

3.14, 1e-5 |

str |

"hello" |

bool |

True, False |

None |

None |

Naming conventions:

snake_case- variables, functionsPascalCase- classesUPPER_CASE- constants

Multiple assignment and swap:

Strings and Formatting

Strings are immutable sequences of characters. f-strings (formatted string literals) are the modern way to build strings with embedded values.

Common format specifiers:

| Specifier | Output | Use case |

|---|---|---|

:.2f |

0.94 |

Fixed decimals |

:.2% |

94.23% |

Percentages |

:, |

1,000 |

Thousands separator |

:>10 |

hello |

Right-align, width 10 |

:.2e |

9.42e-01 |

Scientific notation |

Collections Overview

Python provides four core collection types, each with different performance characteristics:

| Type | Syntax | Mutable | Ordered | Duplicates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| list | [1, 2, 3] |

Yes | Yes | Yes |

| tuple | (1, 2, 3) |

No | Yes | Yes |

| dict | {"a": 1} |

Yes | Yes* | Keys: No |

| set | {1, 2, 3} |

Yes | No | No |

*Dicts preserve insertion order (Python 3.7+)

Choosing the right collection:

- Need to modify elements? → list

- Fixed record (x, y, z)? → tuple

- Lookup by key? → dict

- Need unique values / fast membership? → set

Time complexity:

| Operation | list | dict | set |

|---|---|---|---|

Index x[i] |

O(1) | — | — |

Lookup x in |

O(n) | O(1) | O(1) |

| Append | O(1)* | — | O(1)* |

| Insert at i | O(n) | — | — |

| Delete | O(n) | O(1) | O(1) |

*Amortized — occasional resize is O(n)

Key insight: Use set or dict when you need fast in checks. Lists require scanning every element.

Lists: Mutable Sequences

Lists are ordered, mutable, and heterogeneous (can mix types).

layers = [64, 128, 256]

# Modify in place

layers.append(512) # Add to end

layers.insert(0, 32) # Insert at index

layers.extend([1024]) # Add multiple

print(f"After additions: {layers}")

# Remove elements

layers.pop() # Remove last

layers.remove(128) # Remove by value

print(f"After removals: {layers}")

# Sort and reverse

layers.sort() # In-place sort

print(f"Sorted: {layers}")

layers.reverse() # In-place reverse

print(f"Reversed: {layers}")After additions: [32, 64, 128, 256, 512, 1024]

After removals: [32, 64, 256, 512]

Sorted: [32, 64, 256, 512]

Reversed: [512, 256, 64, 32]List methods summary:

| Method | Effect | Returns |

|---|---|---|

append(x) |

Add to end | None |

extend(iter) |

Add all from iterable | None |

insert(i, x) |

Insert at index | None |

pop(i=-1) |

Remove at index | The element |

remove(x) |

Remove first occurrence | None |

sort() |

Sort in place | None |

reverse() |

Reverse in place | None |

copy() |

Shallow copy | New list |

index(x) |

Find index of x | int |

count(x) |

Count occurrences | int |

Note: Most methods modify the list in place and return None. Don’t write layers = layers.sort() — that sets layers to None.

Tuples: Immutable Sequences

Tuples are fixed-size, immutable sequences. Use them for records, multiple return values, and dict keys.

# Creating tuples

point = (3, 4)

rgb = (255, 128, 0)

single = (42,) # Note the comma!

empty = ()

# Unpacking

x, y = point

r, g, b = rgb

print(f"Point: x={x}, y={y}")

# Unpacking with * (rest)

first, *rest = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

print(f"First: {first}, Rest: {rest}")

# Swapping uses tuple packing/unpacking

a, b = 1, 2

a, b = b, a # Swap!

print(f"Swapped: a={a}, b={b}")Point: x=3, y=4

First: 1, Rest: [2, 3, 4, 5]

Swapped: a=2, b=1Why use tuples?

- Immutability as documentation — signals “don’t modify”

- Hashable — can be dict keys or set elements

- Slightly faster — no over-allocation overhead

- Multiple return values

def minmax(data):

"""Return (min, max) tuple."""

return min(data), max(data)

lo, hi = minmax([3, 1, 4, 1, 5, 9])

print(f"Range: {lo} to {hi}")

# Named tuples for clarity

from collections import namedtuple

Point = namedtuple('Point', ['x', 'y'])

p = Point(3, 4)

print(f"Point: {p.x}, {p.y}")

print(f"Distance: {(p.x**2 + p.y**2)**0.5:.2f}")Range: 1 to 9

Point: 3, 4

Distance: 5.00Dictionaries: Key-Value Mapping

Dicts map keys to values with O(1) average lookup. Keys must be hashable (immutable).

config = {

"learning_rate": 0.001,

"epochs": 100,

"batch_size": 32,

}

# Access and modify

print(f"LR: {config['learning_rate']}")

config["dropout"] = 0.5

config["epochs"] = 200

# Safe access with .get()

momentum = config.get("momentum", 0.9)

print(f"Momentum: {momentum}")

# Iteration

print("\nAll settings:")

for key, value in config.items():

print(f" {key}: {value}")LR: 0.001

Momentum: 0.9

All settings:

learning_rate: 0.001

epochs: 200

batch_size: 32

dropout: 0.5Dict methods:

| Method | Returns |

|---|---|

d[key] |

Value (raises KeyError if missing) |

d.get(key, default) |

Value or default |

d.keys() |

View of keys |

d.values() |

View of values |

d.items() |

View of (key, value) pairs |

d.pop(key) |

Remove and return value |

d.update(other) |

Merge another dict |

key in d |

Membership test (O(1)) |

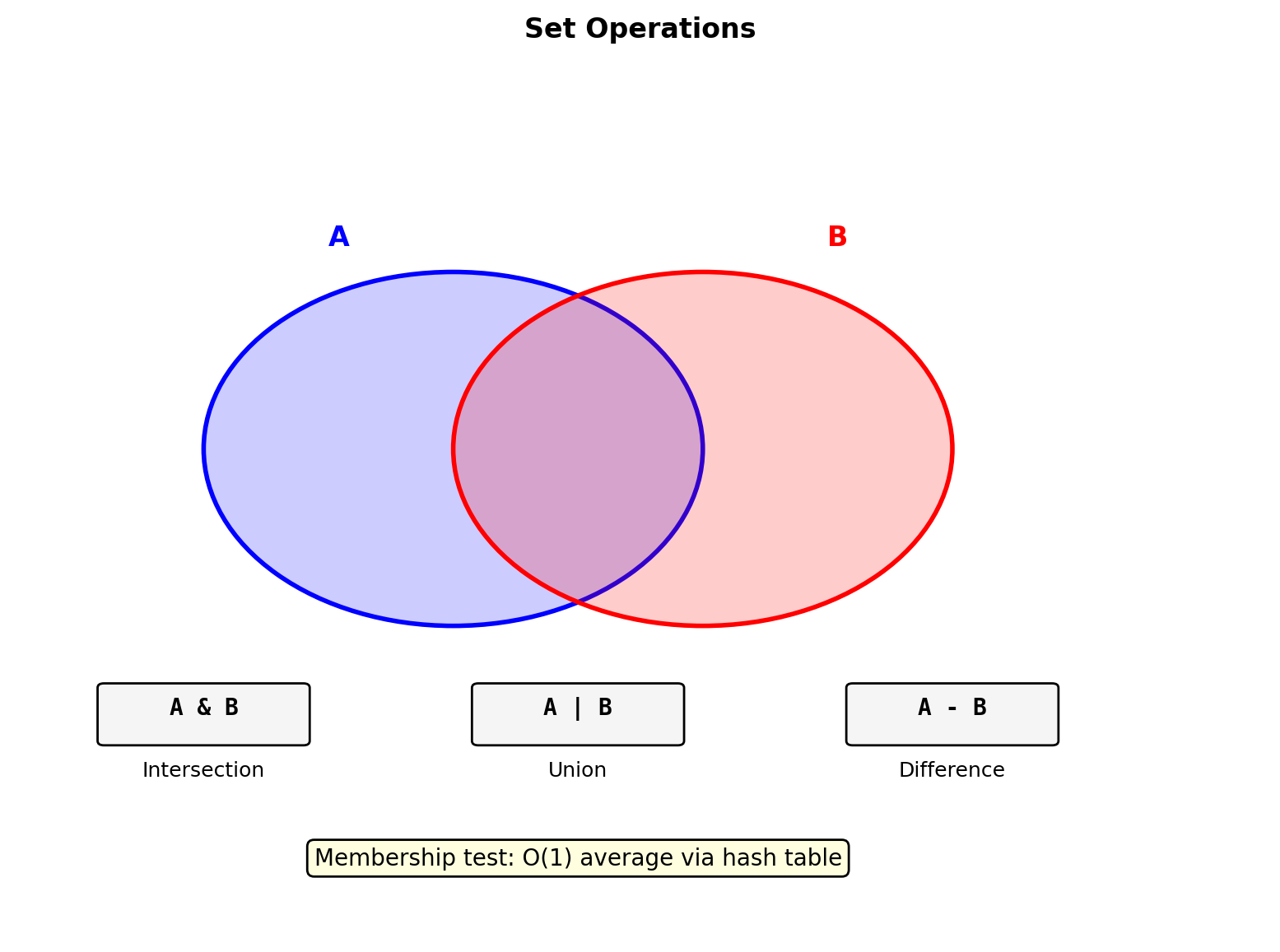

Sets: Unique Elements

Sets store unique elements with O(1) membership testing. Based on hash tables like dicts.

# Creating sets

seen_labels = {0, 1, 2, 1, 0} # Duplicates removed

print(f"Unique labels: {seen_labels}")

# From list (common pattern)

data = [1, 2, 2, 3, 3, 3]

unique = set(data)

print(f"Unique values: {unique}")

print(f"Count: {len(unique)}")

# Membership testing (fast!)

if 2 in seen_labels:

print("Label 2 exists")

# Set operations

a = {1, 2, 3, 4}

b = {3, 4, 5, 6}

print(f"Union: {a | b}")

print(f"Intersection: {a & b}")

print(f"Difference: {a - b}")

print(f"Symmetric diff: {a ^ b}")Unique labels: {0, 1, 2}

Unique values: {1, 2, 3}

Count: 3

Label 2 exists

Union: {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6}

Intersection: {3, 4}

Difference: {1, 2}

Symmetric diff: {1, 2, 5, 6}When to use sets:

# Finding duplicates

items = ["cat", "dog", "cat", "bird", "dog"]

seen = set()

duplicates = set()

for item in items:

if item in seen:

duplicates.add(item)

seen.add(item)

print(f"Duplicates: {duplicates}")Duplicates: {'cat', 'dog'}Set vs list for membership:

import timeit

data_list = list(range(10000))

data_set = set(range(10000))

t_list = timeit.timeit(lambda: 9999 in data_list, number=1000)

t_set = timeit.timeit(lambda: 9999 in data_set, number=1000)

print(f"List lookup: {t_list*1000:.2f}ms")

print(f"Set lookup: {t_set*1000:.2f}ms")

print(f"Set is {t_list/t_set:.0f}x faster")List lookup: 57.76ms

Set lookup: 0.03ms

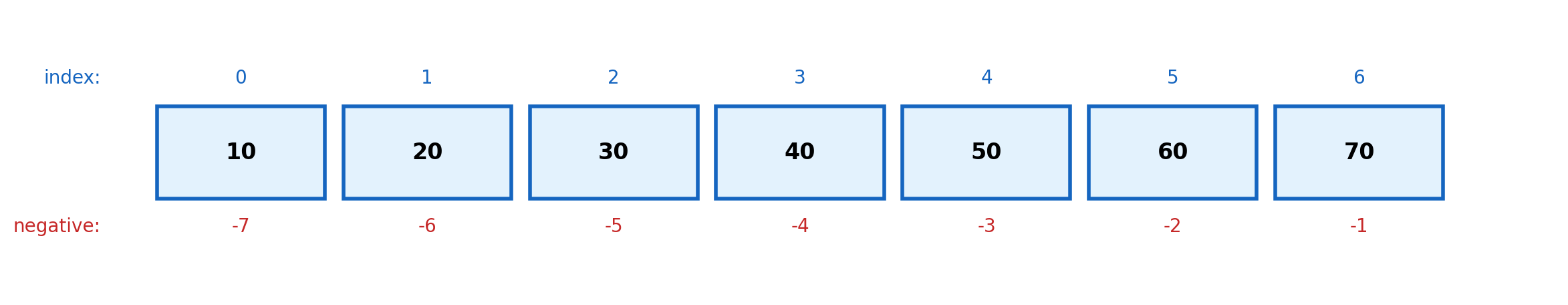

Set is 2051x fasterIndexing and Slicing

Zero-based indexing. Negative indices count from the end. Slicing creates copies.

Slice syntax: [start:stop:step]

start: First index (inclusive), default 0stop: Last index (exclusive), default lenstep: Increment, default 1

data = [10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70]

print(f"data[2:5] = {data[2:5]}") # [30, 40, 50]

print(f"data[:3] = {data[:3]}") # [10, 20, 30]

print(f"data[4:] = {data[4:]}") # [50, 60, 70]

print(f"data[::2] = {data[::2]}") # [10, 30, 50, 70]

print(f"data[::-1] = {data[::-1]}") # Reversed

print(f"data[1:-1] = {data[1:-1]}") # [20, 30, 40, 50, 60]data[2:5] = [30, 40, 50]

data[:3] = [10, 20, 30]

data[4:] = [50, 60, 70]

data[::2] = [10, 30, 50, 70]

data[::-1] = [70, 60, 50, 40, 30, 20, 10]

data[1:-1] = [20, 30, 40, 50, 60]Slicing creates copies (for lists):

original = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

copy = original[:] # Shallow copy

copy[0] = 999

print(f"Original: {original}")

print(f"Copy: {copy}")Original: [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

Copy: [999, 2, 3, 4, 5]Slice assignment (modifies in place):

data = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

data[1:4] = [20, 30] # Replace slice

print(f"After: {data}")

data[2:2] = [100, 200] # Insert at index 2

print(f"After insert: {data}")After: [1, 20, 30, 5]

After insert: [1, 20, 100, 200, 30, 5]Warning: NumPy arrays behave differently — slices are views, not copies.

Conditionals and Boolean Logic

Python uses indentation (not braces) to define blocks. Standard is 4 spaces.

score = 0.85

if score >= 0.9:

grade = "A"

elif score >= 0.8:

grade = "B"

elif score >= 0.7:

grade = "C"

else:

grade = "F"

print(grade)BConditional expression (ternary):

Boolean operators use words, not symbols:

| Python | C/Java equivalent |

|---|---|

and |

&& |

or |

\|\| |

not |

! |

Short-circuit evaluation: and/or stop as soon as result is determined.

# Second part not evaluated if first is False

x = None

if x is not None and x > 0:

print("Positive")

else:

print("None or non-positive")None or non-positiveChained comparisons (Python-specific):

Truthiness and Falsy Values

Python evaluates any object in boolean context. Falsy values evaluate to False; everything else is truthy.

Falsy values (memorize these):

| Type | Falsy value |

|---|---|

| Boolean | False |

| None | None |

| Numeric zero | 0, 0.0, 0j, Decimal(0) |

| Empty sequence | "", [], () |

| Empty mapping | {} |

| Empty set | set() |

Everything else is truthy: non-zero numbers, non-empty strings, non-empty collections, objects.

Idiomatic patterns using truthiness:

data = []

# Instead of: if len(data) > 0:

if data:

print("Has items")

else:

print("Empty")

# Default value pattern

name = ""

display_name = name or "Anonymous"

print(f"Hello, {display_name}")

# Guard clause

result = None

value = result or "default"

print(value)Empty

Hello, Anonymous

defaultCaution with or: Returns first truthy value or last value, not necessarily True/False.

For Loops and Iteration

Python’s for iterates over iterables (sequences, generators, files, etc.), not indices. This is fundamentally different from C-style for (i=0; i<n; i++).

