MMSE Estimation and Prediction

EE 541 - Unit 3

Spring 2026

Outline

Estimation Theory

- Loss functions and MSE

- Predictor classes

- Computing \(\mathbb{E}[Y|X]\)

- Total expectation

- Var(Y|X) as irreducible uncertainty

- \(\mathbb{E}[Y|X]\) minimizes MSE

- MSE\(_{\min}\) = \(\mathbb{E}[\text{Var}(Y|X)]\)

Linear Methods

- Optimal slope: \(\text{Cov}(X,Y)/\text{Var}(X)\)

- Orthogonality principle

- \(\rho^2\) = variance explained

- LMMSE = MMSE for Gaussian

- Normal equations

- KL transform and decorrelation

Estimation Under Partial Observability

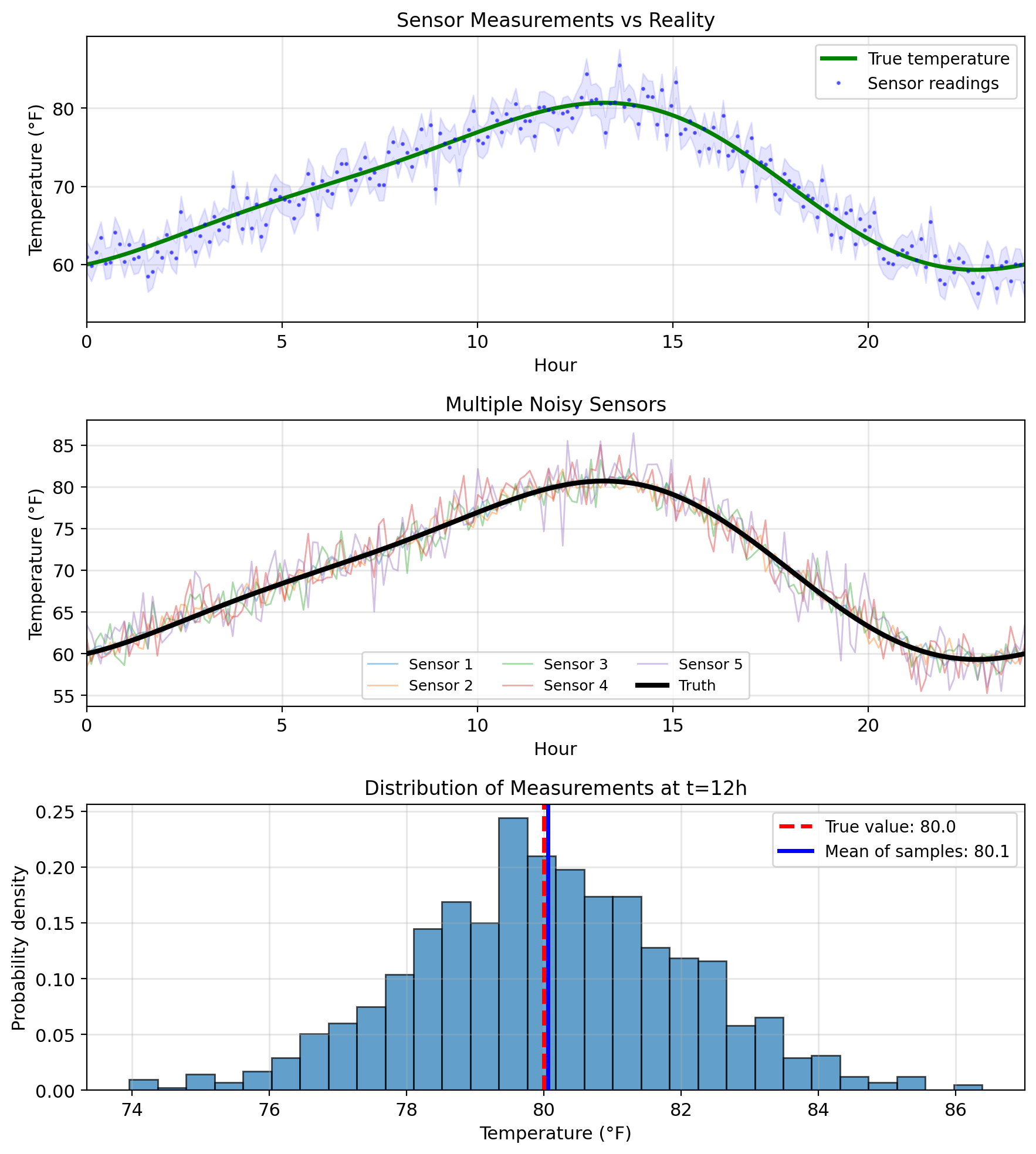

Sensors Measure with Noise

Partial observability is fundamental

Real systems operate with incomplete information:

- Temperature sensor reads 72°F ± 2°F

- Radar measures distance with noise

- Stock price reflects unknown future earnings

- MRI image contains artifacts

Objective: Given measurements (\(X\)), infer unknowns (\(Y\))

Uncertainty is inherent, not a nuisance

- Measurement noise

- Model uncertainty

- Finite samples

- Quantization effects

Need algorithms for optimal inference under uncertainty

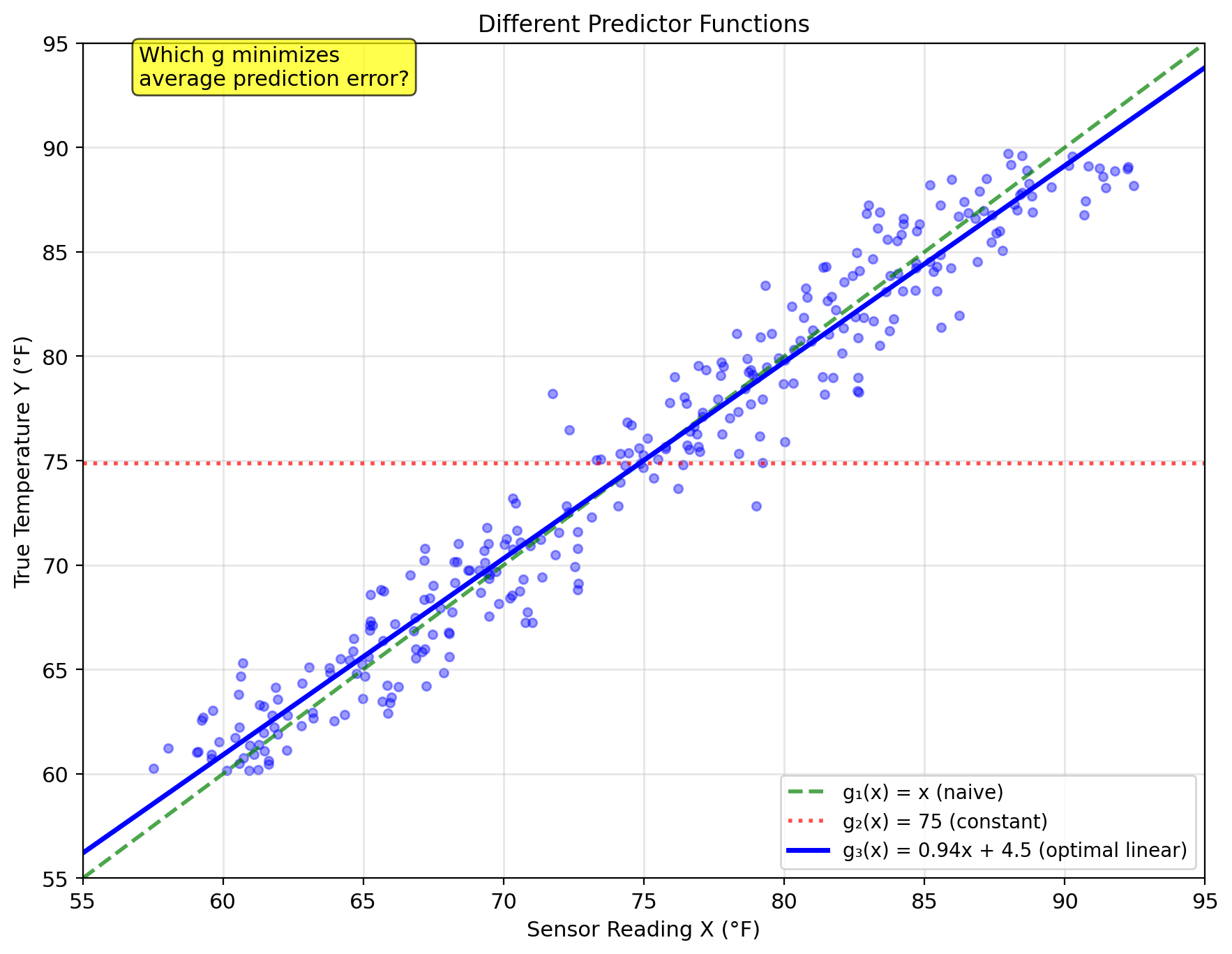

Best Predictor Minimizes Expected Loss

Problem:

- \(Y\): quantity of interest (unknown)

- \(X\): observation (known)

- \((X, Y)\): jointly distributed random variables

Predictor function: \(g: \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\) \[\hat{Y} = g(X)\]

Example: Room temperature estimation

- \(Y\): true temperature

- \(X\): sensor reading = \(Y + N\)

- \(N\): measurement noise

- \(g(X) =\) ? Best guess for \(Y\) given reading \(X\)

Among all possible functions \(g\), which one is “best”?

Need:

- What we mean by “best” (loss function)

- How to average over randomness (expectation)

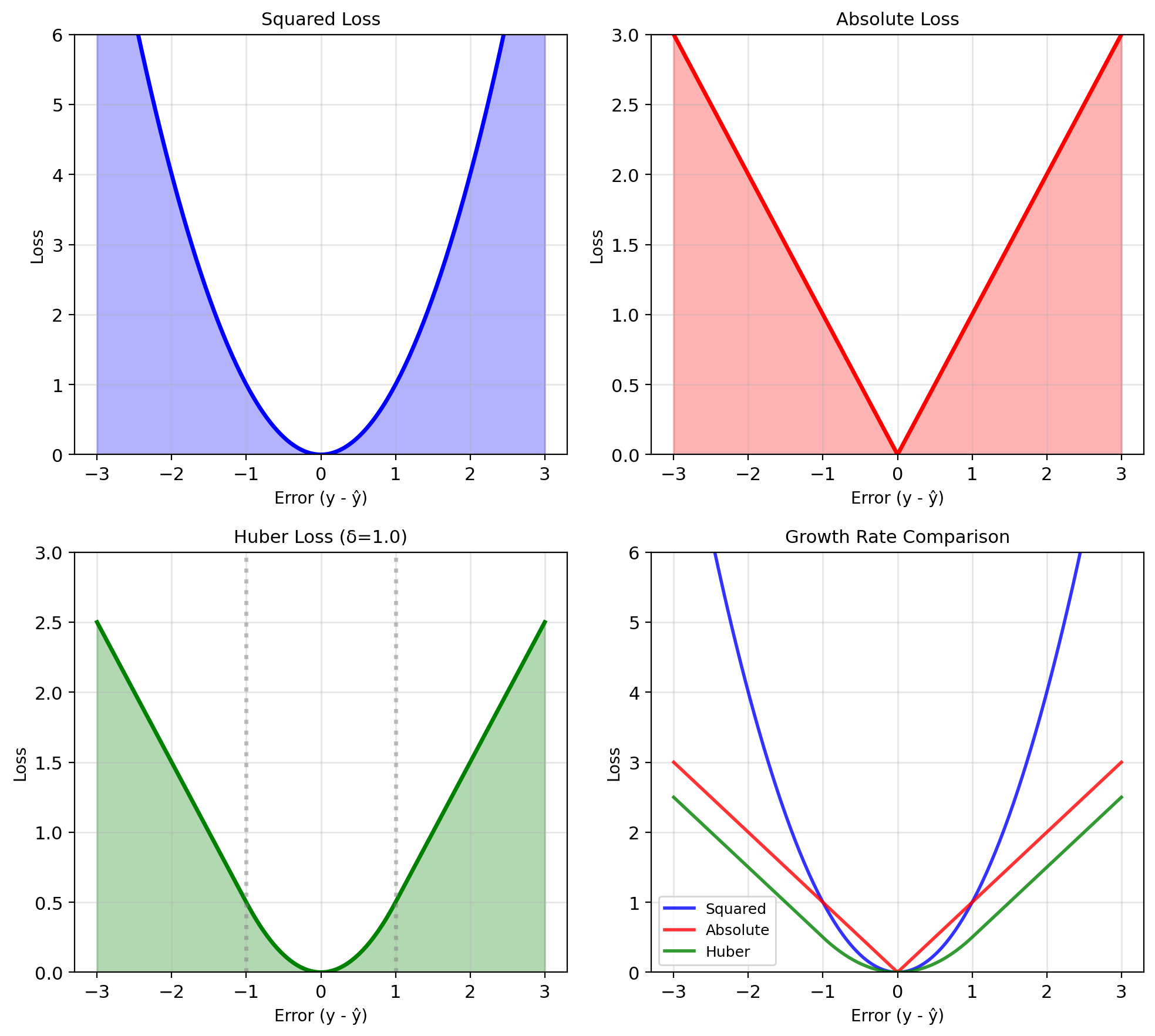

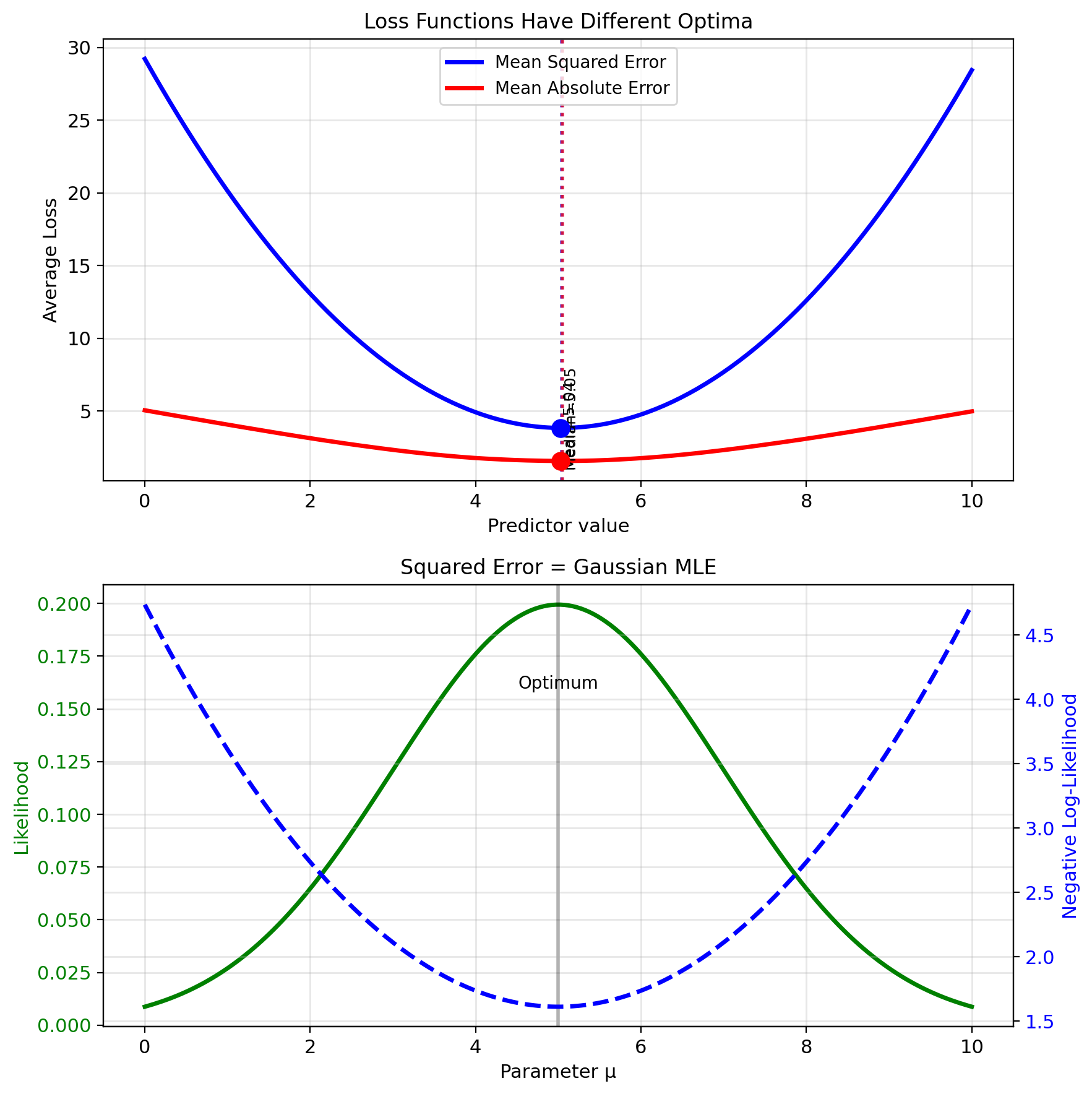

Loss Functions Penalize Prediction Error

Loss function \(\ell(y, \hat{y})\) measures prediction quality

Common choices:

| Loss | Formula | Properties |

|---|---|---|

| Squared | \((y - \hat{y})^2\) | Differentiable, convex, emphasizes large errors |

| Absolute | \(\|y - \hat{y}\|\) | Robust to outliers, non-differentiable at 0 |

| 0-1 | \(\mathbb{1}[y \neq \hat{y}]\) | Classification, discontinuous |

| Huber | \(\begin{cases} \frac{1}{2}(y-\hat{y})^2 & \|y-\hat{y}\| \leq \delta \\ \delta\|y-\hat{y}\| - \frac{\delta^2}{2} & \text{otherwise} \end{cases}\) | Robust + differentiable |

Risk: Expected loss over joint distribution \[R(g) = \mathbb{E}[\ell(Y, g(X))] = \int\int \ell(y, g(x)) p(x,y) \, dx \, dy\]

Goal: Find \(g^* = \arg\min_g R(g)\)

Squared Error Gives Closed Forms

Mathematical advantages:

Differentiable: \[\frac{d}{d\hat{y}}(y - \hat{y})^2 = -2(y - \hat{y})\] Smooth objective

Unique minimum: Strictly convex → no local minima

Closed-form solutions: Often analytically tractable

Decomposition: \[\text{MSE} = \text{Bias}^2 + \text{Variance}\]

Statistical connection:

Under Gaussian noise \(N \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma^2)\): \[Y = \mu + N\]

Maximum likelihood estimation: \[\hat{\mu}_{\text{MLE}} = \arg\max_\mu p(y|\mu) = \arg\min_\mu (y - \mu)^2\]

MSE ↔︎ Gaussian MLE

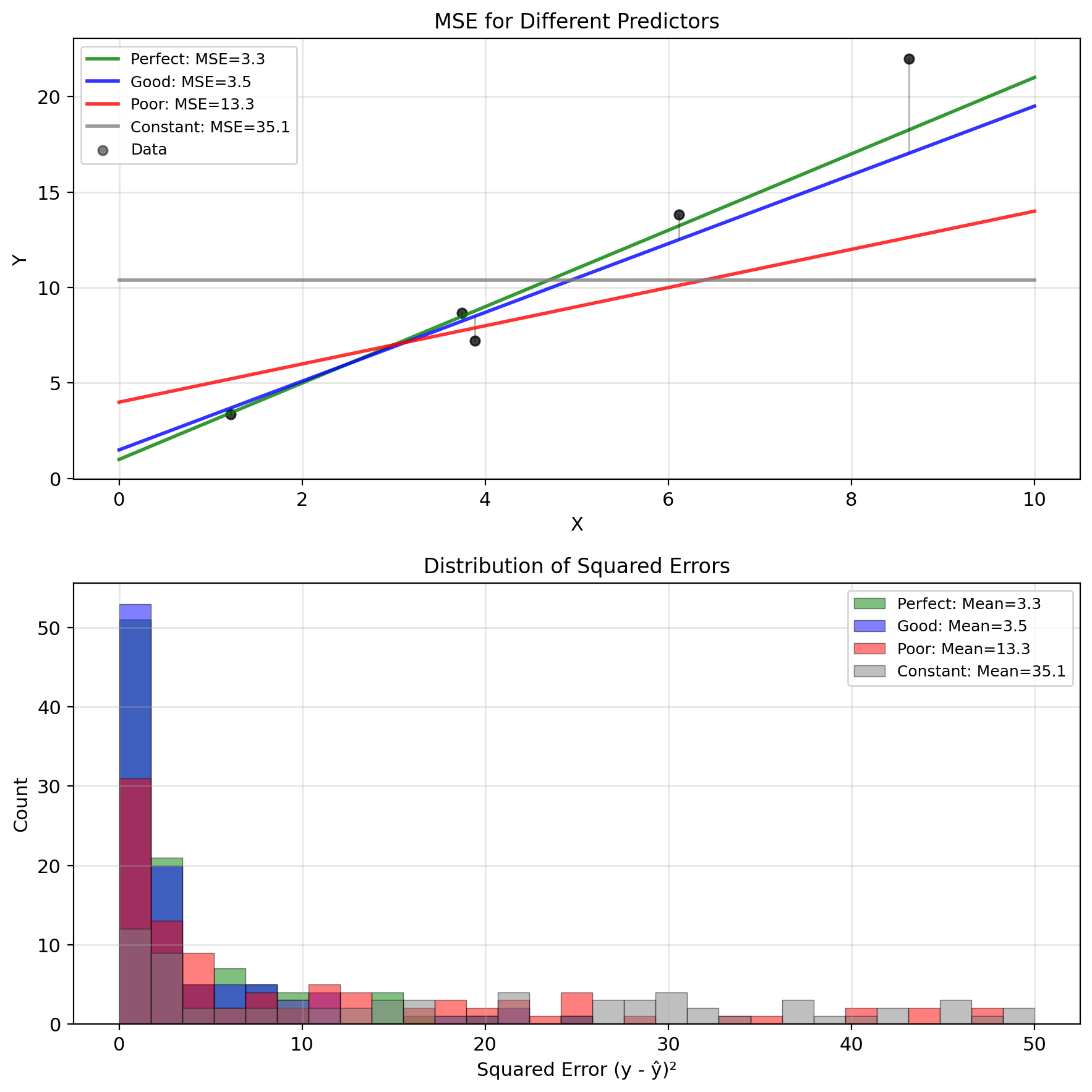

MSE = Bias² + Variance

Definition: \[\text{MSE}(g) = \mathbb{E}[(Y - g(X))^2]\]

Expanding the expectation: \[\text{MSE}(g) = \int\int (y - g(x))^2 p(x,y) \, dx \, dy\]

Empirical MSE (from data): \[\widehat{\text{MSE}} = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n (y_i - g(x_i))^2\]

Properties:

- Always non-negative: MSE ≥ 0

- Zero iff perfect prediction: MSE = 0 ⟺ P(Y = g(X)) = 1

- Units: [MSE] = [Y]²

Other forms:

- RMSE = √MSE (same units as Y)

- Normalized MSE = MSE/Var(Y)

- \(\rho^2\) = 1 - MSE/Var(Y)

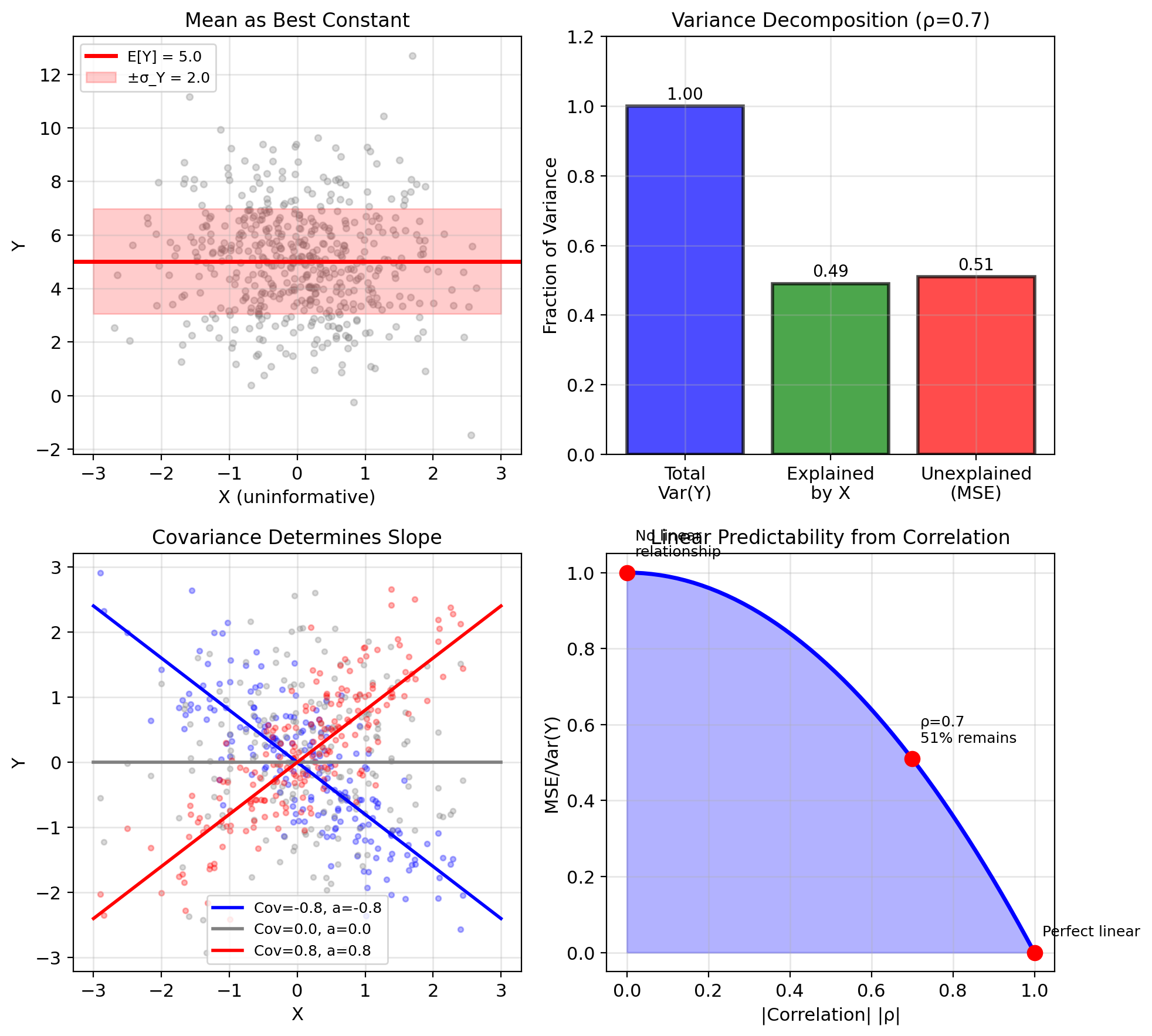

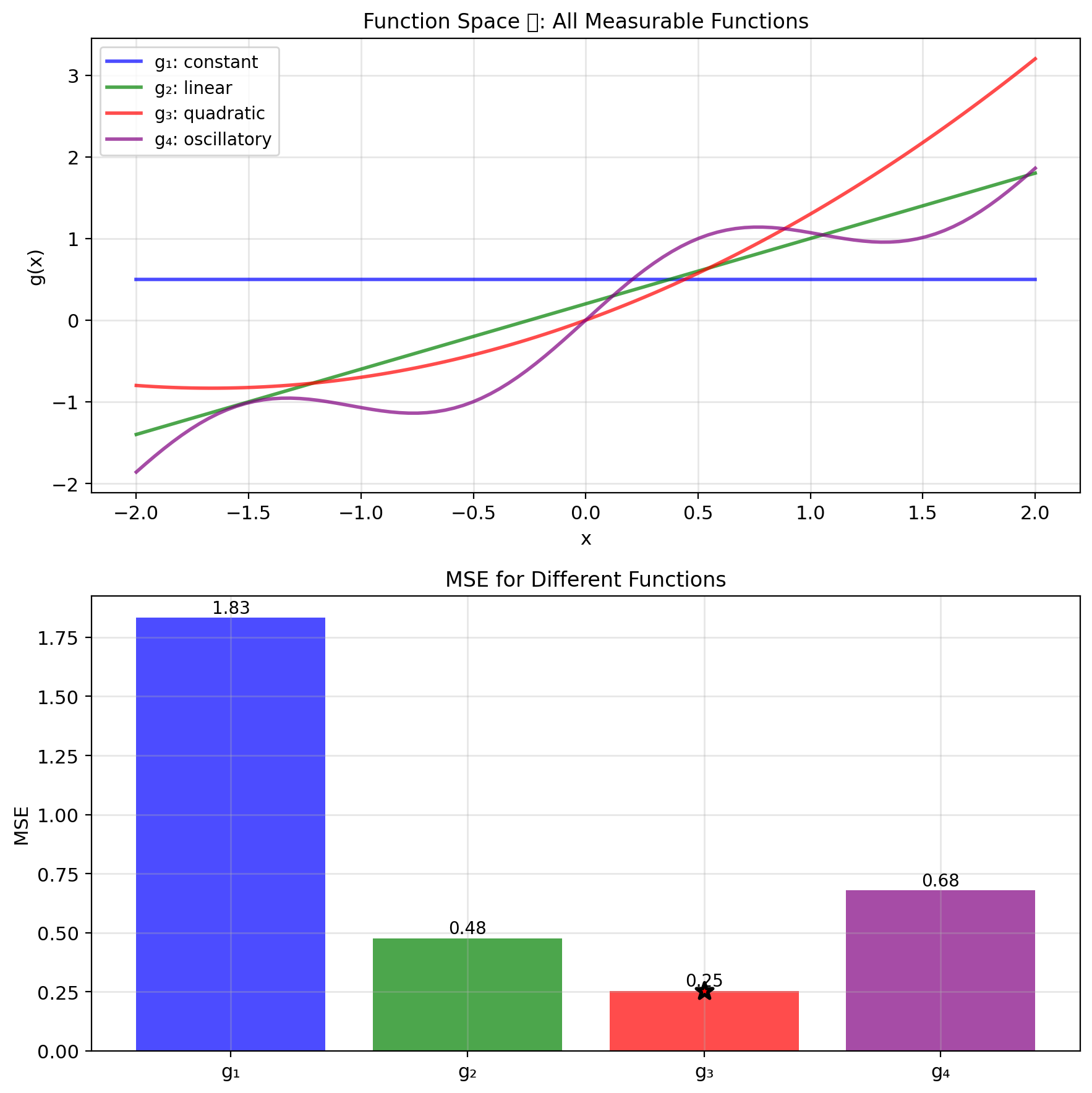

More Flexible = Harder to Optimize

Hierarchy of function classes:

- Constant: \(\hat{Y} = c\)

- Ignores observation X

- Optimal: \(c^* = \mathbb{E}[Y]\)

- MSE = Var(Y)

- Linear (affine): \(\hat{Y} = aX + b\)

- Simple, interpretable

- Only two parameters to optimize

- Many relationships are approximately linear

- Polynomial: \(\hat{Y} = \sum_{k=0}^p a_k X^k\)

- More flexible

- Risk of overfitting

- Unrestricted: \(\hat{Y} = g(X)\)

- Any measurable function

- Maximum flexibility

- Requires knowing \(p(y|x)\)

Flexibility vs Tractability

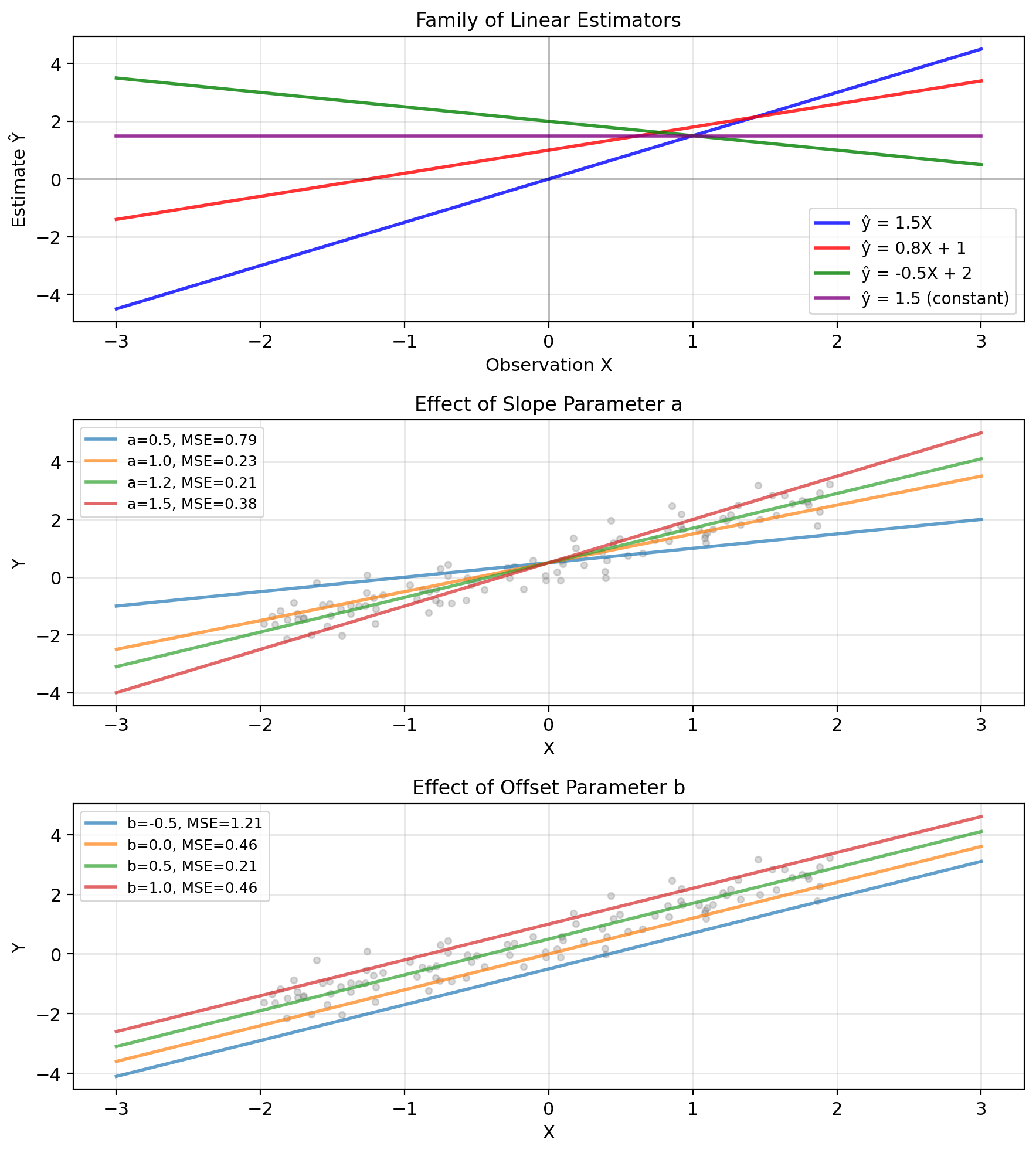

Linear Estimators: ŷ = aX + b

Definition: A linear estimator has the form \[\hat{Y} = aX + b\] where \(a, b \in \mathbb{R}\) are constants.

Note: “Linear” means linear in \(X\), not linear in parameters.

- \(\hat{Y} = 3X + 2\) is linear (in \(X\))

- \(\hat{Y} = \beta X^2\) is NOT linear (quadratic in \(X\))

- Despite \(\beta\) appearing linearly!