Basic iteration:

range() for numeric sequences:

# range(stop), range(start, stop), range(start, stop, step)

print(list(range(5))) # [0, 1, 2, 3, 4]

print(list(range(2, 6))) # [2, 3, 4, 5]

print(list(range(0, 10, 2))) # [0, 2, 4, 6, 8][0, 1, 2, 3, 4]

[2, 3, 4, 5]

[0, 2, 4, 6, 8]range() is lazy — yields values on demand, doesn’t create a list. range(10**9) uses ~48 bytes, not 8 GB.

enumerate() when you need indices:

zip() for parallel iteration:

names = ["Alice", "Bob", "Carol"]

scores = [85, 92, 78]

for name, score in zip(names, scores):

print(f"{name}: {score}")Alice: 85

Bob: 92

Carol: 78Loop control:

| Statement | Effect |

|---|---|

break |

Exit loop immediately |

continue |

Skip to next iteration |

else |

Runs if loop completes without break |

While Loops

Use while when the number of iterations isn’t known in advance, or for event loops.

# Convergence loop (common in optimization)

loss = 1.0

iteration = 0

tolerance = 0.1

while loss > tolerance:

loss *= 0.5

iteration += 1

print(f"Converged in {iteration} iterations")

print(f"Final loss: {loss:.4f}")Converged in 4 iterations

Final loss: 0.0625Infinite loop with break:

for vs while:

for |

while |

|---|---|

| Iterating over a collection | Unknown iteration count |

| Known iteration count | Waiting for condition |

| Processing each element | Event loops |

Infinite loop (loop variable not updated):

Off-by-one (<= vs <):

The walrus operator (:=, Python 3.8+):

Comprehensions

Comprehensions are concise, readable syntax for creating collections from iteration. They replace common for loop patterns.

General form:

[expression for item in iterable if condition]List comprehension:

# Transform each element

squares = [x**2 for x in range(6)]

print(squares)

# Filter elements

evens = [x for x in range(10) if x % 2 == 0]

print(evens)

# Equivalent explicit loop:

# evens = []

# for x in range(10):

# if x % 2 == 0:

# evens.append(x)[0, 1, 4, 9, 16, 25]

[0, 2, 4, 6, 8]Nested comprehension:

Dict and set comprehensions:

# Dict: {key_expr: value_expr for ...}

words = ["cat", "dog", "elephant"]

lengths = {w: len(w) for w in words}

print(lengths)

# Set: {expr for ...}

remainders = {x % 3 for x in range(10)}

print(remainders){'cat': 3, 'dog': 3, 'elephant': 8}

{0, 1, 2}Generator expression (lazy, memory-efficient):

# Parentheses instead of brackets

gen = (x**2 for x in range(1000000))

print(type(gen))

print(sum(gen)) # Computed on-demand<class 'generator'>

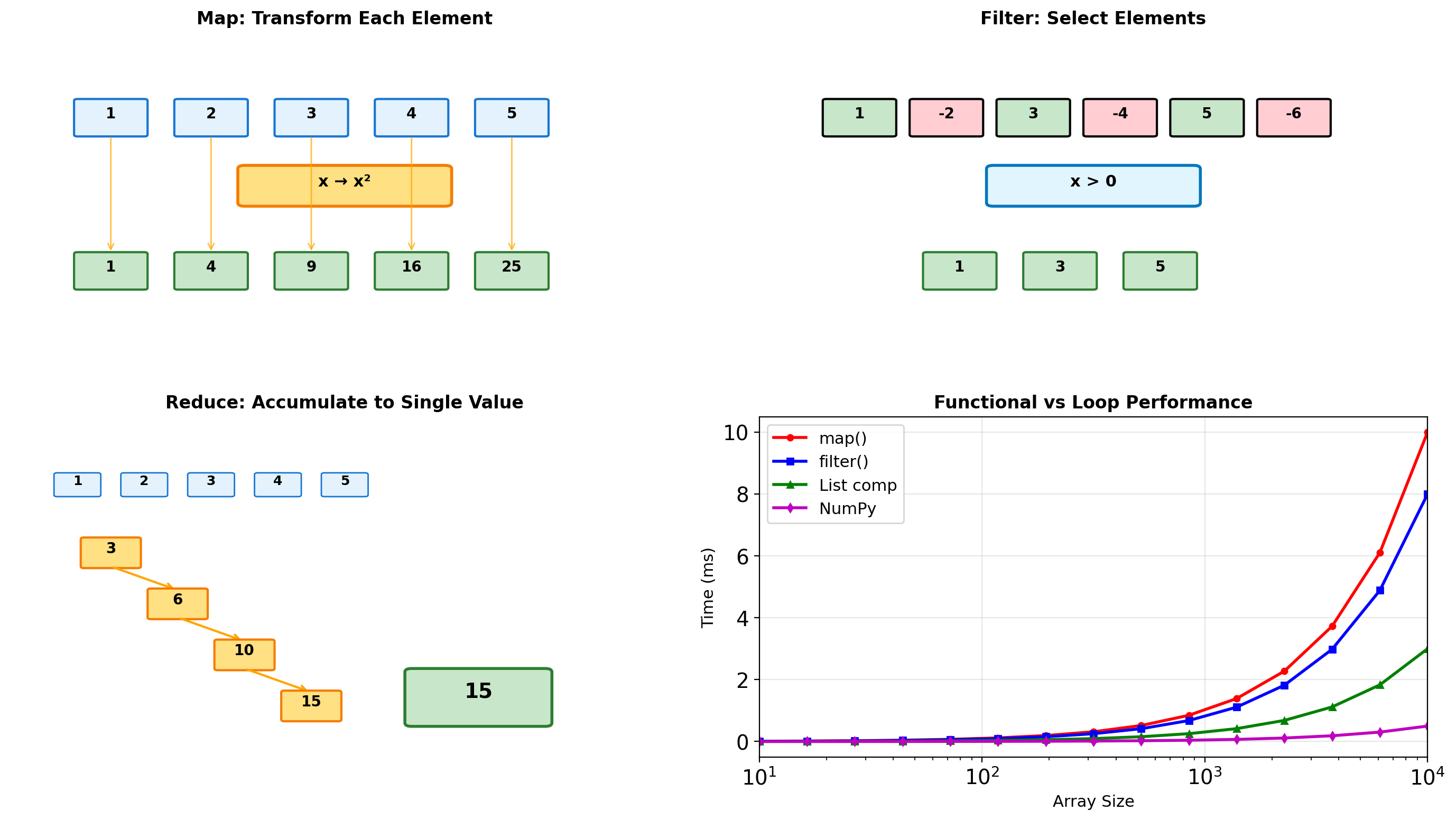

333332833333500000Performance: Comprehensions are ~10-20% faster than equivalent for loops (append is inlined in bytecode).

Defining Functions

Functions are defined with def. The first string literal becomes __doc__ (accessible via help()).

def compute_accuracy(correct, total):

"""Compute classification accuracy."""

return correct / total

print(compute_accuracy(85, 100))0.85Function structure:

- No return type declaration

- No

returnstatement → returnsNone - Functions are objects (can be assigned, passed, returned)

Function Arguments

Positional vs keyword:

def train(model, lr, epochs):

print(f"model={model}, lr={lr}, epochs={epochs}")

train("resnet", 0.01, 100) # Positional

train("resnet", epochs=50, lr=0.001) # Keyword (any order)

train("resnet", 0.01, epochs=200) # Mixedmodel=resnet, lr=0.01, epochs=100

model=resnet, lr=0.001, epochs=50

model=resnet, lr=0.01, epochs=200Variadic arguments:

| Syntax | Captures |

|---|---|

*args |

Extra positional → tuple |

**kwargs |

Extra keyword → dict |

def log_call(name, *args, **kwargs):

print(f"Function: {name}")

print(f" args: {args}")

print(f" kwargs: {kwargs}")

log_call("train", 100, 0.01, lr=0.001, verbose=True)Function: train

args: (100, 0.01)

kwargs: {'lr': 0.001, 'verbose': True}Argument order in signature:

- Regular positional

*args- Keyword-only (after

*) **kwargs

Mutable Default Arguments

Default values are evaluated once at function definition, not per call.

Shared mutable default:

Classes

Classes bundle data (attributes) with behavior (methods).

class Layer:

def __init__(self, in_size, out_size):

self.in_size = in_size

self.out_size = out_size

def num_params(self):

return self.in_size * self.out_size + self.out_size

def __repr__(self):

return f"Layer({self.in_size}, {self.out_size})"

layer = Layer(784, 256)

print(layer)

print(f"Parameters: {layer.num_params():,}")Layer(784, 256)

Parameters: 200,960Special methods (dunder methods):

| Method | Called by |

|---|---|

__init__ |

Layer(...) (constructor) |

__repr__ |

repr(obj), debugger display |

__str__ |

str(obj), print(obj) |

__len__ |

len(obj) |

__getitem__ |

obj[key] |

__call__ |

obj(...) (callable) |

self: Explicit reference to instance (like this in C++/Java, but explicit in signature).

Attributes: Created by assignment to self.name — no declaration needed.

Modules and Imports

Module = Python file. Package = directory with __init__.py.

Import styles:

import math # Entire module

print(math.sqrt(2))

import numpy as np # Alias

from collections import Counter # Specific name

print(Counter("abracadabra"))1.4142135623730951

Counter({'a': 5, 'b': 2, 'r': 2, 'c': 1, 'd': 1})| Style | Access | Namespace |

|---|---|---|

import mod |

mod.func() |

Separate |

import mod as m |

m.func() |

Aliased |

from mod import func |

func() |

Merged |

from mod import * |

All names | Pollutes (avoid) |

Exception Handling

try/except structure:

def safe_divide(a, b):

try:

return a / b

except ZeroDivisionError:

return float('inf')

print(safe_divide(10, 2))

print(safe_divide(10, 0))5.0

infCatching with details:

Full syntax:

try:

risky_operation()

except ValueError as e:

handle_value_error(e)

except (TypeError, KeyError):

handle_other()

else:

# Runs if no exception

success()

finally:

# Always runs (cleanup)

close_resources()Raising exceptions:

Common exceptions:

| Exception | Cause |

|---|---|

ValueError |

Wrong value |

TypeError |

Wrong type |

KeyError |

Missing dict key |

IndexError |

Index out of range |

AttributeError |

Missing attribute |

Built-in Functions

Aggregation:

| Function | Description |

|---|---|

len(x) |

Length/size |

sum(x) |

Sum elements |

min(x), max(x) |

Minimum/maximum |

sorted(x) |

Sorted copy |

reversed(x) |

Reverse iterator |

Type operations:

| Function | Description |

|---|---|

type(x) |

Type of object |

isinstance(x, t) |

Type check |

int(), float(), str() |

Conversion |

list(), tuple(), set() |

Collection conversion |

Boolean:

| Function | Description |

|---|---|

any(x) |

True if any truthy |

all(x) |

True if all truthy |

bool(x) |

Convert to boolean |

Numeric:

| Function | Description |

|---|---|

abs(x) |

Absolute value |

round(x, n) |

Round to n decimals |

pow(x, y) |

x^y (or x ** y) |

divmod(a, b) |

(a // b, a % b) |

Iteration:

| Function | Description |

|---|---|

range(n) |

0, 1, …, n-1 |

enumerate(x) |

(index, value) pairs |

zip(a, b) |

Parallel iteration |

map(f, x) |

Apply f to each |

filter(f, x) |

Keep where f(x) true |

Type Hints

Type hints document expected types. Not enforced at runtime — for documentation and static analysis (mypy).

Syntax (Python 3.10+):

| Type | Meaning |

|---|---|

int, float, str |

Basic types |

list[int] |

List of ints |

dict[str, float] |

Dict with str keys |

tuple[int, str] |

Fixed-length tuple |

int \| None |

Union (or Optional[int]) |

Callable[[int], str] |

Function type |

Any |

Disable type checking |

Checking with mypy:

Benefits: IDE autocompletion, catch type errors before runtime, self-documenting signatures.

Data Structure Internals

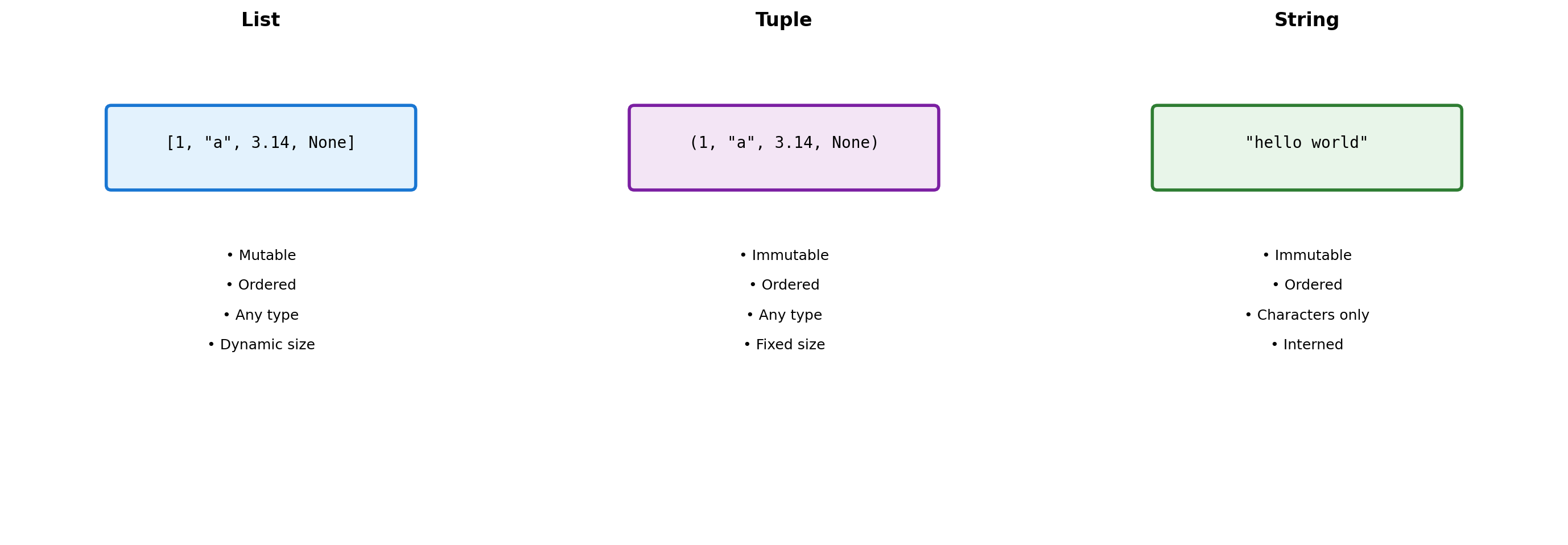

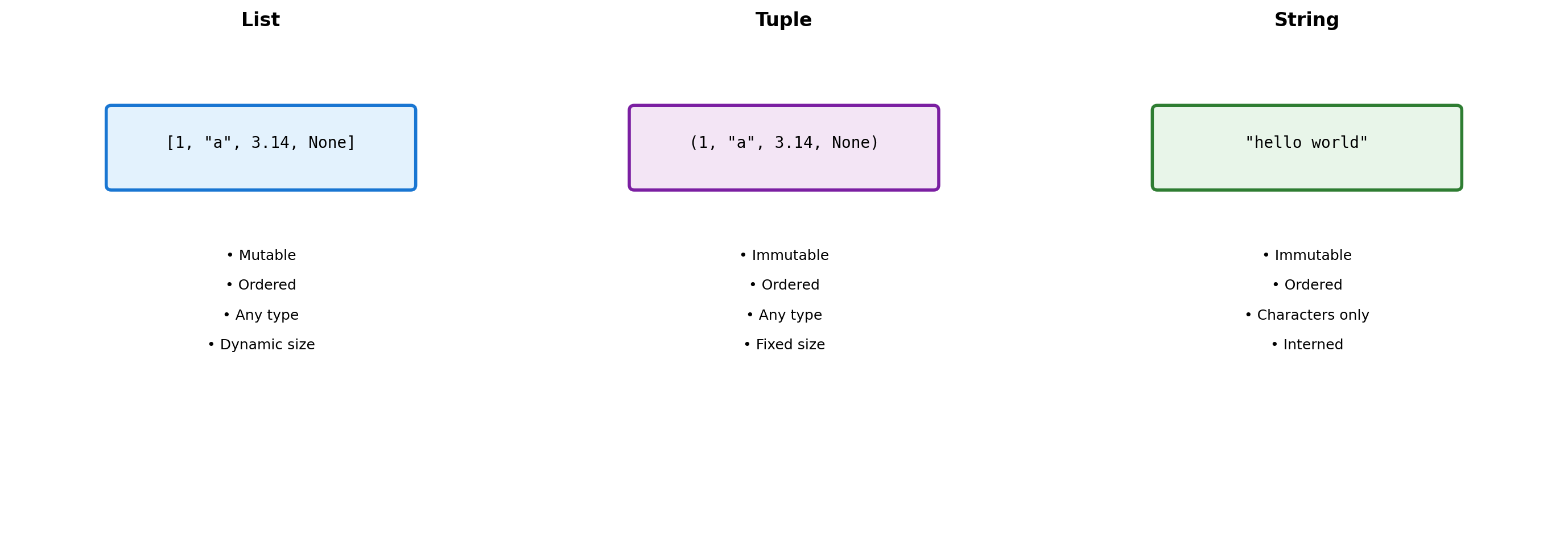

Sequence Types: Three Design Choices

Python provides three sequence types with different trade-offs.

Design Consequences:

- Lists allow heterogeneous data but pay indirection cost

- Tuples trade mutability for hashability and memory efficiency

- Strings optimize for text with specialized methods

import sys

# Memory comparison

lst = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

tup = (1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

string = "12345"

print("Memory usage:")

print(f" List: {sys.getsizeof(lst)} bytes")

print(f" Tuple: {sys.getsizeof(tup)} bytes")

print(f" String: {sys.getsizeof(string)} bytes")

# Hashability determines dict key eligibility

print("\nCan be dict key:")

for obj, name in [(lst, 'List'), (tup, 'Tuple'), (string, 'String')]:

try:

d = {obj: 'value'}

print(f" {name}: Yes")

except TypeError:

print(f" {name}: No")Memory usage:

List: 104 bytes

Tuple: 80 bytes

String: 54 bytes

Can be dict key:

List: No

Tuple: Yes

String: YesList Internals: Over-allocation Strategy

Lists allocate extra space to amortize the cost of growth.

# Observe allocation behavior

import sys

lst = []

sizes_and_caps = []

for i in range(20):

lst.append(i)

# Size includes list object overhead

total_size = sys.getsizeof(lst)

# Approximate capacity from size

capacity = (total_size - sys.getsizeof([])) // 8

sizes_and_caps.append((len(lst), capacity))

# Show growth points

print("Size → Capacity:")

last_cap = 0

for size, cap in sizes_and_caps:

if cap != last_cap:

print(f" {size:2d} → {cap:2d} (grew by {cap - last_cap})")

last_cap = capSize → Capacity:

1 → 4 (grew by 4)

5 → 8 (grew by 4)

9 → 16 (grew by 8)

17 → 24 (grew by 8)Growth Strategy:

When a list exceeds capacity, Python:

- Calculates new capacity using formula

- Allocates new pointer array

- Copies all existing pointers

- Frees old array

Cost Analysis:

- Append is O(1) amortized

- Individual append can trigger O(n) reallocation

- Trade memory for performance

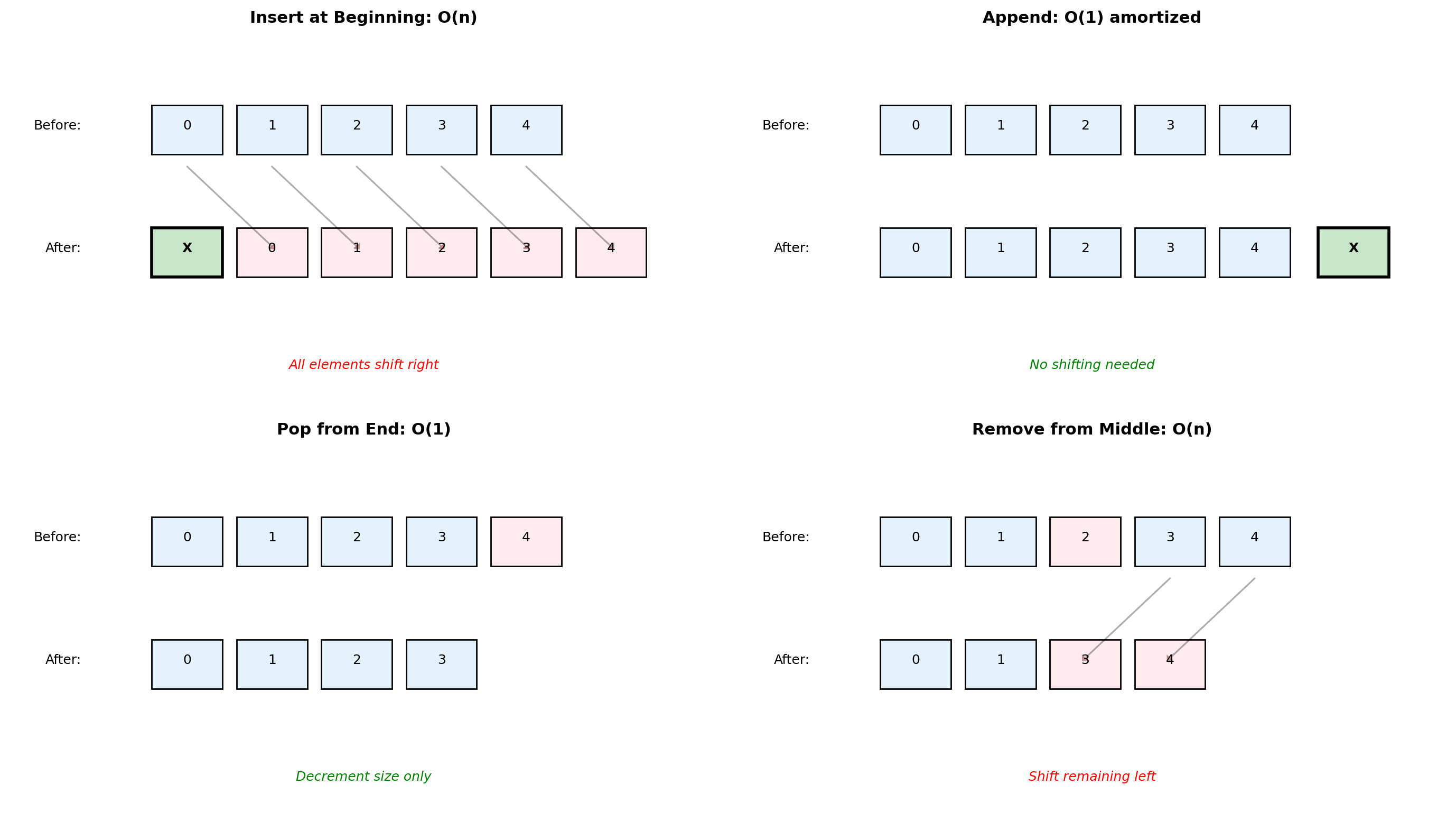

List Operations: Implementation Details

Different operations have different costs based on internal structure.

# Demonstrating operation costs

import time

def measure_operation(lst, operation, description):

"""Measure single operation time."""

start = time.perf_counter()

operation(lst)

elapsed = time.perf_counter() - start

return elapsed * 1e6 # Convert to microseconds

# Large list for measurable times

n = 100000

test_list = list(range(n))

# Operations

times = {}

times['append'] = measure_operation(test_list.copy(),

lambda l: l.append(999),

"Append")

times['insert_0'] = measure_operation(test_list.copy(),

lambda l: l.insert(0, 999),

"Insert at 0")

times['pop'] = measure_operation(test_list.copy(),

lambda l: l.pop(),

"Pop from end")

times['pop_0'] = measure_operation(test_list.copy(),

lambda l: l.pop(0),

"Pop from start")

print(f"Operation times (n={n}):")

for op, time in times.items():

print(f" {op:12s}: {time:8.2f} μs")Operation times (n=100000):

append : 0.79 μs

insert_0 : 31.33 μs

pop : 0.33 μs

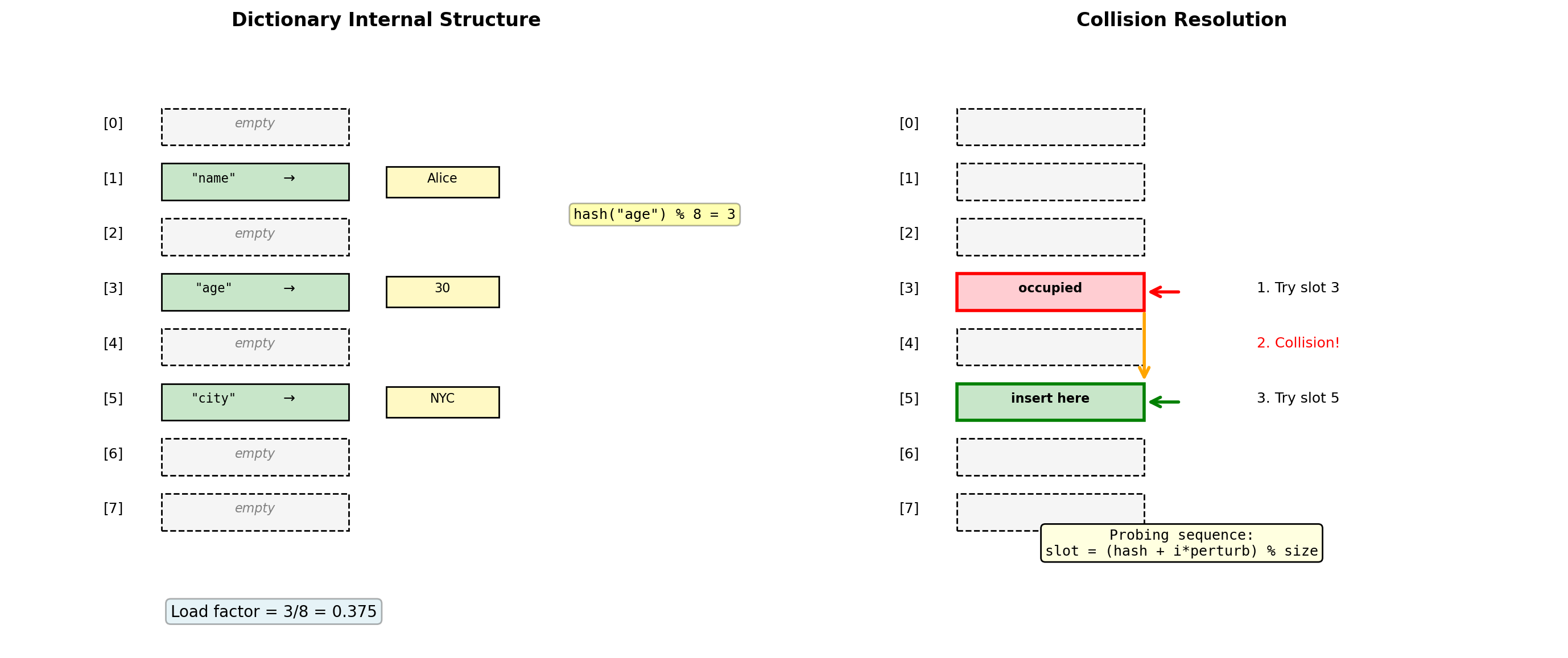

pop_0 : 14.33 μsDictionary Architecture: Open Addressing Hash Table

Dictionaries use open addressing with random probing for collision resolution.

# Dictionary internals

d = {'a': 1, 'b': 2, 'c': 3}

# Show hash values

for key in d:

print(f"hash('{key}') = {hash(key):20d}")

# Dictionary growth

import sys

sizes = []

for i in range(20):

d = {str(j): j for j in range(i)}

sizes.append((i, sys.getsizeof(d)))

print("\nDict size growth:")

last_size = 0

for n, size in sizes:

if size != last_size:

print(f" {n:2d} items: {size:4d} bytes")

last_size = sizehash('a') = -8650723016916319182

hash('b') = 6464835138523459154

hash('c') = 1984612578382285418

Dict size growth:

0 items: 64 bytes

1 items: 184 bytes

6 items: 272 bytes

11 items: 464 bytesDesign Choices:

- Open addressing: No separate chains, better cache locality

- 2/3 load factor: Resize when 2/3 full

- Perturbed probing: Reduces clustering

- Cached hash values: Store hash with key to avoid recomputation

Consequences:

- O(1) average case for all operations

- Order preserved since Python 3.7

- More memory than theoretical minimum

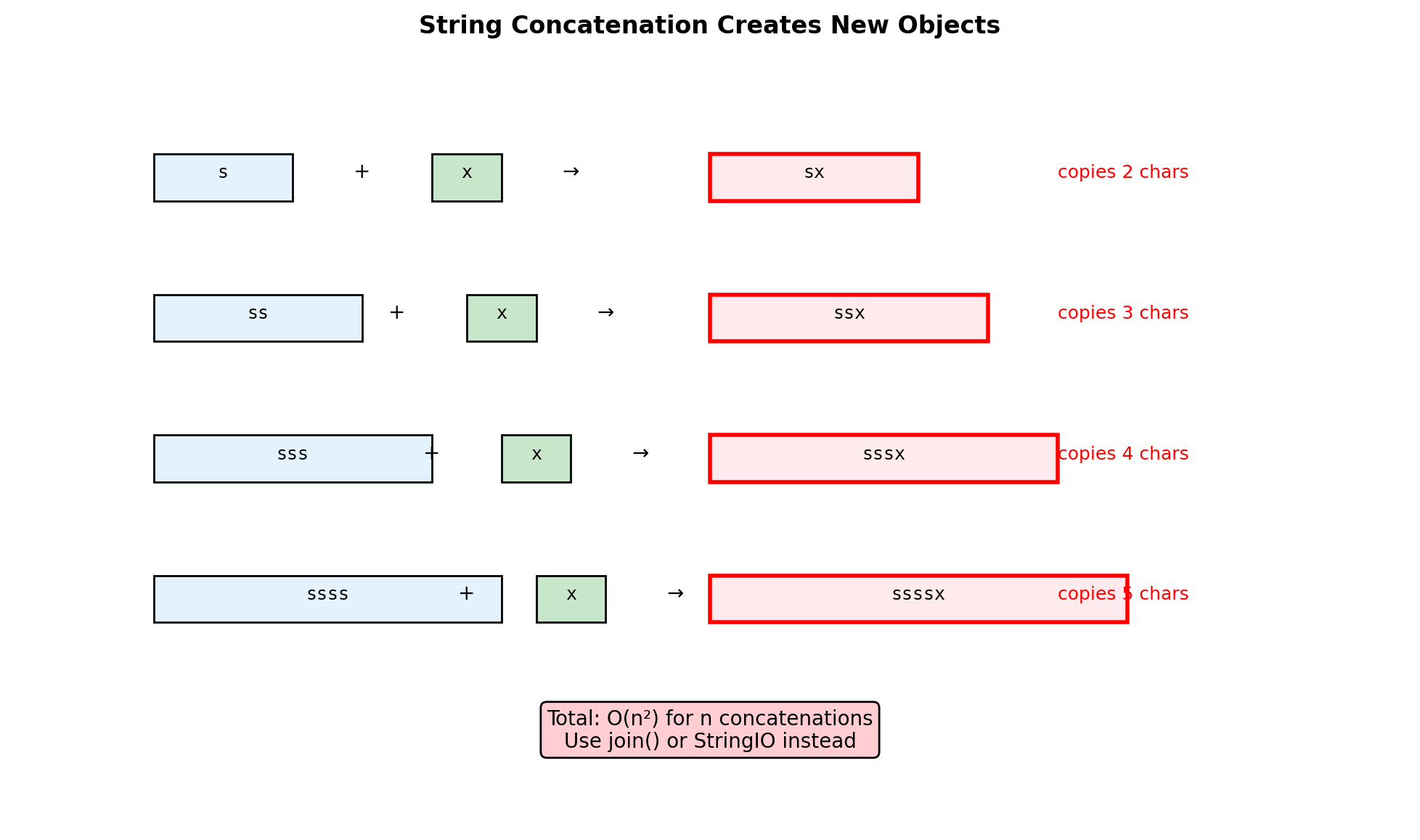

String Building: Algorithmic Complexity

Building strings efficiently requires understanding concatenation costs.

import io

import timeit

n = 1000

chunk = "x" * 10

# Method 1: Repeated concatenation (BAD)

def build_concat():

s = ""

for _ in range(n):

s += chunk # Creates new string each time

return s

# Method 2: Join (GOOD)

def build_join():

parts = []

for _ in range(n):

parts.append(chunk)

return "".join(parts)

# Method 3: StringIO (GOOD)

def build_io():

buffer = io.StringIO()

for _ in range(n):

buffer.write(chunk)

return buffer.getvalue()

# Compare performance

t1 = timeit.timeit(build_concat, number=100)

t2 = timeit.timeit(build_join, number=100)

t3 = timeit.timeit(build_io, number=100)

print(f"Building {n}-chunk string (100 iterations):")

print(f" Concatenation: {t1:.4f}s")

print(f" Join: {t2:.4f}s ({t1/t2:.1f}x faster)")

print(f" StringIO: {t3:.4f}s ({t1/t3:.1f}x faster)")Building 1000-chunk string (100 iterations):

Concatenation: 0.0035s

Join: 0.0017s (2.1x faster)

StringIO: 0.0029s (1.2x faster)Collection Internals: Sets and Frozen Sets

Sets use the same hash table technology as dictionaries, optimized for membership testing.