Parameters:

- \(a\): slope/gain/sensitivity

- \(b\): offset/bias/intercept

Special cases:

- \(b = 0\): Proportional estimator \(\hat{Y} = aX\)

- \(a = 0\): Constant estimator \(\hat{Y} = b\)

- \(a = 1, b = 0\): Direct use \(\hat{Y} = X\)

Property: Superposition If \(\hat{Y}_1 = aX_1 + b\) and \(\hat{Y}_2 = aX_2 + b\), then: \[\alpha\hat{Y}_1 + \beta\hat{Y}_2 = a(\alpha X_1 + \beta X_2) + (\alpha + \beta)b\]

Matrix form (preview): \[\hat{\mathbf{y}} = \mathbf{A}\mathbf{x} + \mathbf{b}\]

Moments Suffice for Linear Prediction

Mean E[Y]: Baseline predictor

- Best constant estimate

- What to predict without observing \(X\)

- MSE = Var(Y) when ignoring observations

Variance Var(Y): Spread/uncertainty

- Total variation to explain

- Upper bound on MSE (constant predictor)

- Normalizes performance: R² = 1 - MSE/Var(Y)

Covariance Cov(X,Y): Linear relationship strength

- Determines optimal linear slope

- Zero → X doesn’t help linearly

- Sign → direction of relationship

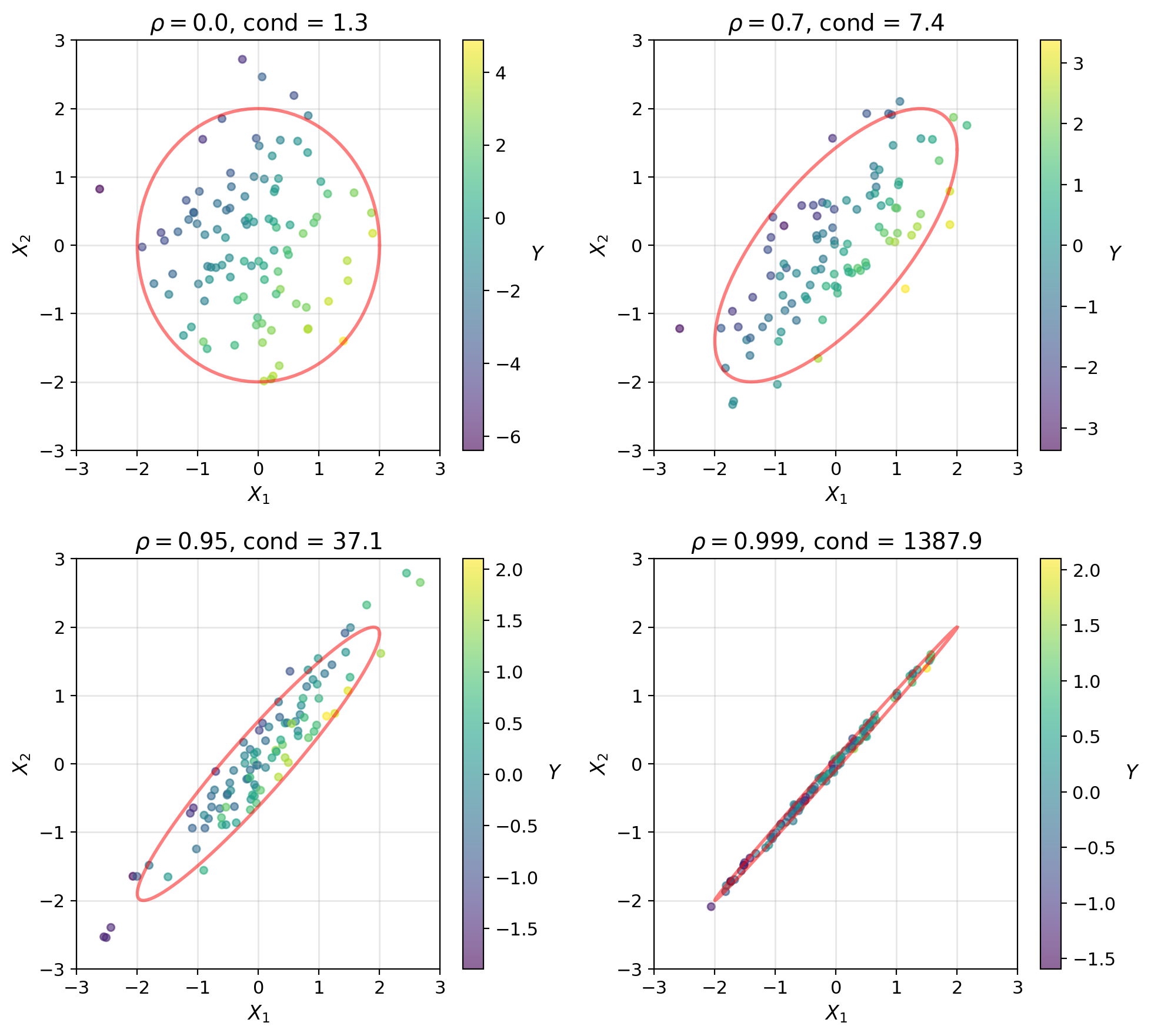

Correlation ρ: Normalized association

- Scale-free measure ∈ [-1, 1]

- |ρ| = 1 → perfect linear prediction possible

- ρ² = fraction of variance explained linearly

These moments completely determine the optimal linear estimator

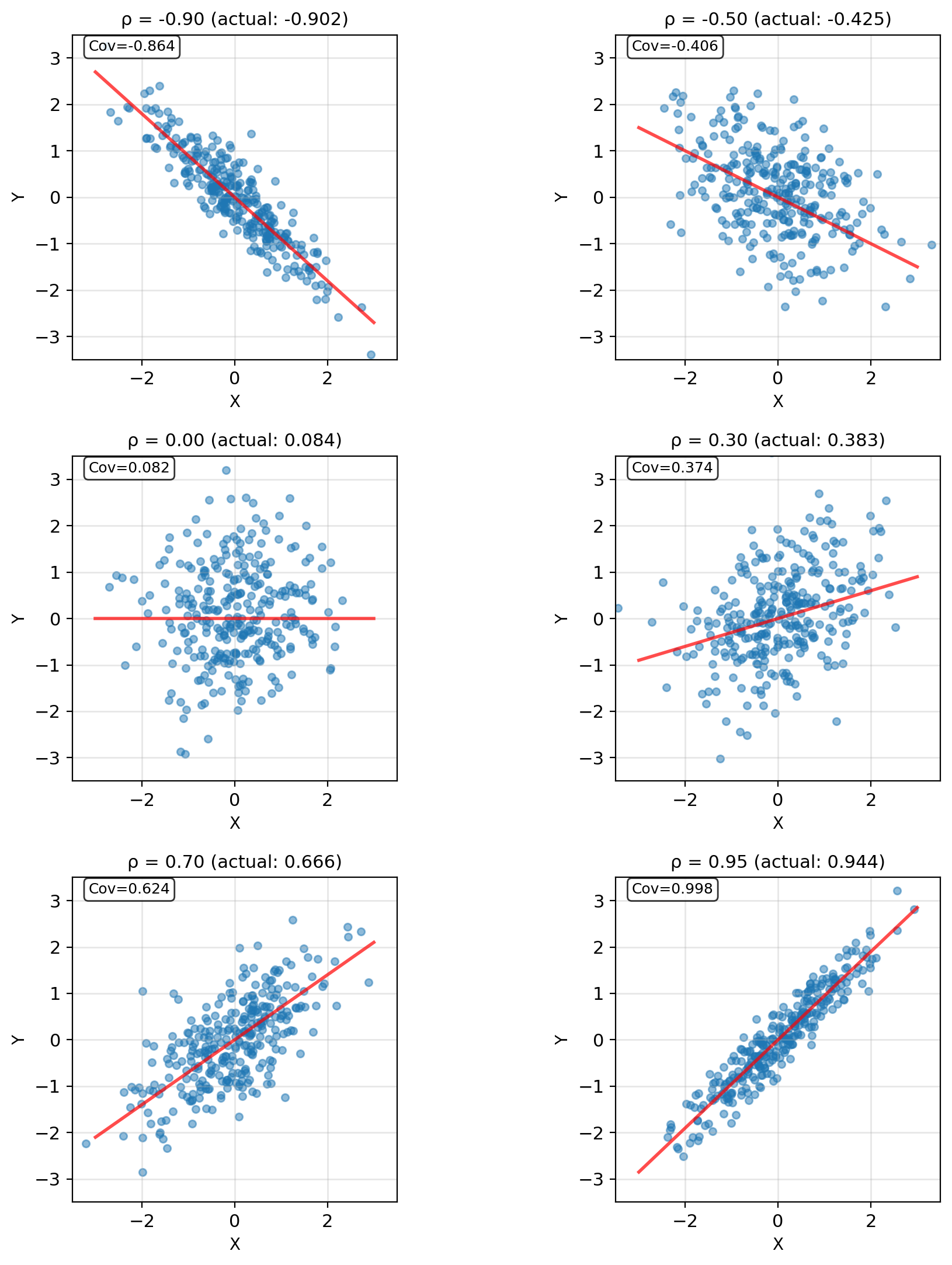

Covariance Quantifies Linear Dependence

First moments: \[\mathbb{E}[Y] = \int y \, p(y) \, dy\]

Second moments: \[\mathbb{E}[Y^2] = \int y^2 \, p(y) \, dy\]

Variance: \[\text{Var}(Y) = \mathbb{E}[(Y - \mathbb{E}[Y])^2] = \mathbb{E}[Y^2] - (\mathbb{E}[Y])^2\]

Covariance: \[\text{Cov}(X,Y) = \mathbb{E}[(X - \mathbb{E}[X])(Y - \mathbb{E}[Y])]\] \[= \mathbb{E}[XY] - \mathbb{E}[X]\mathbb{E}[Y]\]

Correlation coefficient: \[\rho_{XY} = \frac{\text{Cov}(X,Y)}{\sqrt{\text{Var}(X)\text{Var}(Y)}} \in [-1, 1]\]

- \(|\rho| = 1\): Perfect linear relationship

- \(\rho = 0\): Uncorrelated (not necessarily independent!)

- Sign indicates direction

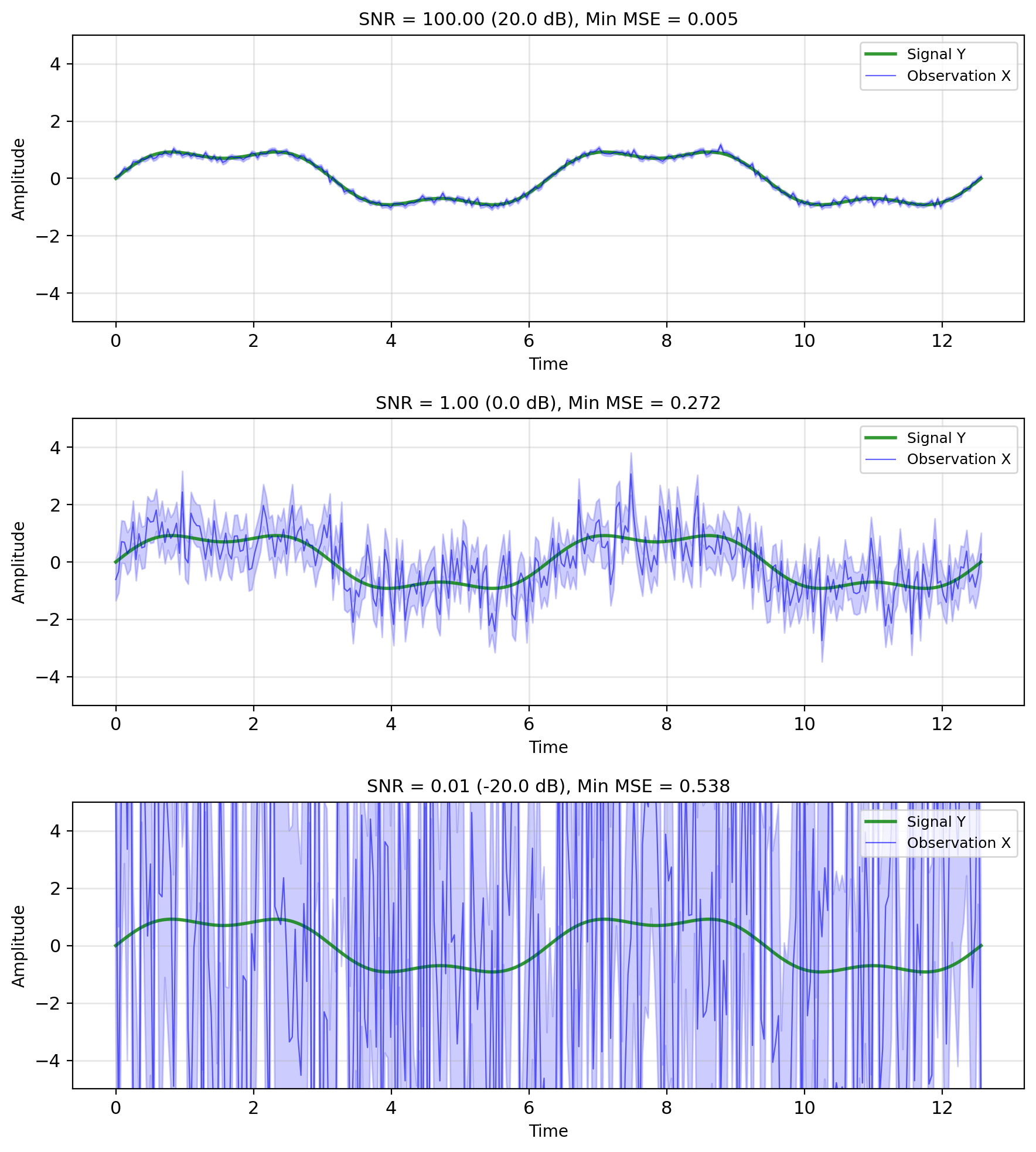

SNR Limits Achievable MSE

Additive noise model: \[X = Y + N\]

- \(Y\): true signal (what we want)

- \(N\): noise (corruption)

- \(X\): observation (what we get)

- Independence: \(Y \perp N\)

Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR): \[\text{SNR} = \frac{\text{Power}(Y)}{\text{Power}(N)} = \frac{\mathbb{E}[Y^2]}{\mathbb{E}[N^2]}\]

For zero-mean: \[\text{SNR} = \frac{\sigma_Y^2}{\sigma_N^2}\]

In dB: \(\text{SNR}_{\text{dB}} = 10\log_{10}(\text{SNR})\)

Fundamental limit: Even with optimal estimation, cannot remove all noise: \[\text{MSE}_{\text{min}} \geq \frac{\sigma_Y^2 \sigma_N^2}{\sigma_Y^2 + \sigma_N^2} = \frac{\sigma_Y^2}{1 + \text{SNR}}\]

Probability Review

Random Variables Map Outcomes to Numbers

Sample space \(\Omega\): Set of all possible outcomes

Random variable \(X: \Omega \to \mathbb{R}\)

Maps each outcome to a real number.

Notation convention:

- \(X\) (uppercase): The random variable (a function)

- \(x\) (lowercase): A specific realized value

Discrete example: Die roll

- \(\Omega = \{\omega_1, \omega_2, \omega_3, \omega_4, \omega_5, \omega_6\}\)

- \(X(\omega_i) = i\)

- \(P(X = 3) = 1/6\)

Continuous example: Measurement noise

- \(\Omega\) = all possible noise realizations

- \(X(\omega)\) = voltage at time \(t\)

- \(P(X = 1.5)\) = 0, but \(P(1.4 < X < 1.6) > 0\)

Joint Distributions Capture Relationships Between Variables

Joint distribution \(p(x, y)\):

Probability (density) that \(X = x\) AND \(Y = y\) simultaneously.

For discrete: \(P(X = x, Y = y)\)

For continuous: \(p(x,y)\) where \[P(a < X < b, c < Y < d) = \int_a^b \int_c^d p(x,y) \, dy \, dx\]

What the joint tells you:

- How likely are specific \((x, y)\) pairs?

- Are \(X\) and \(Y\) related or independent?

- Everything about marginals and conditionals

Independence means: \[p(x, y) = p(x) \cdot p(y)\]

Joint factors into product of marginals.

Marginals and Conditionals From the Joint

Marginal distribution: Integrate out what you don’t need

\[p(x) = \int p(x, y) \, dy\]

\[p(y) = \int p(x, y) \, dx\]

Conditional distribution: Slice and renormalize

\[p(y|x) = \frac{p(x, y)}{p(x)}\]

Bayes’ rule is just rearranging:

\[p(y|x) = \frac{p(x|y) \, p(y)}{p(x)}\]

Computational view:

- Start with joint \(p(x,y)\)

- Fix \(x\) to get a slice

- Divide by \(p(x)\) to make it integrate to 1

This is conditioning as a mechanical operation.

Expectation Is a Weighted Average

Discrete: \[\mathbb{E}[X] = \sum_x x \cdot P(X = x)\]

Continuous: \[\mathbb{E}[X] = \int x \cdot p(x) \, dx\]

Interpretation: Center of mass of the distribution

Expectation of a function: \[\mathbb{E}[g(X)] = \int g(x) \cdot p(x) \, dx\]

Example: Die roll

\(\mathbb{E}[X] = 1 \cdot \frac{1}{6} + 2 \cdot \frac{1}{6} + \cdots + 6 \cdot \frac{1}{6} = 3.5\)

Note: 3.5 is not a possible outcome, but it’s the long-run average.

Linearity of Expectation Holds for Any Joint Distribution

Linearity: \[\mathbb{E}[aX + bY] = a\mathbb{E}[X] + b\mathbb{E}[Y]\]

This holds even if \(X\) and \(Y\) are dependent.

Why? Just rearranging sums/integrals: \[\mathbb{E}[X + Y] = \int\int (x + y) p(x,y) \, dx \, dy\] \[= \int\int x \, p(x,y) \, dx \, dy + \int\int y \, p(x,y) \, dx \, dy\] \[= \int x \, p(x) \, dx + \int y \, p(y) \, dy\] \[= \mathbb{E}[X] + \mathbb{E}[Y]\]

Example: Sum of two dice

\(\mathbb{E}[X_1 + X_2] = \mathbb{E}[X_1] + \mathbb{E}[X_2] = 3.5 + 3.5 = 7\)

No need to enumerate all 36 outcomes.

Variance Measures Spread Around the Mean

Definition: \[\text{Var}(X) = \mathbb{E}[(X - \mu)^2]\]

where \(\mu = \mathbb{E}[X]\)

Computational form: \[\text{Var}(X) = \mathbb{E}[X^2] - (\mathbb{E}[X])^2\]

When to use which:

- Definition: Intuition (average squared deviation from mean)

- Computational: Calculation (often simpler)

Standard deviation: \(\sigma = \sqrt{\text{Var}(X)}\)

Same units as \(X\) (variance has squared units)

Properties:

- \(\text{Var}(X) \geq 0\)

- \(\text{Var}(aX + b) = a^2 \text{Var}(X)\)

- Adding constant shifts mean, doesn’t change spread

Covariance Measures Linear Co-Movement

Definition: \[\text{Cov}(X, Y) = \mathbb{E}[(X - \mu_X)(Y - \mu_Y)]\]

Computational form: \[\text{Cov}(X, Y) = \mathbb{E}[XY] - \mathbb{E}[X]\mathbb{E}[Y]\]

Interpretation:

- \(\text{Cov} > 0\): When \(X\) is above its mean, \(Y\) tends to be above its mean

- \(\text{Cov} < 0\): When \(X\) is above its mean, \(Y\) tends to be below its mean

- \(\text{Cov} = 0\): No linear relationship

Correlation (normalized covariance): \[\rho = \frac{\text{Cov}(X,Y)}{\sigma_X \sigma_Y} \in [-1, 1]\]

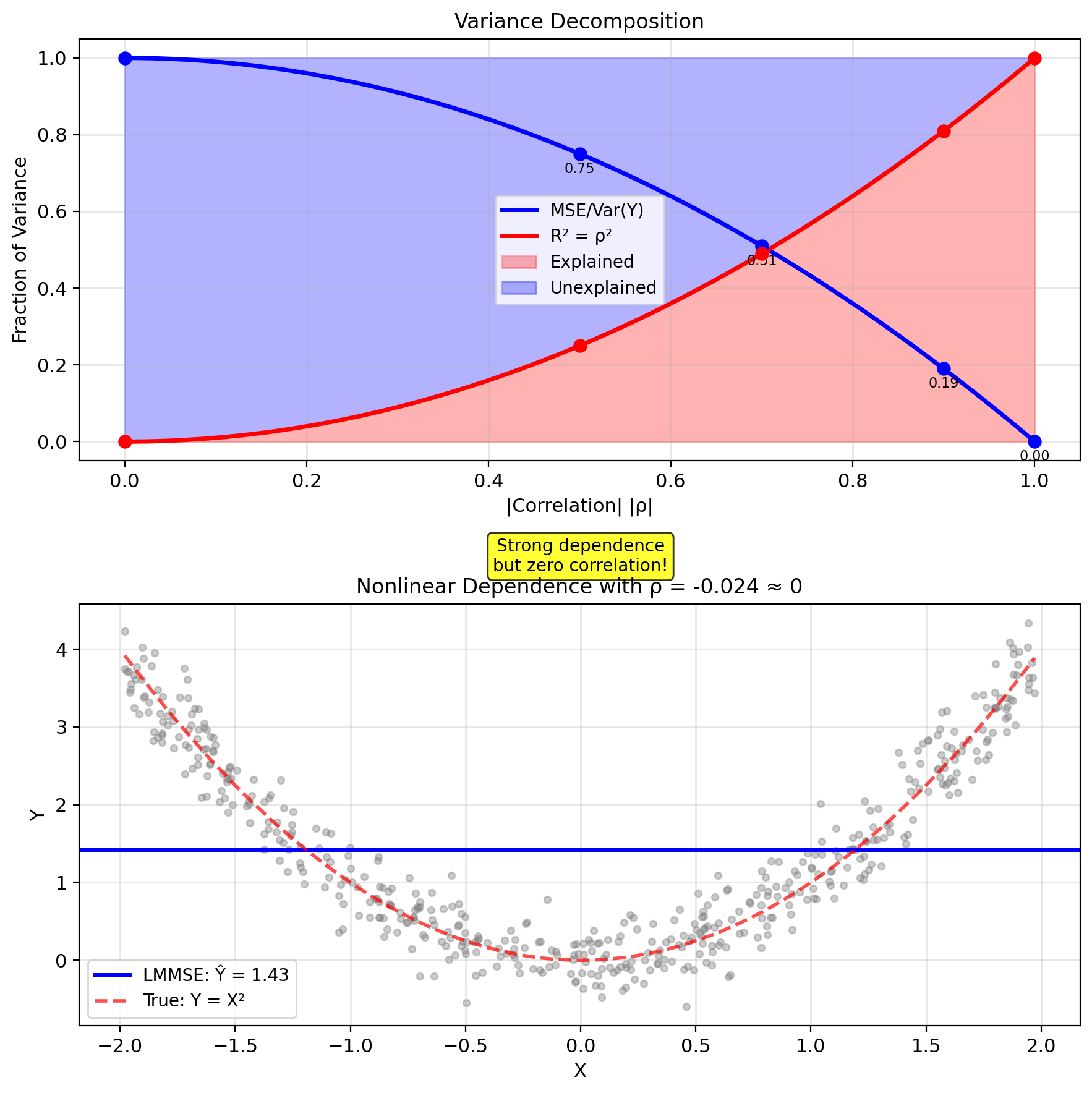

Important: \(\text{Cov}(X,Y) = 0\) does NOT imply independence.

\(Y = X^2\) with \(X \sim \mathcal{N}(0,1)\): clearly dependent, but \(\text{Cov}(X, Y) = 0\).

Variance of Sums Depends on Covariance

For two random variables: \[\text{Var}(X + Y) = \text{Var}(X) + \text{Var}(Y) + 2\text{Cov}(X, Y)\]

If uncorrelated (\(\text{Cov}(X,Y) = 0\)): \[\text{Var}(X + Y) = \text{Var}(X) + \text{Var}(Y)\]

Contrast with expectation:

- \(\mathbb{E}[X + Y] = \mathbb{E}[X] + \mathbb{E}[Y]\) always

- \(\text{Var}(X + Y) = \text{Var}(X) + \text{Var}(Y)\) only if uncorrelated

General form: \[\text{Var}\left(\sum_i a_i X_i\right) = \sum_i a_i^2 \text{Var}(X_i) + 2\sum_{i < j} a_i a_j \text{Cov}(X_i, X_j)\]

Why this matters: Diversification in portfolios, error propagation, averaging measurements

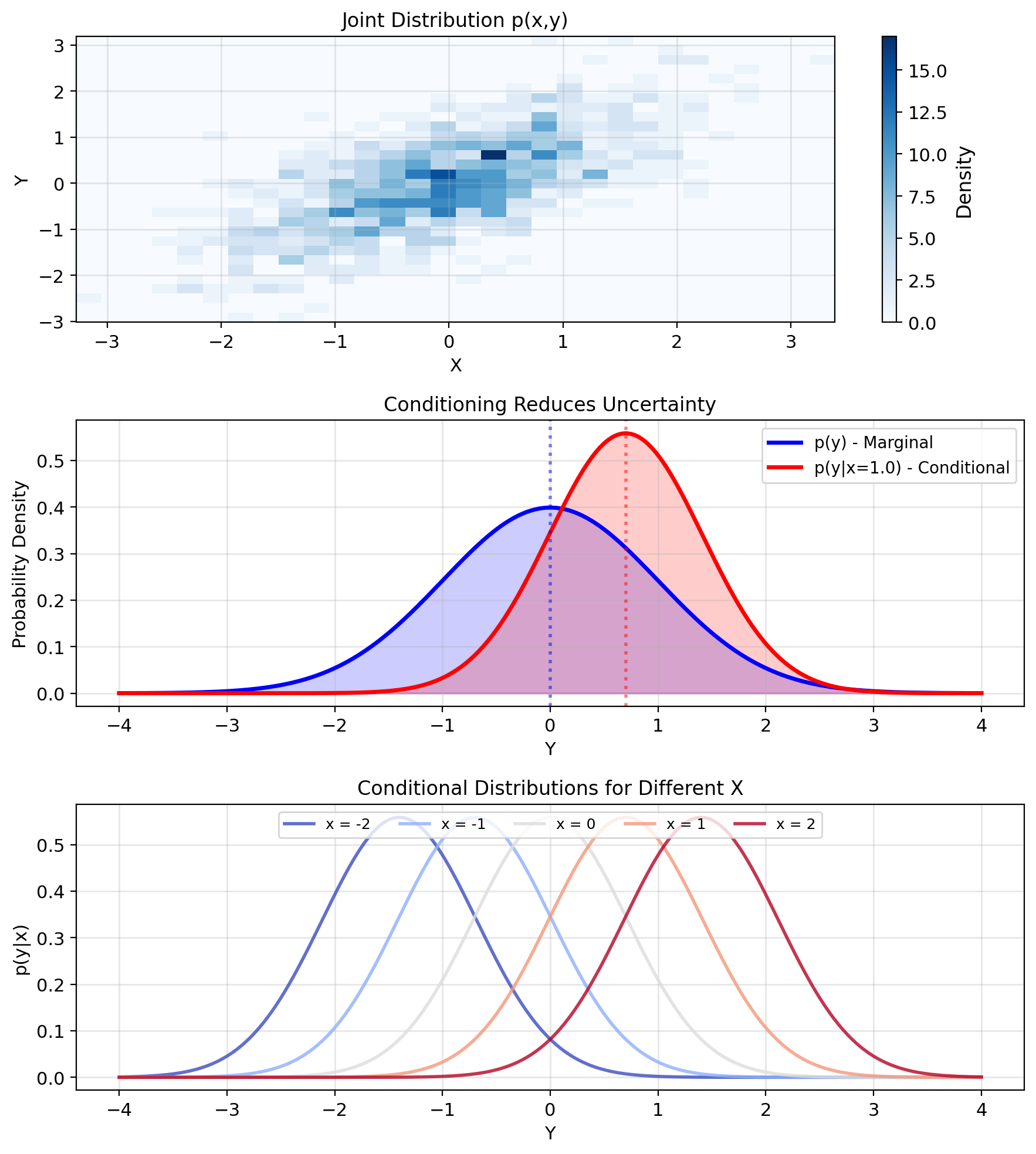

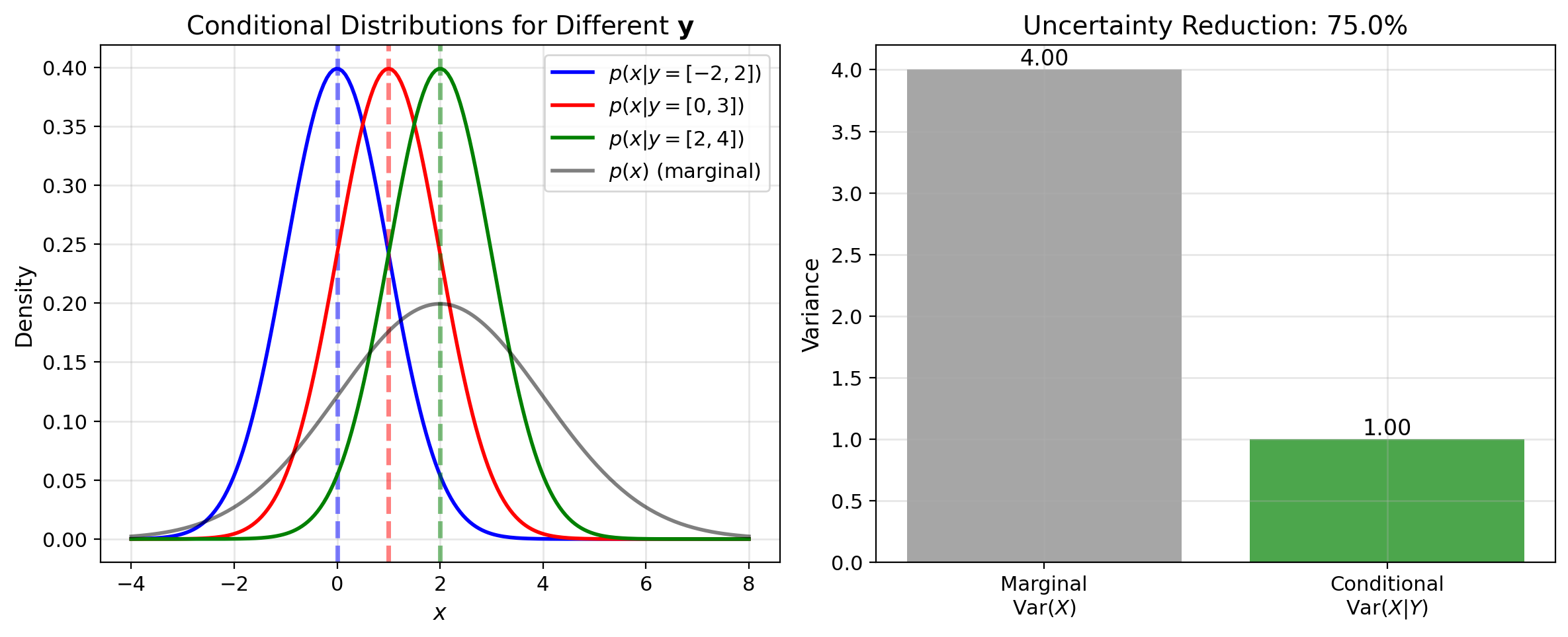

Conditioning Concentrates Probability

Observations Shrink the Distribution

Joint distribution \((X, Y) \sim p(x,y)\) contains all information.

Bayes’ rule: \[p(y|x) = \frac{p(x,y)}{p(x)} = \frac{p(x,y)}{\int p(x,y') dy'}\]

Once we observe \(X = x\), the distribution of \(Y\) changes from \(p(y)\) to \(p(y|x)\).

Example: Temperature sensor

- Prior: \(Y \sim \mathcal{N}(70, 10^2)\) (before measurement)

- Observe: \(X = 75\) (sensor reading)

- Posterior: \(Y|X=75 \sim \mathcal{N}(73, 4^2)\) (after measurement)

Conditioning incorporates information, reducing spread.

Conditioning reduces uncertainty

Discrete case: \[P(Y = y|X = x) = \frac{P(X = x, Y = y)}{P(X = x)}\]

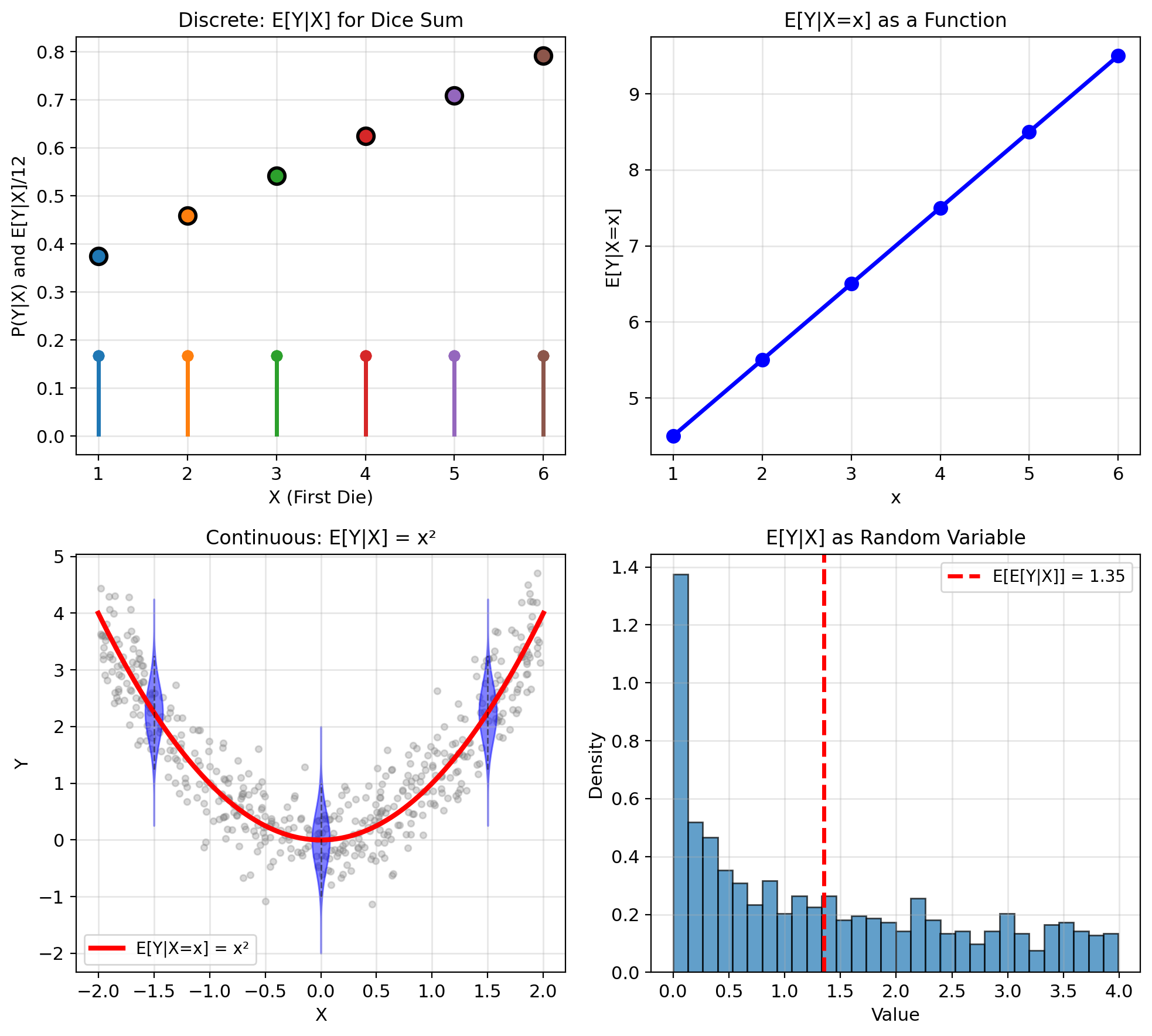

E[Y|X=x] Is a Number; E[Y|X] Is a Random Variable

Definition: The conditional expectation of \(Y\) given \(X = x\) is:

Discrete case: \[\mathbb{E}[Y|X=x] = \sum_y y \cdot P(Y=y|X=x)\]

Continuous case: \[\mathbb{E}[Y|X=x] = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} y \cdot p(y|x) \, dy\]

Facts:

- \(\mathbb{E}[Y|X=x]\) is a number (for fixed \(x\))

- expectation when \(X\) equals \(x\)

- \(\mathbb{E}[Y|X]\) is a random variable (function of \(X\))

- \(g(x) = \mathbb{E}[Y|X=x]\) is a deterministic function

Example: \(Y = X + N\), \(N \sim \mathcal{N}(0,1)\), independent \(X\) and \(N\) \[\mathbb{E}[Y|X=x] = \mathbb{E}[x + N] = x\]

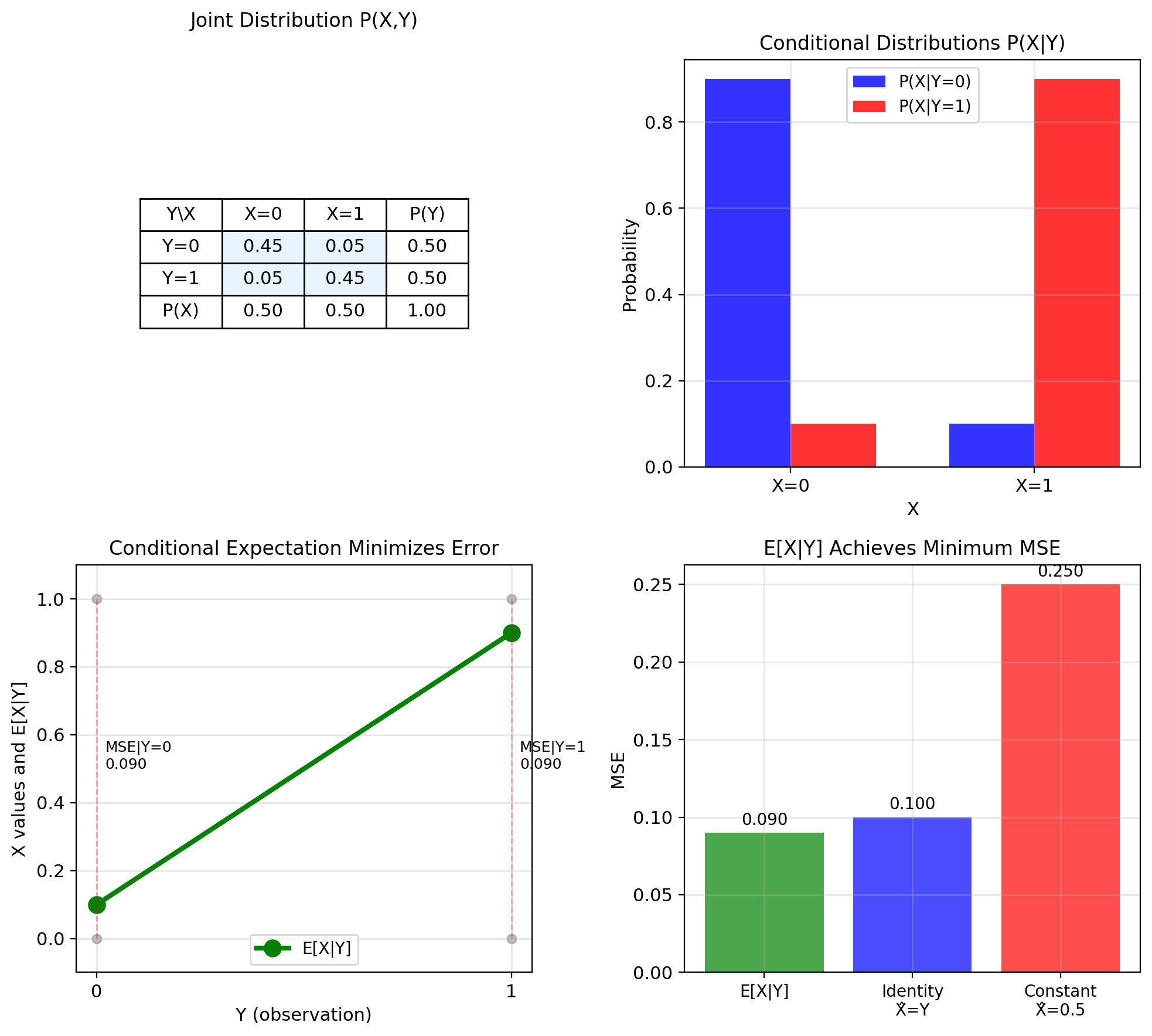

Binary Channel: E[X|Y] Achieves Minimum MSE

Example: Binary communication channel

- \(X \in \{0, 1\}\): transmitted bit

- \(Y \in \{0, 1\}\): received bit

- Channel flips bit with probability \(p = 0.1\)

Joint distribution: \[P(X=0, Y=0) = 0.45, \quad P(X=1, Y=0) = 0.05\] \[P(X=0, Y=1) = 0.05, \quad P(X=1, Y=1) = 0.45\]

Conditional distributions: \[P(X=0|Y=0) = \frac{0.45}{0.5} = 0.9\] \[P(X=1|Y=0) = \frac{0.05}{0.5} = 0.1\]

Conditional expectations: \[\mathbb{E}[X|Y=0] = 0 \cdot 0.9 + 1 \cdot 0.1 = 0.1\] \[\mathbb{E}[X|Y=1] = 0 \cdot 0.1 + 1 \cdot 0.9 = 0.9\]

MSE for different predictors:

- \(\hat{X} = \mathbb{E}[X|Y]\): MSE = 0.09

- \(\hat{X} = Y\) (identity): MSE = 0.10

- \(\hat{X} = 0.5\) (constant): MSE = 0.25

Result: \(\mathbb{E}[X|Y]\) achieves minimum MSE

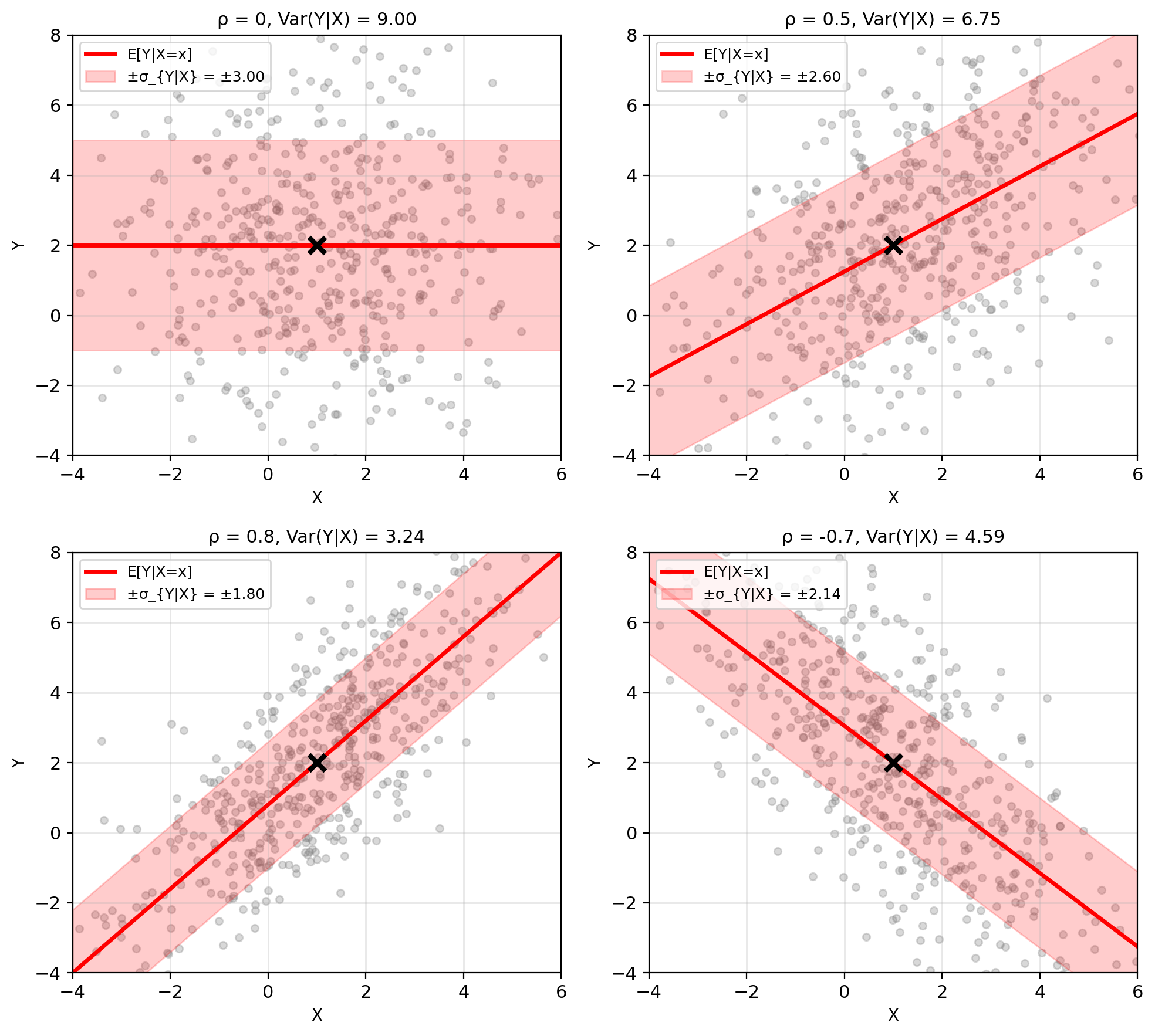

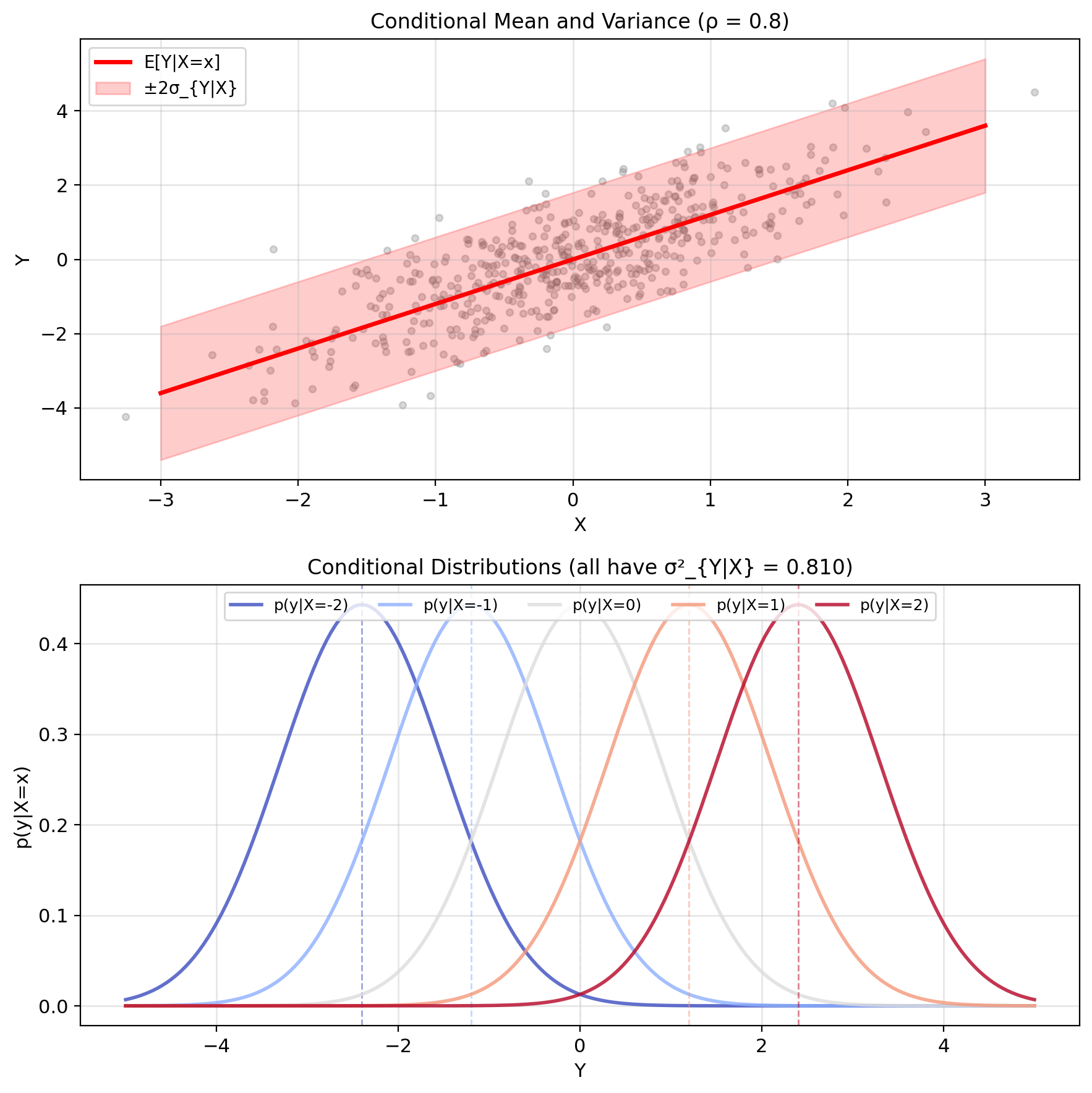

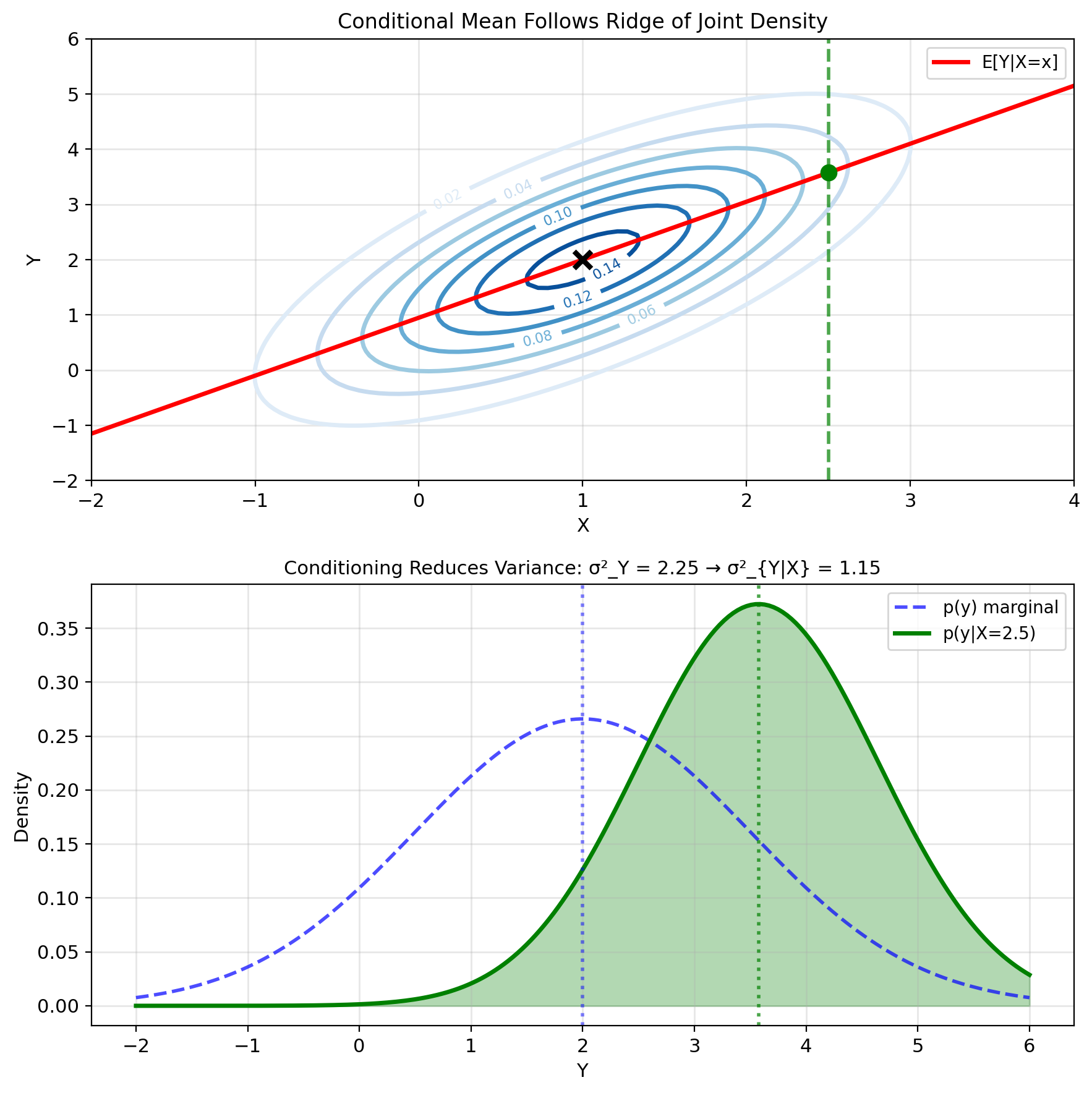

Gaussian Conditional Mean Is Linear in X

Joint Gaussian: \((X, Y) \sim \mathcal{N}(\mu, K)\)

Parameters: \[\mu = \begin{bmatrix} \mu_X \\ \mu_Y \end{bmatrix}, \quad K = \begin{bmatrix} \sigma_X^2 & \rho\sigma_X\sigma_Y \\ \rho\sigma_X\sigma_Y & \sigma_Y^2 \end{bmatrix}\]

Result (derive later): \[\mathbb{E}[Y|X=x] = \mu_Y + \rho\frac{\sigma_Y}{\sigma_X}(x - \mu_X)\]

Properties:

- Linear in \(x\) (always!)

- Slope = \(\rho\sigma_Y/\sigma_X\)

- Passes through \((\mu_X, \mu_Y)\)

- \(|\rho| = 1 \Rightarrow\) perfect prediction

Conditional variance (constant!): \[\text{Var}(Y|X=x) = \sigma_Y^2(1 - \rho^2)\]

Independent of \(x\) - uncertainty same everywhere.

Special cases:

- \(\rho = 0\): \(\mathbb{E}[Y|X=x] = \mu_Y\) (no information)

- \(|\rho| = 1\): \(\text{Var}(Y|X) = 0\) (perfect prediction)

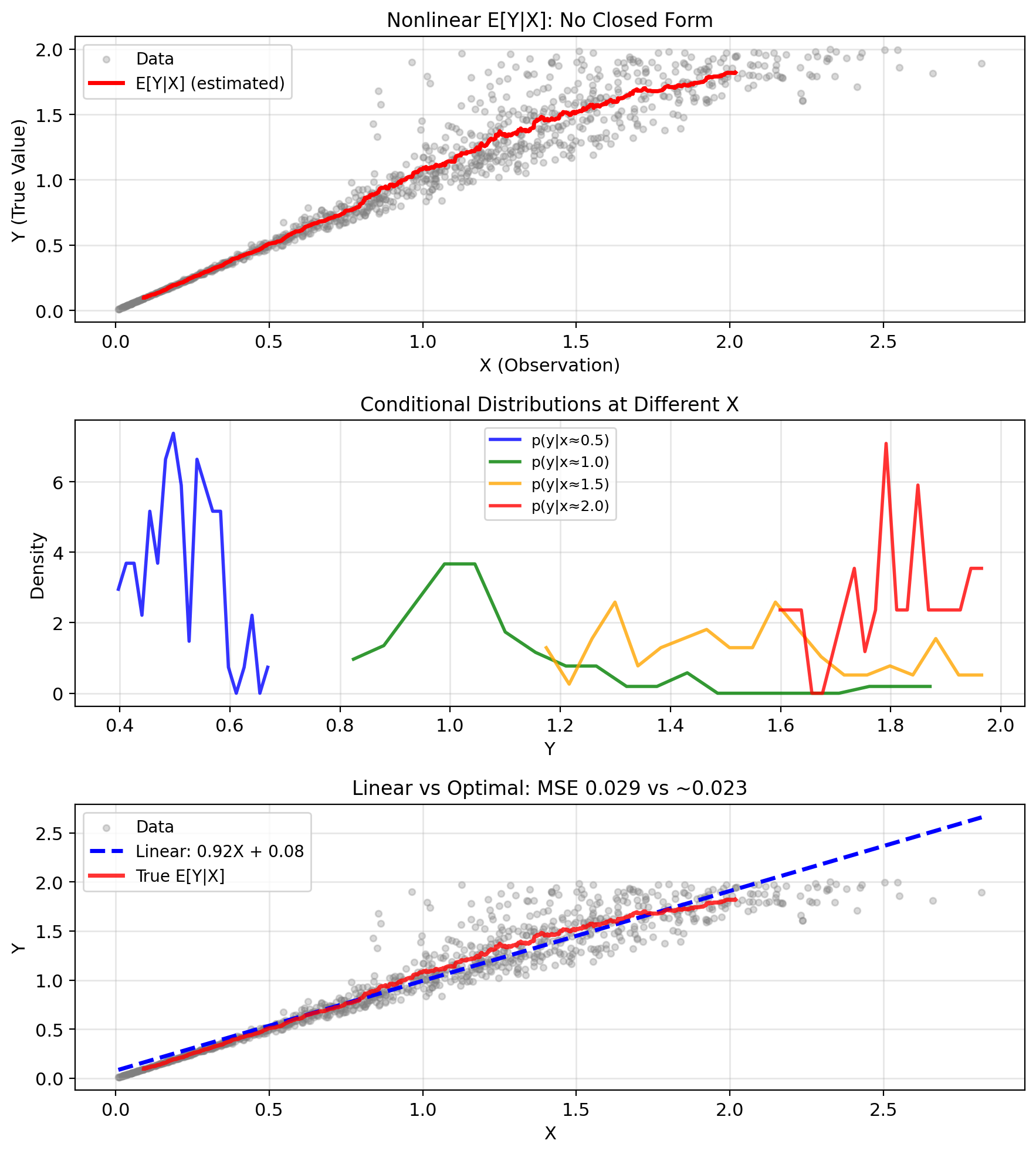

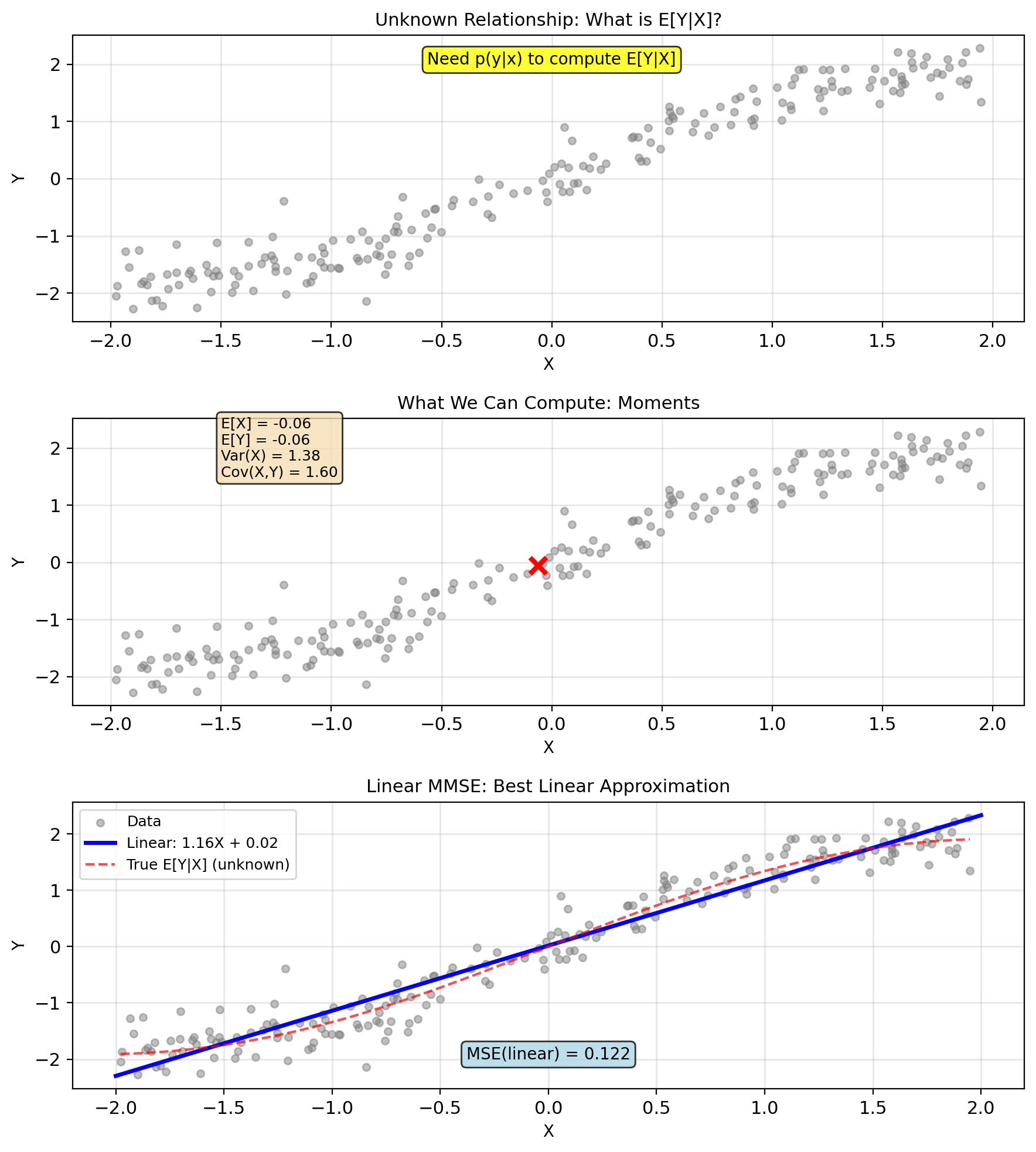

E[Y|X] Requires the Conditional Density

Computing \(\mathbb{E}[Y|X=x]\) requires \(p(y|x)\)

From Bayes: \[p(y|x) = \frac{p(x,y)}{p(x)} = \frac{p(x|y)p(y)}{\int p(x|y')p(y')dy'}\]

When tractable:

- Known parametric families (Gaussian, exponential)

- Discrete with small state space

- Special structures (independence, Markov)

When intractable (often no closed form):

- Complex nonlinear relationships

- High dimensions

- Unknown distributions

Example: Nonlinear sensor \[Y = \text{true value}, \quad X = Y + Y^2 \cdot N\] where \(N \sim \mathcal{N}(0, 0.1)\)

Computing \(\mathbb{E}[Y|X=x]\) requires:

- Joint density \(p(x,y)\)

- Marginal \(p(x) = \int p(x,y)dy\)

- Conditional \(p(y|x) = p(x,y)/p(x)\)

- Integration \(\mathbb{E}[Y|X=x] = \int y p(y|x) dy\)

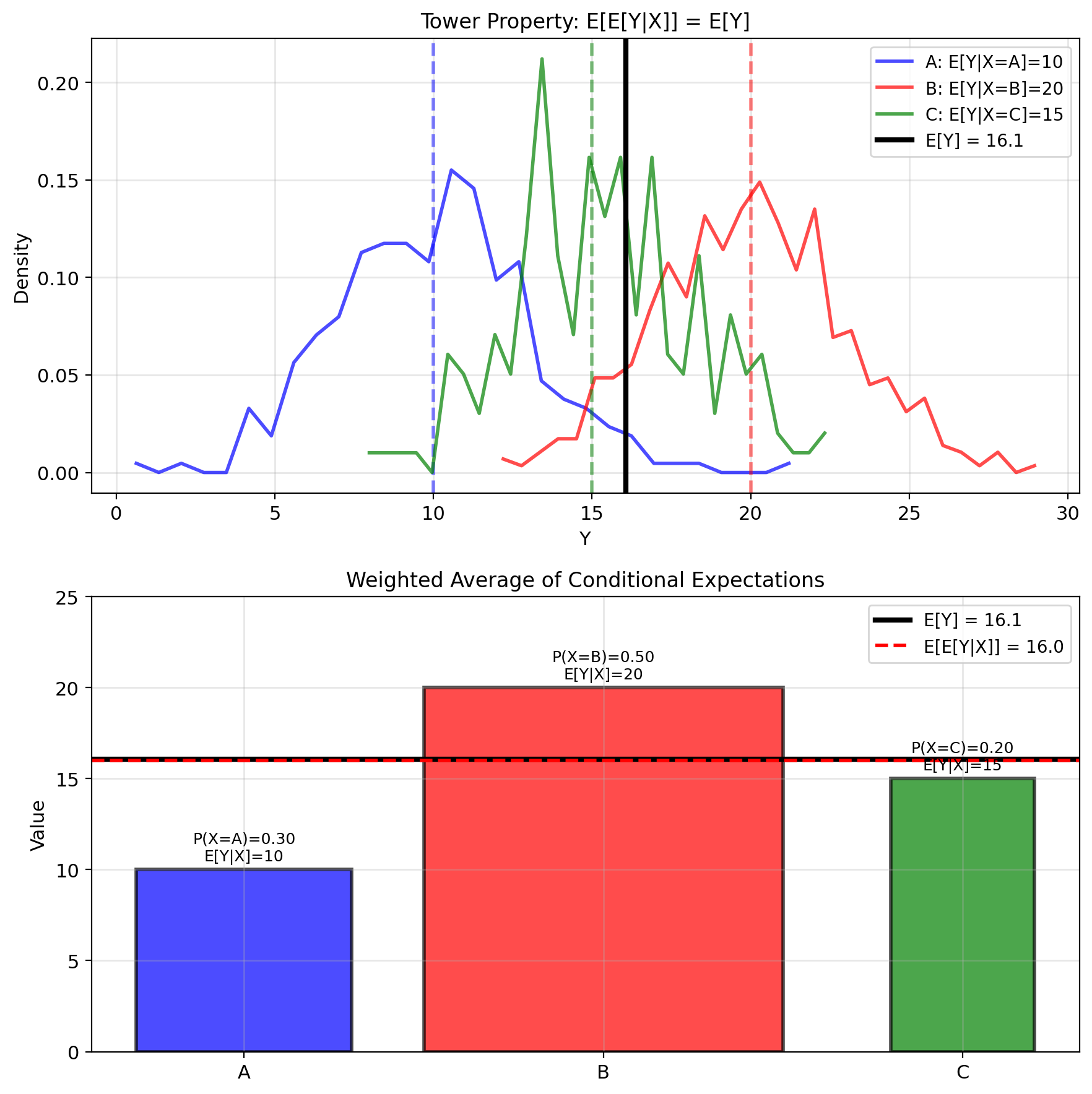

Iterated Expectations Recover the Mean

Law of Total Expectation: \[\mathbb{E}[\mathbb{E}[Y|X]] = \mathbb{E}[Y]\]

Proof: \[\mathbb{E}[\mathbb{E}[Y|X]] = \mathbb{E}[g(X)]\] where \(g(x) = \mathbb{E}[Y|X=x]\)

\[= \int g(x) p(x) dx = \int \mathbb{E}[Y|X=x] p(x) dx\]

\[= \int \left(\int y \, p(y|x) dy\right) p(x) dx\]

\[= \int\int y \, p(y|x) p(x) dy \, dx\]

\[= \int y \left(\int p(y|x)p(x) dx\right) dy\]

\[= \int y \, p(y) dy = \mathbb{E}[Y]\]

Intuition: Average of conditional averages = unconditional average

Example: Class grades

- Section A: mean 85, 30 students

- Section B: mean 75, 20 students

- Overall mean = \(\frac{30 \cdot 85 + 20 \cdot 75}{50} = 81\)

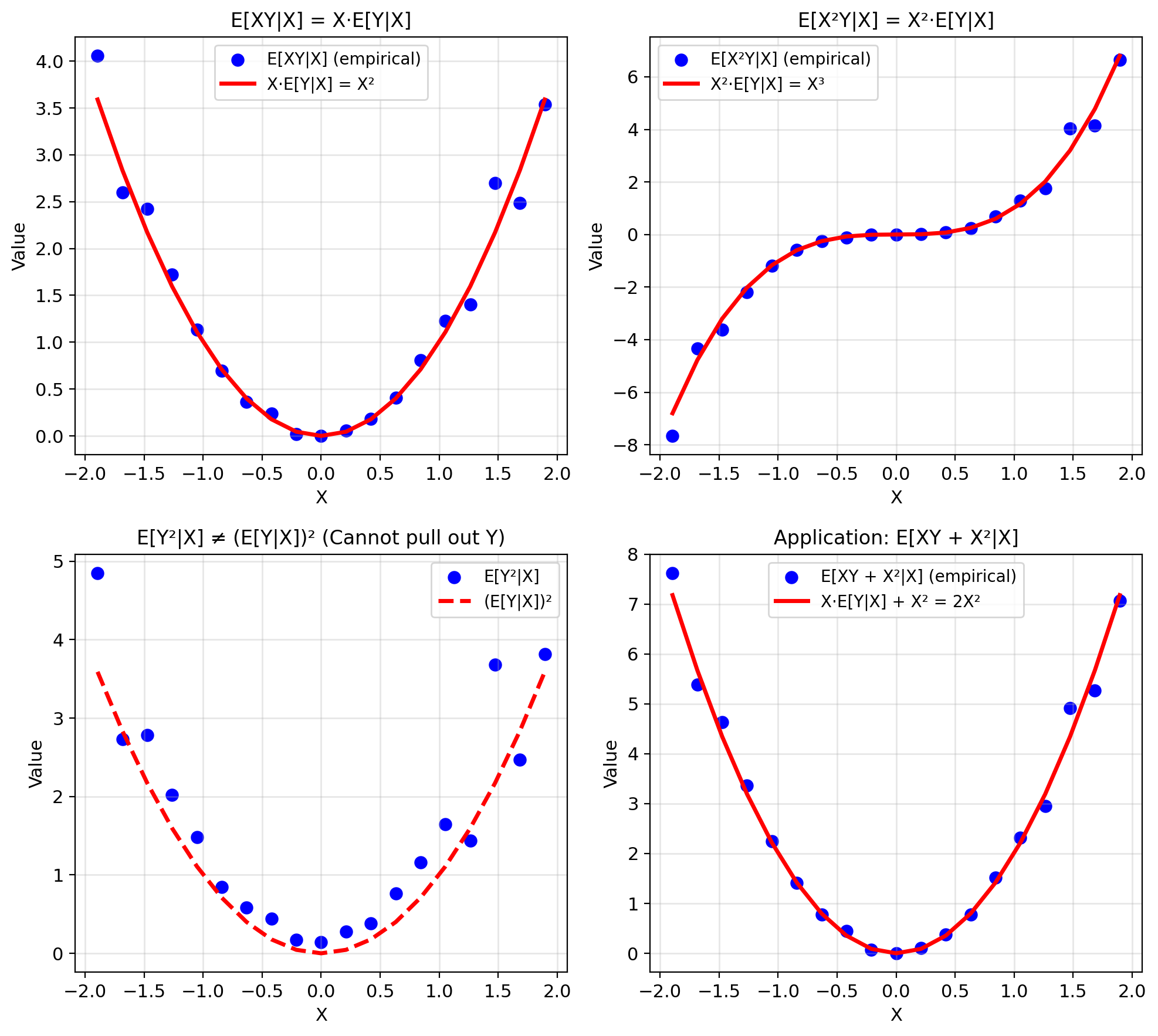

Functions of X Factor Out

Property: For any function \(h(X)\): \[\mathbb{E}[h(X)Y | X] = h(X)\mathbb{E}[Y|X]\]

Proof: Fix \(X = x\). Then \(h(X) = h(x)\) is a constant: \[\mathbb{E}[h(X)Y | X=x] = \mathbb{E}[h(x)Y | X=x]\] \[= h(x)\mathbb{E}[Y | X=x]\]

Special cases:

- \(\mathbb{E}[X \cdot Y | X] = X \cdot \mathbb{E}[Y|X]\)

- \(\mathbb{E}[f(X) + Y | X] = f(X) + \mathbb{E}[Y|X]\)

- \(\mathbb{E}[X^2Y | X] = X^2\mathbb{E}[Y|X]\)

Example: Signal processing \[Z = X \cdot Y + X^2\] \[\mathbb{E}[Z|X] = X\mathbb{E}[Y|X] + X^2\]

Only need \(\mathbb{E}[Y|X]\), not \(\mathbb{E}[XY|X]\)!

BUT: Cannot pull out functions of \(Y\): \[\mathbb{E}[Y^2|X] \neq Y \cdot \mathbb{E}[Y|X]\]

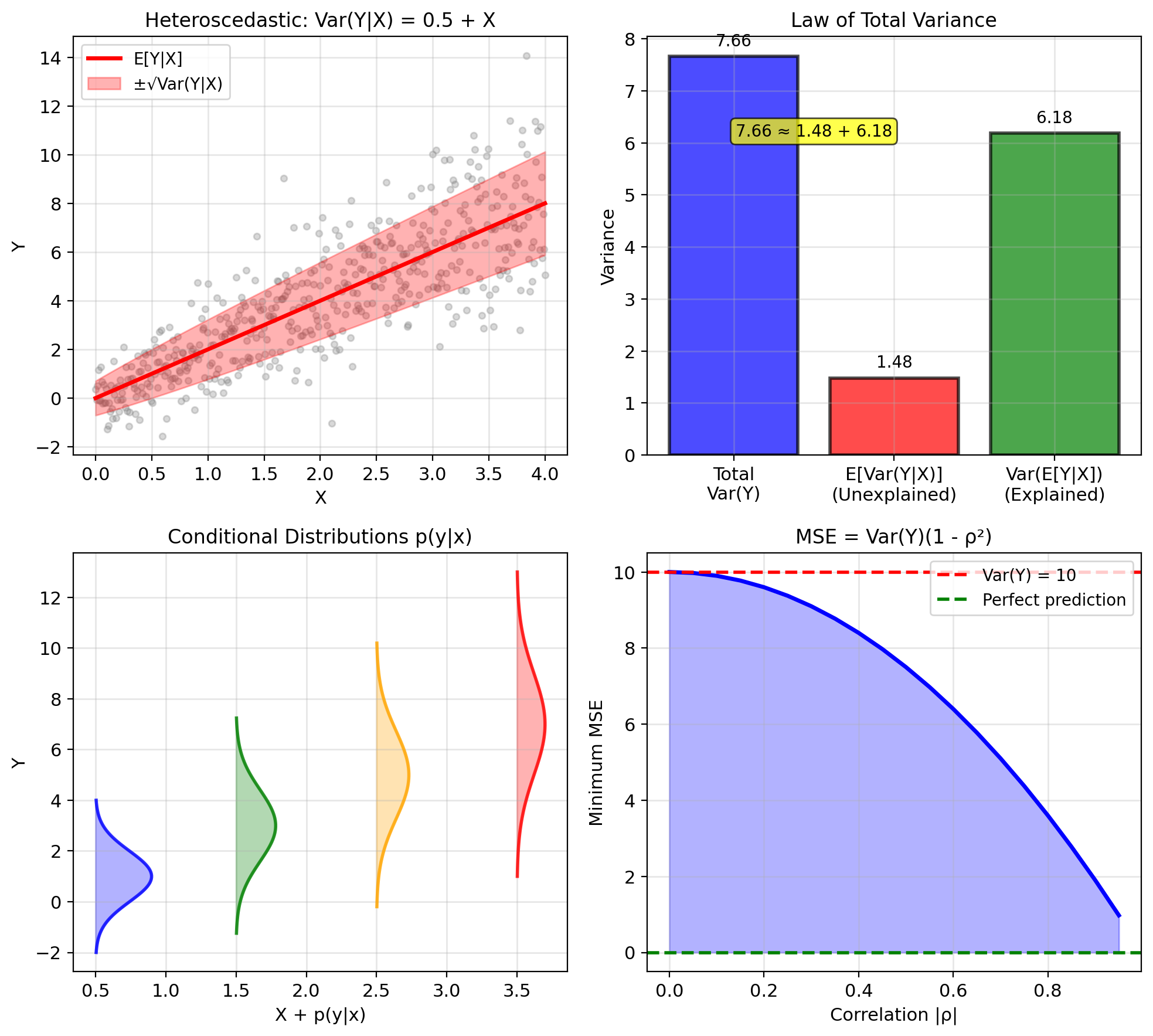

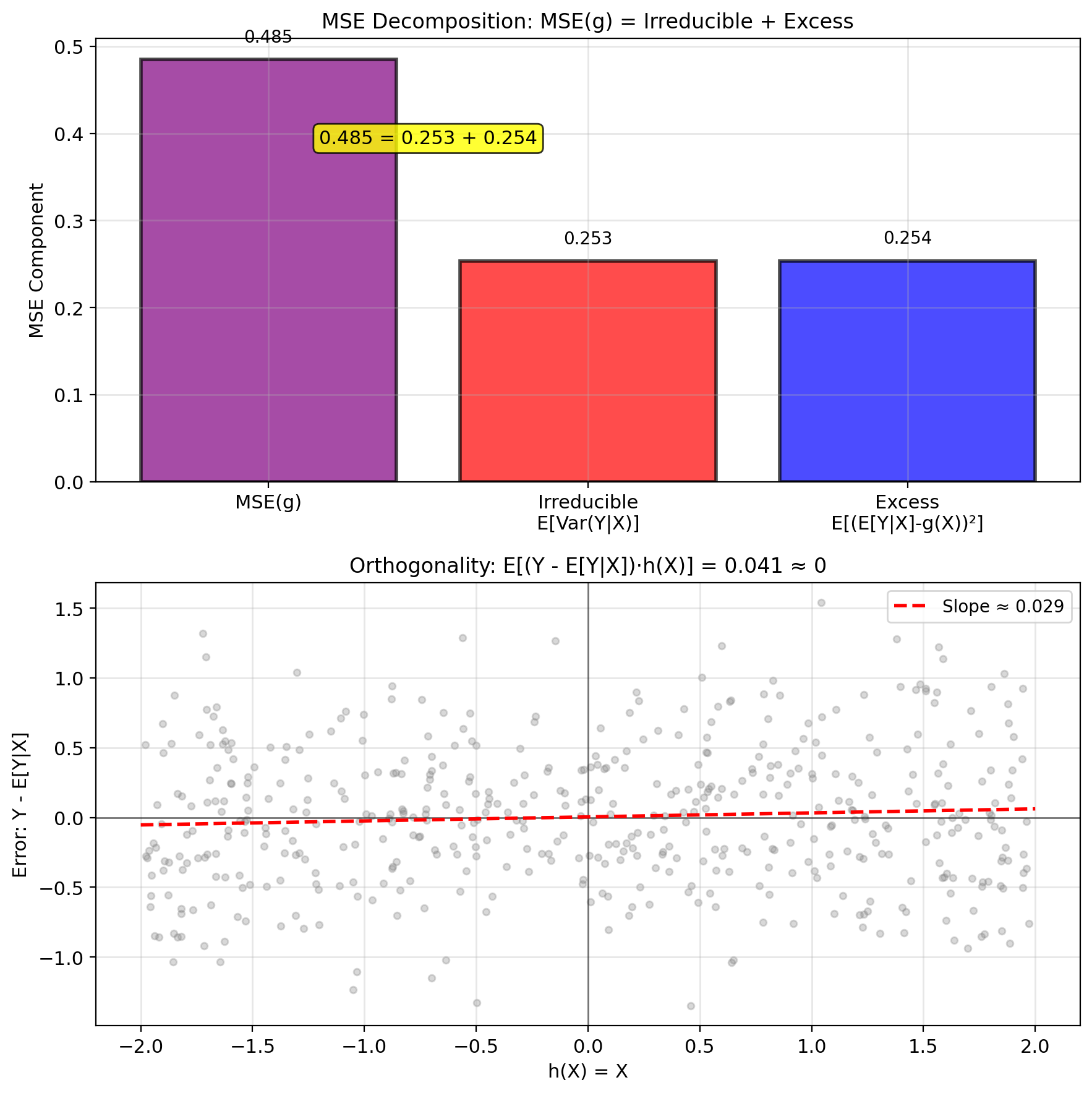

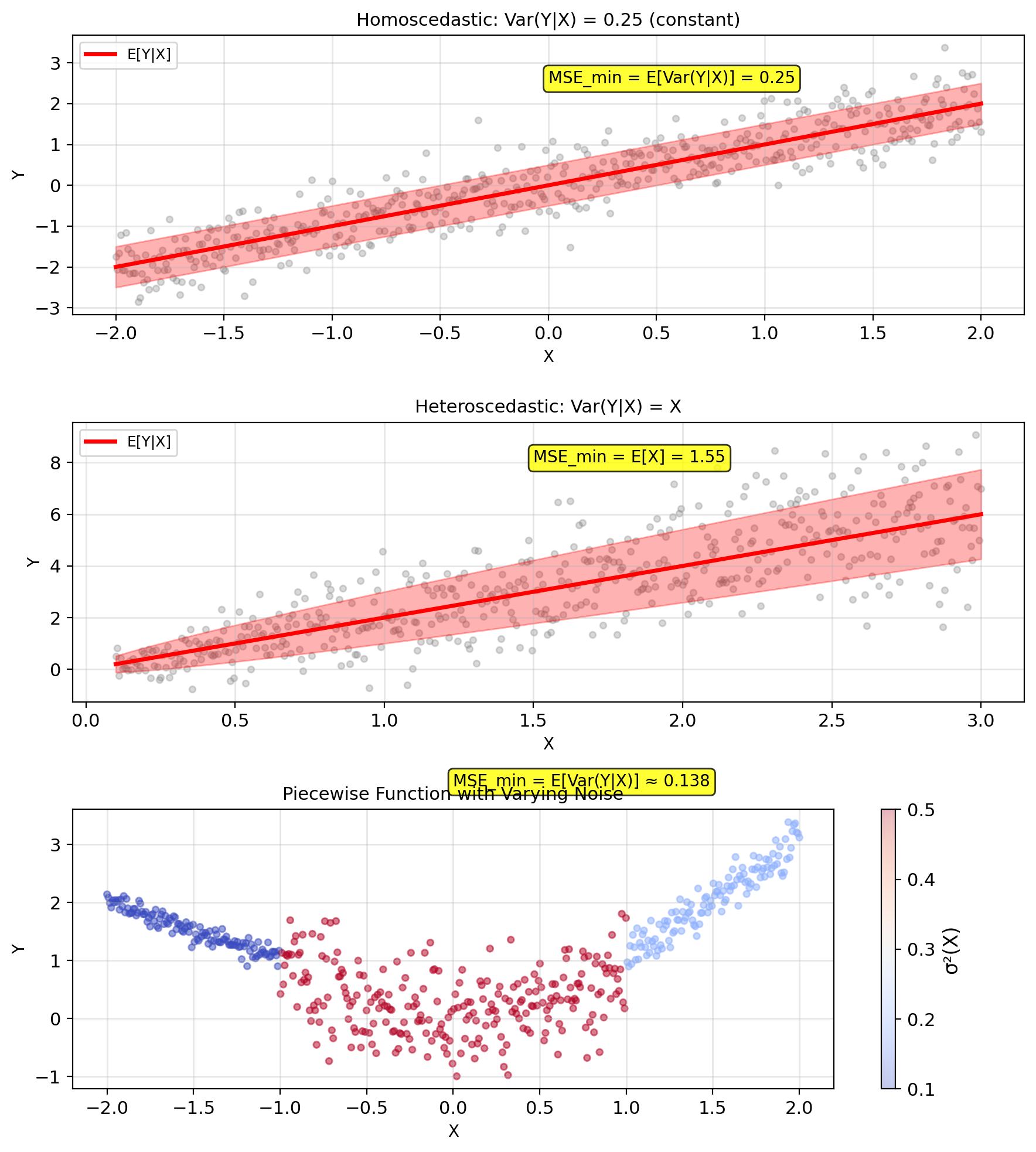

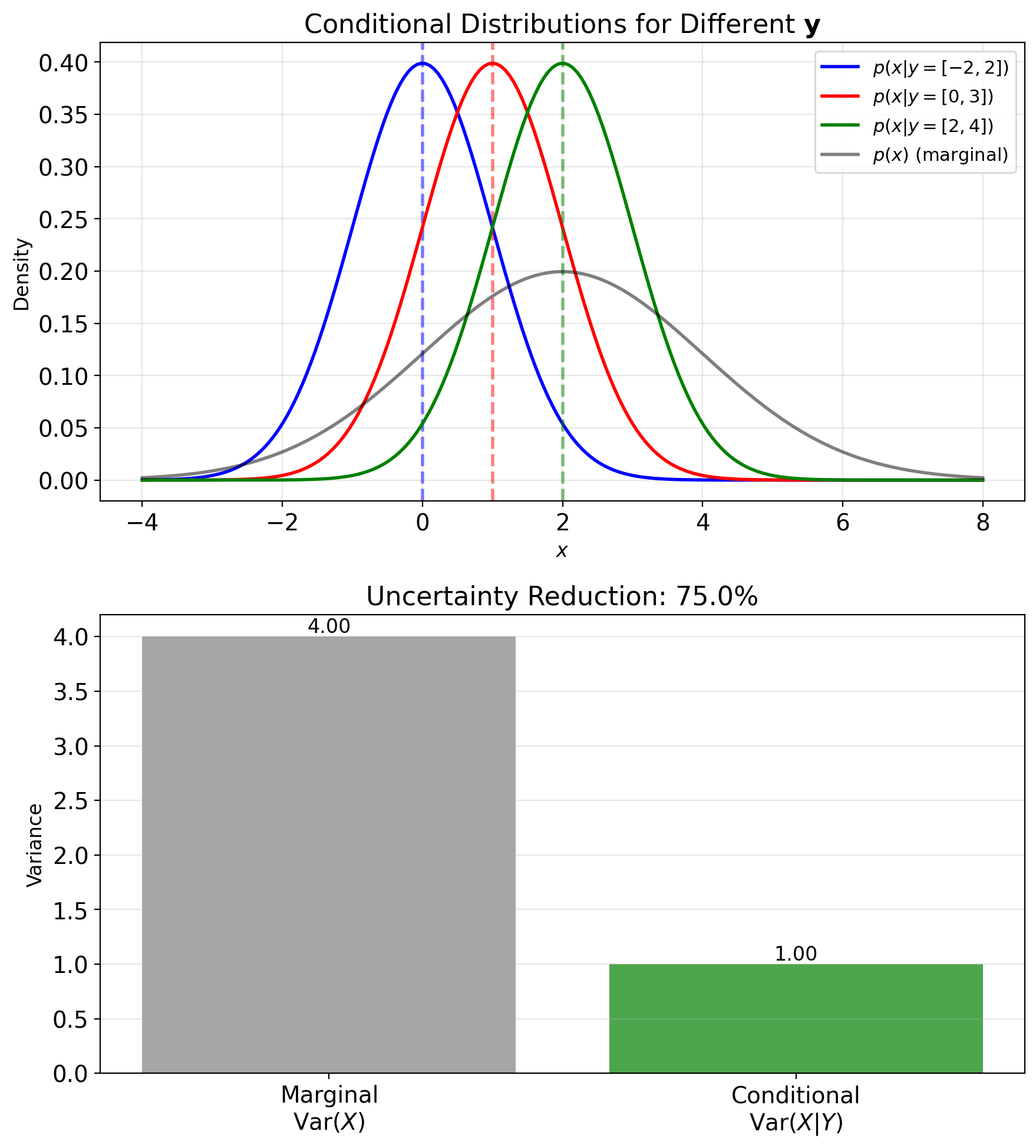

Var(Y|X) Is Irreducible Uncertainty

Definition: \[\text{Var}(Y|X) = \mathbb{E}[(Y - \mathbb{E}[Y|X])^2 | X]\]