# Set performance demonstration

import random

# Create test data

numbers = list(range(10000))

random.shuffle(numbers)

test_list = numbers[:5000]

test_set = set(test_list)

# Membership testing

lookups = random.sample(range(10000), 100)

import time

# List lookup

start = time.perf_counter()

for x in lookups:

_ = x in test_list

list_time = time.perf_counter() - start

# Set lookup

start = time.perf_counter()

for x in lookups:

_ = x in test_set

set_time = time.perf_counter() - start

print(f"100 lookups in collection of 5000:")

print(f" List: {list_time*1000:.3f} ms")

print(f" Set: {set_time*1000:.3f} ms")

print(f" Speedup: {list_time/set_time:.1f}x")

# Set operations

a = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

b = {4, 5, 6, 7, 8}

print(f"\nSet operations:")

print(f" a & b = {a & b}") # Intersection

print(f" a | b = {a | b}") # Union

print(f" a - b = {a - b}") # Difference

print(f" a ^ b = {a ^ b}") # Symmetric difference100 lookups in collection of 5000:

List: 2.265 ms

Set: 0.024 ms

Speedup: 96.0x

Set operations:

a & b = {4, 5}

a | b = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8}

a - b = {1, 2, 3}

a ^ b = {1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 8}Set Implementation:

- Same hash table as dict (no values)

- Average O(1) for add, remove, membership

- Set operations optimized with early termination

- Frozen sets are immutable and hashable

When to use sets:

- Membership testing in loops

- Removing duplicates

- Mathematical set operations

- When order doesn’t matter

Memory overhead:

- Minimum size: 8 slots

- Growth factor: 4x until 50k, then 2x

- ~30% more memory than list of same items

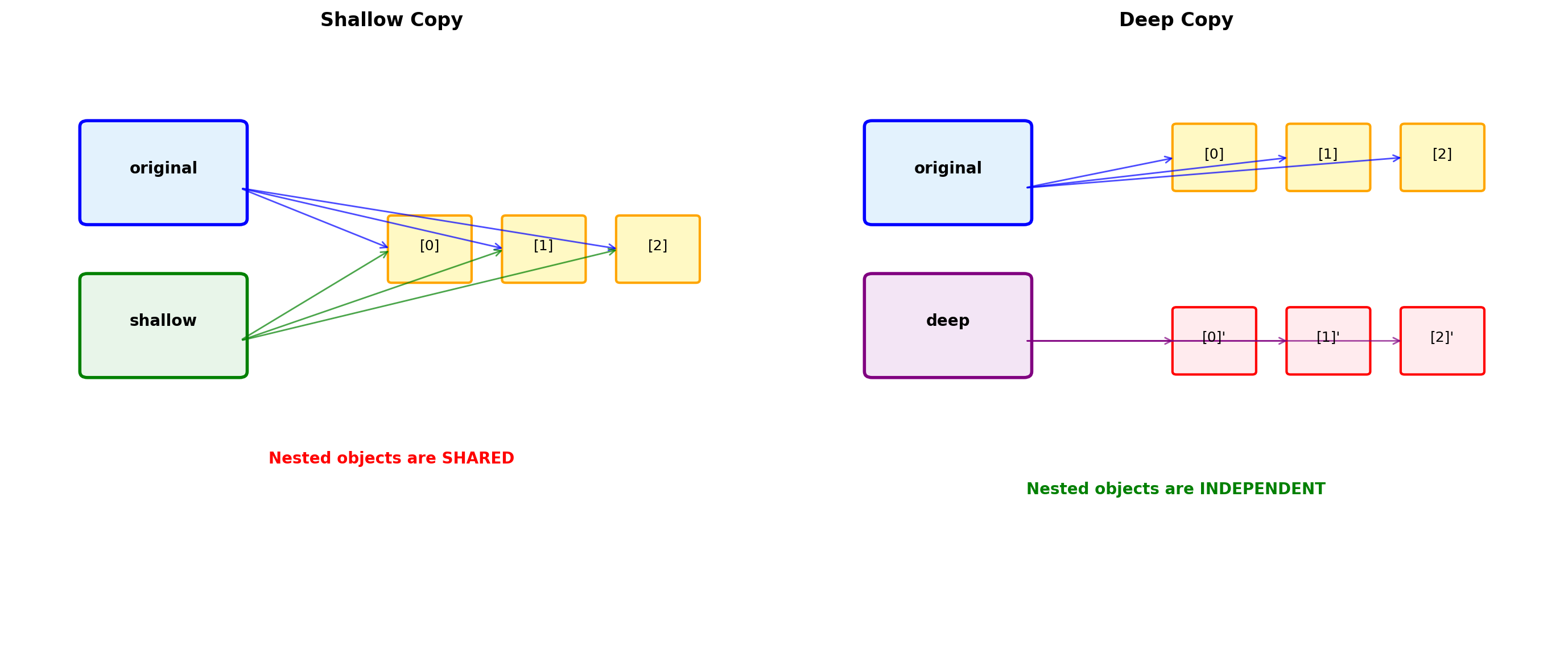

Shallow vs Deep Copying

Python’s default copying behavior can lead to unexpected aliasing.

import copy

# Create nested structure

original = [[1, 2], [3, 4], [5, 6]]

# Different copy methods

reference = original

shallow = original.copy() # or list(original) or original[:]

deep = copy.deepcopy(original)

# Modify nested object

original[0].append(3)

print("After modifying original[0]:")

print(f" original: {original}")

print(f" reference: {reference}") # Changed

print(f" shallow: {shallow}") # Changed!

print(f" deep: {deep}") # Unchanged

# Identity checks

print("\nIdentity comparisons:")

print(f" original is reference: {original is reference}")

print(f" original is shallow: {original is shallow}")

print(f" original[0] is shallow[0]: {original[0] is shallow[0]}") # True!

print(f" original[0] is deep[0]: {original[0] is deep[0]}") # FalseAfter modifying original[0]:

original: [[1, 2, 3], [3, 4], [5, 6]]

reference: [[1, 2, 3], [3, 4], [5, 6]]

shallow: [[1, 2, 3], [3, 4], [5, 6]]

deep: [[1, 2], [3, 4], [5, 6]]

Identity comparisons:

original is reference: True

original is shallow: False

original[0] is shallow[0]: True

original[0] is deep[0]: FalseAbstraction and Design

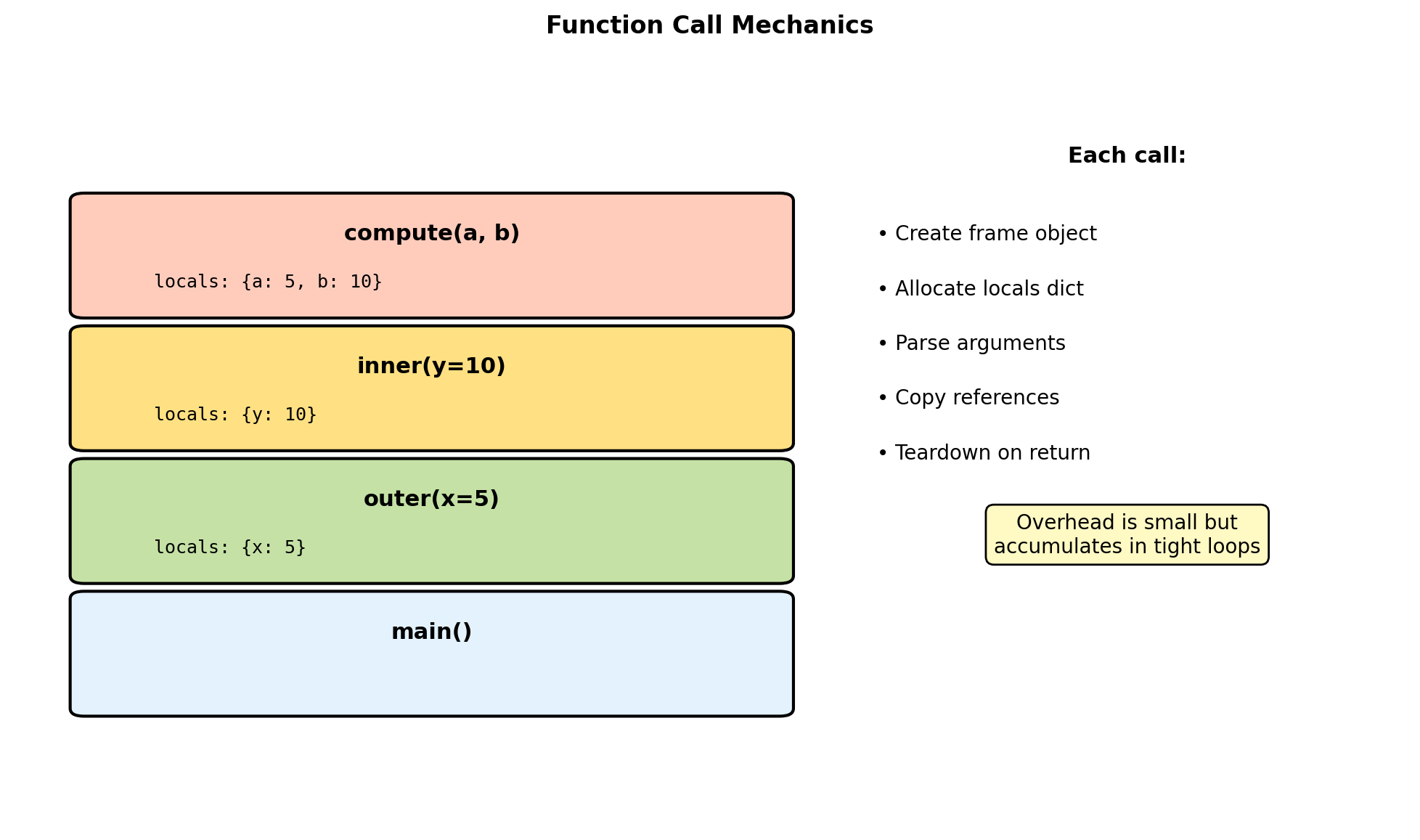

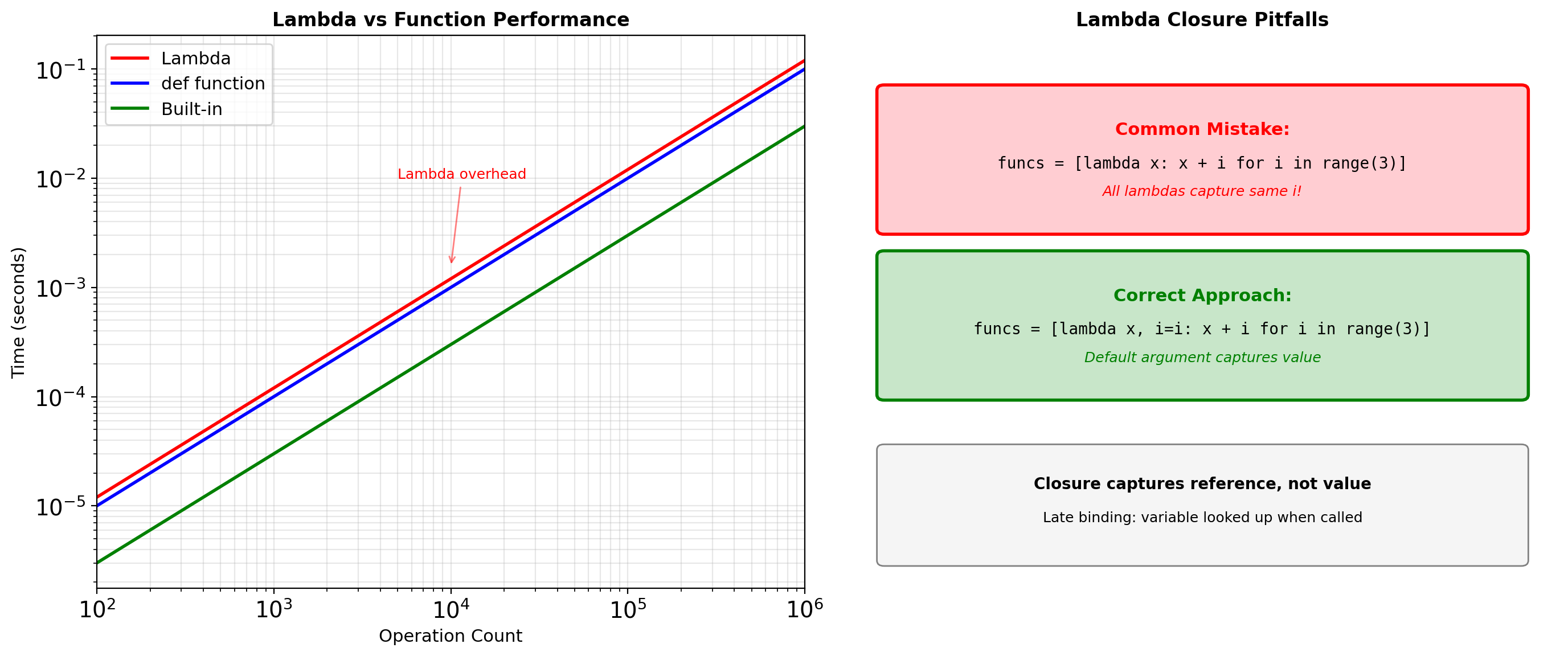

Function Call Overhead

import timeit

def add_function(x, y):

return x + y

add_lambda = lambda x, y: x + y

# Direct operation

def test_inline():

total = 0

for i in range(1000):

total += i + 1

return total

# Function call

def test_function():

total = 0

for i in range(1000):

total += add_function(i, 1)

return total

# Lambda call

def test_lambda():

total = 0

for i in range(1000):

total += add_lambda(i, 1)

return total

n = 10000

t_inline = timeit.timeit(test_inline, number=n)

t_func = timeit.timeit(test_function, number=n)

t_lambda = timeit.timeit(test_lambda, number=n)

print(f"1000 additions, {n} iterations:")

print(f" Inline: {t_inline:.3f}s")

print(f" Function: {t_func:.3f}s ({t_func/t_inline:.1f}x)")

print(f" Lambda: {t_lambda:.3f}s ({t_lambda/t_inline:.1f}x)")1000 additions, 10000 iterations:

Inline: 0.217s

Function: 0.346s (1.6x)

Lambda: 0.342s (1.6x)Call overhead includes:

- Frame object allocation (~100ns)

- Argument parsing and binding (~50ns)

- Namespace setup (~30ns)

- Exception context (~20ns)

Optimization strategies:

- Cache method lookups outside loops

- Use list comprehensions (C loop)