Computing formula: \[\text{Var}(Y|X) = \mathbb{E}[Y^2|X] - (\mathbb{E}[Y|X])^2\]

Measures remaining uncertainty after observing \(X\)

Law of Total Variance: \[\text{Var}(Y) = \mathbb{E}[\text{Var}(Y|X)] + \text{Var}(\mathbb{E}[Y|X])\]

- First term: Average conditional variance (irreducible)

- Second term: Variance of conditional means (explained)

Interpretation: \[\text{Total uncertainty} = \text{Unexplained} + \text{Explained by } X\]

Minimum MSE: \[\text{MSE}_{\text{min}} = \mathbb{E}[(Y - \mathbb{E}[Y|X])^2] = \mathbb{E}[\text{Var}(Y|X)]\]

Cannot do better than conditional variance!

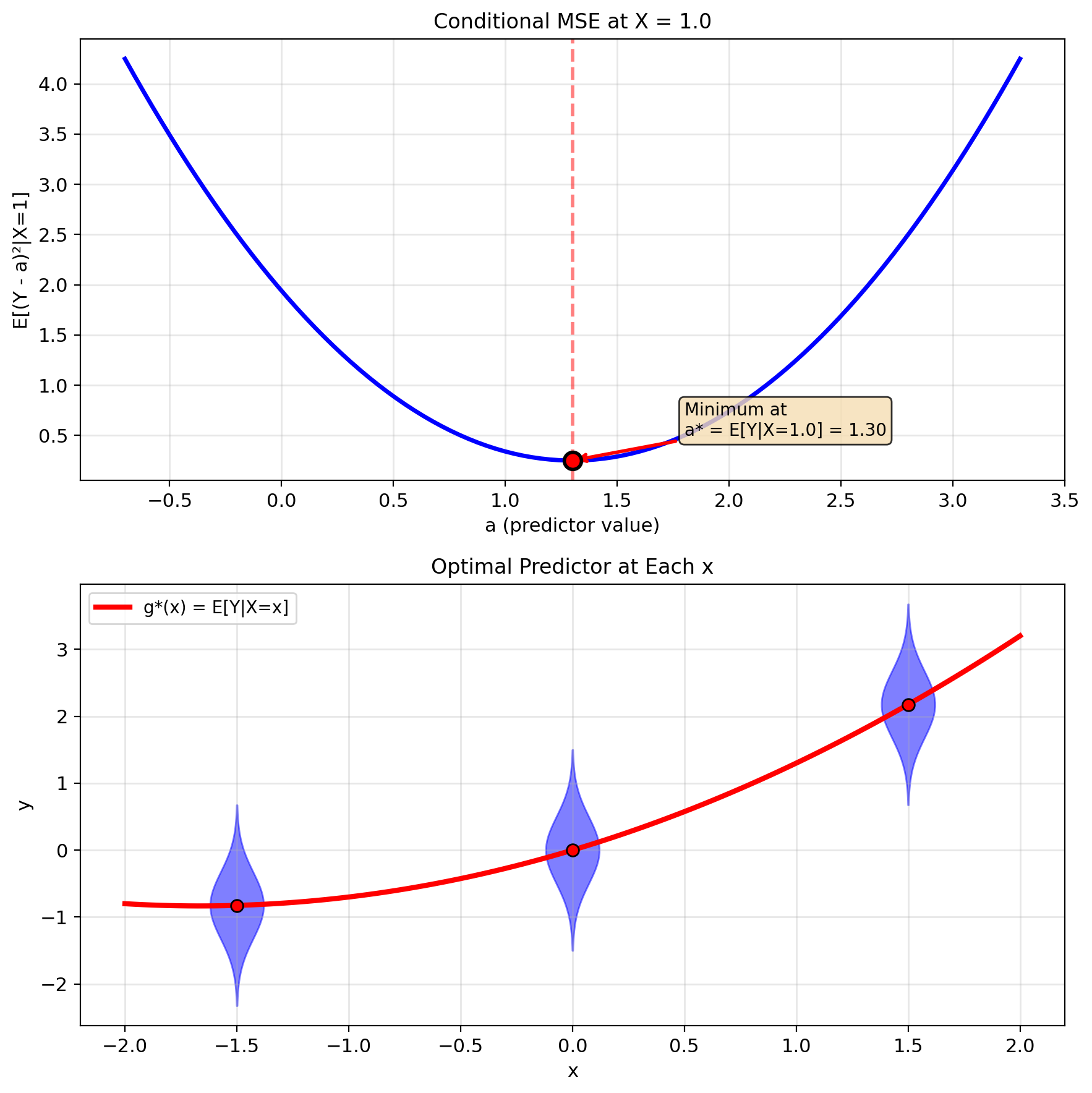

E[Y|X] Minimizes MSE Over All Functions

(prove next):

Among all functions \(g: \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\): \[\mathbb{E}[Y|X] = \arg\min_{g} \mathbb{E}[(Y - g(X))^2]\]

Achieving minimum MSE: \[\text{MSE}_{\text{min}} = \mathbb{E}[\text{Var}(Y|X)]\]

i.e., cannot beat the average conditional variance.

Why conditional expectation?

For fixed \(X = x\), minimizing \(\mathbb{E}[(Y - c)^2|X=x]\) over constants \(c\) yields: \[c^* = \mathbb{E}[Y|X=x]\]

Do this for each \(x\) → optimal function is \(g(x) = \mathbb{E}[Y|X=x]\)

Computational reality:

- Need \(p(y|x)\) to compute \(\mathbb{E}[Y|X=x] = \int y p(y|x) dy\)

- Gaussian: Closed form (linear!)

- General: Often intractable

Constraints simplify the problem.

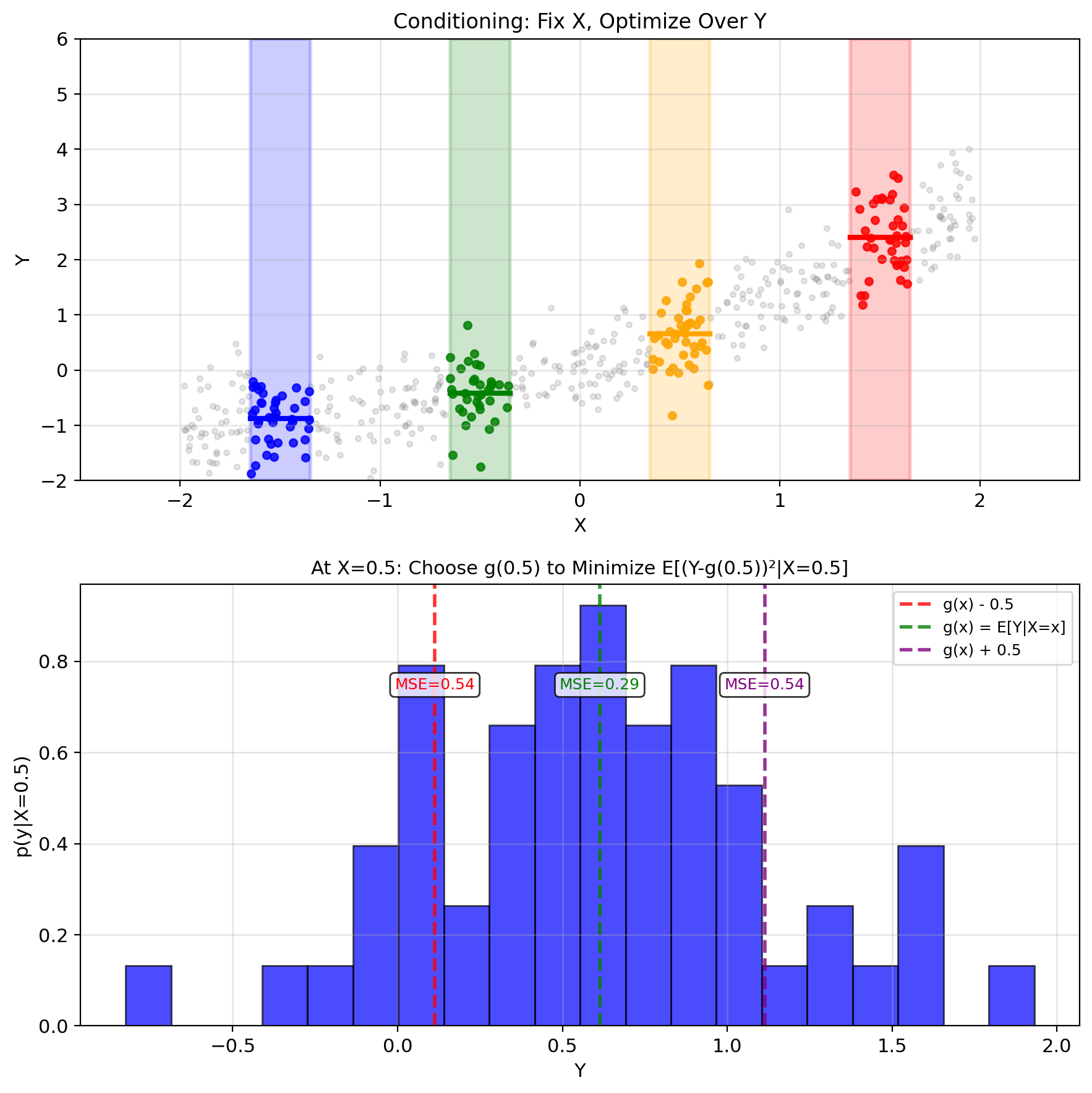

The Optimal Predictor Is E[Y|X]

MMSE Searches All Measurable Functions

Goal: Find the best predictor of \(Y\) given \(X\)

Function space: \[\mathcal{G} = \{g: \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R} \text{ measurable}\}\]

Optimization problem: \[\min_{g \in \mathcal{G}} \text{MSE}(g) = \min_{g \in \mathcal{G}} \mathbb{E}[(Y - g(X))^2]\]

Infinite-dimensional optimization

- Search over all possible functions

- No parametric form assumed

- Need functional analysis tools

Strategy: Decompose the problem by conditioning on \(X\)

- Fix \(X = x\), solve pointwise optimization

- Combine solutions for all \(x\)

- Verify global optimality

Conditioning Decomposes MSE into Subproblems

Decomposition: \[\text{MSE}(g) = \mathbb{E}[(Y - g(X))^2] = \mathbb{E}[\mathbb{E}[(Y - g(X))^2|X]]\]

Why this helps:

- Outside expectation: Average over \(X\)

- Inside expectation: For each fixed \(X = x\)

When \(X = x\) is fixed:

- \(g(X) = g(x)\) is just a number

- \(Y|X=x\) has distribution \(p(y|x)\)

- We minimize: \(\mathbb{E}[(Y - g(x))^2|X=x]\)

This transforms the problem:

- From: Find optimal function \(g\)

- To: For each \(x\), find optimal constant \(g(x)\)

Solution approach:

- Fix \(x\), find best constant predictor

- This gives us \(g^*(x)\) for each \(x\)

- The function \(g^*\) is our MMSE estimator

First-Order Condition Yields E[Y|X]

Step 1: Express MSE using conditional expectation \[\text{MSE}(g) = \mathbb{E}[(Y - g(X))^2]\] \[= \mathbb{E}[\mathbb{E}[(Y - g(X))^2|X]]\]

Step 2: For fixed \(X = x\), \(g(X) = g(x)\) is a constant \[\mathbb{E}[(Y - g(x))^2|X=x] = \mathbb{E}[(Y - a)^2|X=x]\] where \(a = g(x)\)

Step 3: Minimize over \(a\) \[\frac{d}{da}\mathbb{E}[(Y - a)^2|X=x] = 0\] \[-2\mathbb{E}[(Y - a)|X=x] = 0\] \[\mathbb{E}[Y|X=x] - a = 0\]

Solution: \(a^* = \mathbb{E}[Y|X=x]\)

Step 4: Since this holds for all \(x\): \[g^*(x) = \mathbb{E}[Y|X=x]\]

Therefore: \[\boxed{\hat{Y}_{\text{MMSE}} = \mathbb{E}[Y|X]}\]

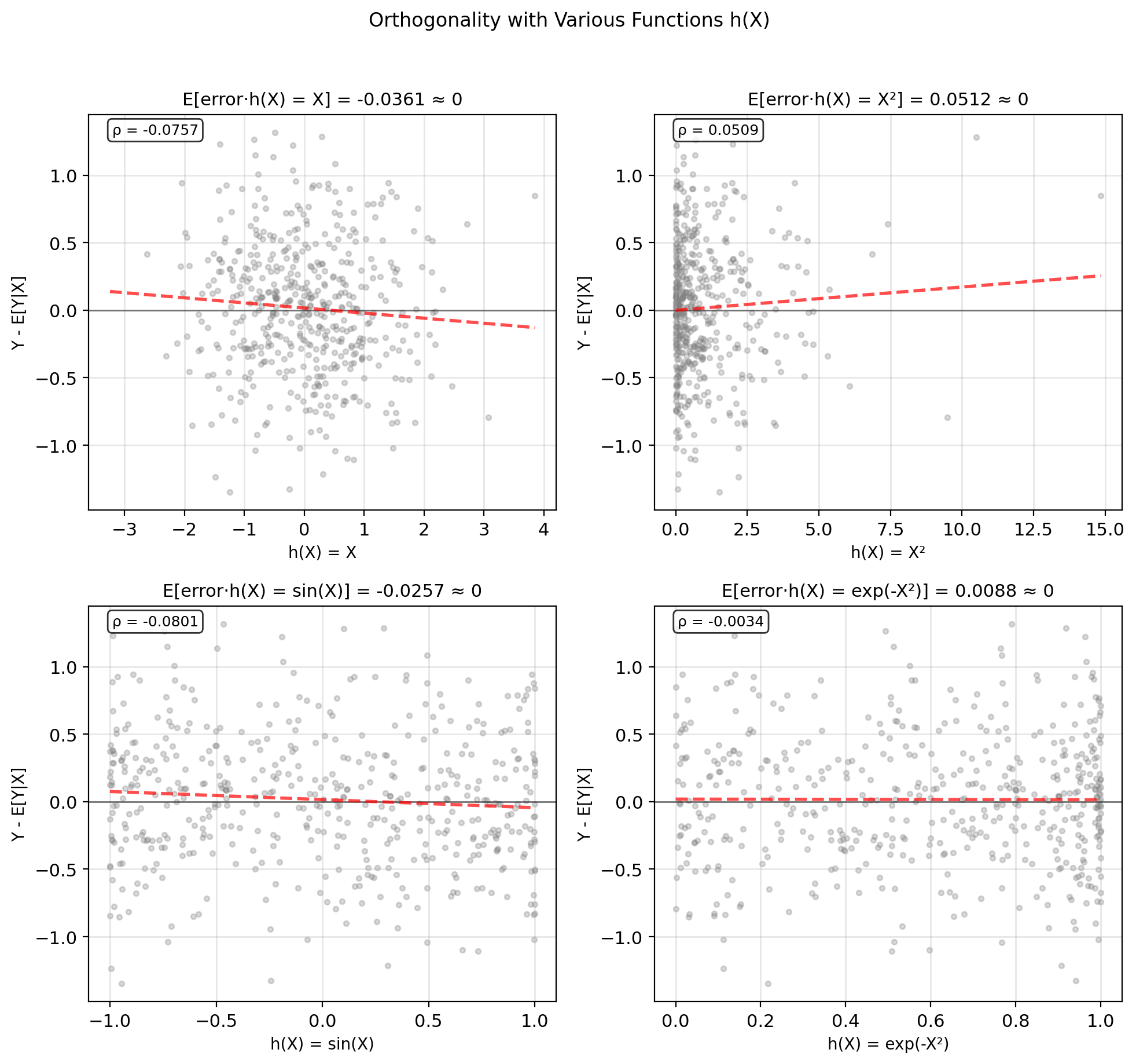

Optimal Error Is Uncorrelated with h(X)

Orthogonality principle: Optimal error orthogonal to any function of \(X\): \[\mathbb{E}[(Y - \mathbb{E}[Y|X])h(X)] = 0\] for any measurable \(h\).

Uniqueness: Only one function satisfies this → unique MMSE

Optimality test: If \(\mathbb{E}[\epsilon \cdot h(X)] \neq 0\), can reduce MSE by adjusting estimate in direction of \(h(X)\)

Computational foundation:

- Linear case → normal equations

- Adaptive filters → orthogonalize error

- Kalman filter → innovation orthogonality

Geometric meaning: MMSE = projection in Hilbert space

Proof: \(\mathbb{E}[(Y - \mathbb{E}[Y|X])|X] = 0\) by definition, multiplying by \(h(X)\) preserves this.

Cannot extract more information from \(X\)

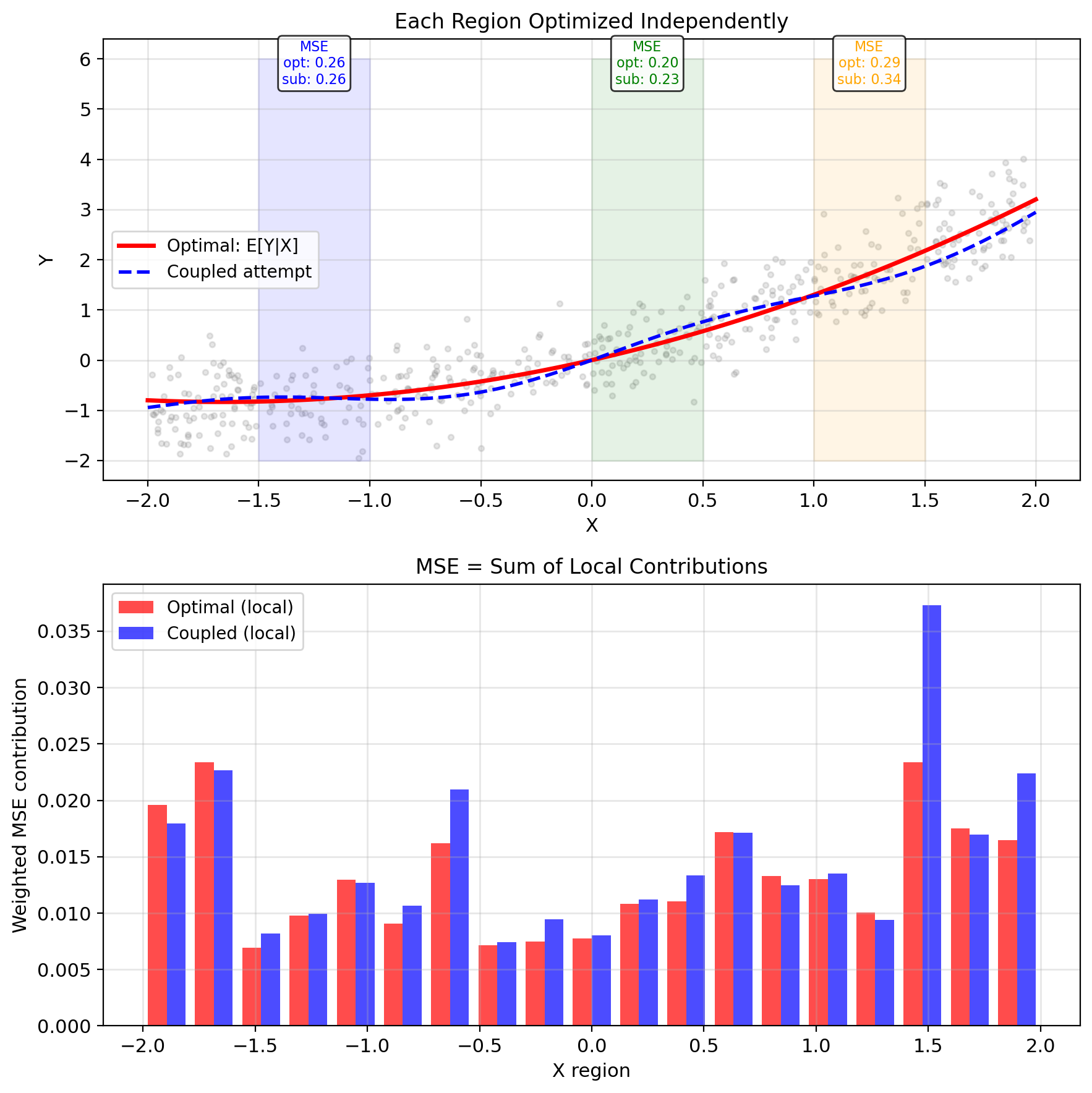

Pointwise Optimality Implies Global Optimality

We solved pointwise: For each \(x\), found \(g^*(x) = \mathbb{E}[Y|X=x]\)

Question: Is this globally optimal over all functions?

Two concerns:

- We optimized separately at each \(x\)

- Maybe coupling across different \(x\) values helps?

Key fact: MSE decomposes additively \[\text{MSE}(g) = \int \mathbb{E}[(Y - g(x))^2|X=x] p(x) dx\]

Each term \(\mathbb{E}[(Y - g(x))^2|X=x]\) depends only on \(g(x)\), not on \(g(x')\) for \(x' \neq x\).

Therefore:

- Minimizing each term separately minimizes the sum

- No coupling can improve the solution

- Pointwise optimization = Global optimization

Idea: Prediction at \(x\) doesn’t help prediction at \(x'\)

Suboptimal Predictors Add Excess MSE

Claim: No function can beat \(\mathbb{E}[Y|X]\)

Proof: For any function \(g\): \[\text{MSE}(g) = \mathbb{E}[(Y - g(X))^2]\]

Add and subtract \(\mathbb{E}[Y|X]\): \[= \mathbb{E}[(Y - \mathbb{E}[Y|X] + \mathbb{E}[Y|X] - g(X))^2]\]

Expand the square: \[= \mathbb{E}[(Y - \mathbb{E}[Y|X])^2] + \mathbb{E}[(\mathbb{E}[Y|X] - g(X))^2]\] \[+ 2\mathbb{E}[(Y - \mathbb{E}[Y|X])(\mathbb{E}[Y|X] - g(X))]\]

Key: The cross term is zero! \[\mathbb{E}[(Y - \mathbb{E}[Y|X])(\mathbb{E}[Y|X] - g(X))] = 0\]

Because \(\mathbb{E}[Y|X] - g(X)\) is a function of \(X\) and: \[\mathbb{E}[(Y - \mathbb{E}[Y|X])h(X)] = 0\] for any \(h(X)\) (orthogonality).

Therefore: \[\text{MSE}(g) = \text{MSE}_{\min} + \mathbb{E}[(\mathbb{E}[Y|X] - g(X))^2] \geq \text{MSE}_{\min}\]

Theorem: E[Y|X] Is the MMSE Estimator

Theorem: Let \((X, Y)\) have \(\mathbb{E}[Y^2] < \infty\). Then: \[\boxed{\hat{Y}_{\text{MMSE}} = \mathbb{E}[Y|X] = \arg\min_{g} \mathbb{E}[(Y - g(X))^2]}\]

Proof:

1. Decompose by conditioning: \[\text{MSE}(g) = \mathbb{E}[(Y - g(X))^2] = \mathbb{E}\bigl[\mathbb{E}[(Y - g(X))^2 | X]\bigr]\]

2. Solve pointwise: For fixed \(X = x\), minimize over constant \(c\): \[\frac{d}{dc}\mathbb{E}[(Y - c)^2 | X = x] = -2\mathbb{E}[Y - c | X = x] = 0\] \[\implies c^* = \mathbb{E}[Y | X = x]\]

3. Global optimality: MSE decomposes additively over \(x\). Each term minimized separately \(\implies\) sum minimized.

4. Orthogonality: Error \(\varepsilon = Y - \mathbb{E}[Y|X]\) satisfies: \[\mathbb{E}[\varepsilon \cdot h(X)] = 0 \quad \text{for all } h\]

This uniquely characterizes the solution.

5. Minimum MSE: \[\boxed{\text{MSE}_{\min} = \mathbb{E}[\text{Var}(Y|X)]}\]

MSE_min = E[Var(Y|X)]

Minimum achievable MSE: \[\text{MSE}_{\min} = \mathbb{E}[(Y - \mathbb{E}[Y|X])^2]\]

Result: \[\boxed{\text{MSE}_{\min} = \mathbb{E}[\text{Var}(Y|X)]}\]

Proof: \[\text{MSE}_{\min} = \mathbb{E}[(Y - \mathbb{E}[Y|X])^2]\] \[= \mathbb{E}[\mathbb{E}[(Y - \mathbb{E}[Y|X])^2|X]]\]

For fixed \(X = x\): \[\mathbb{E}[(Y - \mathbb{E}[Y|X=x])^2|X=x] = \text{Var}(Y|X=x)\]

Therefore: \[\text{MSE}_{\min} = \mathbb{E}[\text{Var}(Y|X)]\]

- Cannot eliminate conditional variance

- Irreducible uncertainty

- Fundamental limit of prediction

Special cases:

- \(X\) and \(Y\) independent: \(\text{MSE}_{\min} = \text{Var}(Y)\)

- \(Y = f(X)\) deterministic: \(\text{MSE}_{\min} = 0\)

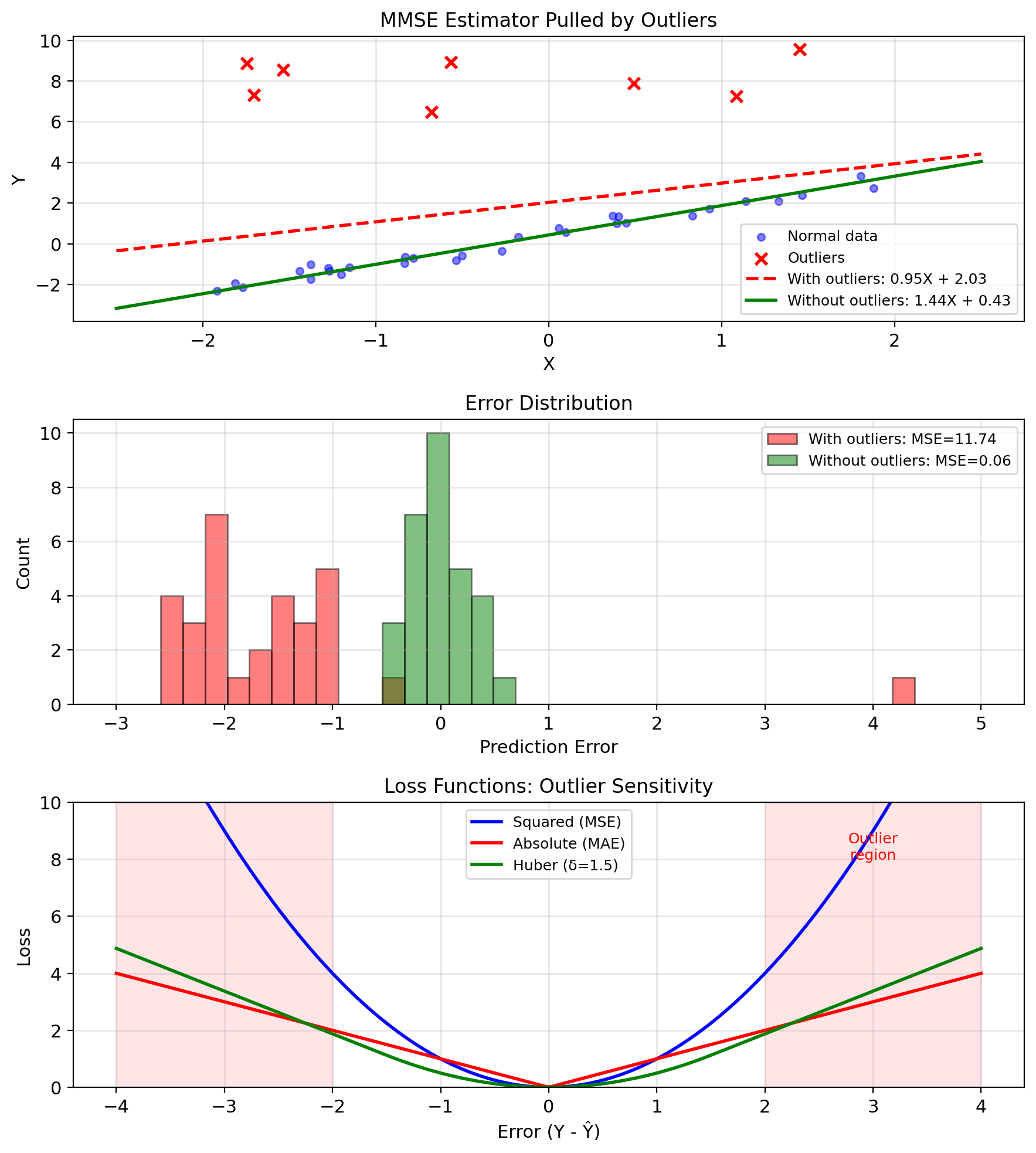

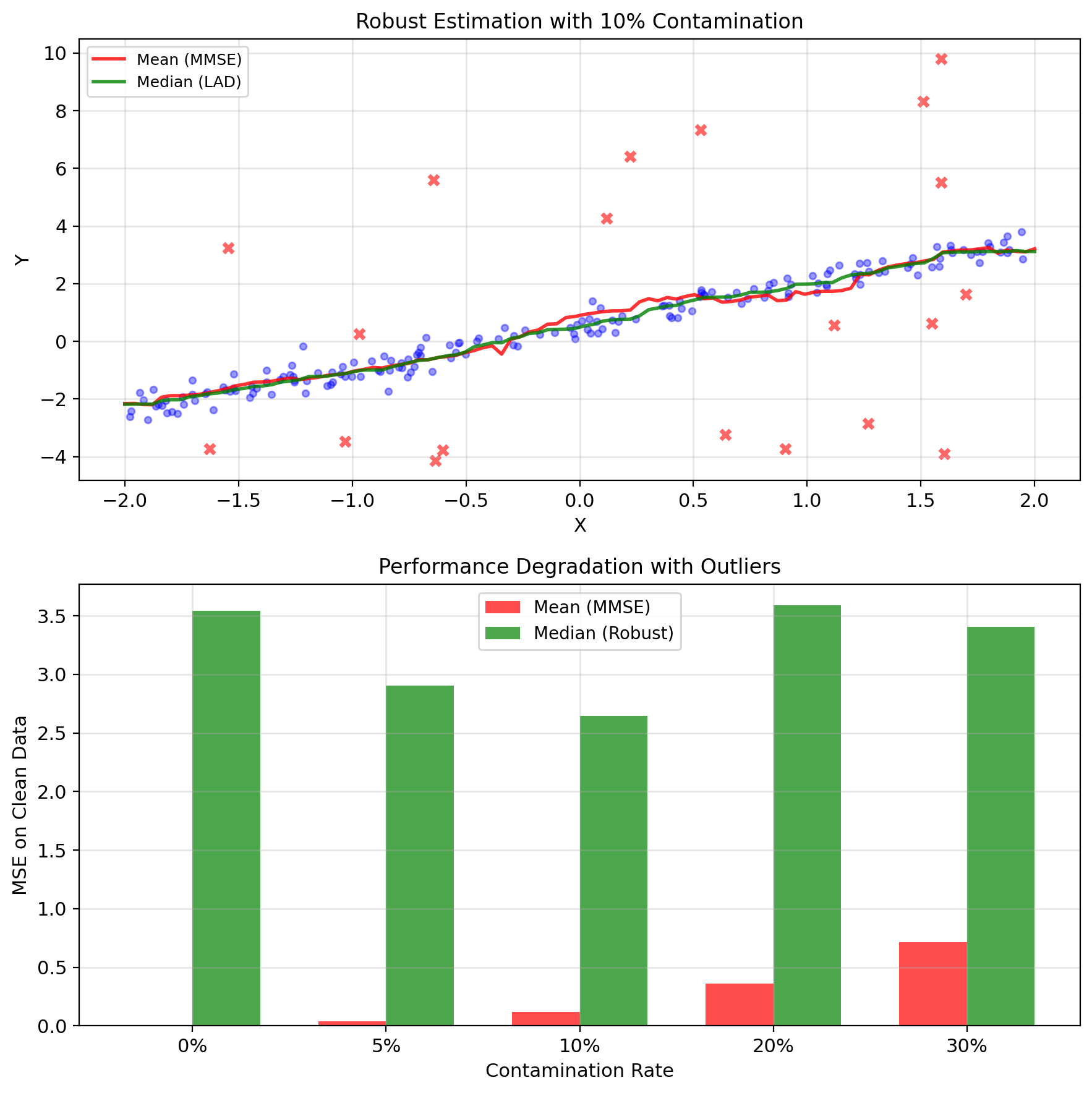

Squared Error Makes MMSE Outlier-Sensitive

Squared error is sensitive to outliers

Single outlier can dominate MSE: \[\text{MSE} = \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n (y_i - \hat{y}_i)^2\]

If \(y_k\) is outlier: \((y_k - \hat{y}_k)^2 \gg (y_i - \hat{y}_i)^2\) for \(i \neq k\)

Effect on MMSE:

- \(\mathbb{E}[Y|X]\) gets pulled toward outliers

- Large increase in MSE

- Solution may not represent majority of data

Example: Sensor failure

- 99 readings: \(Y \approx X + \varepsilon\), \(\varepsilon \sim \mathcal{N}(0, 0.1^2)\)

- 1 reading: \(Y = 100\) (sensor spike)

MMSE tries to accommodate the outlier, degrading performance for typical cases.

Alternative loss functions:

- Absolute error: \(|Y - \hat{Y}|\) (median)

- Huber loss: Quadratic for small errors, linear for large

- Trimmed MSE: Ignore largest errors

Median Regression Resists Outliers

When outliers are present:

Median regression (LAD): \[\min_g \mathbb{E}[|Y - g(X)|]\] Solution: \(g^*(x) = \text{median}(Y|X=x)\)

Huber regression: \[\min_g \mathbb{E}[\ell_\delta(Y - g(X))]\] where \(\ell_\delta(e) = \begin{cases} \frac{1}{2}e^2 & |e| \leq \delta \\ \delta|e| - \frac{\delta^2}{2} & |e| > \delta \end{cases}\)

Trimmed mean: Remove top/bottom α% before computing \(\mathbb{E}[Y|X]\)

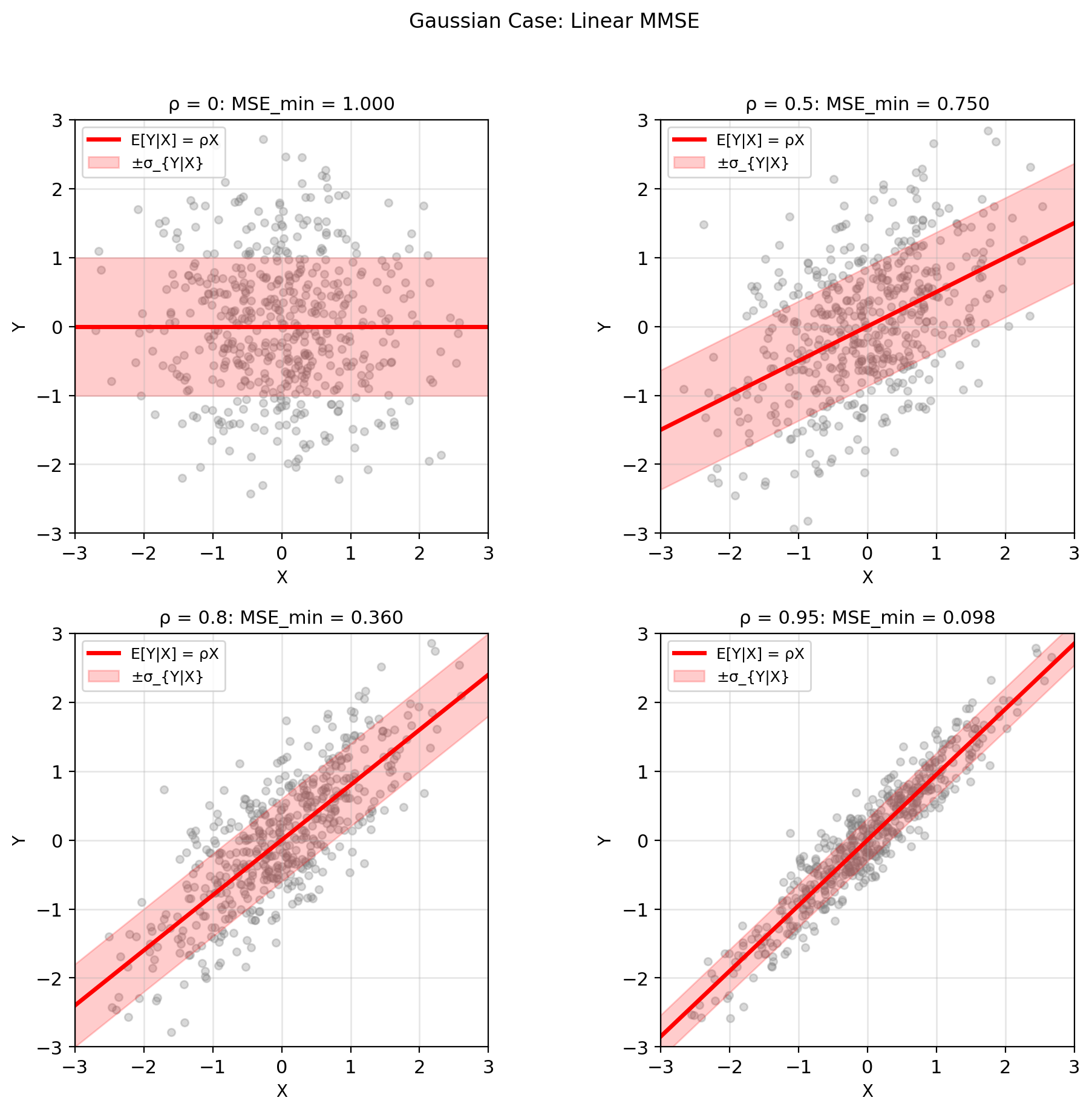

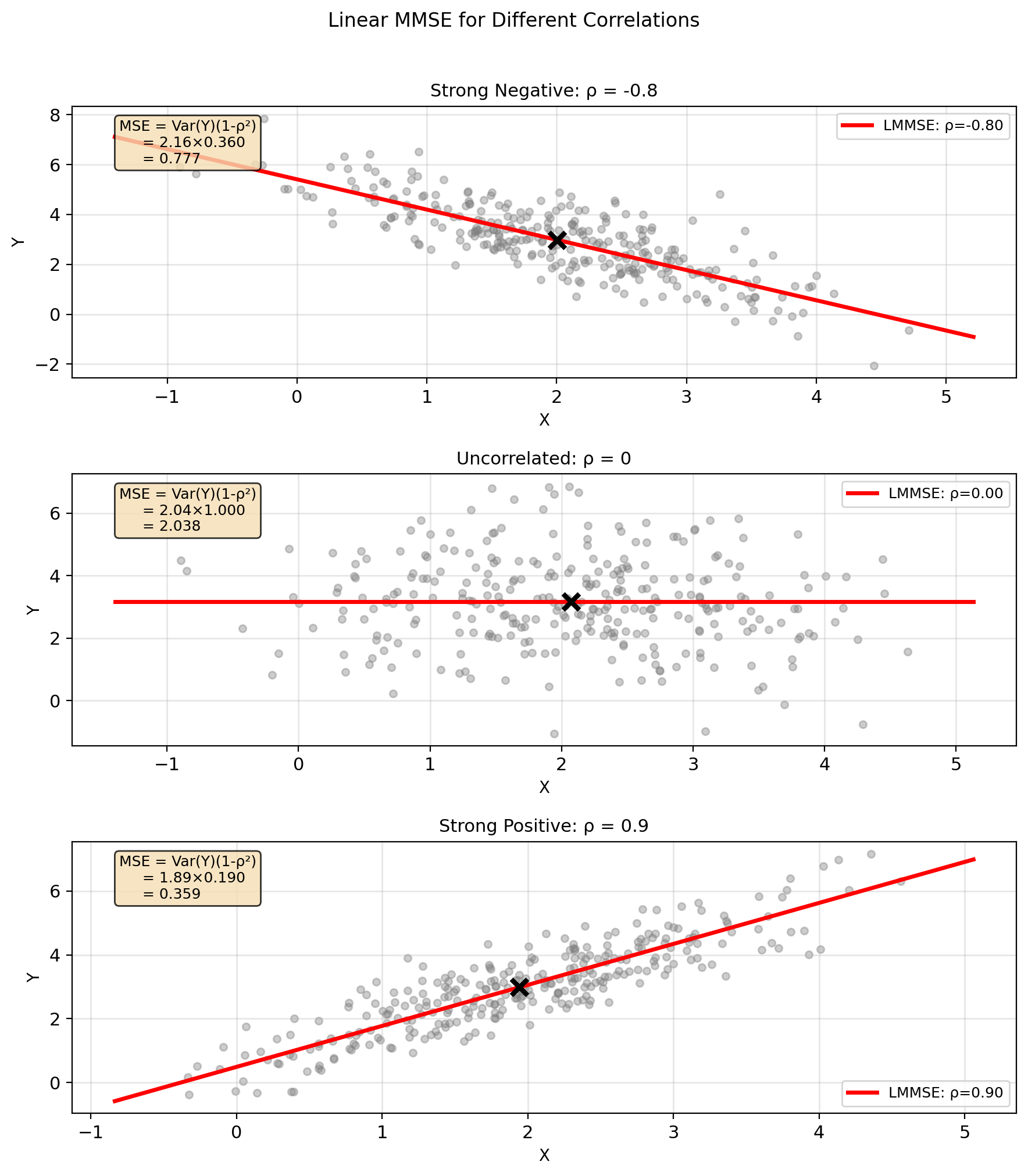

Gaussian: MSE = σ²(1 - ρ²)

Joint Gaussian: \((X, Y) \sim \mathcal{N}(\mu, K)\)

\[K = \begin{bmatrix} \sigma_X^2 & \rho\sigma_X\sigma_Y \\ \rho\sigma_X\sigma_Y & \sigma_Y^2 \end{bmatrix}\]

MMSE estimator: \[\hat{Y}_{\text{MMSE}} = \mathbb{E}[Y|X] = \mu_Y + \rho\frac{\sigma_Y}{\sigma_X}(X - \mu_X)\]

Key property: Linear in \(X\)!

Minimum MSE: \[\text{MSE}_{\min} = \mathbb{E}[\text{Var}(Y|X)] = \sigma_Y^2(1 - \rho^2)\]

Observations:

- \(\rho = 0\): MSE\(_{\min}\) = \(\sigma_Y^2\) (no improvement)

- \(|\rho| = 1\): MSE\(_{\min}\) = 0 (perfect prediction)

- Linear MMSE = Unrestricted MMSE

Why linear? Gaussian conditional \(Y|X\) has:

- Mean linear in \(x\)

- Variance independent of \(x\)

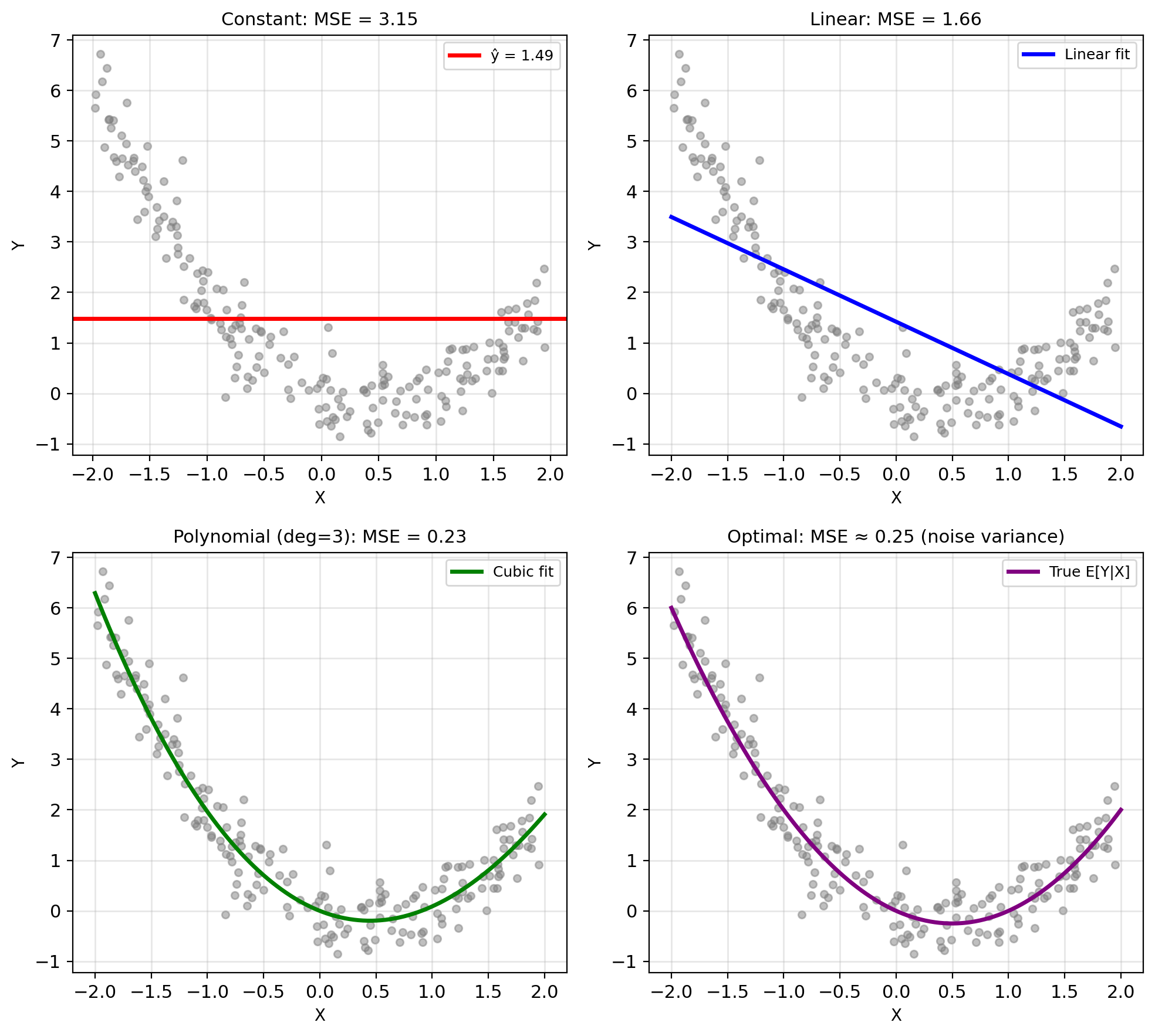

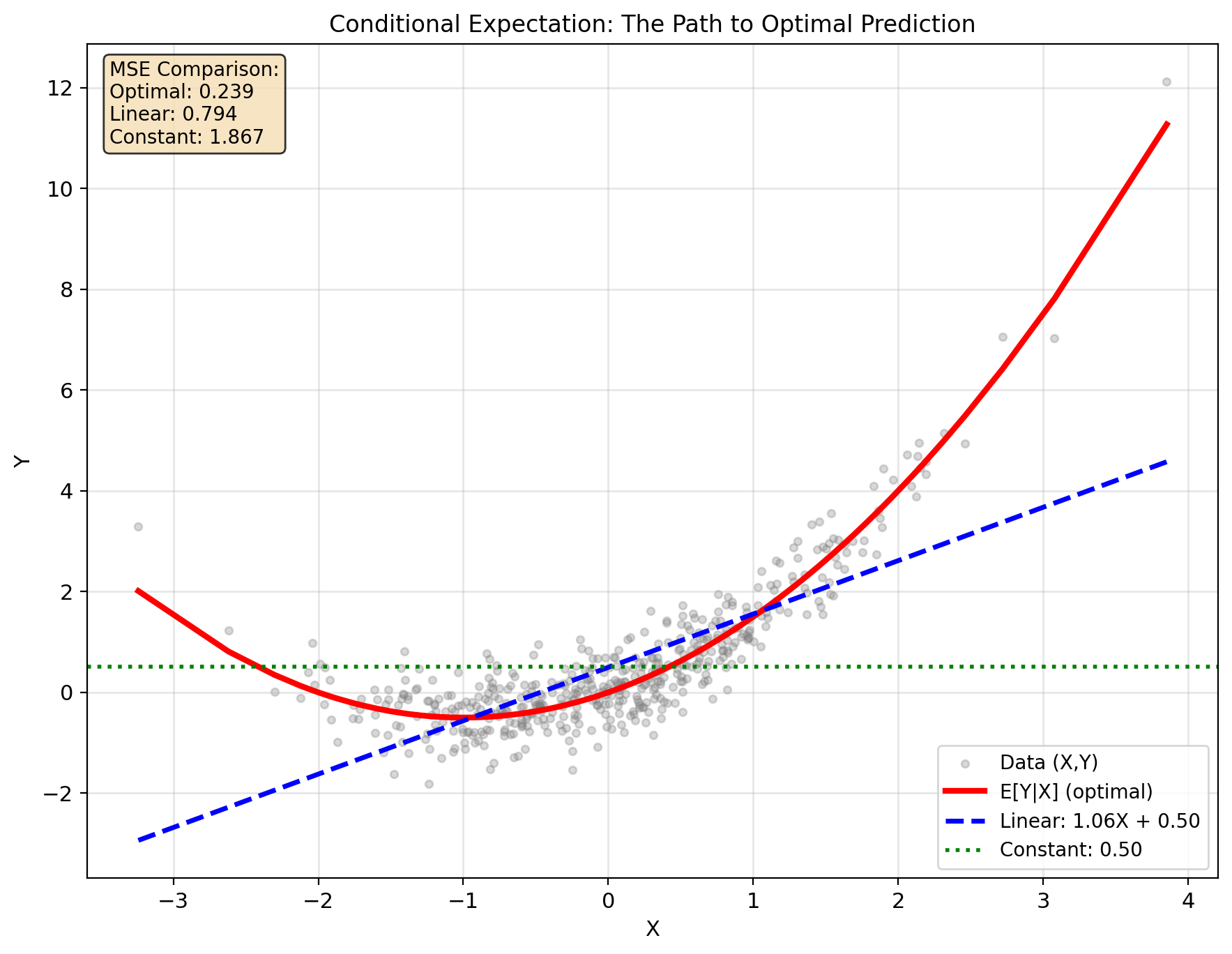

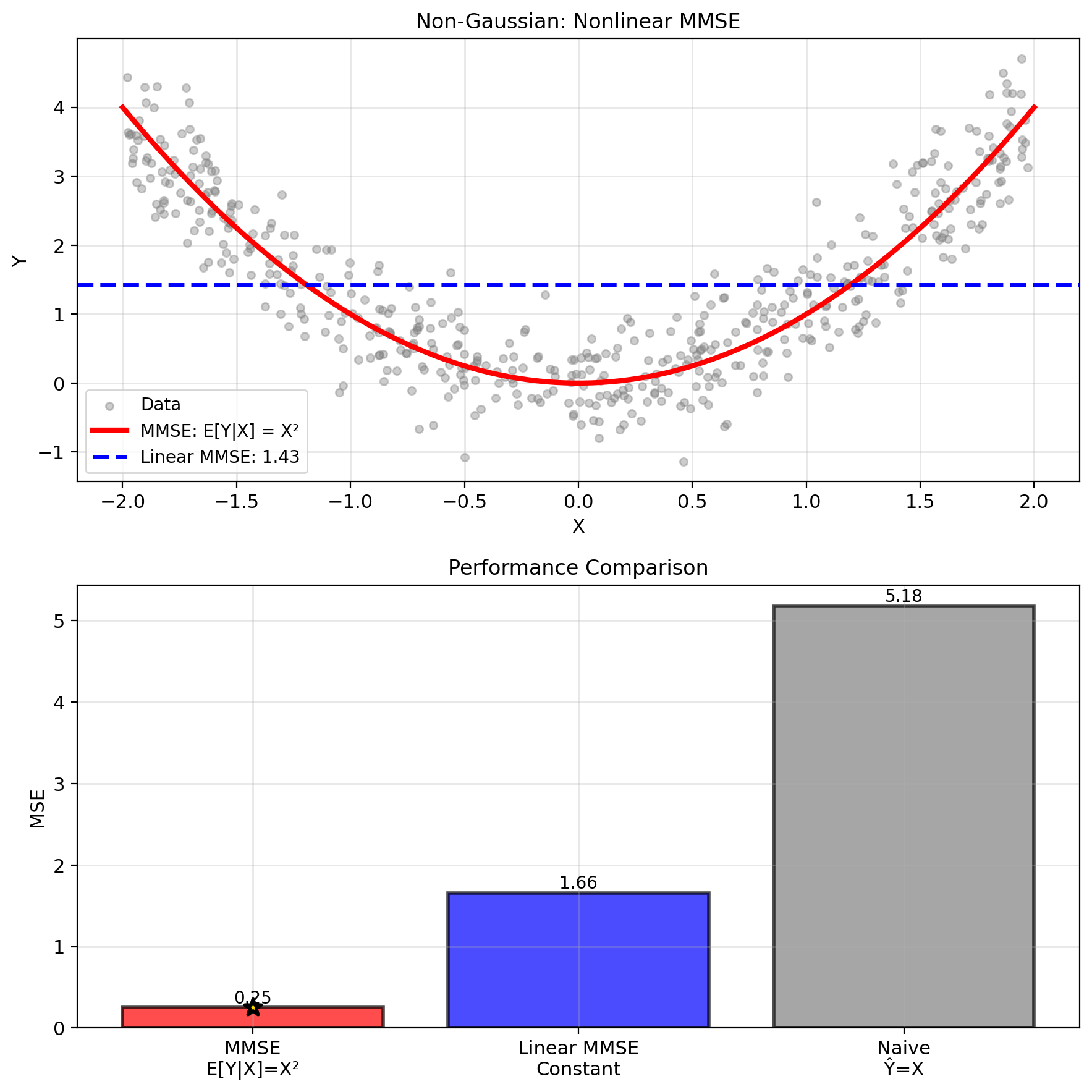

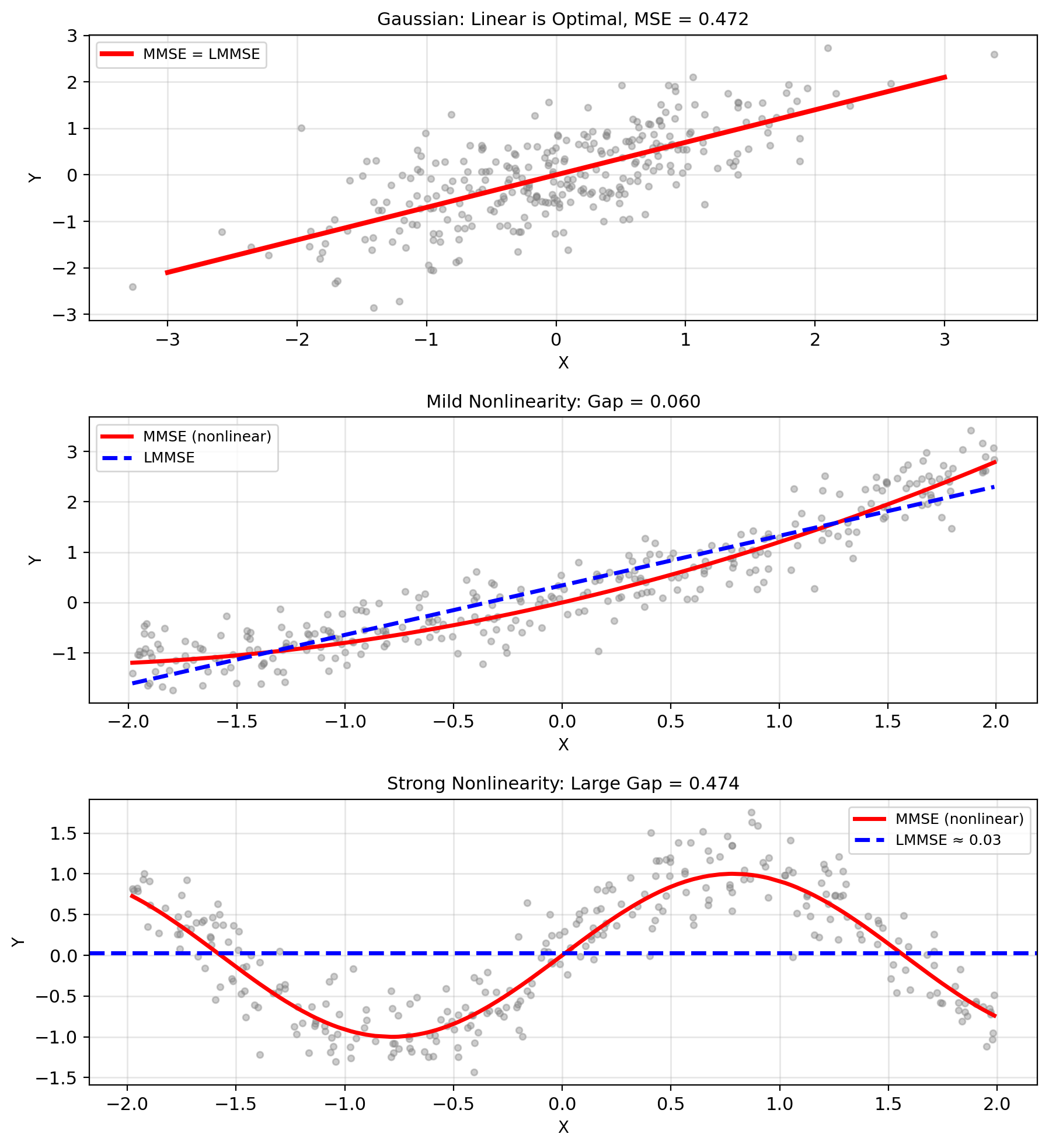

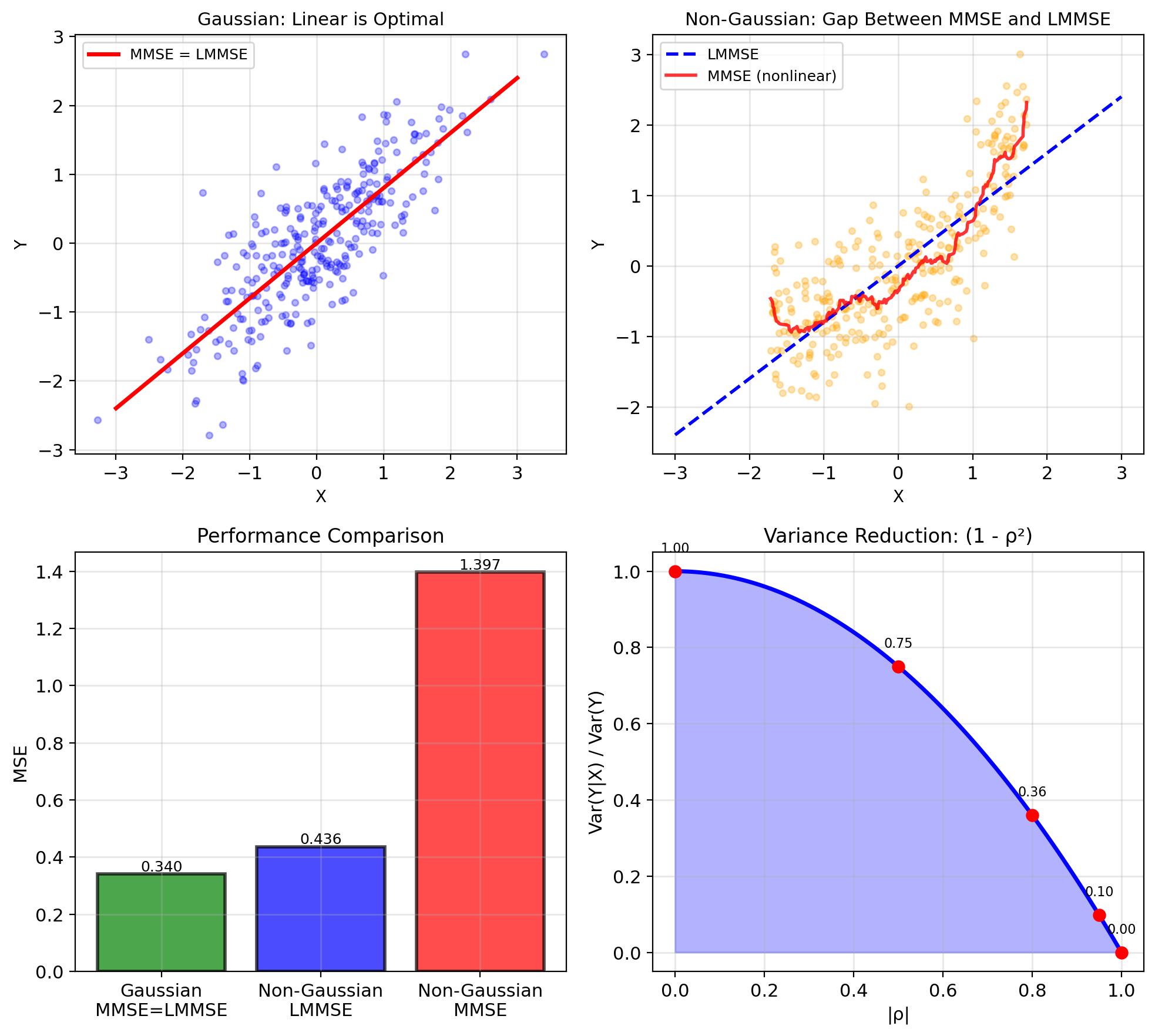

Nonlinear E[Y|X] Creates a Performance Gap

Uniform-Quadratic example:

- \(X \sim \text{Uniform}(-2, 2)\)

- \(Y = X^2 + N\), \(N \sim \mathcal{N}(0, 0.5^2)\)

MMSE estimator: \[\hat{Y}_{\text{MMSE}} = \mathbb{E}[Y|X] = X^2\]

NOTE: Nonlinear in \(X\)

Linear MMSE (suboptimal): \[\hat{Y}_{\text{linear}} = \mathbb{E}[Y] + \frac{\text{Cov}(X,Y)}{\text{Var}(X)}(X - \mathbb{E}[X])\]

Since \(\mathbb{E}[X] = 0\) and \(\text{Cov}(X,Y) = \mathbb{E}[X^3] = 0\): \[\hat{Y}_{\text{linear}} = \mathbb{E}[Y] = \mathbb{E}[X^2] = \frac{4}{3}\]

Performance gap:

- MSE\(_{\text{MMSE}}\) = \(\sigma_N^2\) = 0.25

- MSE\(_{\text{linear}}\) = Var(\(X^2\)) + \(\sigma_N^2\) ≈ 2.17

Linear loses significant performance when true relationship is nonlinear!

Geometric Foundations for Linear Estimation

Inner Products Measure Alignment

Definition: For vectors \(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y} \in \mathbb{R}^n\) \[\langle \mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y} \rangle = \mathbf{x}^T\mathbf{y} = \sum_{i=1}^n x_i y_i\]

Geometric interpretation: \[\langle \mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y} \rangle = \|\mathbf{x}\| \|\mathbf{y}\| \cos\theta\]

where \(\theta\) is the angle between vectors.

Special cases:

- \(\theta = 0°\): \(\langle \mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y} \rangle = \|\mathbf{x}\|\|\mathbf{y}\|\) (aligned)

- \(\theta = 90°\): \(\langle \mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y} \rangle = 0\) (orthogonal)

- \(\theta = 180°\): \(\langle \mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y} \rangle = -\|\mathbf{x}\|\|\mathbf{y}\|\) (opposed)

Norm from inner product: \[\|\mathbf{x}\| = \sqrt{\langle \mathbf{x}, \mathbf{x} \rangle} = \sqrt{\sum_i x_i^2}\]

Projection Finds the Closest Point in a Subspace

Problem: Given \(\mathbf{y}\) and subspace \(\mathcal{S}\), find \(\hat{\mathbf{y}} \in \mathcal{S}\) that minimizes \[\|\mathbf{y} - \hat{\mathbf{y}}\|^2\]

Solution: \(\hat{\mathbf{y}} = \text{Proj}_{\mathcal{S}}(\mathbf{y})\)

Projection onto a line (1D subspace):

Given direction \(\mathbf{u}\) with \(\|\mathbf{u}\| = 1\): \[\hat{\mathbf{y}} = \langle \mathbf{y}, \mathbf{u} \rangle \mathbf{u}\]

Projection onto span of \(\{\mathbf{u}_1, \mathbf{u}_2\}\):

If \(\mathbf{u}_1 \perp \mathbf{u}_2\) and both unit vectors: \[\hat{\mathbf{y}} = \langle \mathbf{y}, \mathbf{u}_1 \rangle \mathbf{u}_1 + \langle \mathbf{y}, \mathbf{u}_2 \rangle \mathbf{u}_2\]

The error is what remains: \[\mathbf{e} = \mathbf{y} - \hat{\mathbf{y}}\]

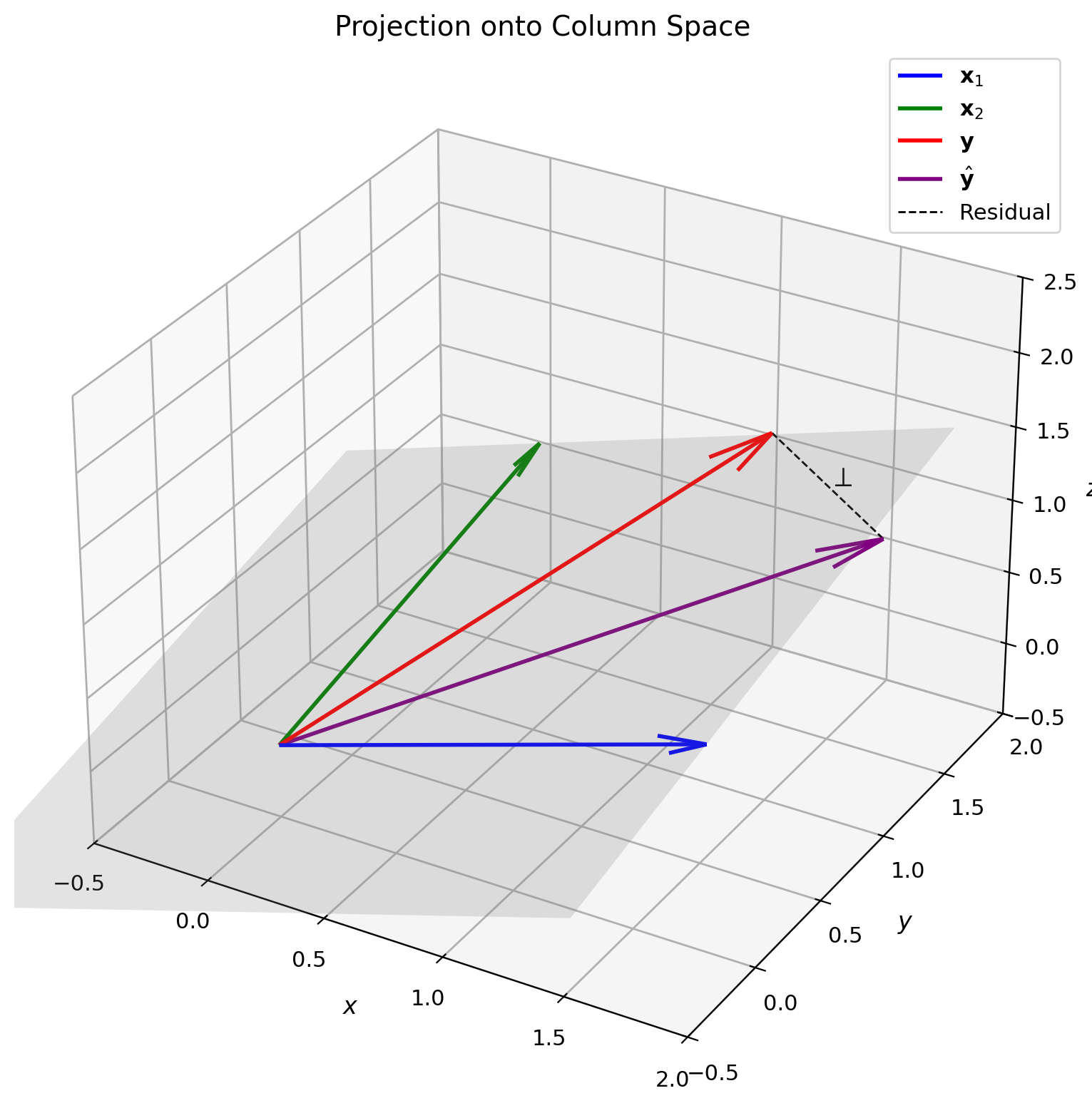

Orthogonality Characterizes the Optimal Projection

Theorem: \(\hat{\mathbf{y}}\) minimizes \(\|\mathbf{y} - \hat{\mathbf{y}}\|^2\) over \(\mathcal{S}\)

if and only if

\[(\mathbf{y} - \hat{\mathbf{y}}) \perp \mathcal{S}\]

Why orthogonality implies optimality:

Suppose error \(\mathbf{e} = \mathbf{y} - \hat{\mathbf{y}}\) is not orthogonal to \(\mathcal{S}\).

Then \(\mathbf{e}\) has a component along \(\mathcal{S}\).

Moving \(\hat{\mathbf{y}}\) in that direction reduces \(\|\mathbf{e}\|\).

Contradiction: \(\hat{\mathbf{y}}\) wasn’t optimal.

Orthogonality conditions:

For \(\mathcal{S} = \text{span}\{\mathbf{v}_1, ..., \mathbf{v}_k\}\): \[\langle \mathbf{y} - \hat{\mathbf{y}}, \mathbf{v}_i \rangle = 0 \quad \text{for } i = 1, ..., k\]

This gives \(k\) equations to solve for \(\hat{\mathbf{y}}\).

Projection onto Higher-Dimensional Subspaces

Matrix formulation:

Let columns of \(X\) span \(\mathcal{S}\): \[X = [\mathbf{x}_1 | \mathbf{x}_2 | \cdots | \mathbf{x}_p]\]

Projection: \(\hat{\mathbf{y}} = X\mathbf{a}\) for some coefficients \(\mathbf{a}\).

Orthogonality conditions: \[X^T(\mathbf{y} - X\mathbf{a}) = \mathbf{0}\]

Normal equations: \[X^TX\mathbf{a} = X^T\mathbf{y}\]

Solution (if \(X^TX\) invertible): \[\mathbf{a} = (X^TX)^{-1}X^T\mathbf{y}\]

Projection matrix: \[P = X(X^TX)^{-1}X^T\] \[\hat{\mathbf{y}} = P\mathbf{y}\]

Properties: \(P^2 = P\), \(P^T = P\)

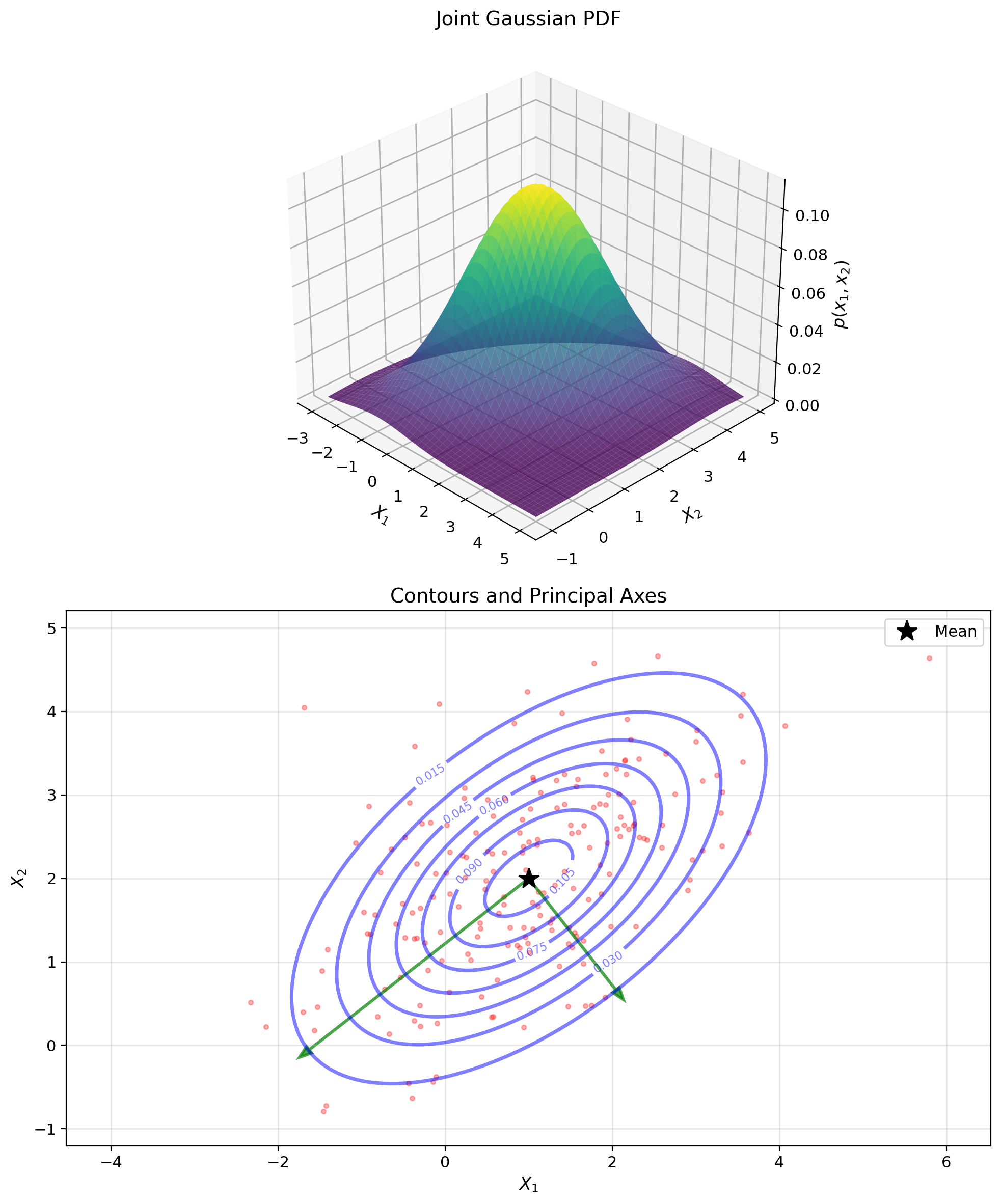

Positive Definite Matrices Define Ellipsoids

Definition: \(A\) is positive definite if \[\mathbf{x}^T A \mathbf{x} > 0 \quad \text{for all } \mathbf{x} \neq \mathbf{0}\]

Equivalent conditions:

- All eigenvalues \(\lambda_i > 0\)

- \(A = B^TB\) for some invertible \(B\)

- All leading principal minors positive

Geometric interpretation:

The set \(\{\mathbf{x} : \mathbf{x}^T A \mathbf{x} = 1\}\) is an ellipsoid.