- Vectorize with NumPy

- Consider

@jitfor numerical code

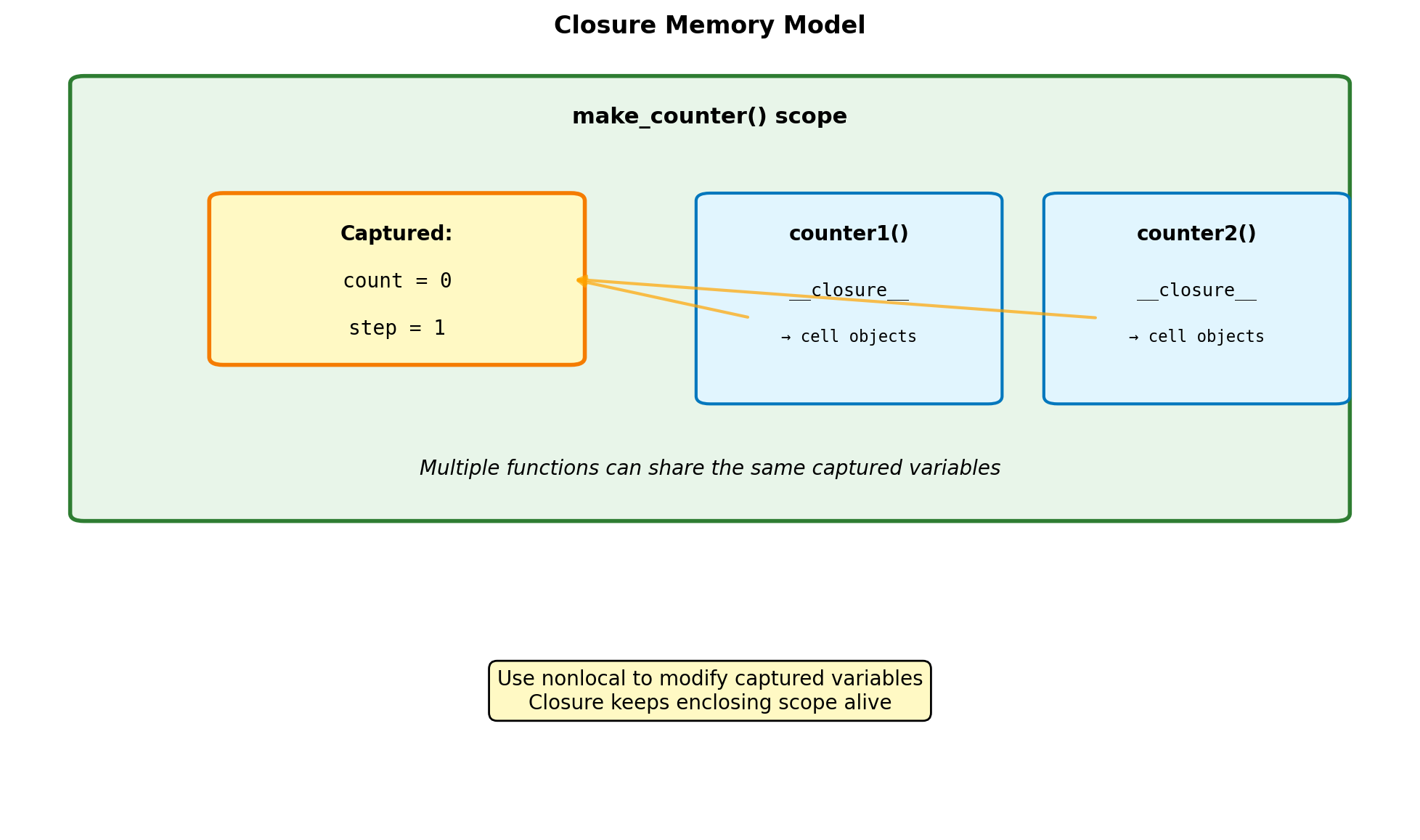

Closures and Captured State

def make_counter(initial=0):

count = initial

def increment(step=1):

nonlocal count

count += step

return count

def get_value():

return count

# Functions share the closure

increment.get = get_value

return increment

# Create closures

counter1 = make_counter()

counter2 = make_counter(100)

print("Separate closures:")

print(f" counter1(): {counter1()}")

print(f" counter1(): {counter1()}")

print(f" counter2(): {counter2()}")

# Inspect closure

import inspect

closure = inspect.getclosurevars(counter1)

print(f"\nClosure variables: {closure.nonlocals}")

# Shared state demonstration

def make_accumulator():

data = []

def add(x):

data.append(x)

return sum(data)

def reset():

data.clear()

add.reset = reset

return add

acc = make_accumulator()

print(f"\nacc(5): {acc(5)}")

print(f"acc(3): {acc(3)}")Separate closures:

counter1(): 1

counter1(): 2

counter2(): 101

Closure variables: {'count': 2}

acc(5): 5

acc(3): 8# Performance impact of closures

import timeit

# Global state

global_counter = 0

def increment_global():

global global_counter

global_counter += 1

return global_counter

# Closure state

def make_closure_counter():

counter = 0

def increment():

nonlocal counter

counter += 1

return counter

return increment

closure_inc = make_closure_counter()

# Class state

class ClassCounter:

def __init__(self):

self.counter = 0

def increment(self):

self.counter += 1

return self.counter

class_counter = ClassCounter()

# Measure

n = 100000

t_global = timeit.timeit(increment_global, number=n)

t_closure = timeit.timeit(closure_inc, number=n)

t_class = timeit.timeit(class_counter.increment, number=n)

print(f"\n{n} increments:")

print(f" Global: {t_global:.3f}s")

print(f" Closure: {t_closure:.3f}s")

print(f" Class: {t_class:.3f}s")

100000 increments:

Global: 0.003s

Closure: 0.003s

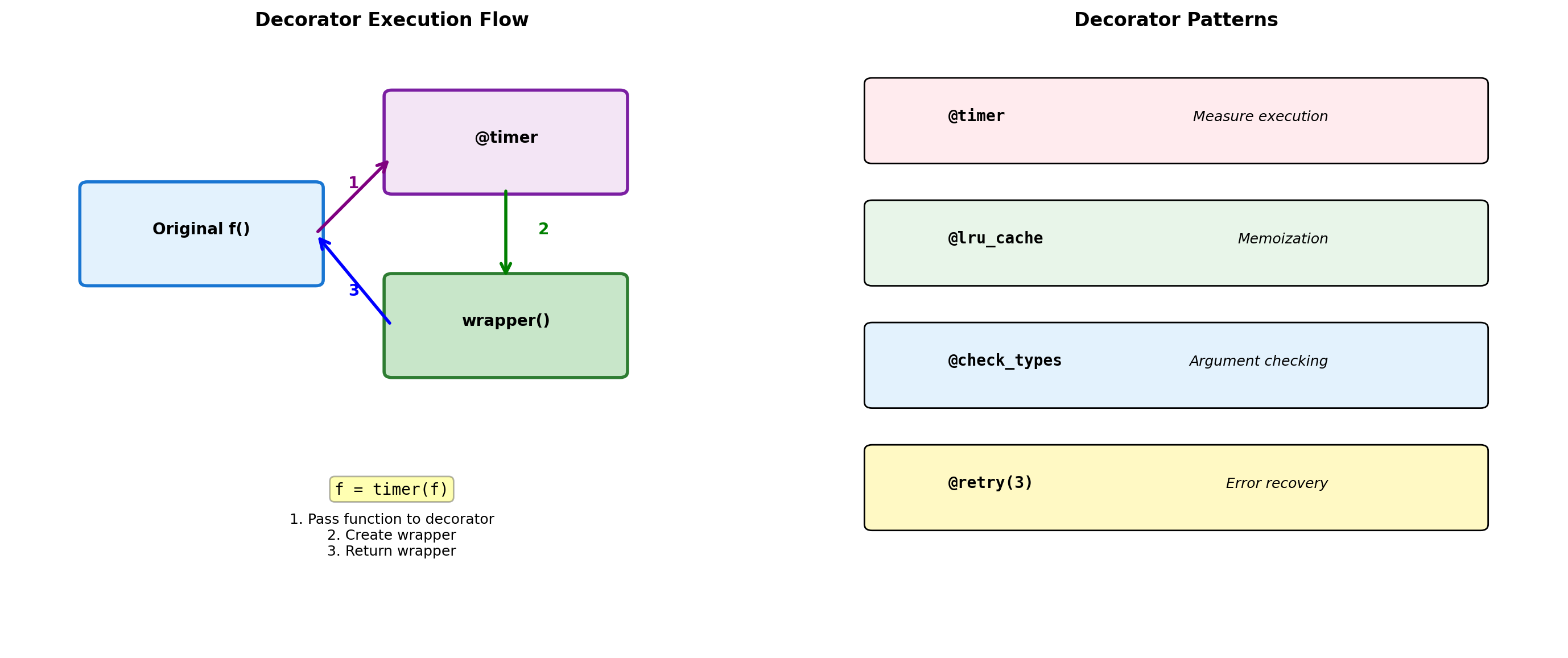

Class: 0.003sDecorators: Function Transformation

import time

import functools

def timer(func):

"""Decorator to measure execution time."""

@functools.wraps(func)

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

start = time.perf_counter()

result = func(*args, **kwargs)

elapsed = time.perf_counter() - start

print(f"{func.__name__}: {elapsed:.4f}s")

return result

return wrapper

def cache(func):

"""Simple memoization decorator."""

memo = {}

@functools.wraps(func)

def wrapper(*args):

if args in memo:

return memo[args]

result = func(*args)

memo[args] = result

return result

wrapper.cache = memo # Expose cache

return wrapper

@timer

@cache

def fibonacci(n):

if n < 2:

return n

return fibonacci(n-1) + fibonacci(n-2)

# First call builds cache

result = fibonacci(10)

print(f"fibonacci(10) = {result}")

# Check cache

print(f"Cache size: {len(fibonacci.cache)}")fibonacci: 0.0000s

fibonacci: 0.0000s

fibonacci: 0.0000s

fibonacci: 0.0000s

fibonacci: 0.0000s

fibonacci: 0.0000s

fibonacci: 0.0000s

fibonacci: 0.0000s

fibonacci: 0.0000s

fibonacci: 0.0000s

fibonacci: 0.0000s

fibonacci: 0.0000s

fibonacci: 0.0001s

fibonacci: 0.0000s

fibonacci: 0.0001s

fibonacci: 0.0000s

fibonacci: 0.0001s

fibonacci: 0.0000s

fibonacci: 0.0001s

fibonacci(10) = 55

Cache size: 11# Parameterized decorator

def validate_range(min_val, max_val):

def decorator(func):

@functools.wraps(func)

def wrapper(x):

if not min_val <= x <= max_val:

raise ValueError(f"{x} not in [{min_val}, {max_val}]")

return func(x)

return wrapper

return decorator

@validate_range(0, 1)

def probability(p):

return f"P = {p}"

print(probability(0.5))

try:

probability(1.5)

except ValueError as e:

print(f"Error: {e}")

# Stack decorators for composition

def logged(func):

@functools.wraps(func)

def wrapper(*args):

print(f"Calling {func.__name__}{args}")

return func(*args)

return wrapper

@logged

@validate_range(-1, 1)

def cosine(x):

import math

return math.cos(math.pi * x)

result = cosine(0.5)

print(f"cos(0.5π) = {result}")P = 0.5

Error: 1.5 not in [0, 1]

Calling cosine(0.5,)

cos(0.5π) = 6.123233995736766e-17Abstraction Layers in Numerical Code

import numpy as np

import timeit

# Three abstraction levels

def python_dot(a, b):

"""Pure Python dot product."""

total = 0

for i in range(len(a)):

total += a[i] * b[i]

return total

def numpy_dot(a, b):

"""NumPy dot product."""

return np.dot(a, b)

# Attempt to import numba (may not be available)

try:

from numba import jit

@jit(nopython=True)

def numba_dot(a, b):

"""JIT-compiled dot product."""

total = 0.0

for i in range(len(a)):

total += a[i] * b[i]

return total

has_numba = True

except ImportError:

has_numba = False

numba_dot = None

# Test different sizes

for size in [10, 100, 1000, 10000]:

list_a = list(range(size))

list_b = list(range(size))

arr_a = np.array(list_a, dtype=float)

arr_b = np.array(list_b, dtype=float)

t_python = timeit.timeit(

lambda: python_dot(list_a, list_b), number=100

)

t_numpy = timeit.timeit(

lambda: numpy_dot(arr_a, arr_b), number=100

)

print(f"Size {size:5d}:")

print(f" Python: {t_python*10:.3f} ms")

print(f" NumPy: {t_numpy*10:.3f} ms ({t_python/t_numpy:.0f}x)")

if has_numba and size <= 1000:

t_numba = timeit.timeit(

lambda: numba_dot(arr_a, arr_b), number=100

)

print(f" Numba: {t_numba*10:.3f} ms ({t_python/t_numba:.0f}x)")Size 10:

Python: 0.000 ms

NumPy: 0.000 ms (1x)

Size 100:

Python: 0.002 ms

NumPy: 0.001 ms (2x)

Size 1000:

Python: 0.026 ms

NumPy: 0.000 ms (55x)

Size 10000:

Python: 0.278 ms

NumPy: 0.002 ms (145x)Abstraction trade-offs:

Each layer adds overhead but provides:

- Higher-level operations

- Better maintainability

- Platform independence

- Automatic optimization

When to drop down a level:

- Inner loops with millions of iterations

- Custom algorithms not in libraries

- Memory-constrained environments

- Real-time requirements

Vectorization threshold:

- NumPy overhead ~1μs

- Break-even around 10-100 elements

- Always profile before optimizing

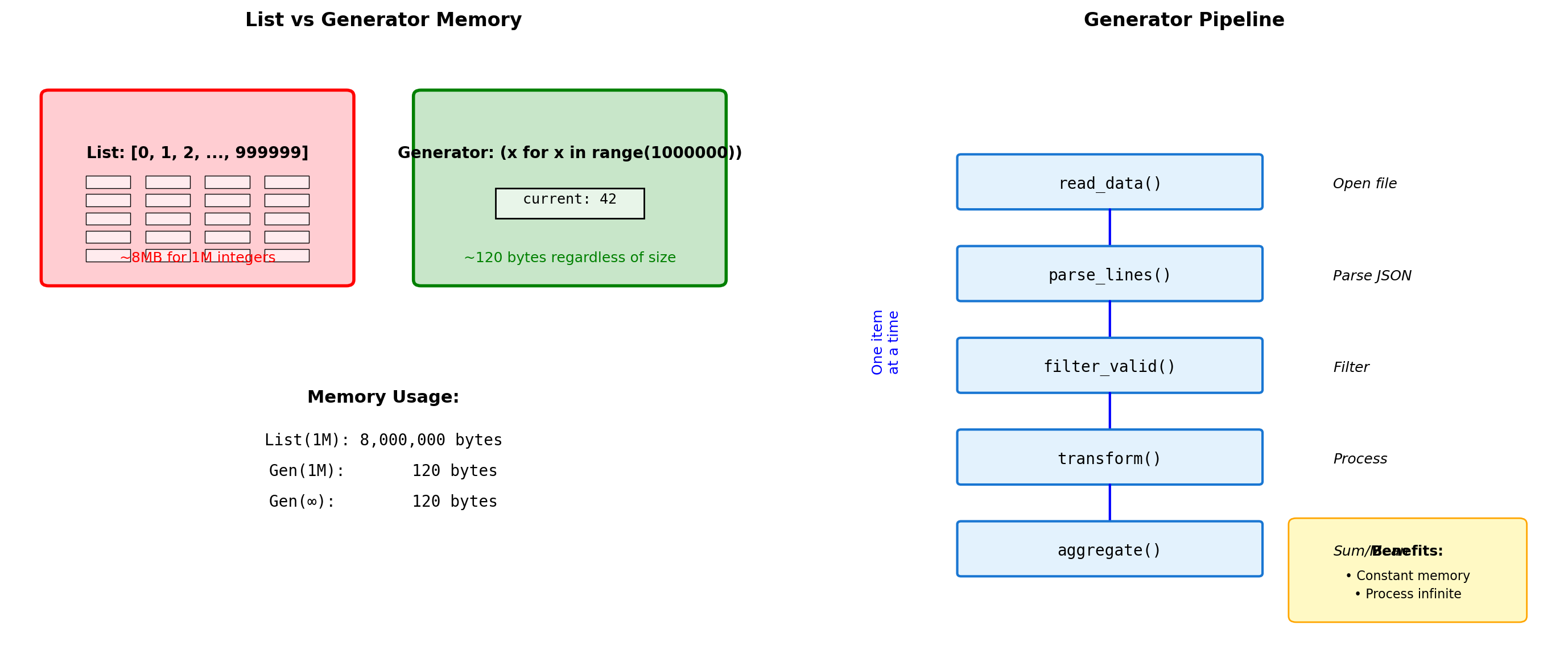

Generator Patterns for Memory Efficiency

import sys

# Memory comparison

def list_squares(n):