- Principal axes: eigenvectors of \(A\)

- Axis lengths: \(1/\sqrt{\lambda_i}\)

Why this matters:

Covariance matrices are always positive semi-definite.

The “shape” of a data cloud is an ellipsoid determined by its covariance.

Random Vectors Have Covariance Matrices

Random vector: \(\mathbf{X} = [X_1, X_2, ..., X_n]^T\)

Mean vector: \[\boldsymbol{\mu} = \mathbb{E}[\mathbf{X}] = [\mathbb{E}[X_1], ..., \mathbb{E}[X_n]]^T\]

Covariance matrix: \[K = \mathbb{E}[(\mathbf{X} - \boldsymbol{\mu})(\mathbf{X} - \boldsymbol{\mu})^T]\]

Entry \((i,j)\): \[K_{ij} = \text{Cov}(X_i, X_j)\]

Properties:

- Symmetric: \(K = K^T\)

- Positive semi-definite: \(\mathbf{a}^T K \mathbf{a} \geq 0\)

- Diagonal entries = variances: \(K_{ii} = \text{Var}(X_i)\)

Covariance ellipse:

For 2D data, the ellipse \((\mathbf{x} - \boldsymbol{\mu})^T K^{-1} (\mathbf{x} - \boldsymbol{\mu}) = c^2\) contains approximately 95% of data when \(c \approx 2.45\).

Orthogonality of Random Variables = Orthogonality of Vectors

Random variable inner product:

Define \(\langle X, Y \rangle = \mathbb{E}[XY]\)

For zero-mean variables: \[\langle X, Y \rangle = \mathbb{E}[XY] = \text{Cov}(X, Y)\]

Orthogonal random variables: \[X \perp Y \iff \mathbb{E}[XY] = 0\]

(For zero-mean: \(\text{Cov}(X,Y) = 0\))

The connection:

| Vectors | Random Variables |

|---|---|

| \(\langle \mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y} \rangle = \mathbf{x}^T\mathbf{y}\) | \(\langle X, Y \rangle = \mathbb{E}[XY]\) |

| \(\mathbf{x} \perp \mathbf{y}\) | \(X \perp Y\) |

| Projection minimizes \(\|\mathbf{y} - \hat{\mathbf{y}}\|^2\) | LMMSE minimizes \(\mathbb{E}[(Y - \hat{Y})^2]\) |

| Error \(\perp\) subspace | Error \(\perp\) predictors |

This is why linear algebra solves estimation problems.

Linear Restriction Makes MMSE Tractable

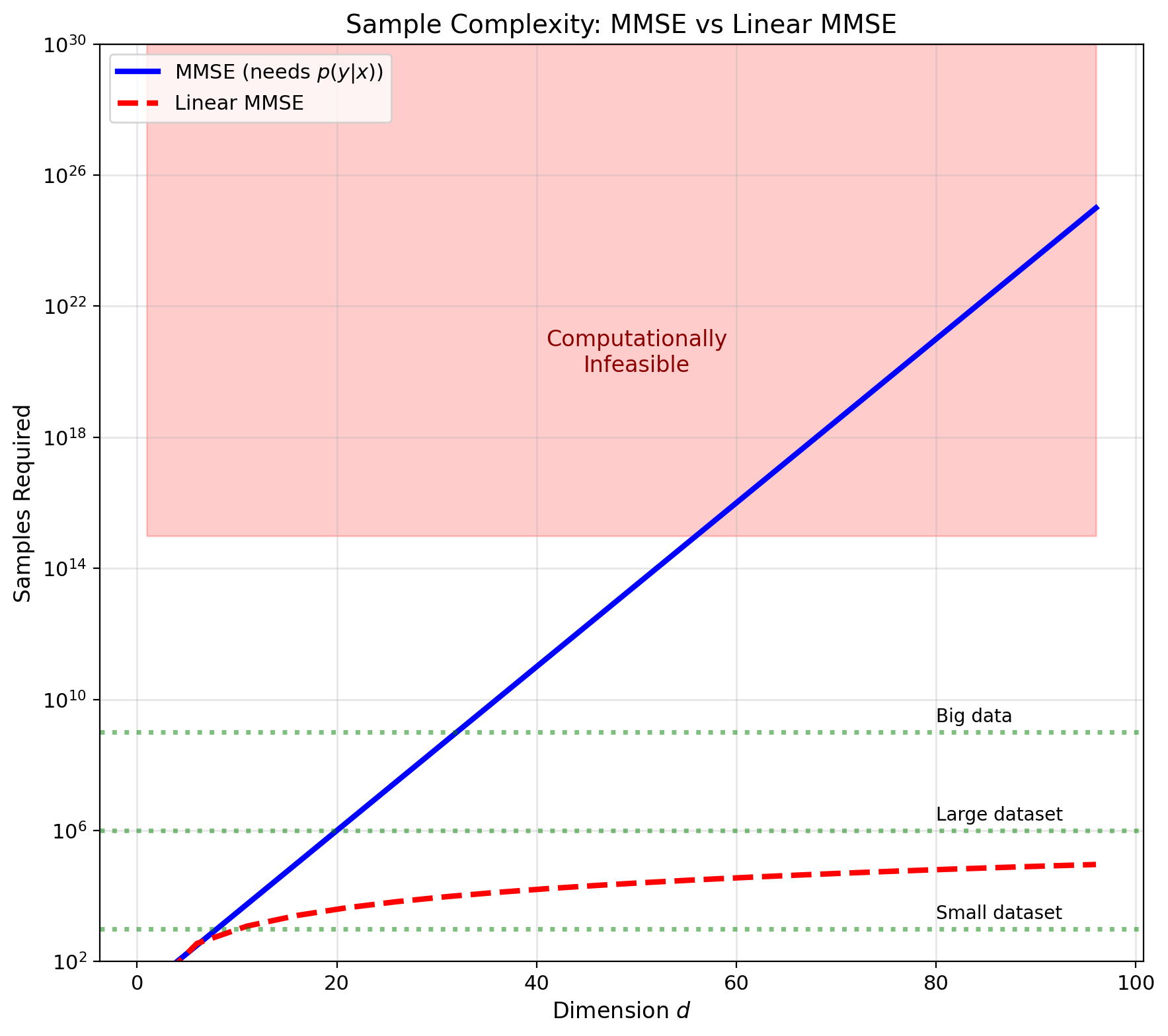

Density Estimation Needs Exponential Samples

Curse of dimensionality:

To compute \(\mathbb{E}[Y|X]\), need \(p(y|x)\)

Density estimation convergence:

- Rate: \(N^{-4/(d+4)}\) for \(d\)-dimensional data

- \(d = 10\): Need \(N \approx 10^6\) samples

- \(d = 100\): Need \(N \approx 10^{20}\) samples!

Why this matters:

- Modern data is high-dimensional

- Never have enough samples for nonparametric methods

- Must accept suboptimality for tractability

Linear class advantages:

- Only need second moments: \(O(d^2)\) parameters

- Sample complexity: \(O(d^2)\) vs \(O(e^d)\)

- Often captures dominant effects

Moments Are Computable; Densities Are Not

MMSE requires \(p(y|x)\) to compute \(\mathbb{E}[Y|X]\)

Reality: We rarely know conditional distributions

What we often have:

- Sample data: \((x_1, y_1), ..., (x_n, y_n)\)

- First and second moments

- Rough sense of relationship

Practical solution: Restrict to linear predictors \[\hat{Y} = aX + b\]

- Only need means, variances, covariance

- Optimal for Gaussian (prove in Part 5)

- Often good enough in practice

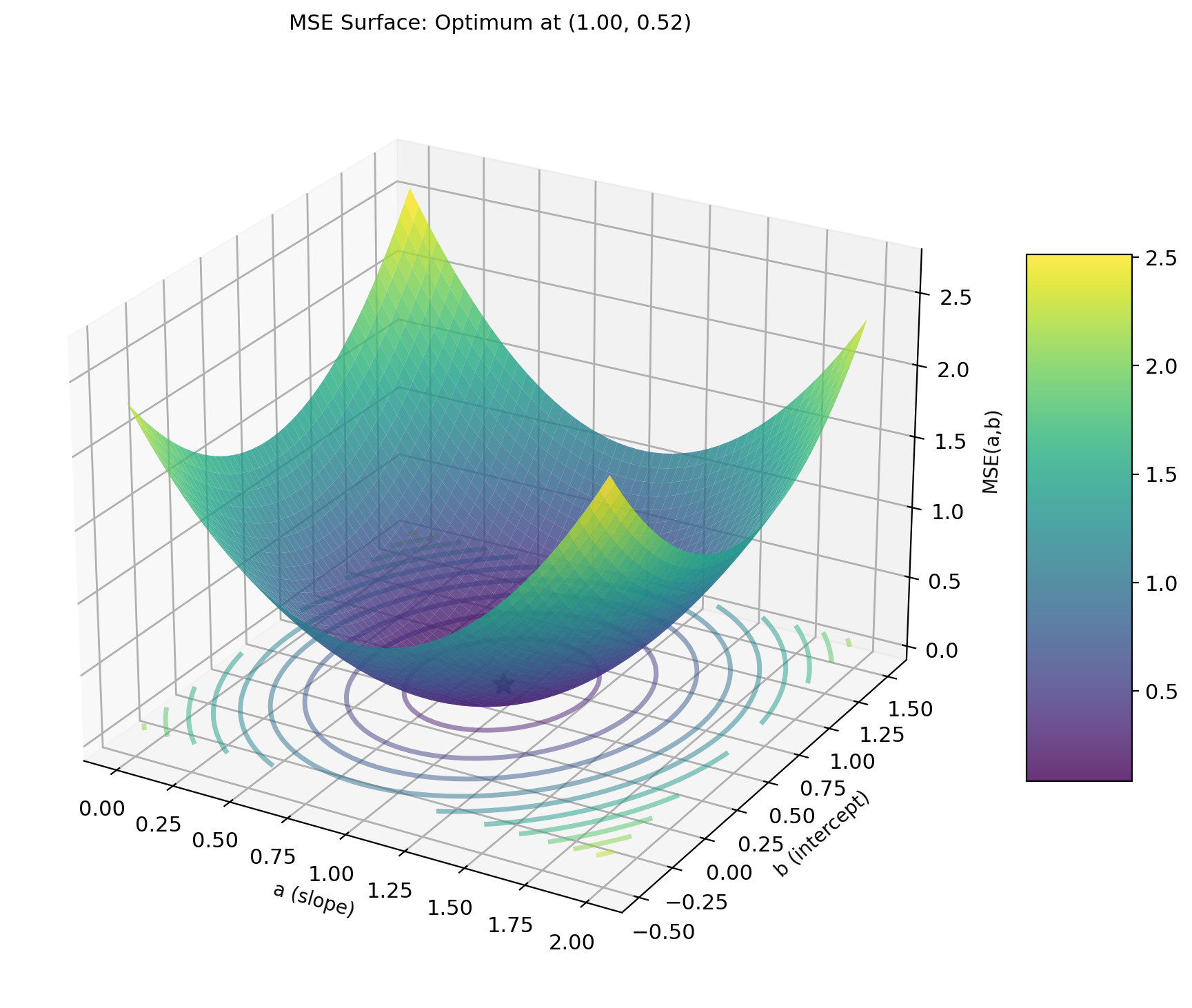

Linear Class: Two Parameters Instead of ∞

Function class: \[\mathcal{L} = \{g(x) = ax + b : a, b \in \mathbb{R}\}\]

New optimization problem: \[\min_{a,b} \text{MSE}(a,b) = \min_{a,b} \mathbb{E}[(Y - aX - b)^2]\]

From infinite to finite:

- Before: Search over all functions

- Now: Search over 2 parameters

Expanding the MSE: \[\text{MSE}(a,b) = \mathbb{E}[Y^2 - 2Y(aX + b) + (aX + b)^2]\] \[= \mathbb{E}[Y^2] - 2a\mathbb{E}[XY] - 2b\mathbb{E}[Y]\] \[+ a^2\mathbb{E}[X^2] + 2ab\mathbb{E}[X] + b^2\]

MSE is quadratic in \((a, b)\)

- Unique minimum (if Var\((X) > 0\))

- Closed-form solution via derivatives

- No iterative optimization needed

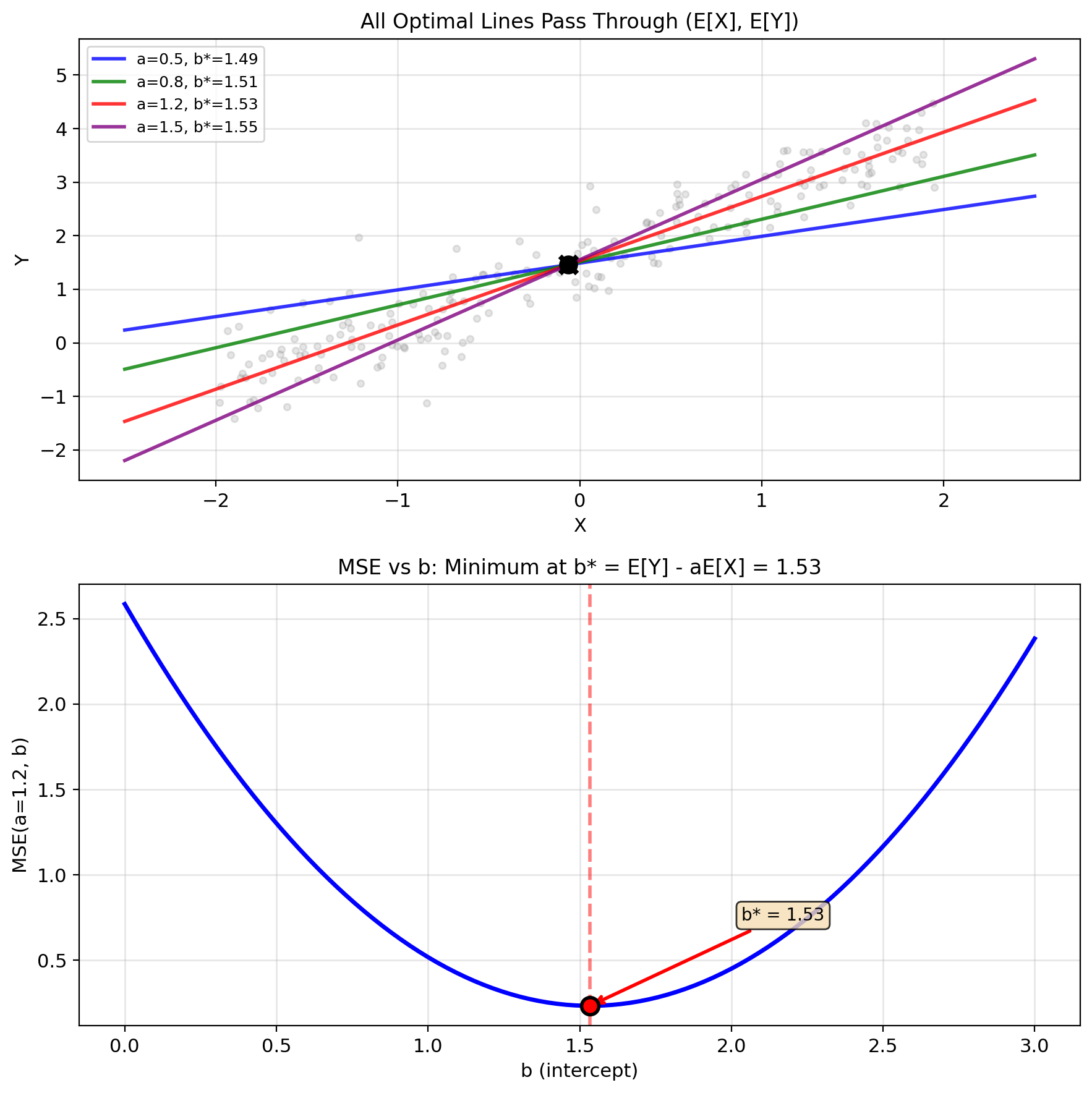

Optimal Offset Forces Zero Mean Error

Step 1: Find optimal \(b\) for fixed \(a\)

Take derivative with respect to \(b\): \[\frac{\partial}{\partial b}\text{MSE}(a,b) = \frac{\partial}{\partial b}\mathbb{E}[(Y - aX - b)^2]\]

\[= -2\mathbb{E}[Y - aX - b] = 0\]

Solving for \(b\): \[\mathbb{E}[Y - aX - b] = 0\] \[\mathbb{E}[Y] - a\mathbb{E}[X] - b = 0\]

\[\boxed{b^* = \mathbb{E}[Y] - a\mathbb{E}[X]}\]

Interpretation:

- Offset ensures zero mean error

- Forces predictor through \((\mathbb{E}[X], \mathbb{E}[Y])\)

- Adjusts for non-zero means

Substituting back: \[\hat{Y} = aX + \mathbb{E}[Y] - a\mathbb{E}[X] = \mathbb{E}[Y] + a(X - \mathbb{E}[X])\]

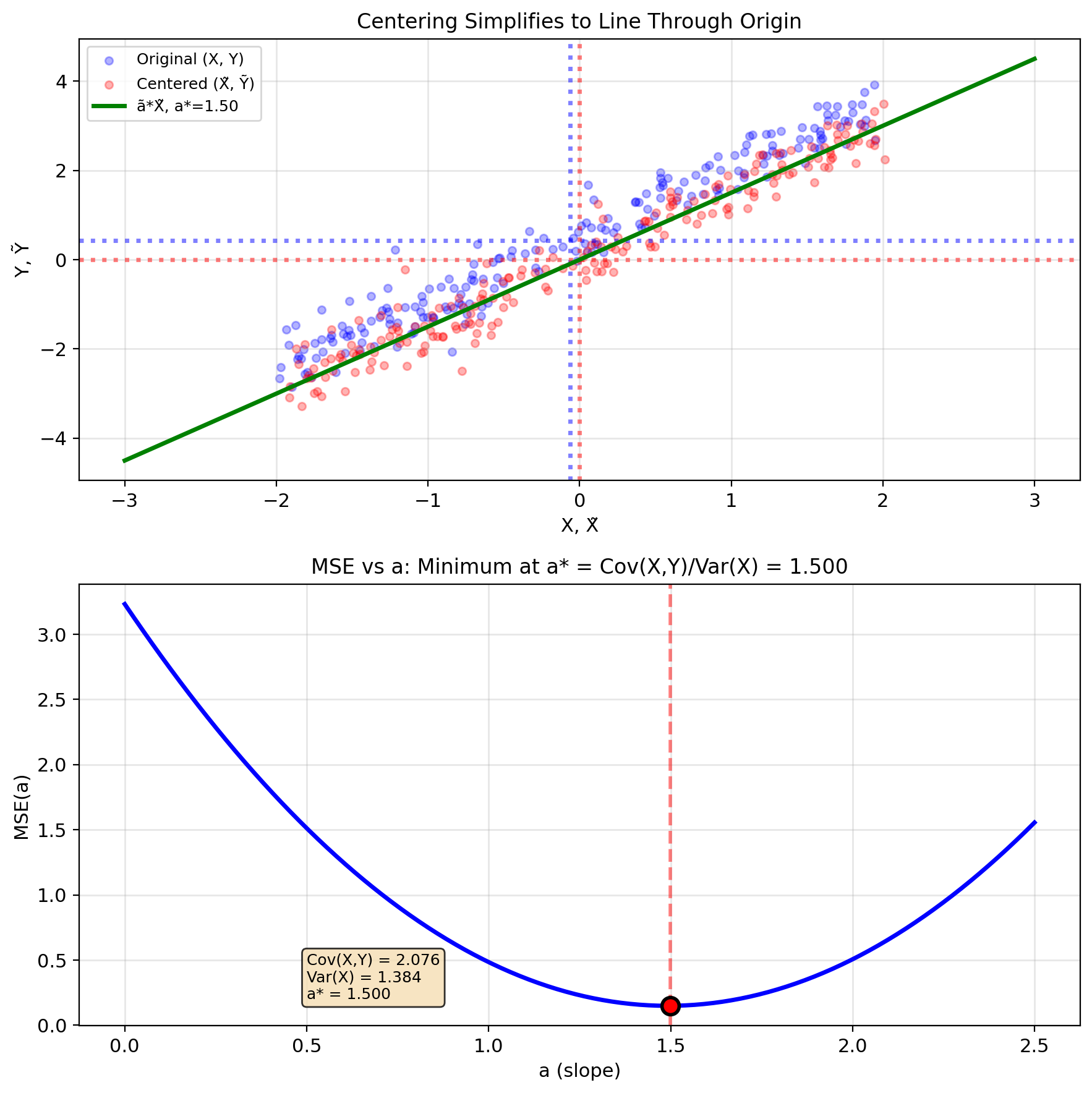

Optimal Slope = Cov(X,Y)/Var(X)

Step 2: Find optimal \(a\) using \(b^* = \mathbb{E}[Y] - a\mathbb{E}[X]\)

Substitute into MSE: \[\text{MSE}(a) = \mathbb{E}[(Y - \mathbb{E}[Y] - a(X - \mathbb{E}[X]))^2]\]

Define centered variables:

- \(\tilde{Y} = Y - \mathbb{E}[Y]\)

- \(\tilde{X} = X - \mathbb{E}[X]\)

Then: \(\text{MSE}(a) = \mathbb{E}[(\tilde{Y} - a\tilde{X})^2]\)

Take derivative: \[\frac{d}{da}\text{MSE}(a) = -2\mathbb{E}[\tilde{X}(\tilde{Y} - a\tilde{X})] = 0\]

\[\mathbb{E}[\tilde{X}\tilde{Y}] - a\mathbb{E}[\tilde{X}^2] = 0\]

Solution: \[\boxed{a^* = \frac{\mathbb{E}[\tilde{X}\tilde{Y}]}{\mathbb{E}[\tilde{X}^2]} = \frac{\text{Cov}(X,Y)}{\text{Var}(X)}}\]

Note: \(\mathbb{E}[\tilde{X}\tilde{Y}] = \text{Cov}(X,Y)\) and \(\mathbb{E}[\tilde{X}^2] = \text{Var}(X)\)

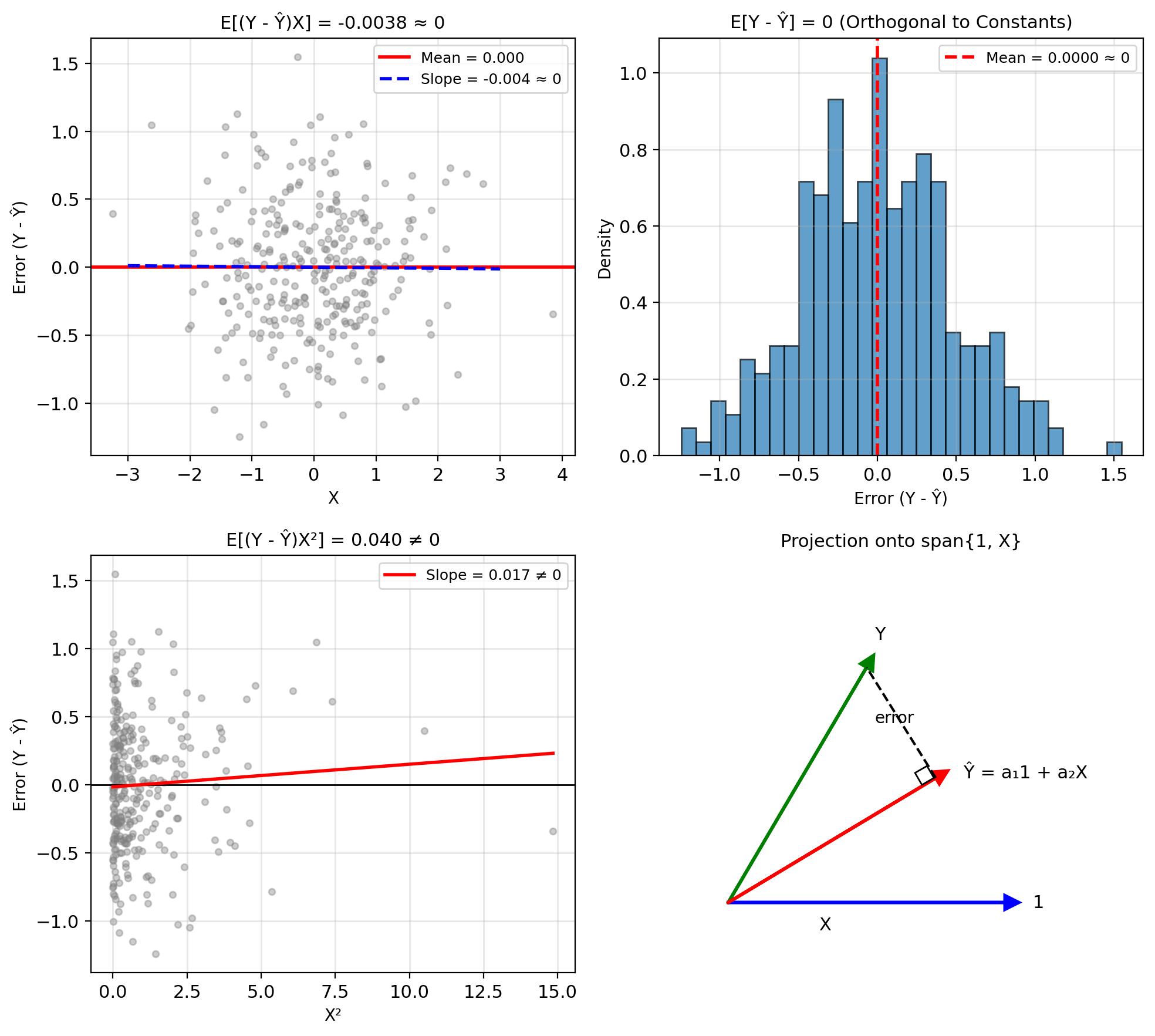

Same Solution from Orthogonality Conditions

Alternative approach: Require error orthogonal to predictors

From MMSE theory: optimal error satisfies \[\mathbb{E}[(Y - \hat{Y}) \cdot h(X)] = 0\] for functions \(h\) in the predictor class.

For linear predictors \(\hat{Y} = aX + b\):

Predictor class = span\(\{1, X\}\)

Orthogonality conditions:

\(\mathbb{E}[(Y - aX - b) \cdot 1] = 0\) \[\mathbb{E}[Y] - a\mathbb{E}[X] - b = 0\] \[\boxed{b = \mathbb{E}[Y] - a\mathbb{E}[X]}\]

\(\mathbb{E}[(Y - aX - b) \cdot X] = 0\) \[\mathbb{E}[XY] - a\mathbb{E}[X^2] - b\mathbb{E}[X] = 0\]

Substitute \(b\) and solve: \[\boxed{a = \frac{\text{Cov}(X,Y)}{\text{Var}(X)}}\]

Same answer, different route

- Calculus: minimize MSE directly

- Orthogonality: project onto subspace

Orthogonality generalizes to vectors without derivatives.

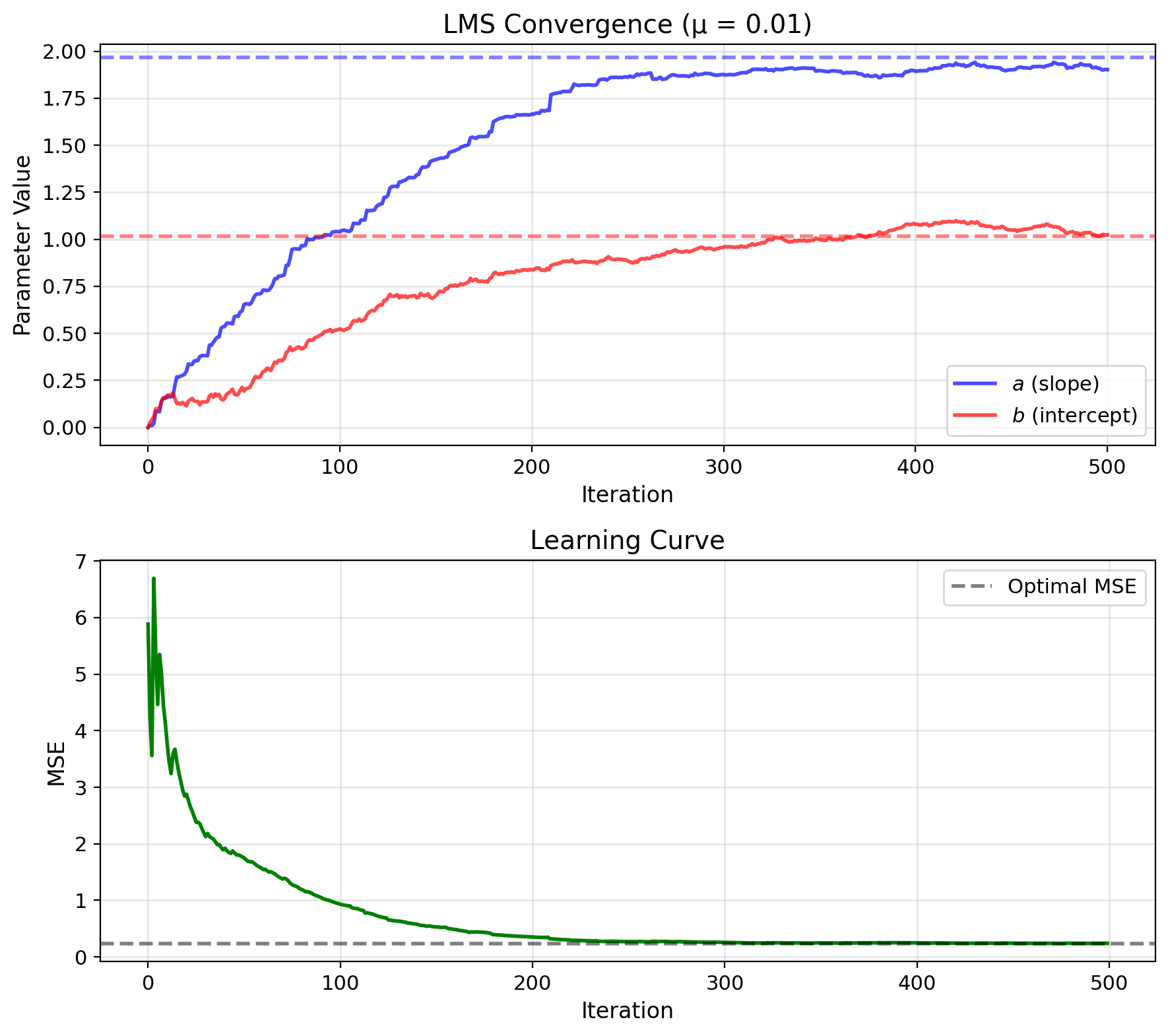

LMS Learns LMMSE from Streaming Data

Problem: Don’t know statistics a priori

LMMSE needs: \(\text{Cov}(X,Y)\) and \(\text{Var}(X)\)

Solution: Learn from streaming data

Gradient descent on MSE: \[\frac{\partial}{\partial a} \mathbb{E}[(Y - aX - b)^2] = -2\mathbb{E}[(Y - aX - b)X]\]

Widrow-Hoff insight:

Replace expectation with instantaneous value: \[\mathbb{E}[(Y - aX - b)X] \approx (y_i - ax_i - b)x_i = e_i x_i\]

LMS update rule: \[a_{i+1} = a_i + \mu e_i x_i\] \[b_{i+1} = b_i + \mu e_i\]

where \(e_i = y_i - \hat{y}_i\) is prediction error

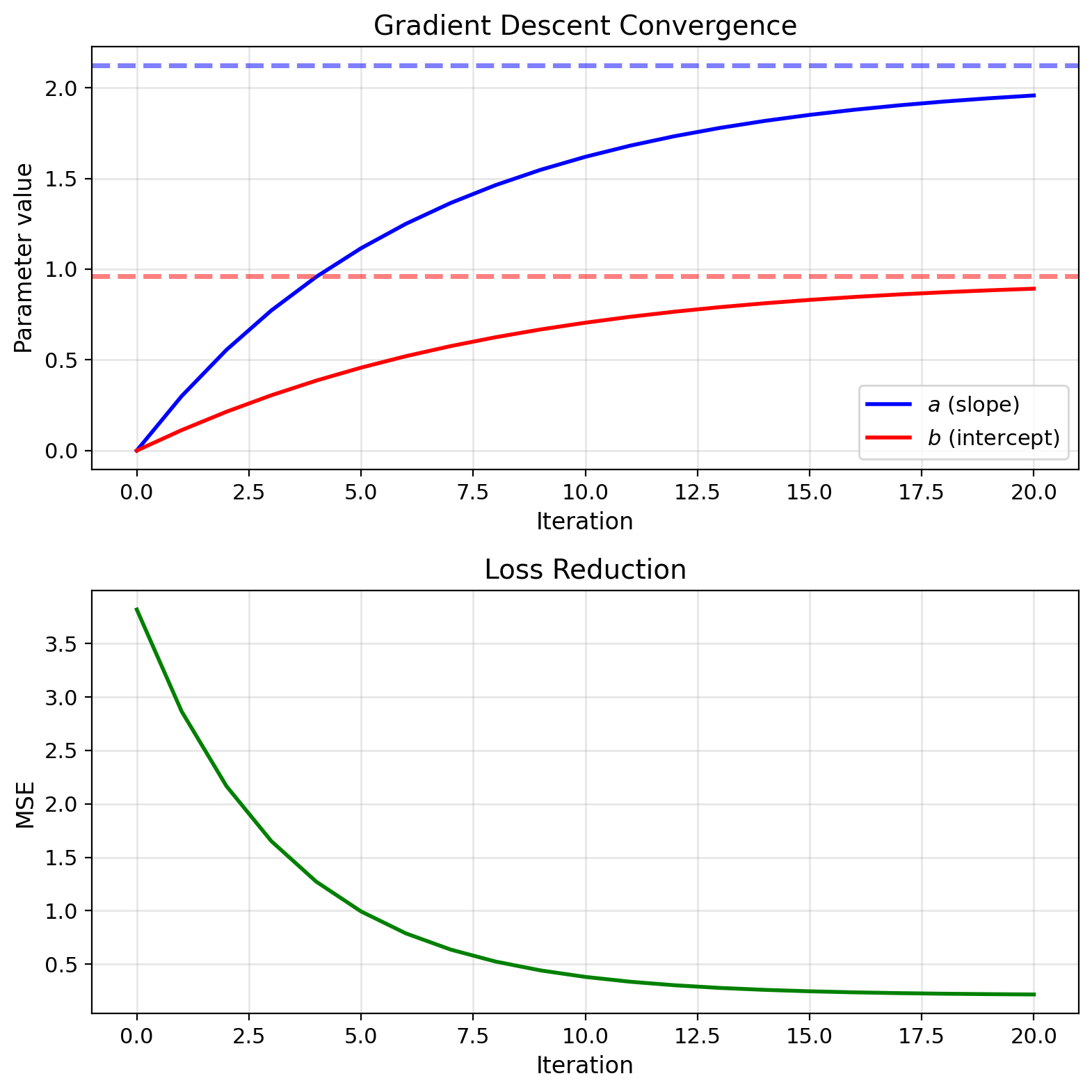

Convergence: \(a_i \to a^*_{\text{LMMSE}}\) as \(i \to \infty\)

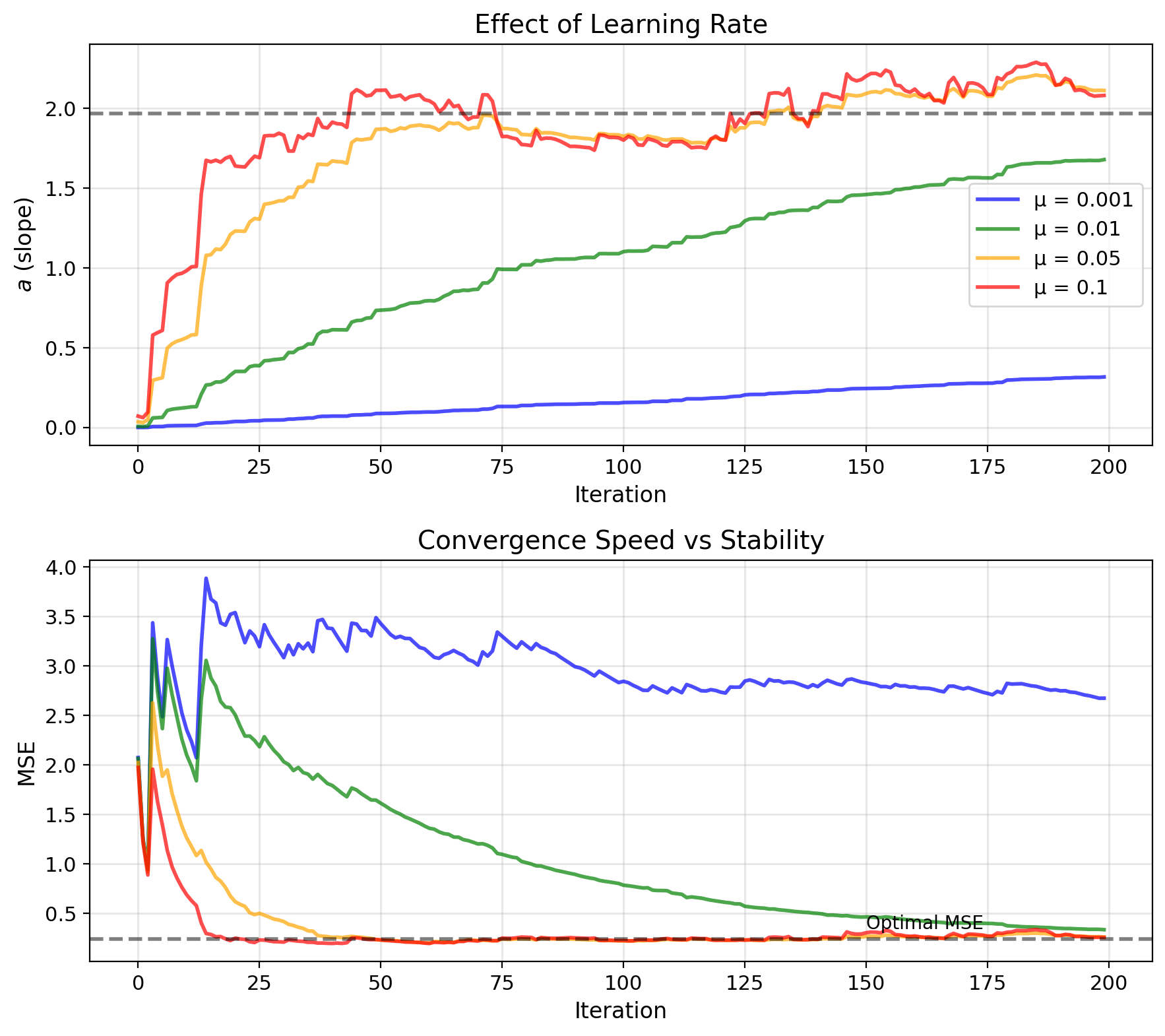

Learning Rate Trades Convergence for Variance

Convergence condition: \[0 < \mu < \frac{2}{\mathbb{E}[X^2]}\]

Too large \(\mu\) → divergence

Steady-state error:

Misadjustment: \(M = \frac{\mu \mathbb{E}[X^2]}{2}\)

Trade-off:

- Small \(\mu\): Slow convergence, low steady-state error

- Large \(\mu\): Fast convergence, high steady-state error

Time constant: \[\tau \approx \frac{1}{2\mu \mathbb{E}[X^2]}\]

iterations to converge

Advantages:

- No matrix operations

- Adapts to changing statistics

- Simple hardware implementation

Relation: LMS = stochastic gradient descent for MSE

LMMSE Needs Only Means and Covariances

Complete solution: \[\boxed{\hat{Y}_{\text{LMMSE}} = \mathbb{E}[Y] + \frac{\text{Cov}(X,Y)}{\text{Var}(X)}(X - \mathbb{E}[X])}\]

Alternative forms:

Using correlation \(\rho = \frac{\text{Cov}(X,Y)}{\sigma_X \sigma_Y}\): \[\hat{Y}_{\text{LMMSE}} = \mathbb{E}[Y] + \rho\frac{\sigma_Y}{\sigma_X}(X - \mathbb{E}[X])\]

Standardized form: If \(\mathbb{E}[X] = \mathbb{E}[Y] = 0\) and \(\sigma_X = \sigma_Y = 1\): \[\hat{Y}_{\text{LMMSE}} = \rho X\]

Minimum MSE: \[\text{MSE}_{\text{LMMSE}} = \text{Var}(Y)(1 - \rho^2)\]

Properties:

- Only needs first and second moments

- Always exists (if Var\((X) > 0\))

- Unique solution

- Orthogonal errors: \(\mathbb{E}[(Y - \hat{Y})X] = 0\)

ρ² = Fraction of Variance Explained

Slope decomposition: \[a^* = \frac{\text{Cov}(X,Y)}{\text{Var}(X)} = \frac{\rho \sigma_X \sigma_Y}{\sigma_X^2} = \rho \frac{\sigma_Y}{\sigma_X}\]

Correlation determines predictability

Fraction of variance explained: \[R^2 = \frac{\text{Var}(Y) - \text{MSE}_{\text{LMMSE}}}{\text{Var}(Y)} = \rho^2\]

Correlation measures linear predictability, not general dependence

LMMSE = MMSE Iff E[Y|X] Is Linear

Fundamental inequality: \[\text{MSE}_{\text{LMMSE}} \geq \text{MSE}_{\text{MMSE}}\]

Always! Linear is restricted class.