"""Returns list of squares."""

return [x**2 for x in range(n)]

def gen_squares(n):

"""Yields squares one at a time."""

for x in range(n):

yield x**2

# Create both

n = 1000000

squares_list = list_squares(n)

squares_gen = gen_squares(n)

print(f"Memory usage:")

print(f" List: {sys.getsizeof(squares_list):,} bytes")

print(f" Gen: {sys.getsizeof(squares_gen):,} bytes")

# Generator expressions

gen_expr = (x**2 for x in range(n))

print(f" Expr: {sys.getsizeof(gen_expr):,} bytes")

# Pipeline example

def read_numbers(filename):

"""Simulate reading numbers from file."""

for i in range(100):

yield i

def process_pipeline():

"""Chain generators for processing."""

numbers = read_numbers("data.txt")

squared = (x**2 for x in numbers)

filtered = (x for x in squared if x % 2 == 0)

result = sum(filtered) # Only here we consume

return result

result = process_pipeline()

print(f"\nPipeline result: {result}")Memory usage:

List: 8,448,728 bytes

Gen: 208 bytes

Expr: 208 bytes

Pipeline result: 161700# Infinite sequences

def fibonacci():

"""Infinite Fibonacci generator."""

a, b = 0, 1

while True:

yield a

a, b = b, a + b

# Take only what's needed

fib = fibonacci()

first_10 = [next(fib) for _ in range(10)]

print(f"First 10 Fibonacci: {first_10}")

# Generator with state

def running_average():

"""Maintains running average."""

total = 0

count = 0

while True:

value = yield total / count if count else 0

if value is not None:

total += value

count += 1

avg = running_average()

next(avg) # Prime the generator

print(f"\nRunning average:")

for val in [10, 20, 30, 40]:

result = avg.send(val)

print(f" Added {val}, average: {result:.1f}")

# Memory-efficient file processing

def process_large_file(filename):

"""Process file without loading it all."""

with open(filename, 'r') as f:

for line in f: # Generator, not list

if line.strip():

yield line.strip().upper()First 10 Fibonacci: [0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34]

Running average:

Added 10, average: 10.0

Added 20, average: 15.0

Added 30, average: 20.0

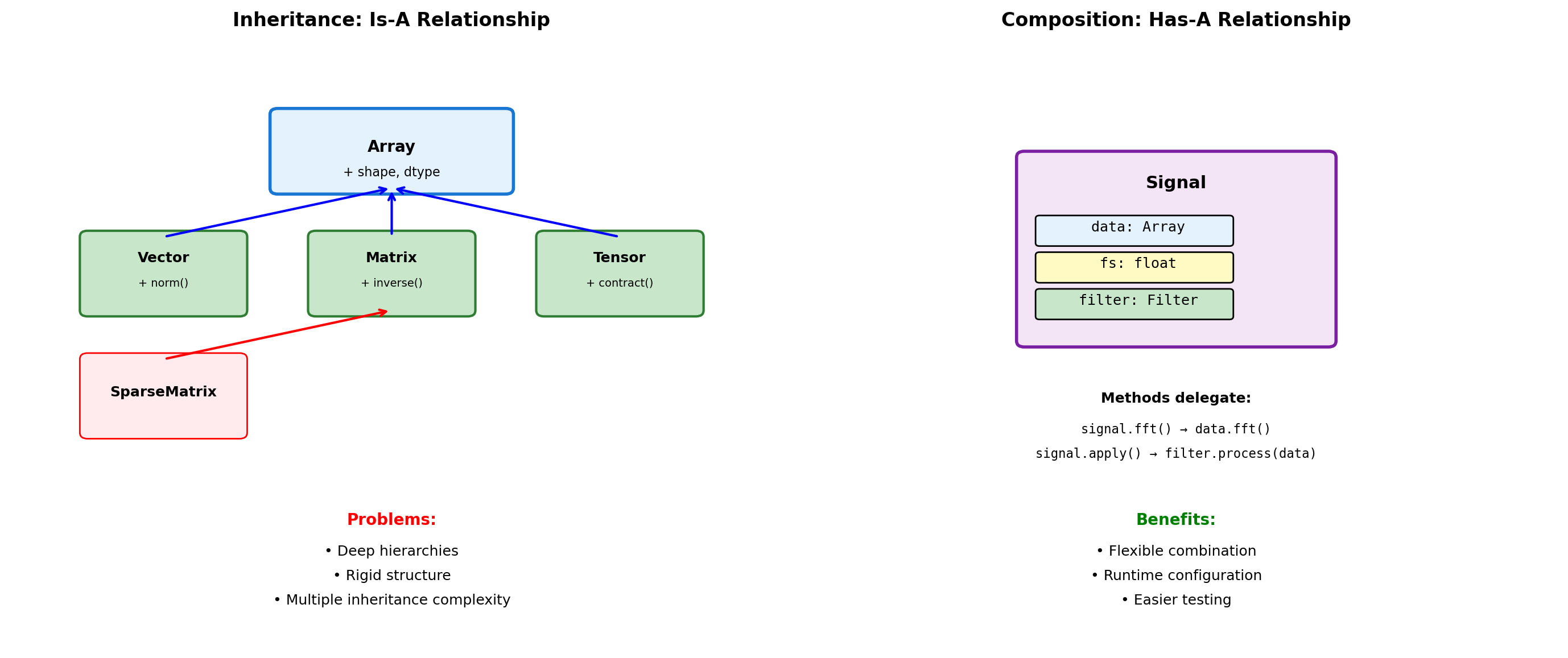

Added 40, average: 25.0Composition vs Inheritance

# Inheritance approach

class Vector(list):

"""Vector inherits from list."""

def __init__(self, components):

super().__init__(components)

def magnitude(self):

return sum(x**2 for x in self) ** 0.5

def dot(self, other):

return sum(a*b for a, b in zip(self, other))

# Problems with inheritance

v = Vector([3, 4])

print(f"Vector: {v}")

print(f"Magnitude: {v.magnitude()}")

# But inherits unwanted methods

v.reverse() # Modifies in place!

print(f"After reverse: {v}")

v.append(5) # Now 3D?

print(f"After append: {v}")Vector: [3, 4]

Magnitude: 5.0

After reverse: [4, 3]

After append: [4, 3, 5]# Composition approach

class Signal:

"""Signal uses composition."""

def __init__(self, data, sample_rate):

self._data = np.array(data)

self.fs = sample_rate

self._filter = None

def __len__(self):

return len(self._data)

def __getitem__(self, idx):

return self._data[idx]

@property

def duration(self):

return len(self._data) / self.fs

def fft(self):

"""Delegate to NumPy."""

return np.fft.fft(self._data)

def resample(self, new_rate):

"""Return new Signal."""

ratio = new_rate / self.fs

new_length = int(len(self._data) * ratio)

new_data = np.interp(

np.linspace(0, len(self._data), new_length),

np.arange(len(self._data)),

self._data

)

return Signal(new_data, new_rate)

# Clean interface

sig = Signal([1, 2, 3, 4], sample_rate=100)

print(f"Duration: {sig.duration}s")

print(f"FFT shape: {sig.fft().shape}")Duration: 0.04s

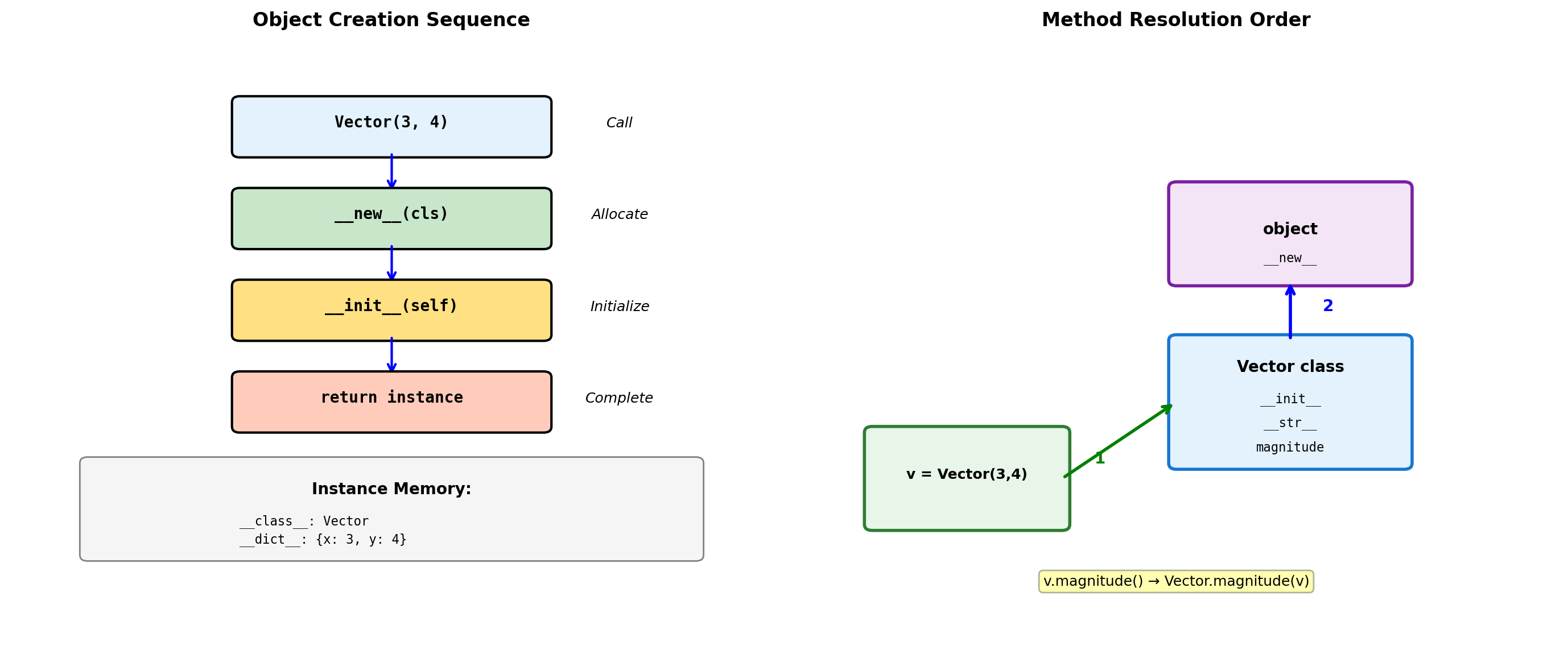

FFT shape: (4,)Classes and Operator Overloading

Object Creation and Initialization

class Vector:

"""2D vector with special methods."""

def __init__(self, x, y):

"""Initialize instance attributes."""

self.x = x

self.y = y

def __repr__(self):

"""Developer representation (for debugging)."""

return f"Vector({self.x}, {self.y})"

def __str__(self):

"""User-friendly string representation."""

return f"<{self.x}, {self.y}>"

def magnitude(self):

"""Compute vector magnitude."""

return (self.x**2 + self.y**2) ** 0.5

# Create instance

v = Vector(3, 4)

# Different string representations

print(f"repr(v): {repr(v)}")

print(f"str(v): {str(v)}")

print(f"Magnitude: {v.magnitude()}")

# Instance internals

print(f"\nInstance dict: {v.__dict__}")

print(f"Class: {v.__class__.__name__}")repr(v): Vector(3, 4)

str(v): <3, 4>

Magnitude: 5.0

Instance dict: {'x': 3, 'y': 4}

Class: Vector# Method resolution demonstration

class Base:

def method(self):

return "Base"

def override_me(self):

return "Base version"

class Derived(Base):

def override_me(self):

return "Derived version"

def method(self):

# Call parent version

parent = super().method()

return f"{parent} → Derived"

d = Derived()

print(f"d.override_me(): {d.override_me()}")

print(f"d.method(): {d.method()}")

# MRO (Method Resolution Order)

print(f"\nMRO: {[cls.__name__ for cls in Derived.__mro__]}")

# Bound vs unbound methods

print(f"\nBound method: {d.method}")

print(f"Unbound: {Derived.method}")

print(f"Same function: {d.method.__func__ is Derived.method}")d.override_me(): Derived version

d.method(): Base → Derived

MRO: ['Derived', 'Base', 'object']

Bound method: <bound method Derived.method of <__main__.Derived object at 0x32fa7f350>>

Unbound: <function Derived.method at 0x3489a3100>

Same function: TrueOperator Overloading for Numerical Types

class Vector:

def __init__(self, x, y):

self.x = x

self.y = y

def __repr__(self):

return f"Vector({self.x}, {self.y})"

# Arithmetic operators

def __add__(self, other):

if isinstance(other, Vector):

return Vector(self.x + other.x, self.y + other.y)

return NotImplemented

def __mul__(self, scalar):

if isinstance(scalar, (int, float)):

return Vector(self.x * scalar, self.y * scalar)

return NotImplemented

def __rmul__(self, scalar):

"""Right multiplication: scalar * vector"""

return self.__mul__(scalar)

def __neg__(self):

return Vector(-self.x, -self.y)

def __abs__(self):

return (self.x**2 + self.y**2) ** 0.5

# Comparison operators

def __eq__(self, other):

if not isinstance(other, Vector):

return False

return self.x == other.x and self.y == other.y

def __lt__(self, other):

"""Compare by magnitude."""

return abs(self) < abs(other)

# Usage

a = Vector(3, 4)

b = Vector(1, 2)

print(f"a = {a}")

print(f"b = {b}")

print(f"a + b = {a + b}")

print(f"2 * a = {2 * a}")

print(f"-a = {-a}")

print(f"|a| = {abs(a)}")

print(f"a == b: {a == b}")

print(f"a > b: {a > b}")a = Vector(3, 4)

b = Vector(1, 2)

a + b = Vector(4, 6)

2 * a = Vector(6, 8)

-a = Vector(-3, -4)

|a| = 5.0

a == b: False

a > b: True# In-place operators

class Matrix:

def __init__(self, data):

self.data = np.array(data, dtype=float)

def __repr__(self):

return f"Matrix({self.data.tolist()})"

def __iadd__(self, other):

"""In-place addition: m += other"""

if isinstance(other, Matrix):

self.data += other.data

elif isinstance(other, (int, float)):

self.data += other

else:

return NotImplemented

return self # Must return self

def __matmul__(self, other):

"""Matrix multiplication: m @ other"""

if isinstance(other, Matrix):

return Matrix(self.data @ other.data)

return NotImplemented

def __getitem__(self, key):

"""Indexing: m[i, j]"""

return self.data[key]

def __setitem__(self, key, value):

"""Assignment: m[i, j] = value"""

self.data[key] = value

# Usage

m1 = Matrix([[1, 2], [3, 4]])

m2 = Matrix([[5, 6], [7, 8]])

print(f"m1 = {m1}")

print(f"m2 = {m2}")

print(f"m1 @ m2 = {m1 @ m2}")

print(f"m1[0, 1] = {m1[0, 1]}")

m1 += 10

print(f"After m1 += 10: {m1}")m1 = Matrix([[1.0, 2.0], [3.0, 4.0]])

m2 = Matrix([[5.0, 6.0], [7.0, 8.0]])

m1 @ m2 = Matrix([[19.0, 22.0], [43.0, 50.0]])

m1[0, 1] = 2.0

After m1 += 10: Matrix([[11.0, 12.0], [13.0, 14.0]])Properties and Descriptors

class Temperature:

"""Temperature with Celsius/Fahrenheit properties."""

def __init__(self, celsius=0):

self._celsius = celsius

@property

def celsius(self):

"""Getter for Celsius."""

return self._celsius

@celsius.setter

def celsius(self, value):

"""Setter with validation."""

if value < -273.15:

raise ValueError(f"Temperature below absolute zero")

self._celsius = value

@property

def fahrenheit(self):

"""Computed Fahrenheit property."""

return self._celsius * 9/5 + 32

@fahrenheit.setter

def fahrenheit(self, value):

"""Set via Fahrenheit."""

self.celsius = (value - 32) * 5/9

@property

def kelvin(self):

"""Read-only Kelvin property."""

return self._celsius + 273.15

# Usage

temp = Temperature(25)

print(f"Celsius: {temp.celsius}°C")

print(f"Fahrenheit: {temp.fahrenheit}°F")

print(f"Kelvin: {temp.kelvin}K")

temp.fahrenheit = 86

print(f"\nAfter setting 86°F:")

print(f"Celsius: {temp.celsius}°C")

try:

temp.celsius = -300

except ValueError as e:

print(f"\nValidation error: {e}")Celsius: 25°C

Fahrenheit: 77.0°F

Kelvin: 298.15K

After setting 86°F:

Celsius: 30.0°C

Validation error: Temperature below absolute zeroWhen to use properties:

- Computed values derived from other attributes

- Validation on attribute assignment

- Converting between representations (e.g., Celsius/Fahrenheit)

- Read-only attributes that shouldn’t be modified

Property mechanics:

- Getter: Called on

obj.attraccess - Setter: Called on

obj.attr = valueassignment - Deleter: Called on

del obj.attr - Properties are descriptors under the hood

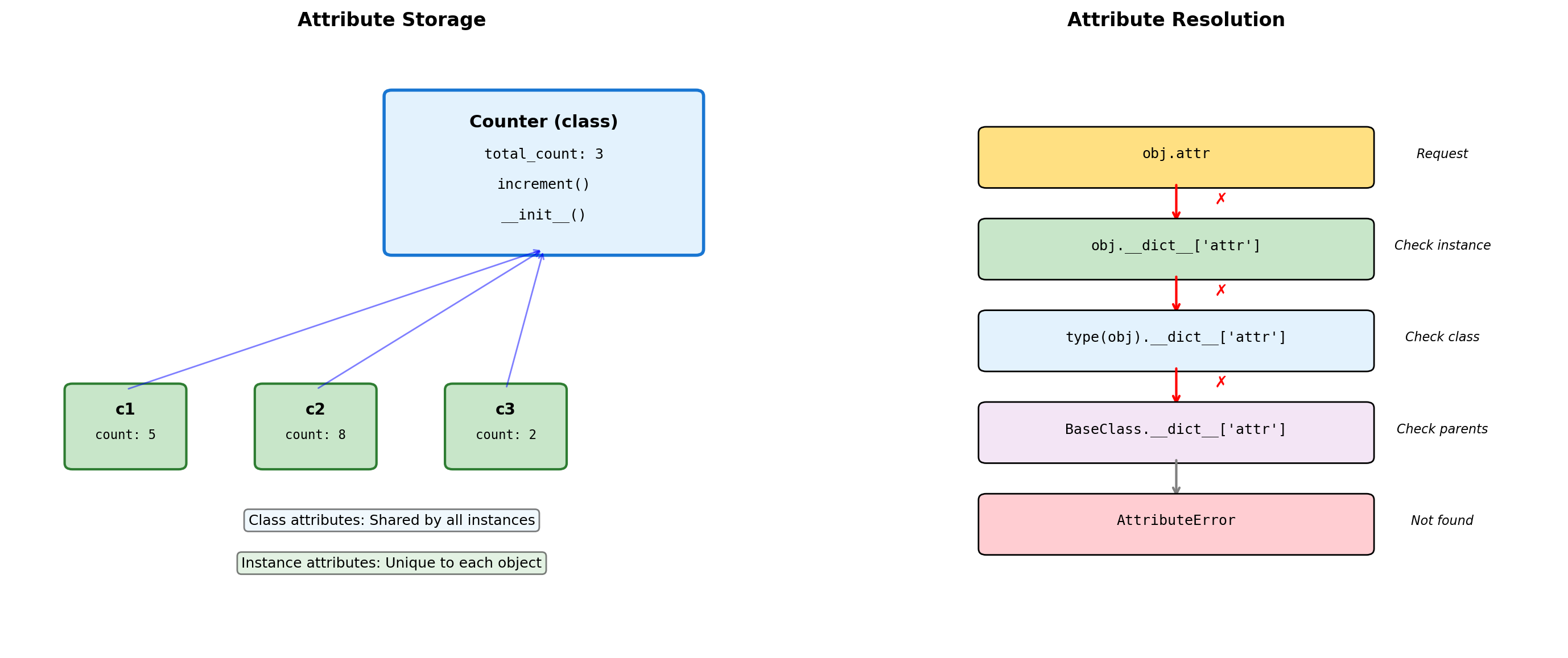

Class vs Instance Attributes

class Counter:

"""Demonstrates class vs instance attributes."""

# Class attribute (shared)

total_instances = 0

default_step = 1

def __init__(self, initial=0):

# Instance attributes (unique)

self.count = initial

Counter.total_instances += 1

def increment(self, step=None):

# Use class default if not specified

if step is None:

step = self.default_step

self.count += step

@classmethod

def get_total(cls):

"""Class method accesses class attributes."""

return cls.total_instances

@staticmethod

def validate_step(step):

"""Static method - no access to instance or class."""

return step > 0

# Create instances

c1 = Counter()

c2 = Counter(10)

c3 = Counter(20)

print(f"Total instances: {Counter.total_instances}")

print(f"c1.count: {c1.count}")

print(f"c2.count: {c2.count}")

# Modify class attribute

Counter.default_step = 5

c1.increment()

c2.increment()

print(f"\nAfter increment with step=5:")

print(f"c1.count: {c1.count}")

print(f"c2.count: {c2.count}")

# Instance shadows class attribute

c1.default_step = 10

print(f"\nc1.default_step: {c1.default_step}")

print(f"c2.default_step: {c2.default_step}")Total instances: 3

c1.count: 0

c2.count: 10

After increment with step=5:

c1.count: 5

c2.count: 15

c1.default_step: 10

c2.default_step: 5Class vs instance attributes:

- Class attributes: Shared by all instances, defined at class level

- Instance attributes: Unique to each object, defined in

__init__ - Instance attributes shadow class attributes of the same name

Method types:

- Instance methods:

selfas first argument, access instance state - Class methods (

@classmethod):clsas first argument, access class state - Static methods (

@staticmethod): No implicit argument, utility functions

Common patterns:

- Class-level defaults modified per-instance

- Instance counters via class attributes

- Factory methods via

@classmethod

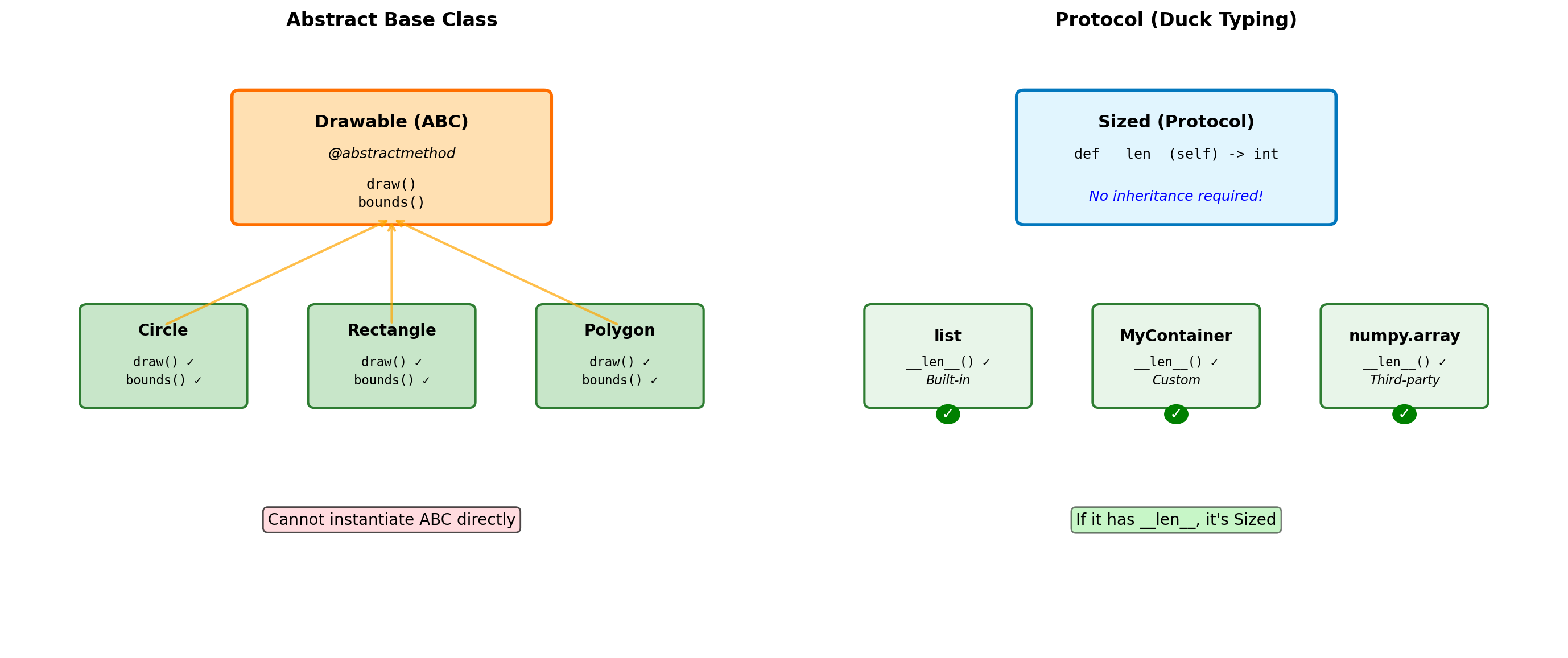

Abstract Base Classes and Protocols

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

import math

class Shape(ABC):

"""Abstract base class for shapes."""

@abstractmethod

def area(self):

"""Must be implemented by subclasses."""

pass

@abstractmethod

def perimeter(self):

"""Must be implemented by subclasses."""

pass

def describe(self):

"""Concrete method using abstract methods."""

return f"Area: {self.area():.2f}, Perimeter: {self.perimeter():.2f}"

class Circle(Shape):

def __init__(self, radius):

self.radius = radius

def area(self):

return math.pi * self.radius ** 2

def perimeter(self):

return 2 * math.pi * self.radius

class Rectangle(Shape):

def __init__(self, width, height):

self.width = width

self.height = height

def area(self):

return self.width * self.height

def perimeter(self):

return 2 * (self.width + self.height)

# Cannot instantiate ABC

try:

shape = Shape() # Error!

except TypeError as e:

print(f"Error: {e}")

# Concrete classes work

circle = Circle(5)

rect = Rectangle(3, 4)

print(f"\nCircle: {circle.describe()}")

print(f"Rectangle: {rect.describe()}")

# Check inheritance

print(f"\nisinstance(circle, Shape): {isinstance(circle, Shape)}")Error: Can't instantiate abstract class Shape with abstract methods area, perimeter

Circle: Area: 78.54, Perimeter: 31.42

Rectangle: Area: 12.00, Perimeter: 14.00

isinstance(circle, Shape): TrueWhen to use ABCs:

- Defining interfaces that must be implemented

- Template Method pattern (concrete methods calling abstract ones)

- Enforcing contracts in a class hierarchy

- When you want

isinstance()checks against the interface

ABC vs Duck Typing:

- ABCs: Explicit contracts, errors at instantiation time

- Duck typing: Implicit contracts, errors at call time

- Python prefers duck typing, but ABCs useful for frameworks

Built-in ABCs (collections.abc):

Iterable,Iterator,SequenceMapping,MutableMappingCallable,Hashable

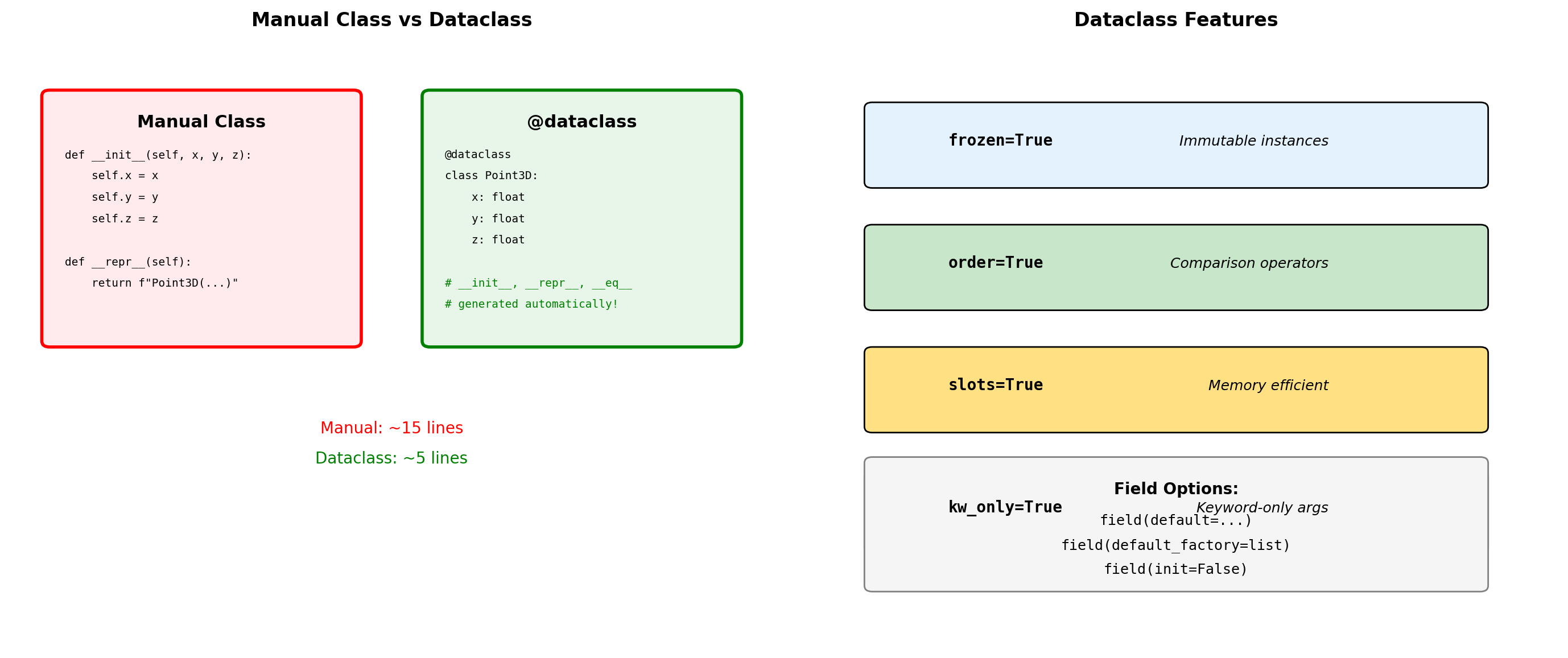

Dataclasses for Numerical Structures

from dataclasses import dataclass, field

from typing import List

import numpy as np

@dataclass

class DataPoint:

"""Simple data container."""

x: float

y: float

label: str = "unlabeled"

metadata: dict = field(default_factory=dict)

def distance_to(self, other):

"""Euclidean distance."""

return ((self.x - other.x)**2 +

(self.y - other.y)**2) ** 0.5

@dataclass(frozen=True)

class ImmutableVector:

"""Frozen dataclass - hashable."""

x: float

y: float

z: float

def magnitude(self):

return (self.x**2 + self.y**2 + self.z**2) ** 0.5

def __add__(self, other):

"""Return new vector (immutable)."""

return ImmutableVector(

self.x + other.x,

self.y + other.y,

self.z + other.z

)

# Usage

p1 = DataPoint(3, 4)

p2 = DataPoint(6, 8, "target")

print(f"p1: {p1}")

print(f"p2: {p2}")

print(f"Distance: {p1.distance_to(p2):.2f}")

# Frozen vector

v1 = ImmutableVector(1, 2, 3)

v2 = ImmutableVector(4, 5, 6)

v3 = v1 + v2

print(f"\nv1 + v2 = {v3}")

print(f"Hashable: {hash(v1)}")

# Can use as dict key

vector_dict = {v1: "first", v2: "second"}p1: DataPoint(x=3, y=4, label='unlabeled', metadata={})

p2: DataPoint(x=6, y=8, label='target', metadata={})

Distance: 5.00

v1 + v2 = ImmutableVector(x=5, y=7, z=9)

Hashable: 529344067295497451@dataclass(order=True)

class Measurement:

"""Sortable measurement with validation."""

timestamp: float = field(compare=True)

value: float = field(compare=False)

sensor_id: str = field(default="unknown", compare=False)

def __post_init__(self):

"""Validation after initialization."""

if self.value < 0:

raise ValueError(f"Negative value: {self.value}")

if self.timestamp < 0:

raise ValueError(f"Invalid timestamp: {self.timestamp}")

# Sorting by timestamp

measurements = [

Measurement(100.5, 23.4, "A1"),

Measurement(99.2, 25.1, "A2"),

Measurement(101.3, 22.8, "A1"),

]

sorted_measurements = sorted(measurements)

print("Sorted by timestamp:")

for m in sorted_measurements:

print(f" t={m.timestamp}: {m.value}")

# Performance comparison

from dataclasses import dataclass

import sys

@dataclass(slots=True)

class SlottedPoint:

x: float

y: float

@dataclass

class RegularPoint:

x: float

y: float

sp = SlottedPoint(1, 2)

rp = RegularPoint(1, 2)

print(f"\nMemory usage:")

print(f" With slots: {sys.getsizeof(sp)} bytes")

print(f" Regular: {sys.getsizeof(rp) + sys.getsizeof(rp.__dict__)} bytes")Sorted by timestamp:

t=99.2: 25.1

t=100.5: 23.4

t=101.3: 22.8

Memory usage:

With slots: 48 bytes

Regular: 352 bytesNumPy Arrays

Why NumPy Exists: Python’s Performance Wall

NumPy solves Python’s fundamental limitation: every operation triggers expensive interpreter overhead.

import numpy as np

import timeit

# Demonstrate the performance difference

def python_add(list1, list2):

"""Pure Python element-wise addition."""

result = []

for i in range(len(list1)):

result.append(list1[i] + list2[i])

return result

def numpy_add(arr1, arr2):

"""NumPy vectorized addition."""

return arr1 + arr2

# Test data

size = 100000

py_list1 = list(range(size))

py_list2 = list(range(size, size*2))

np_arr1 = np.array(py_list1)

np_arr2 = np.array(py_list2)

# Benchmark

t_python = timeit.timeit(

lambda: python_add(py_list1, py_list2),

number=10

)

t_numpy = timeit.timeit(

lambda: numpy_add(np_arr1, np_arr2),

number=10

)

print(f"Adding {size:,} numbers (10 iterations):")

print(f" Python lists: {t_python:.3f}s")

print(f" NumPy arrays: {t_numpy:.3f}s")

print(f" Speedup: {t_python/t_numpy:.0f}x")

# Show function call overhead

python_ops = size * 4 # loop, 2 indexes, 1 addition per iteration

numpy_ops = 1 # single function call

print(f"\nPython operations: {python_ops:,}")

print(f"NumPy operations: {numpy_ops}")

print(f"Overhead reduction: {python_ops/numpy_ops:.0f}x")Adding 100,000 numbers (10 iterations):

Python lists: 0.024s

NumPy arrays: 0.000s

Speedup: 61x

Python operations: 400,000

NumPy operations: 1

Overhead reduction: 400000xThe NumPy Solution:

- Homogeneous data - All elements same type, enabling compact storage

- Contiguous memory - Cache-friendly access patterns

- Vectorized operations - Single Python call processes entire arrays

- C implementation - Inner loops run at machine speed

Cost of flexibility:

- Python lists can mix types, NumPy arrays cannot

- Dynamic resizing is expensive in NumPy

- Small arrays may be slower due to overhead

When NumPy wins:

- Numerical computations on large datasets

- Element-wise operations

- Mathematical functions (sin, cos, exp)

- Linear algebra operations

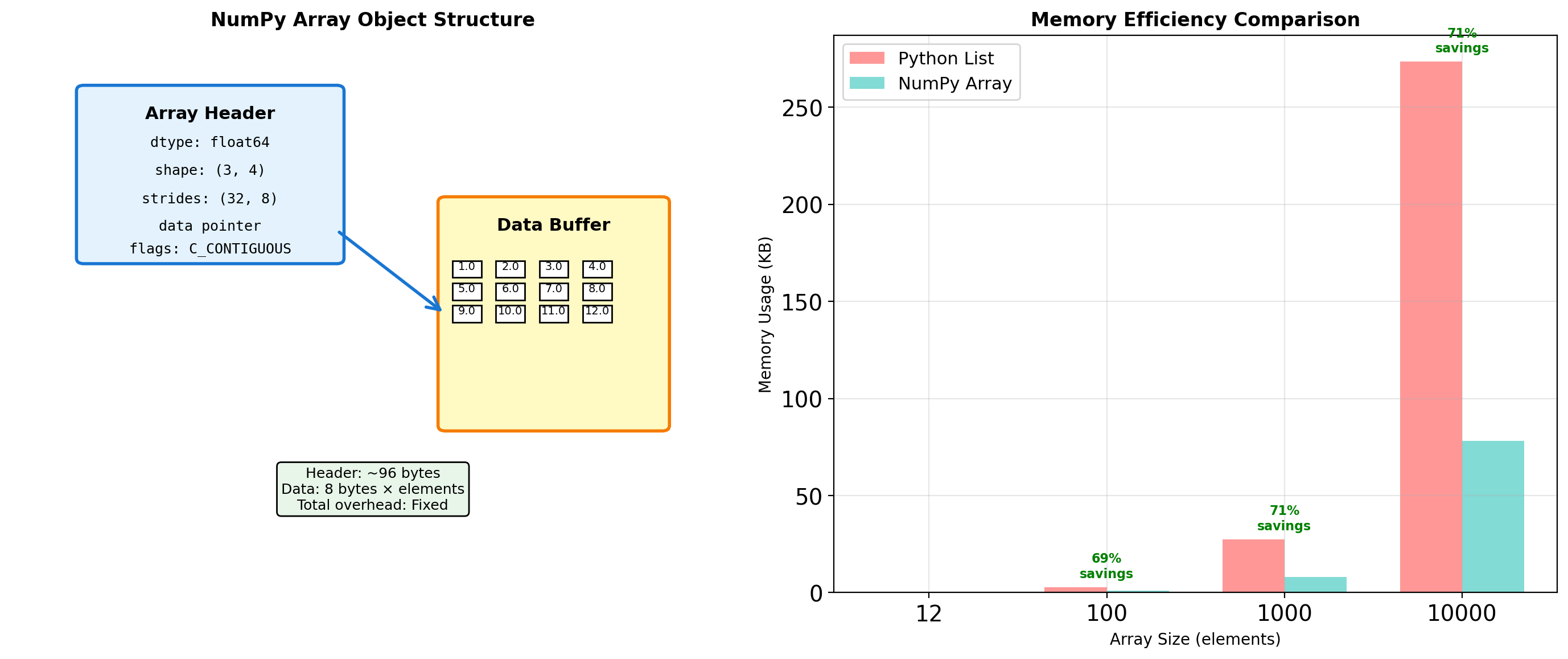

Array Object Internals: More Than Just Data

NumPy arrays are sophisticated objects that separate metadata from data, enabling powerful features like views and broadcasting.

import numpy as np

import sys

# Examine array internals

arr = np.arange(12, dtype=np.float64).reshape(3, 4)

print("Array structure analysis:")

print(f" Array object size: {sys.getsizeof(arr)} bytes")

print(f" Data buffer size: {arr.nbytes} bytes")

print(f" Shape: {arr.shape}")

print(f" Strides: {arr.strides}") # Bytes to next element in each dimension

print(f" Data type: {arr.dtype}")

print(f" Item size: {arr.itemsize} bytes")

# Memory layout inspection

print(f"\nMemory layout:")

print(f" C-contiguous: {arr.flags['C_CONTIGUOUS']}")

print(f" F-contiguous: {arr.flags['F_CONTIGUOUS']}")

print(f" Owns data: {arr.flags['OWNDATA']}")

# Compare with Python list

py_list = arr.tolist()

print(f"\nMemory comparison for 12 elements:")

print(f" NumPy array: {sys.getsizeof(arr) + arr.nbytes} bytes total")

print(f" Python list: {sys.getsizeof(py_list)} bytes (list)")

# Calculate Python list element overhead

element_overhead = sum(sys.getsizeof(x) for row in py_list for x in row)

print(f" Python objects: {element_overhead} bytes (elements)")

print(f" Python total: {sys.getsizeof(py_list) + element_overhead} bytes")

# Show memory addressing

print(f"\nMemory addressing:")

print(f" Base address: {arr.__array_interface__['data'][0]:#x}")

print(f" Element [0,0] offset: 0 bytes")

print(f" Element [0,1] offset: {arr.strides[1]} bytes")

print(f" Element [1,0] offset: {arr.strides[0]} bytes")

# Demonstrate stride calculation

row, col = 1, 2

offset = row * arr.strides[0] + col * arr.strides[1]

print(f" Element [1,2] offset: {offset} bytes → value {arr[1,2]}")Array structure analysis:

Array object size: 128 bytes

Data buffer size: 96 bytes

Shape: (3, 4)

Strides: (32, 8)

Data type: float64

Item size: 8 bytes

Memory layout:

C-contiguous: True

F-contiguous: False

Owns data: False

Memory comparison for 12 elements:

NumPy array: 224 bytes total

Python list: 80 bytes (list)

Python objects: 288 bytes (elements)

Python total: 368 bytes

Memory addressing:

Base address: 0x1225bbe60

Element [0,0] offset: 0 bytes

Element [0,1] offset: 8 bytes

Element [1,0] offset: 32 bytes

Element [1,2] offset: 48 bytes → value 6.0Array metadata enables:

- Reshaping without copying - Same data, different view

- Slicing creates views - No memory duplication

- Broadcasting - Operations on different-shaped arrays

- Memory mapping - Work with files larger than RAM

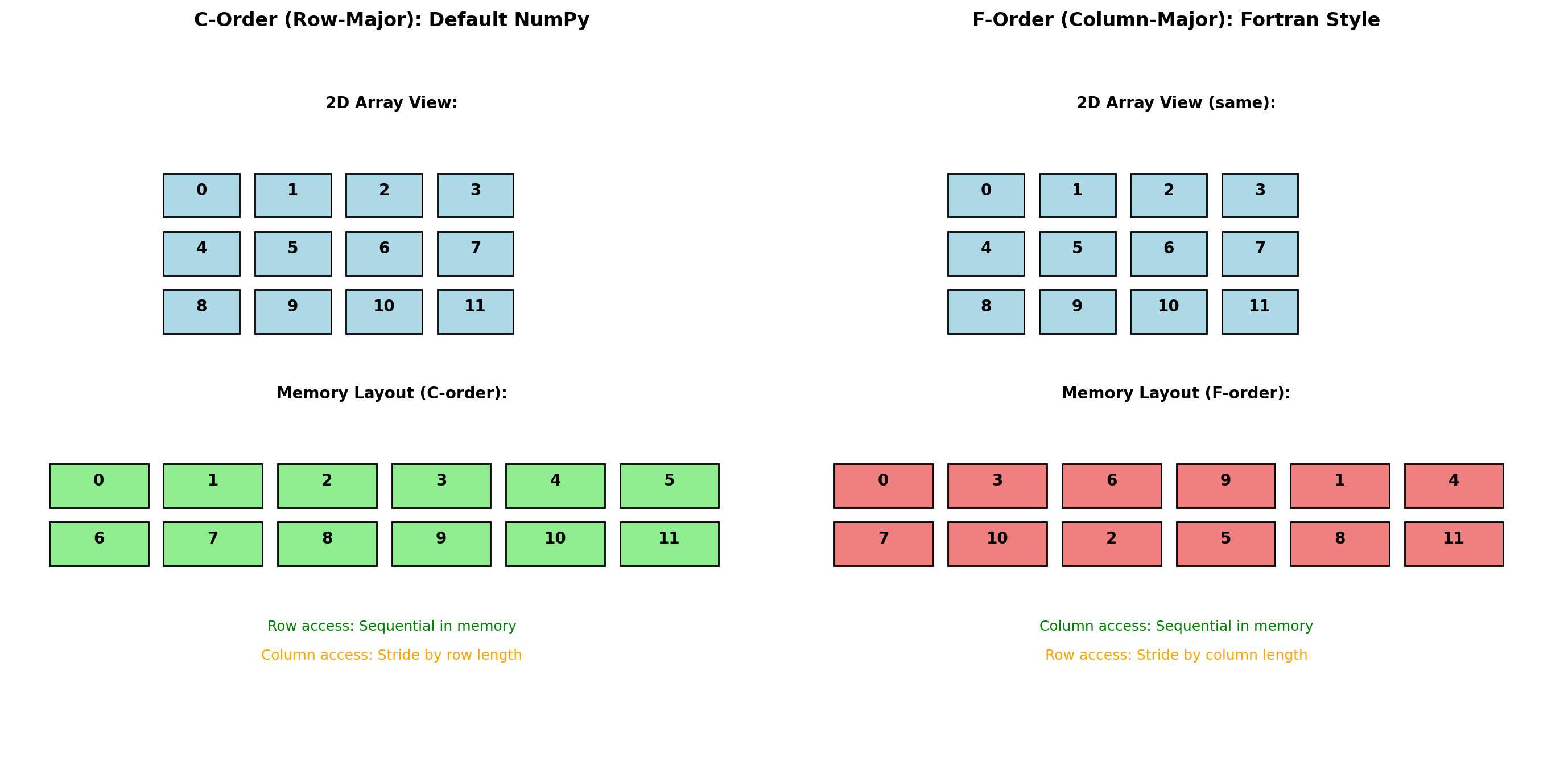

Memory Layout: Row-Major vs Column-Major

Array element ordering in memory affects performance significantly due to CPU cache behavior.

import numpy as np

import timeit

# Create arrays with different memory layouts

size = 1000

c_array = np.random.rand(size, size) # C-order (default)

f_array = np.asfortranarray(c_array) # F-order copy

print("Memory layout comparison:")

print(f"C-order shape: {c_array.shape}, strides: {c_array.strides}")

print(f"F-order shape: {f_array.shape}, strides: {f_array.strides}")

print(f"C-order flags: C={c_array.flags.c_contiguous}, F={c_array.flags.f_contiguous}")

print(f"F-order flags: C={f_array.flags.c_contiguous}, F={f_array.flags.f_contiguous}")

# Row access performance (C-order wins)

def sum_rows(arr):

return [np.sum(arr[i, :]) for i in range(100)]

# Column access performance (F-order wins)

def sum_cols(arr):

return [np.sum(arr[:, j]) for j in range(100)]

t_c_rows = timeit.timeit(lambda: sum_rows(c_array), number=100)

t_f_rows = timeit.timeit(lambda: sum_rows(f_array), number=100)

t_c_cols = timeit.timeit(lambda: sum_cols(c_array), number=100)

t_f_cols = timeit.timeit(lambda: sum_cols(f_array), number=100)

print(f"\nRow access performance (100 iterations):")

print(f" C-order: {t_c_rows:.3f}s")

print(f" F-order: {t_f_rows:.3f}s ({t_f_rows/t_c_rows:.1f}x slower)")

print(f"\nColumn access performance (100 iterations):")

print(f" C-order: {t_c_cols:.3f}s")

print(f" F-order: {t_f_cols:.3f}s ({t_c_cols/t_f_cols:.1f}x faster)")Memory layout comparison:

C-order shape: (1000, 1000), strides: (8000, 8)