Performance gap: \[\text{MSE}_{\text{LMMSE}} - \text{MSE}_{\text{MMSE}} = \mathbb{E}[(\mathbb{E}[Y|X] - \hat{Y}_{\text{LMMSE}})^2]\]

Measures nonlinearity of \(\mathbb{E}[Y|X]\).

When are they equal? \[\text{MSE}_{\text{LMMSE}} = \text{MSE}_{\text{MMSE}}\] if and only if \(\mathbb{E}[Y|X]\) is linear in \(X\).

For jointly Gaussian \((X,Y)\):

- \(\mathbb{E}[Y|X]\) is linear

- LMMSE = MMSE

- No performance loss from restriction

LMMSE Error ⊥ {1, X}, Not All h(X)

MMSE (unrestricted): \[\mathbb{E}[(Y - \mathbb{E}[Y|X]) \cdot h(X)] = 0 \quad \text{for all } h\]

LMMSE (restricted): \[\mathbb{E}[(Y - \hat{Y}_{\text{LMMSE}}) \cdot h(X)] = 0 \quad \text{for } h \in \{1, X\}\]

LMMSE error may still correlate with \(X^2, X^3, \sin(X), ...\)

\[\mathbb{E}[(Y - \hat{Y}_{\text{LMMSE}}) \cdot X^2] \neq 0 \text{ (in general)}\]

This correlation is unexploited information—structure in \((X, Y)\) that linear predictors cannot capture.

When LMMSE achieves MMSE:

If \(\mathbb{E}[Y|X]\) is already linear in \(X\):

- LMMSE error ⊥ all \(h(X)\) automatically

- No nonlinear structure to exploit

- Gaussian \((X,Y)\) guarantees this

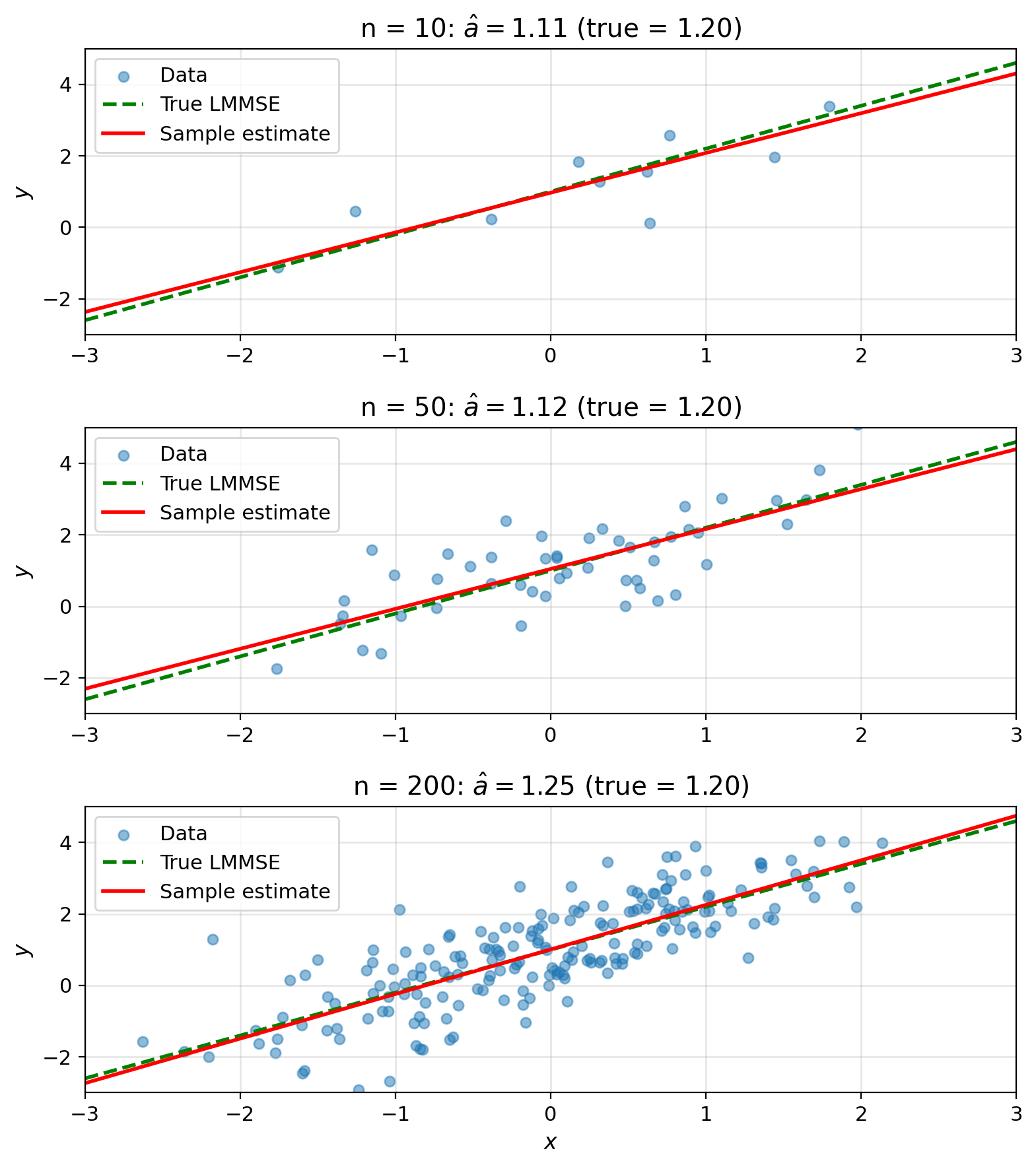

Sample Estimates Converge to Population LMMSE

What we need:

- \(\mathbb{E}[X], \mathbb{E}[Y]\)

- \(\mathbb{E}[X^2], \mathbb{E}[Y^2], \mathbb{E}[XY]\)

Sample estimates from data \((x_1, y_1), ..., (x_n, y_n)\): \[\hat{\mu}_X = \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n x_i, \quad \hat{\mu}_Y = \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n y_i\]

\[\widehat{\text{Var}}(X) = \frac{1}{n-1}\sum_{i=1}^n (x_i - \hat{\mu}_X)^2\]

\[\widehat{\text{Cov}}(X,Y) = \frac{1}{n-1}\sum_{i=1}^n (x_i - \hat{\mu}_X)(y_i - \hat{\mu}_Y)\]

Then: \(\hat{a} = \widehat{\text{Cov}}(X,Y)/\widehat{\text{Var}}(X)\)

Gaussian Makes Linear Optimal

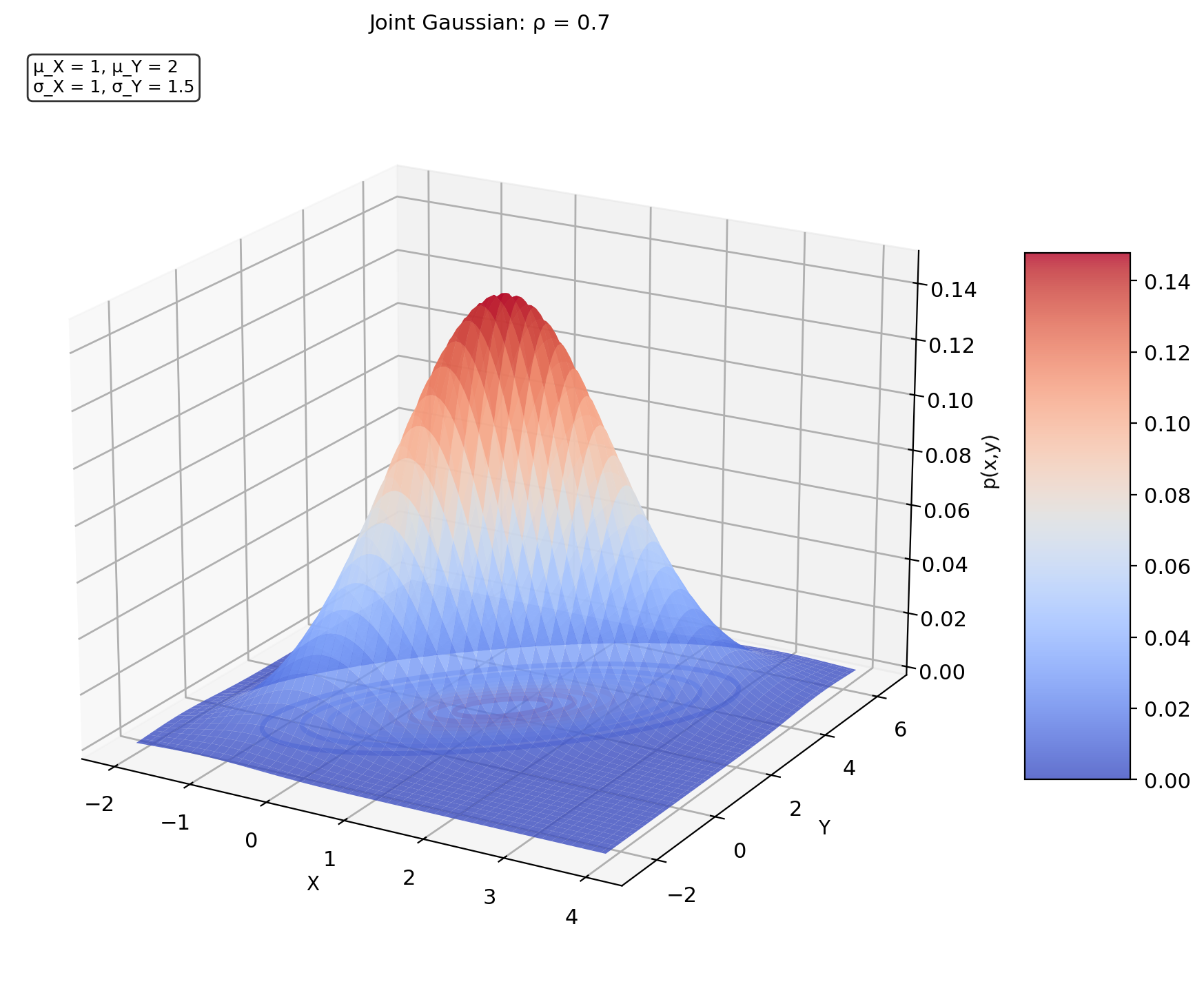

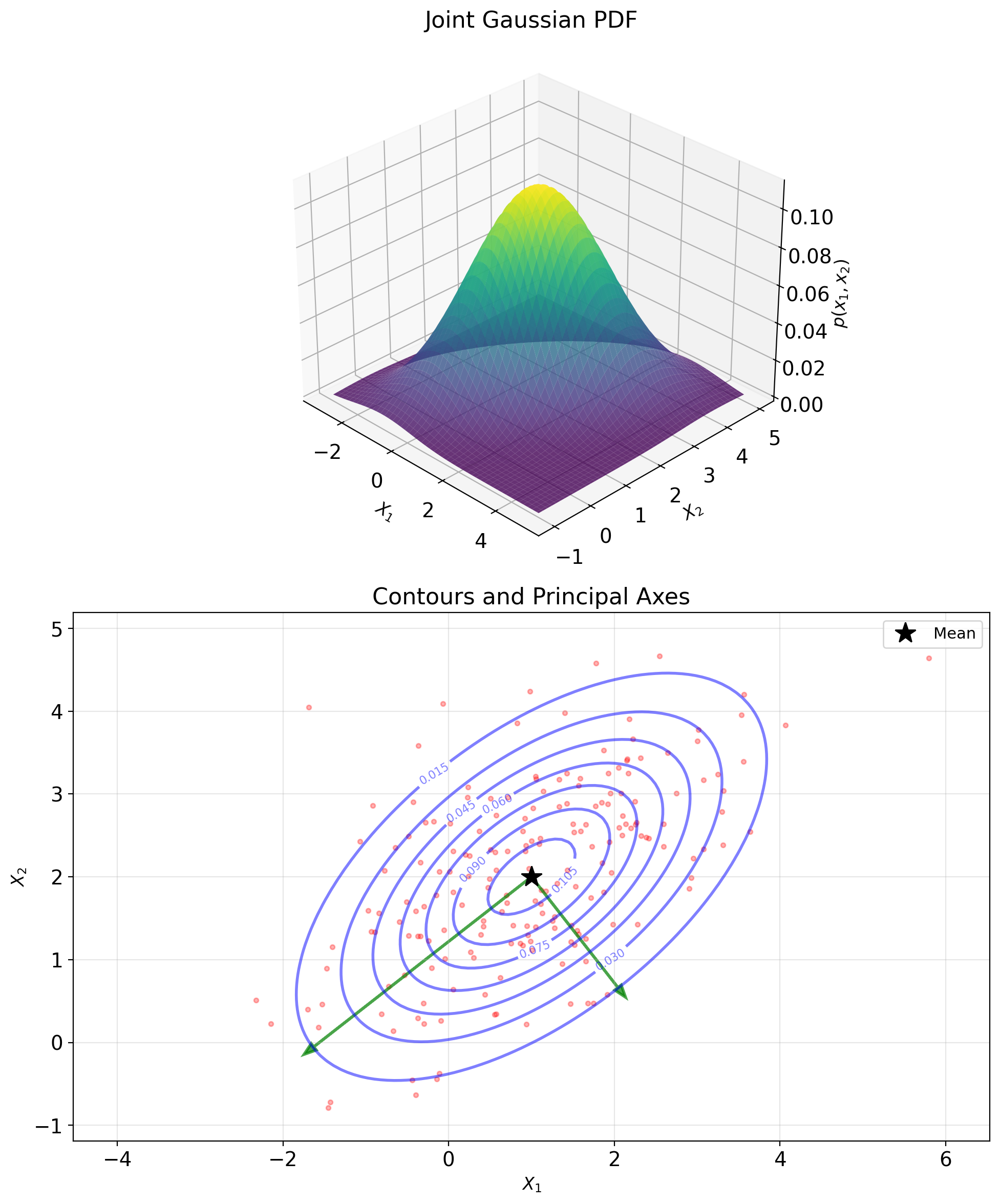

Five Parameters Specify the Bivariate Gaussian

Bivariate Gaussian \((X, Y) \sim \mathcal{N}(\mu, K)\)

Parameters: \[\mu = \begin{bmatrix} \mu_X \\ \mu_Y \end{bmatrix}, \quad K = \begin{bmatrix} \sigma_X^2 & k_{XY} \\ k_{XY} & \sigma_Y^2 \end{bmatrix}\]

where \(k_{XY} = \rho\sigma_X\sigma_Y\)

Joint density: \[p(x,y) = \frac{1}{2\pi\sigma_X\sigma_Y\sqrt{1-\rho^2}} \exp\left(-\frac{1}{2(1-\rho^2)}\left[z_x^2 - 2\rho z_x z_y + z_y^2\right]\right)\]

where \(z_x = \frac{x-\mu_X}{\sigma_X}\) and \(z_y = \frac{y-\mu_Y}{\sigma_Y}\) are standardized variables

Fully determined by first and second moments

- 5 parameters: \(\mu_X, \mu_Y, \sigma_X^2, \sigma_Y^2, \rho\)

- All higher moments determined by these

Gaussian Y|X Has Linear Mean, Constant Variance

Result: \(Y|X=x\) is Gaussian

Conditional mean: \[\mathbb{E}[Y|X=x] = \mu_Y + \rho\frac{\sigma_Y}{\sigma_X}(x - \mu_X)\]

Conditional variance (constant!): \[\text{Var}(Y|X=x) = \sigma_Y^2(1 - \rho^2)\]

Therefore: \[Y|X=x \sim \mathcal{N}\left(\mu_Y + \rho\frac{\sigma_Y}{\sigma_X}(x - \mu_X), \sigma_Y^2(1 - \rho^2)\right)\]

Observations:

- \(\mathbb{E}[Y|X=x]\) is linear in \(x\)

- \(\text{Var}(Y|X=x)\) independent of \(x\)

- Conditional distribution remains Gaussian

Regression line: \[y = \mu_Y + \rho\frac{\sigma_Y}{\sigma_X}(x - \mu_X)\] passes through \((\mu_X, \mu_Y)\) with slope \(\rho\sigma_Y/\sigma_X\)

Three Methods Give the Same Linear Formula

Method 1: Complete the square

Start with joint density, condition on \(X = x\): \[p(y|x) \propto \exp\left(-\frac{1}{2(1-\rho^2)\sigma_Y^2}\left(y - \mu_Y - \rho\frac{\sigma_Y}{\sigma_X}(x-\mu_X)\right)^2\right)\]

Method 2: Linear projection

Find \(a, b\) minimizing \(\mathbb{E}[(Y - aX - b)^2]\):

- \(a^* = \text{Cov}(X,Y)/\text{Var}(X) = \rho\sigma_Y/\sigma_X\)

- \(b^* = \mathbb{E}[Y] - a^*\mathbb{E}[X] = \mu_Y - a^*\mu_X\)

Method 3: Schur complement

Using block matrix operations on \(K\): \[\mathbb{E}[Y|X=x] = \mu_Y + k_{YX}k_{XX}^{-1}(x - \mu_X)\] \[= \mu_Y + \rho\sigma_X\sigma_Y \cdot \frac{1}{\sigma_X^2}(x - \mu_X)\]

(all methods give same result)

MMSE = LMMSE for Gaussian

Fundamental result: For jointly Gaussian \((X, Y)\)

\[\boxed{\hat{Y}_{\text{MMSE}} = \hat{Y}_{\text{LMMSE}} = \mu_Y + \rho\frac{\sigma_Y}{\sigma_X}(X - \mu_X)}\]

Why equal?

- MMSE: \(\hat{Y}_{\text{MMSE}} = \mathbb{E}[Y|X]\)

- For Gaussian: \(\mathbb{E}[Y|X]\) is linear

- LMMSE: Best linear predictor

Minimum MSE: \[\text{MSE}_{\min} = \sigma_Y^2(1 - \rho^2)\]

Implications:

- No need to consider nonlinear predictors

- Second moments sufficient for optimal prediction

- Closed-form solution

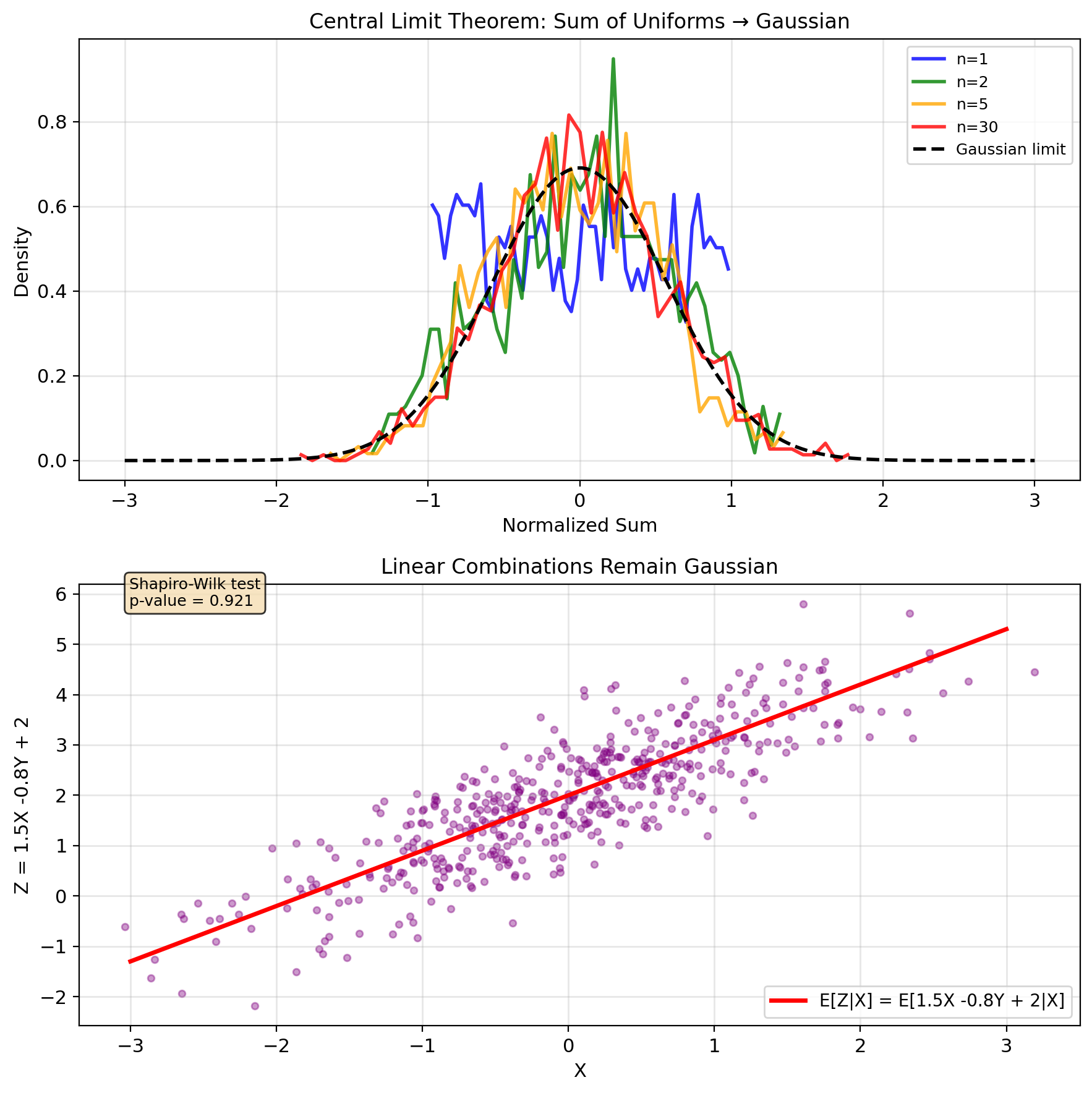

When Gaussian Assumptions Are Reasonable

Maximum entropy property: Among all distributions with given mean and covariance, Gaussian has maximum entropy \[H(X,Y) = -\int\int p(x,y)\log p(x,y) \, dx \, dy\]

Central Limit Theorem: Sum of many independent effects → Gaussian \[\frac{1}{\sqrt{n}}\sum_{i=1}^n X_i \xrightarrow{d} \mathcal{N}(\mu, \sigma^2)\]

Preserved under linear operations: If \((X,Y)\) Gaussian and \(Z = aX + bY + c\):

- \(Z\) is Gaussian

- \((X,Z)\) jointly Gaussian

- \((Y,Z)\) jointly Gaussian

Sufficient statistics: For Gaussian, sample mean and covariance are sufficient

- No information lost by summarizing with \((\bar{X}, \bar{Y}, S_{XX}, S_{YY}, S_{XY})\)

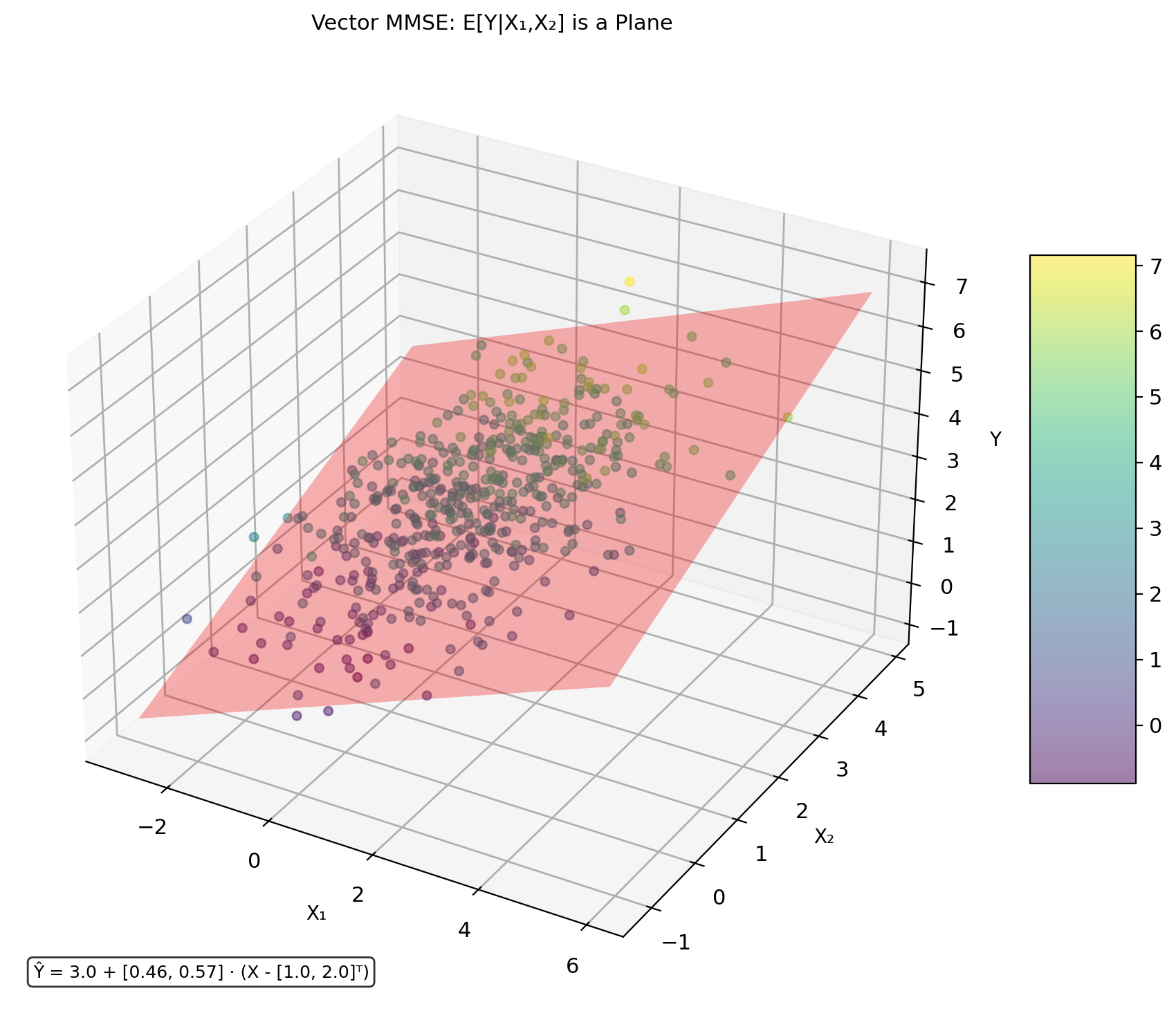

Vector Gaussian MMSE Requires Matrix Inversion

Multivariate Gaussian: \(\mathbf{X} = [X_1, ..., X_n]^T\), \(\mathbf{Y} = [Y_1, ..., Y_m]^T\)

Joint distribution: \[\begin{bmatrix} \mathbf{X} \\ \mathbf{Y} \end{bmatrix} \sim \mathcal{N}\left(\begin{bmatrix} \boldsymbol{\mu}_X \\ \boldsymbol{\mu}_Y \end{bmatrix}, \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf{K}_{XX} & \mathbf{K}_{XY} \\ \mathbf{K}_{YX} & \mathbf{K}_{YY} \end{bmatrix}\right)\]

MMSE estimator (still linear!): \[\hat{\mathbf{Y}}_{\text{MMSE}} = \mathbb{E}[\mathbf{Y}|\mathbf{X}] = \boldsymbol{\mu}_Y + \mathbf{K}_{YX}\mathbf{K}_{XX}^{-1}(\mathbf{X} - \boldsymbol{\mu}_X)\]

Error covariance: \[\mathbf{K}_{\mathbf{Y}|\mathbf{X}} = \mathbf{K}_{YY} - \mathbf{K}_{YX}\mathbf{K}_{XX}^{-1}\mathbf{K}_{XY}\]

Computational considerations:

- Matrix inversion: \(O(n^3)\)

- Numerical stability

- Regularization for singular \(\mathbf{K}_{XX}\)

Everything generalizes!

Sample LMMSE Equals Least Squares

Sample LMMSE Converges to Population LMMSE

Theory (Population)

Given joint distribution \(p(x,y)\): \[\text{MSE} = \mathbb{E}[(Y - \hat{Y})^2]\]

Linear MMSE solution: \[a^* = \frac{\text{Cov}(X,Y)}{\text{Var}(X)} = \frac{\mathbb{E}[XY] - \mathbb{E}[X]\mathbb{E}[Y]}{\mathbb{E}[X^2] - \mathbb{E}[X]^2}\]

Practice (Sample)

Given data \(\{(x_i, y_i)\}_{i=1}^n\): \[\text{MSE}_n = \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n (y_i - \hat{y}_i)^2\]

Sample estimates: \[\hat{a} = \frac{\sum_i (x_i - \bar{x})(y_i - \bar{y})}{\sum_i (x_i - \bar{x})^2}\]

Convergence: \(\hat{a} \to a^*\) as \(n \to \infty\) (law of large numbers)

This is linear regression

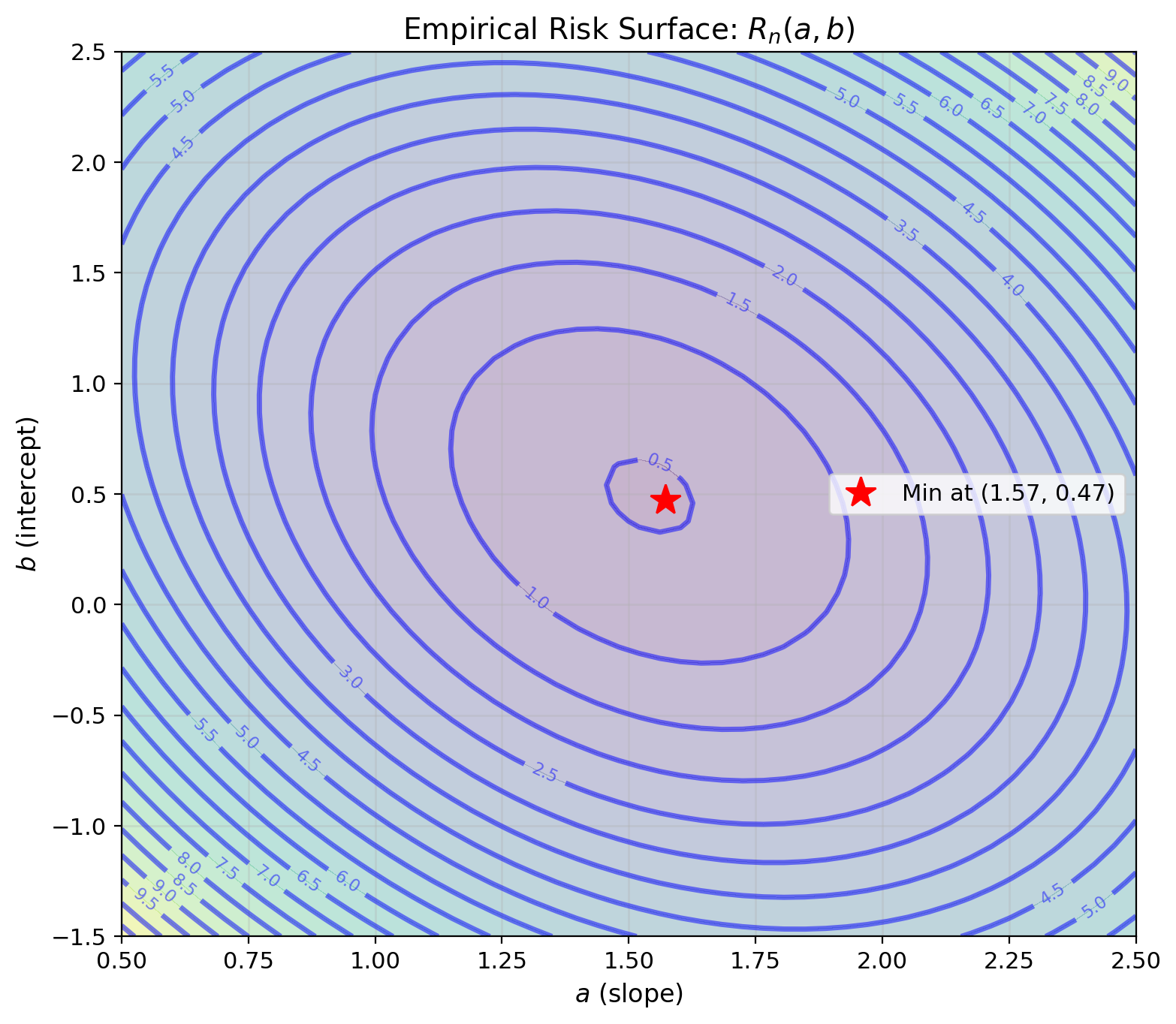

Minimizing Sample MSE = Least Squares

Population risk (unknown): \[R(a,b) = \mathbb{E}[(Y - aX - b)^2]\]

Empirical risk (computable): \[R_n(a,b) = \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n (y_i - ax_i - b)^2\]

Optimization: \[\frac{\partial R_n}{\partial b} = -\frac{2}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n (y_i - ax_i - b) = 0\] \[\implies b = \bar{y} - a\bar{x}\]

\[\frac{\partial R_n}{\partial a} = -\frac{2}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n x_i(y_i - ax_i - b) = 0\] \[\implies a = \frac{\sum_i x_i y_i - n\bar{x}\bar{y}}{\sum_i x_i^2 - n\bar{x}^2}\]

Sample optimization gives sample LMMSE

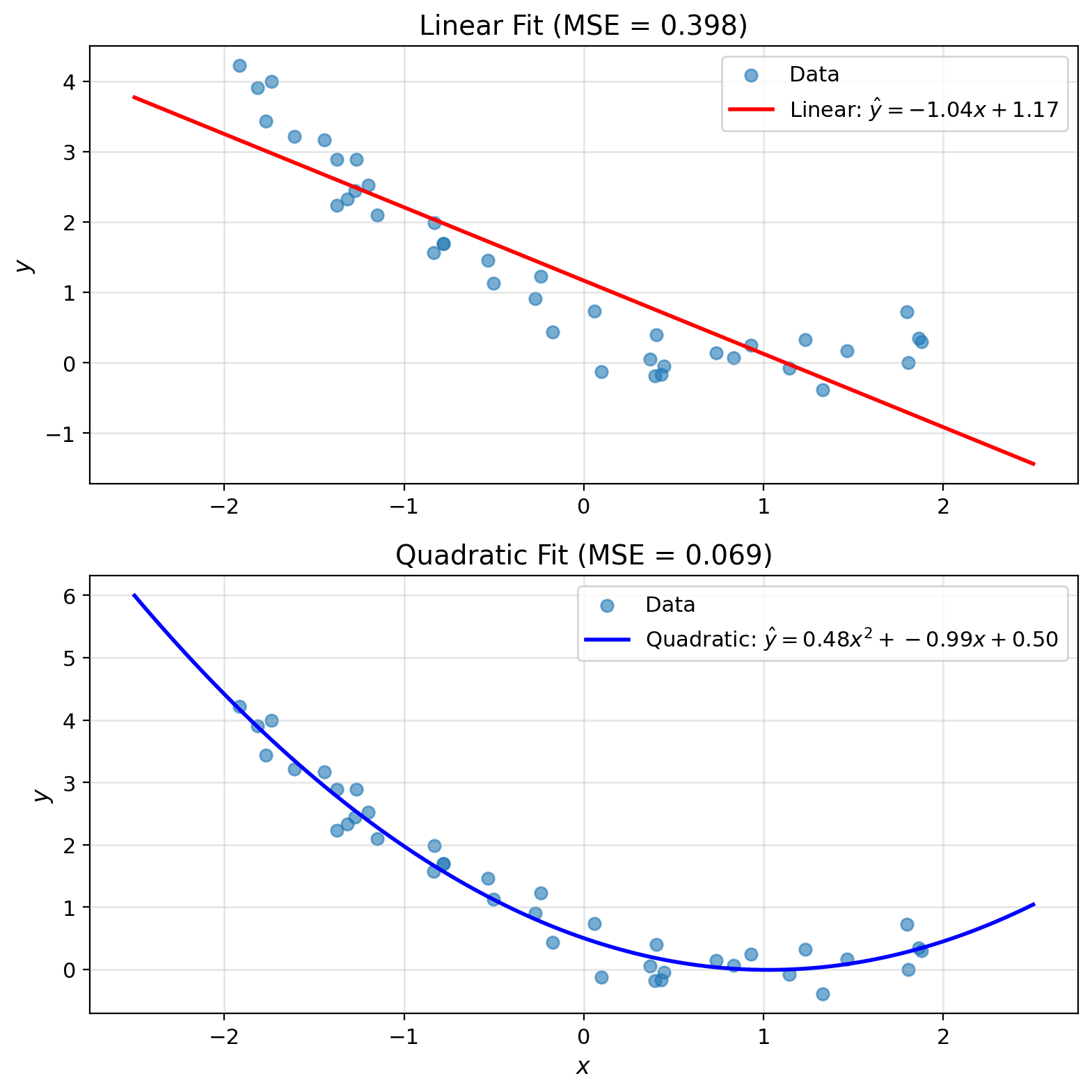

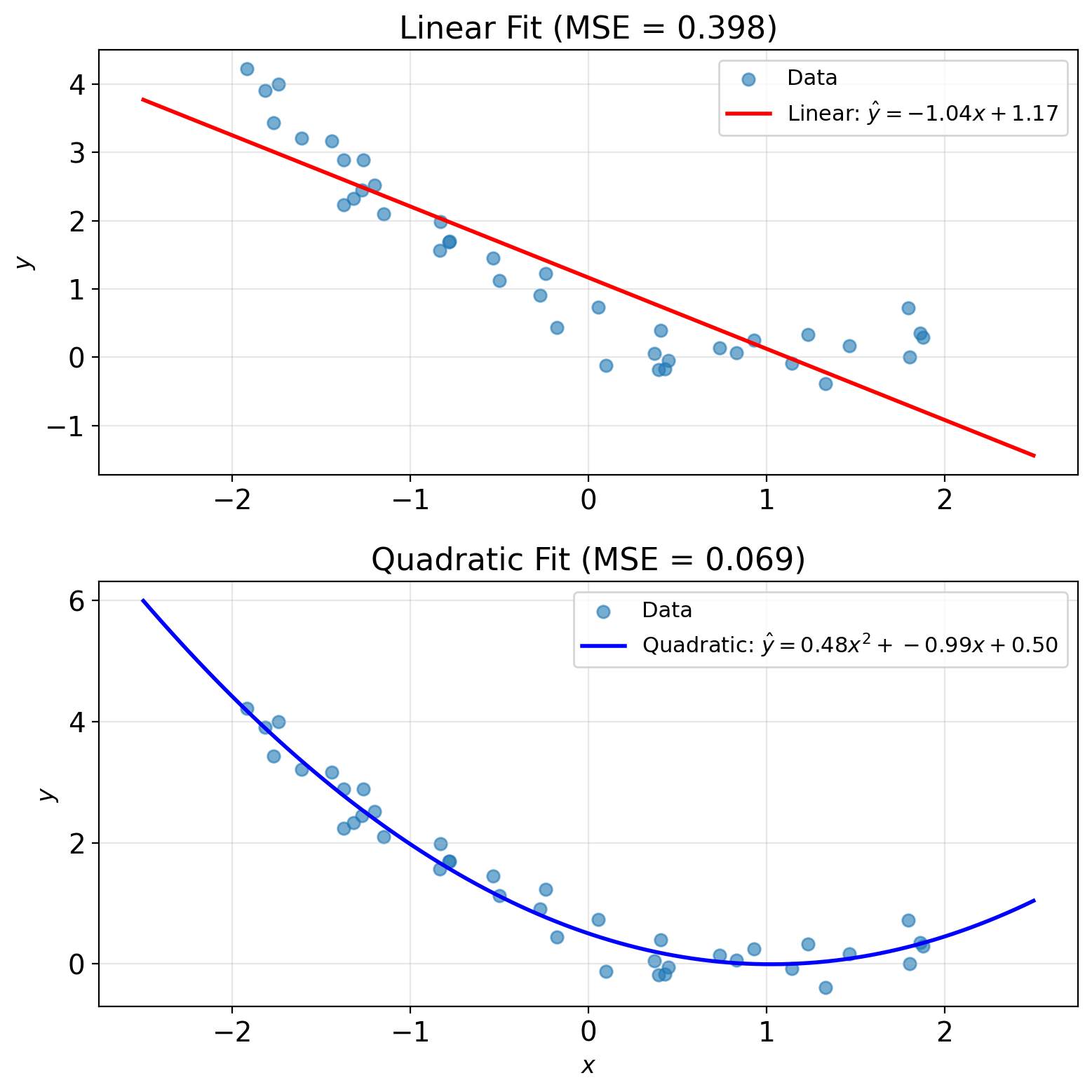

Feature Maps Enable Nonlinear Fits

Linear model limitations: \[\hat{y} = ax + b\]

Can only model linear relationships

Feature transformation: \[\hat{y} = \sum_{k=0}^{K} w_k \phi_k(x) = \mathbf{w}^T \boldsymbol{\phi}(x)\]

where \(\boldsymbol{\phi}(x) = [\phi_0(x), \phi_1(x), ..., \phi_K(x)]^T\)

Still linear MMSE in feature space:

- Design matrix: \(\Phi_{ij} = \phi_j(x_i)\)

- Solution: \(\mathbf{w}^* = (\Phi^T\Phi)^{-1}\Phi^T\mathbf{y}\)

Example: Polynomial features \[\phi_0(x) = 1, \quad \phi_1(x) = x, \quad \phi_2(x) = x^2\]

Now can fit parabolas while still using linear methods

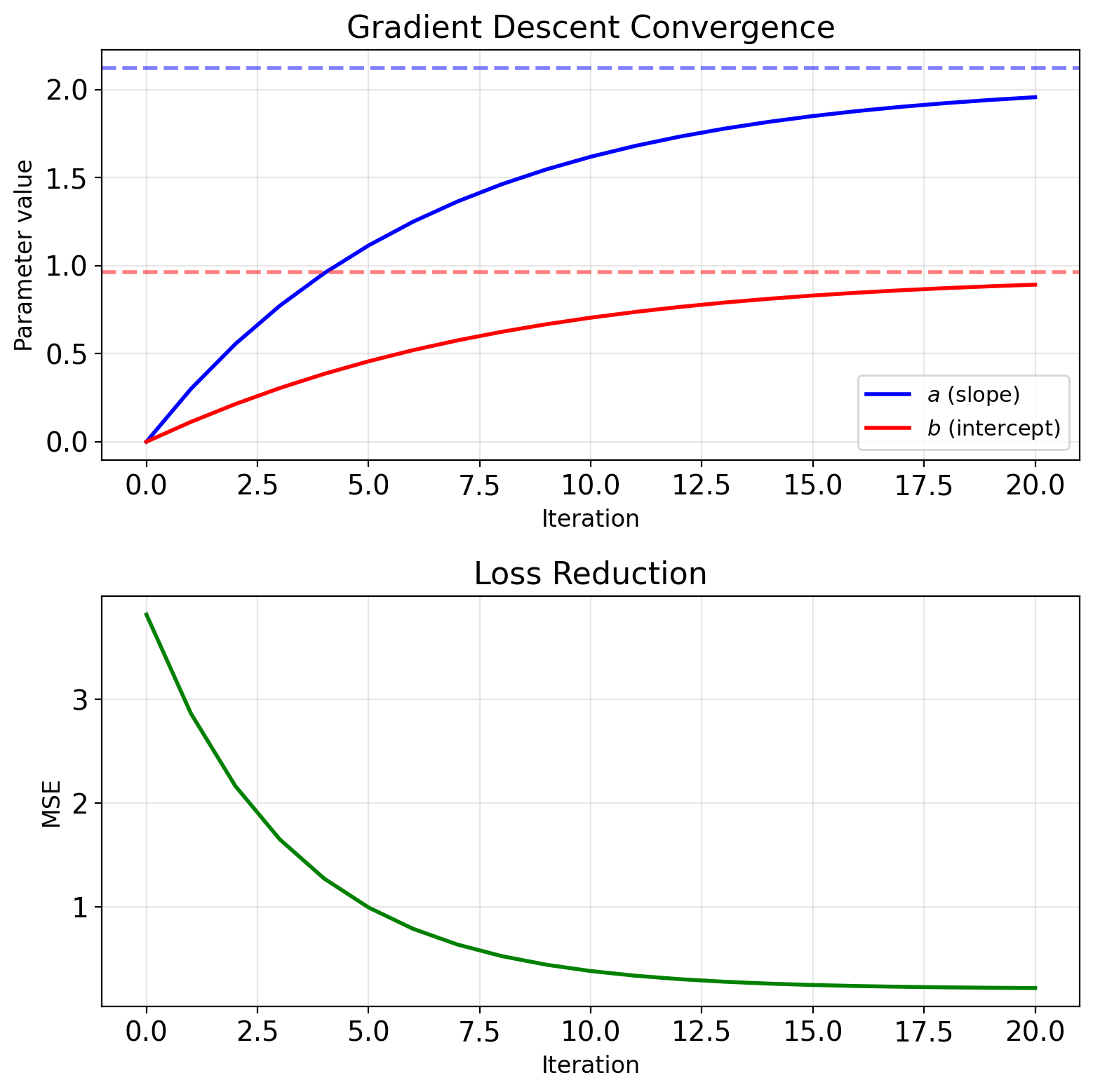

Gradient Descent Recovers LMMSE Iteratively

Batch gradient descent: \[J(a,b) = \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n (y_i - ax_i - b)^2\]

Gradients: \[\frac{\partial J}{\partial a} = -\frac{2}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n x_i(y_i - ax_i - b)\] \[\frac{\partial J}{\partial b} = -\frac{2}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n (y_i - ax_i - b)\]

Update: \[a_{t+1} = a_t - \eta \frac{\partial J}{\partial a}\] \[b_{t+1} = b_t - \eta \frac{\partial J}{\partial b}\]

Stochastic version (one sample): \[a_{t+1} = a_t + \eta x_i (y_i - a_t x_i - b_t)\] \[b_{t+1} = b_t + \eta (y_i - a_t x_i - b_t)\]

This is LMS algorithm (Widrow-Hoff)

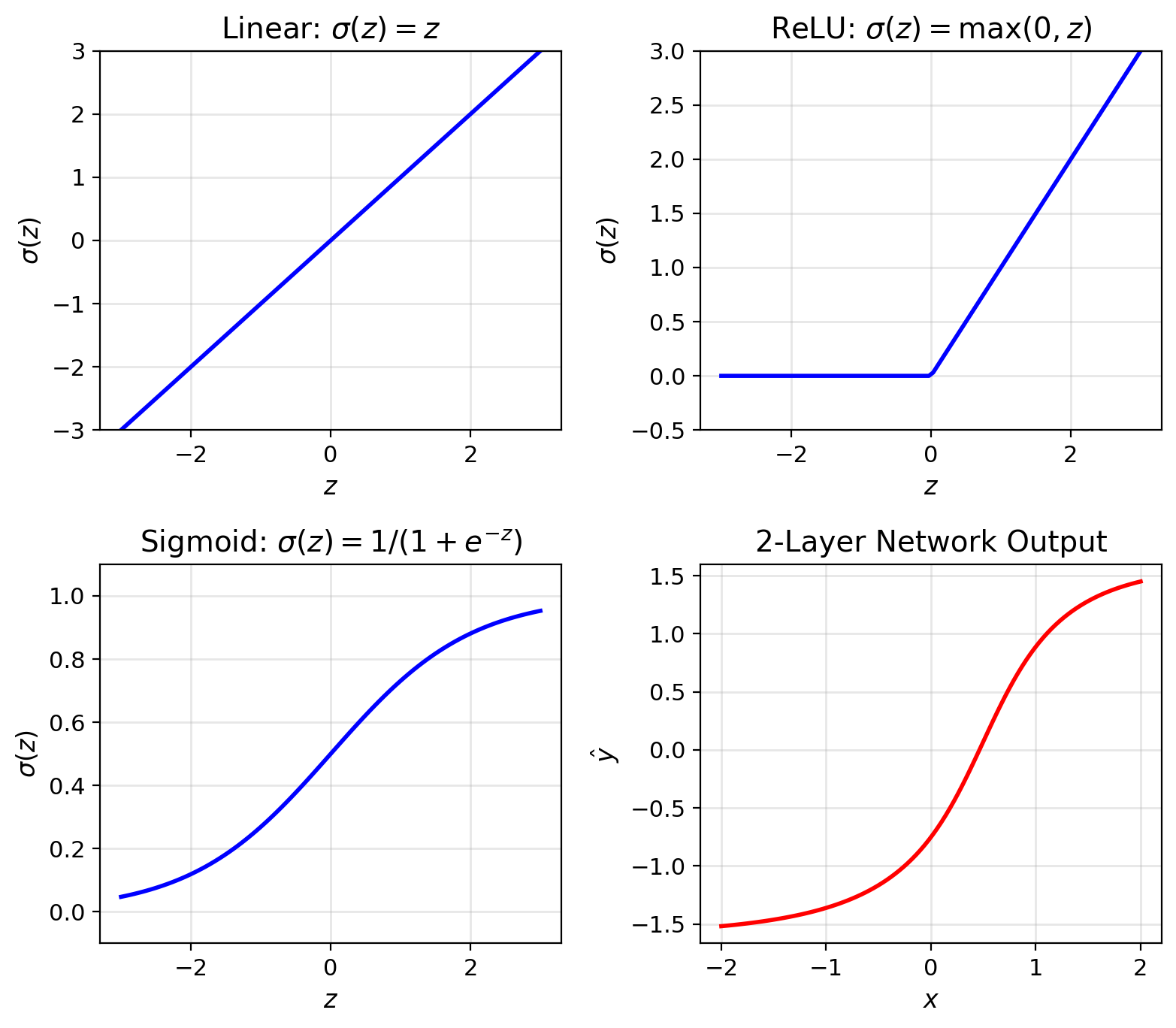

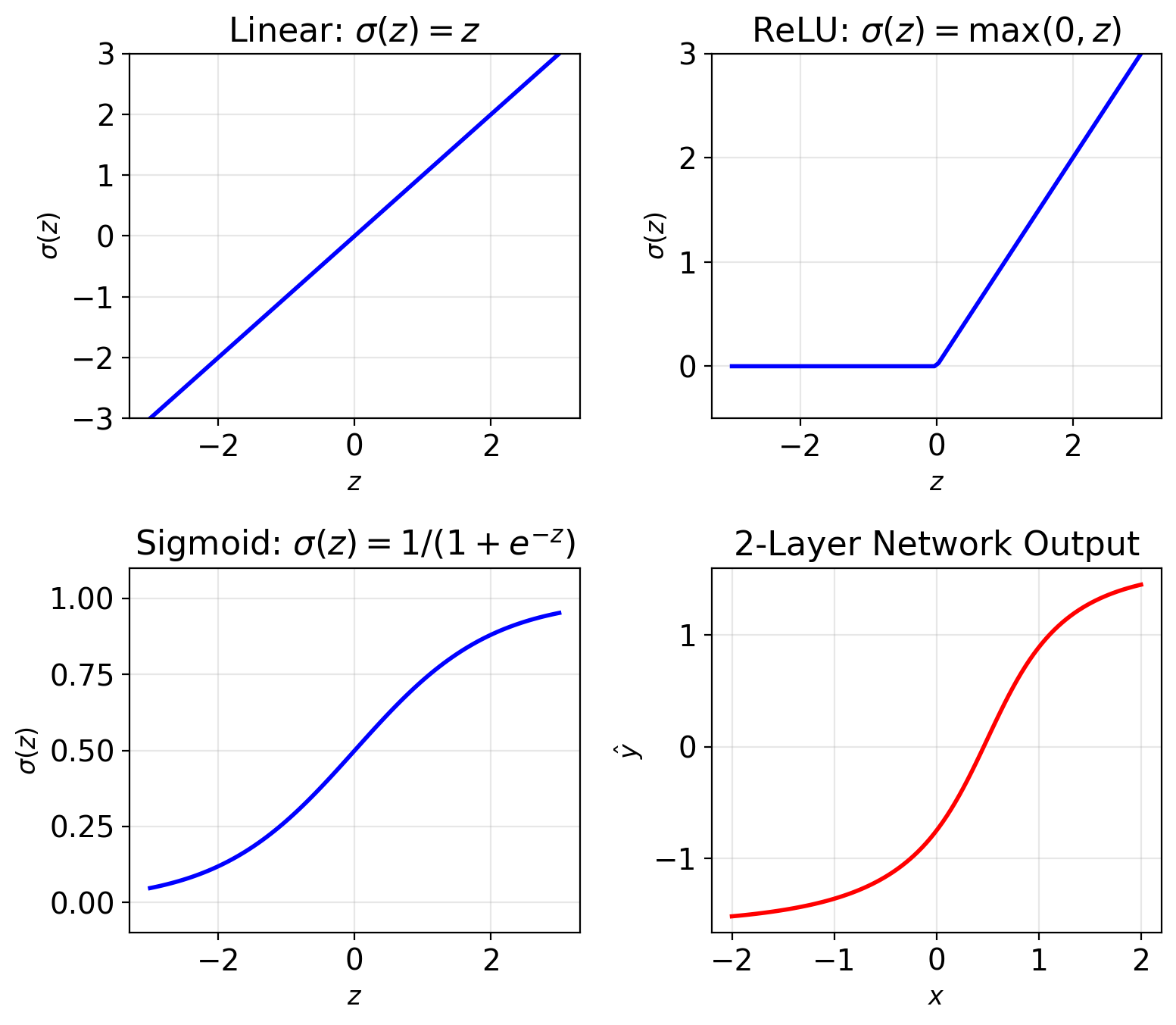

Networks Compose Linear Maps + Nonlinearities

LMMSE ≠ MMSE when \(\mathbb{E}[Y|X]\) is nonlinear.

Single neuron: \[z = \mathbf{w}^T\mathbf{x} + b\] \[h = \sigma(z)\]

where \(\sigma\) is activation (ReLU, sigmoid, etc.)

Without activation: Linear regression \[\hat{y} = \mathbf{w}^T\mathbf{x} + b\]

With activation: Nonlinear transform \[\hat{y} = \sigma(\mathbf{w}^T\mathbf{x} + b)\]

Deep network: Composition of layers \[\mathbf{h}^{(1)} = \sigma(W^{(1)}\mathbf{x} + \mathbf{b}^{(1)})\] \[\mathbf{h}^{(2)} = \sigma(W^{(2)}\mathbf{h}^{(1)} + \mathbf{b}^{(2)})\] \[\hat{y} = W^{(L)}\mathbf{h}^{(L-1)} + b^{(L)}\]

Objective: \(\frac{1}{n}\sum_i (y_i - \hat{y}_i)^2\) (same MSE)

Backpropagation: Chain rule for gradients

Multiple Predictors Require Matrix Operations

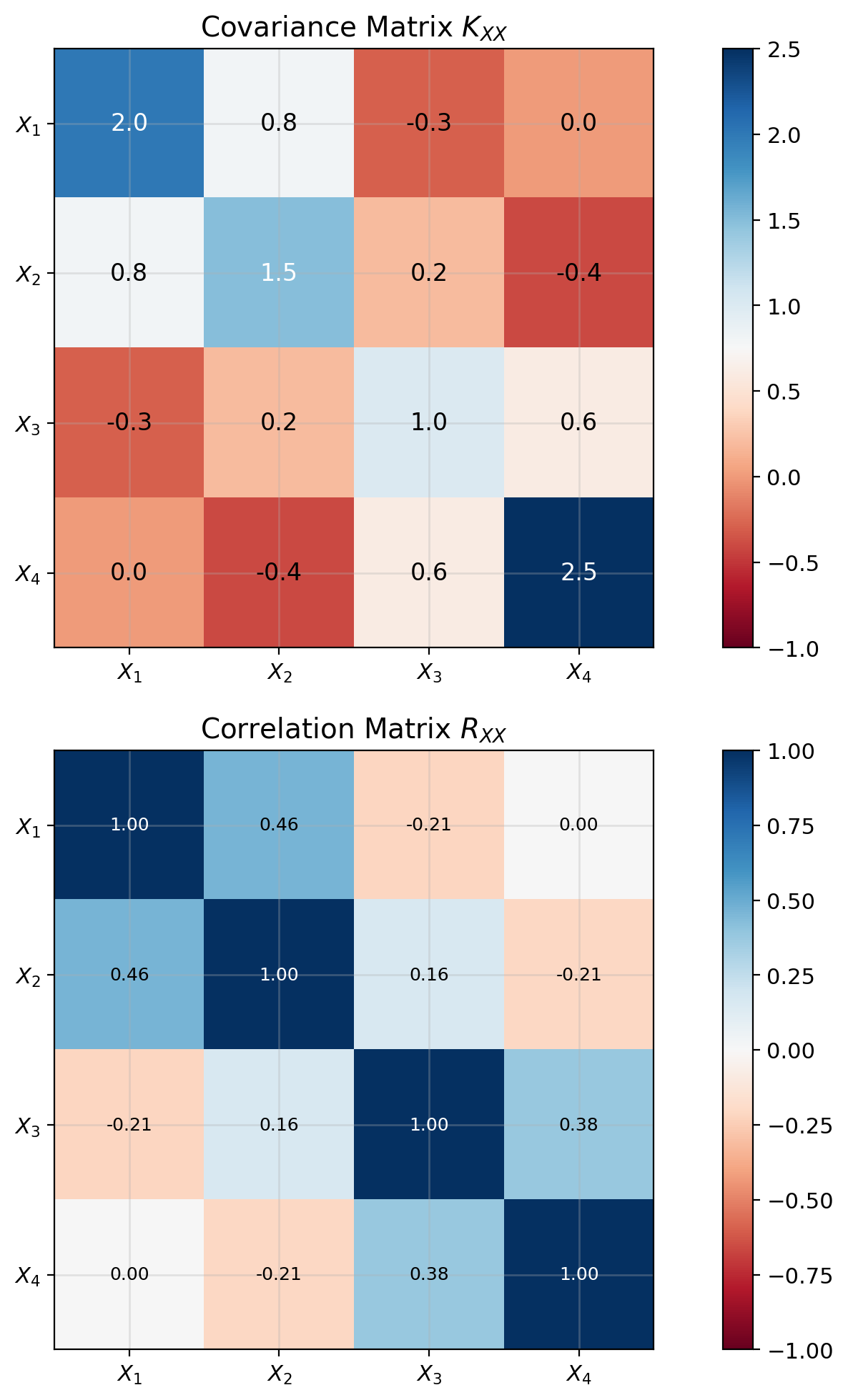

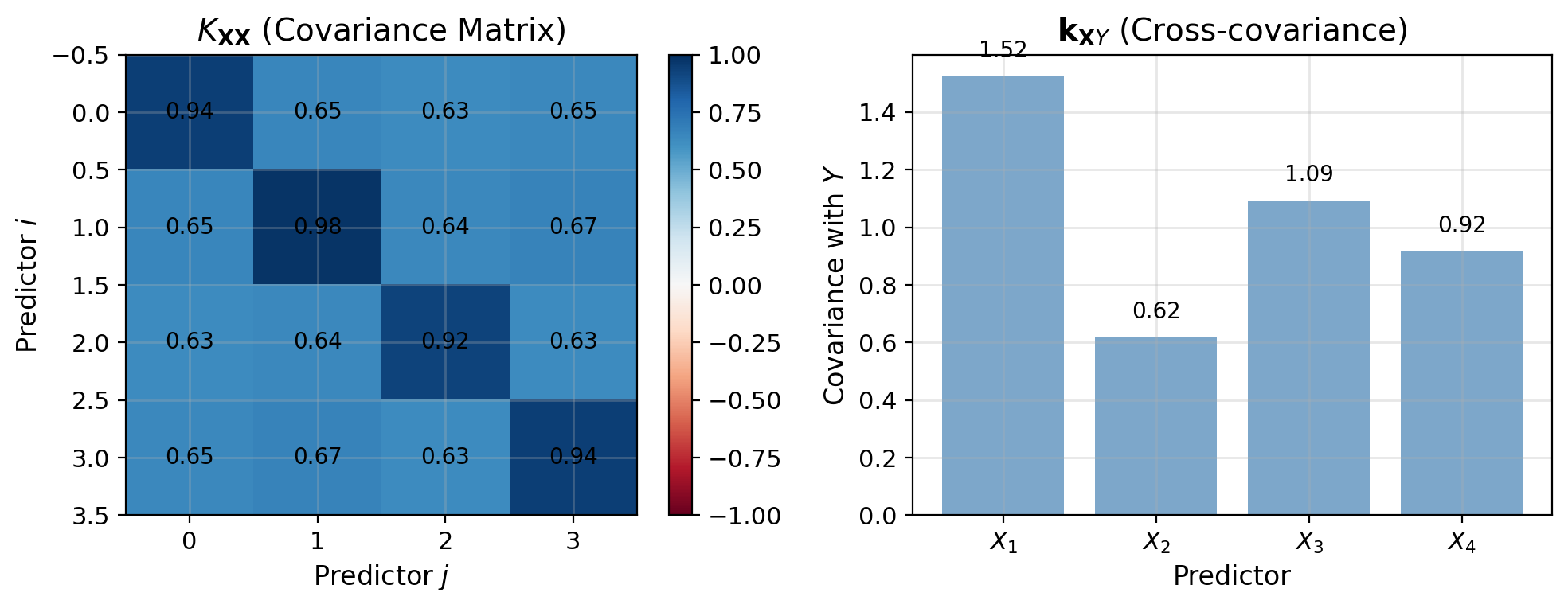

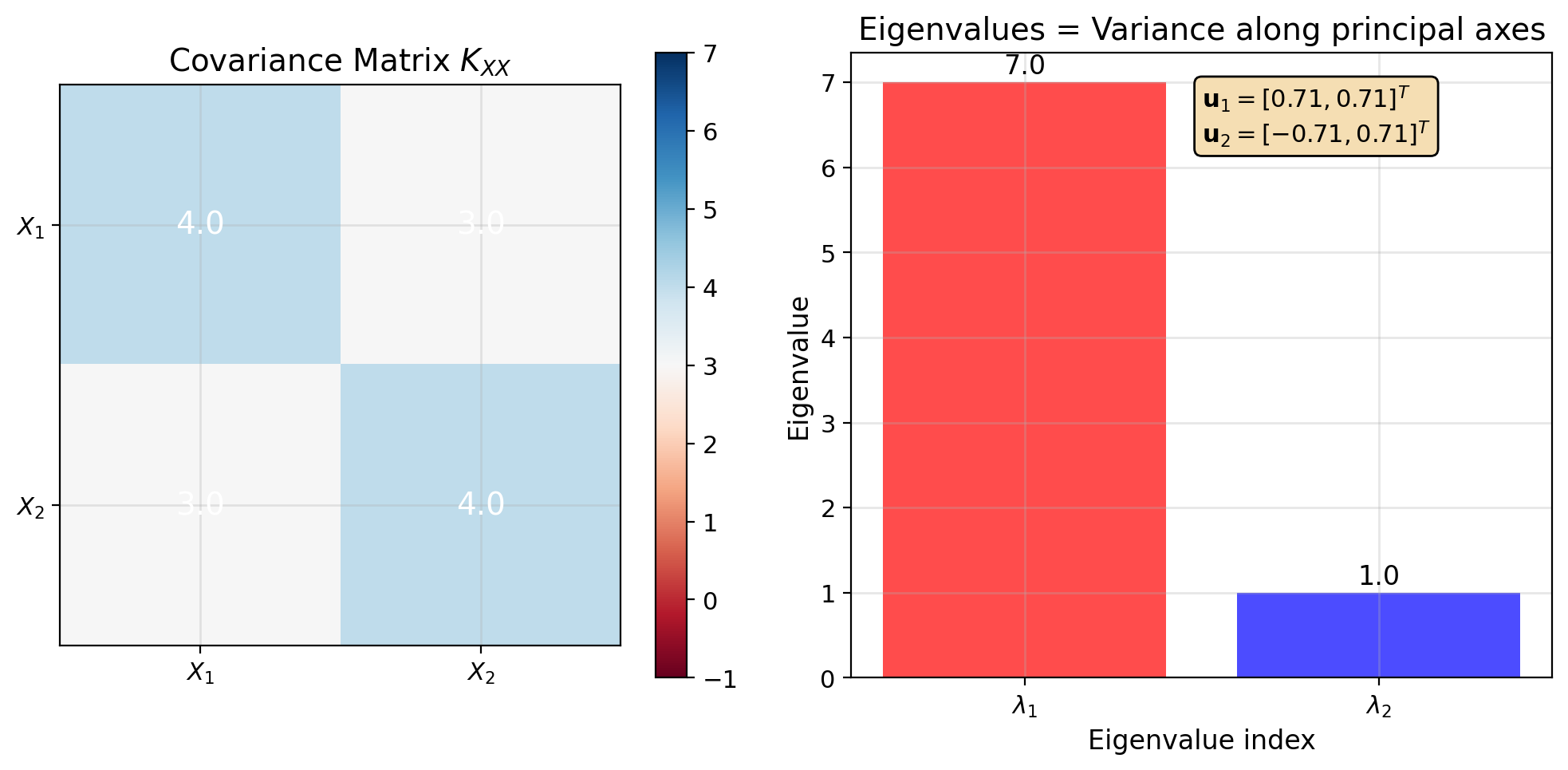

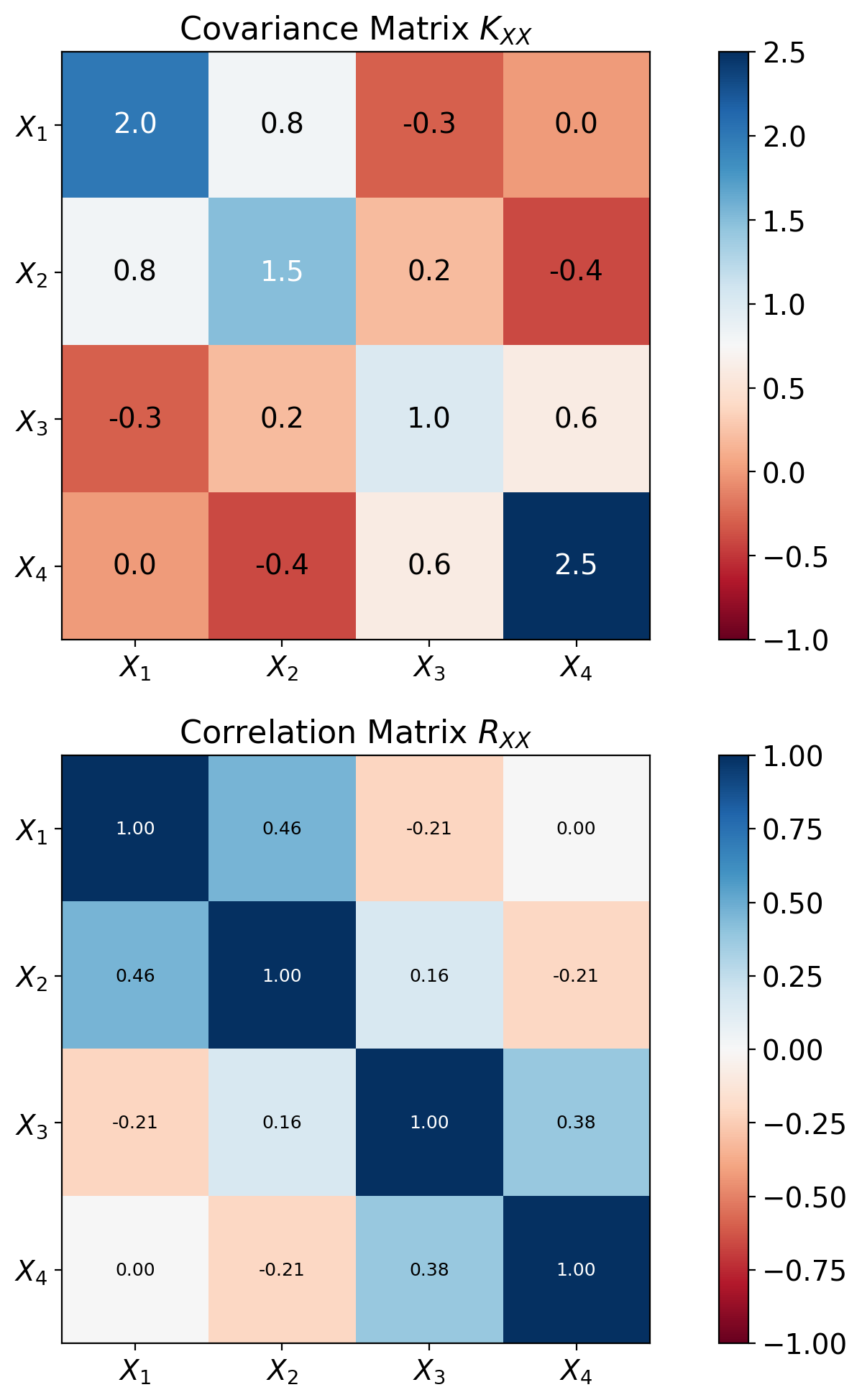

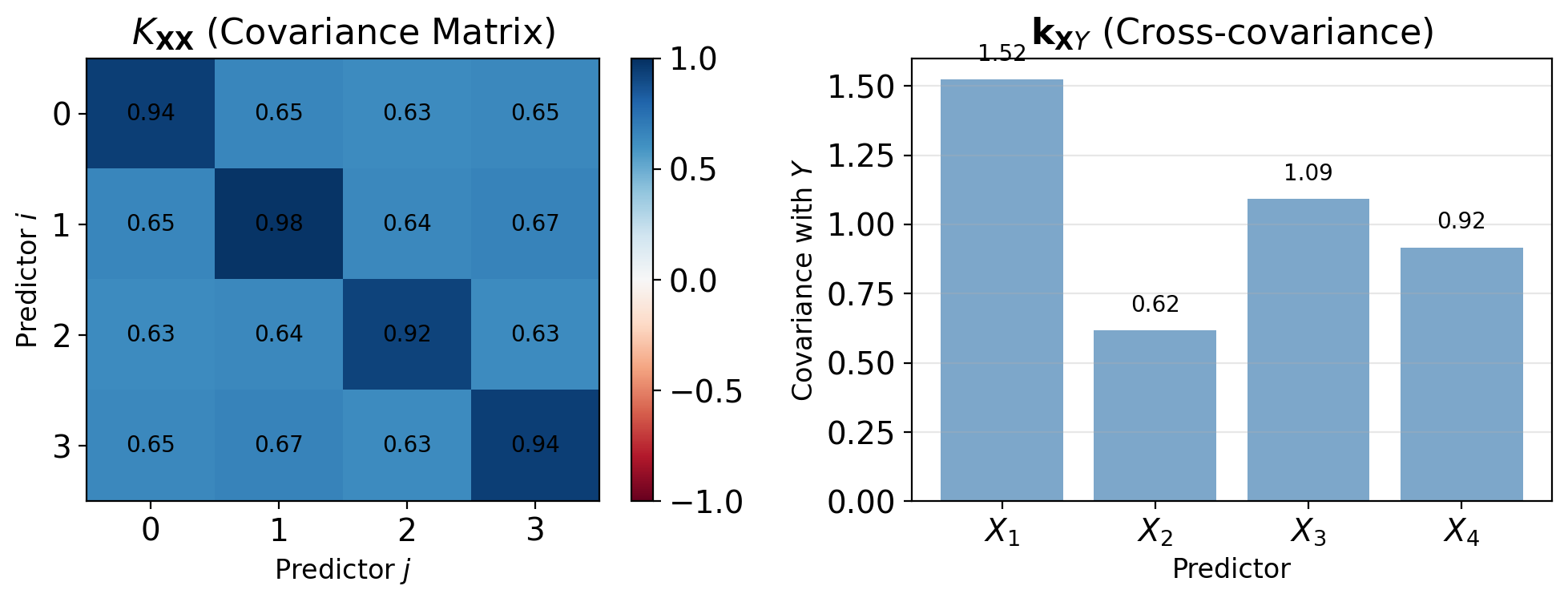

Covariance Matrices Encode Pairwise Relationships

Random vector: \(\mathbf{X} = [X_1, X_2, ..., X_n]^T\)

Mean vector: \[\boldsymbol{\mu} = \mathbb{E}[\mathbf{X}] = \begin{bmatrix} \mathbb{E}[X_1] \\ \mathbb{E}[X_2] \\ \vdots \\ \mathbb{E}[X_n] \end{bmatrix}\]

Covariance matrix: \[K_{\mathbf{XX}} = \mathbb{E}[(\mathbf{X} - \boldsymbol{\mu})(\mathbf{X} - \boldsymbol{\mu})^T]\]

Element structure: \[[K_{\mathbf{XX}}]_{ij} = \text{Cov}(X_i, X_j) = \mathbb{E}[(X_i - \mu_i)(X_j - \mu_j)]\]

Properties:

- Symmetric: \(K_{\mathbf{XX}} = K_{\mathbf{XX}}^T\)

- Positive semi-definite: \(\mathbf{a}^T K_{\mathbf{XX}} \mathbf{a} \geq 0\)

- Diagonal elements = variances

- Off-diagonal = covariances

Gaussian Vectors Are Closed Under Linear Transforms

Joint Gaussian distribution:

\(\begin{bmatrix} \mathbf{X} \\ \mathbf{Y} \end{bmatrix} \sim \mathcal{N}\left(\begin{bmatrix} \boldsymbol{\mu}_X \\ \boldsymbol{\mu}_Y \end{bmatrix}, \begin{bmatrix} K_{XX} & K_{XY} \\ K_{YX} & K_{YY} \end{bmatrix}\right)\)

Probability density: \[p(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y}) = \frac{1}{(2\pi)^{(n+m)/2}|K|^{1/2}} \exp\left(-\frac{1}{2}\mathbf{z}^TK^{-1}\mathbf{z}\right)\]

where \(\mathbf{z} = \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf{x} - \boldsymbol{\mu}_X \\ \mathbf{y} - \boldsymbol{\mu}_Y \end{bmatrix}\)

Linear operations preserve Gaussianity

If \(\mathbf{Z} = A\mathbf{X} + \mathbf{b}\), then: \[\mathbf{Z} \sim \mathcal{N}(A\boldsymbol{\mu}_X + \mathbf{b}, AK_{XX}A^T)\]

Marginals are Gaussian: \[\mathbf{X} \sim \mathcal{N}(\boldsymbol{\mu}_X, K_{XX})\]

Gaussian Conditional Mean Uses Schur Complement

Given joint Gaussian, conditional is also Gaussian:

\[\mathbf{X}|\mathbf{Y} = \mathbf{y} \sim \mathcal{N}(\boldsymbol{\mu}_{X|Y}, K_{X|Y})\]

Conditional mean (MMSE estimator): \[\boldsymbol{\mu}_{X|Y} = \boldsymbol{\mu}_X + K_{XY}K_{YY}^{-1}(\mathbf{y} - \boldsymbol{\mu}_Y)\]

Conditional covariance (error covariance): \[K_{X|Y} = K_{XX} - K_{XY}K_{YY}^{-1}K_{YX}\]

Observations:

- Conditional mean is linear in \(\mathbf{y}\)

- Conditional covariance doesn’t depend on \(\mathbf{y}\)

- For Gaussian: MMSE = Linear MMSE

Schur complement: \[K_{X|Y} = K_{XX} - K_{XY}K_{YY}^{-1}K_{YX}\] measures reduction in uncertainty

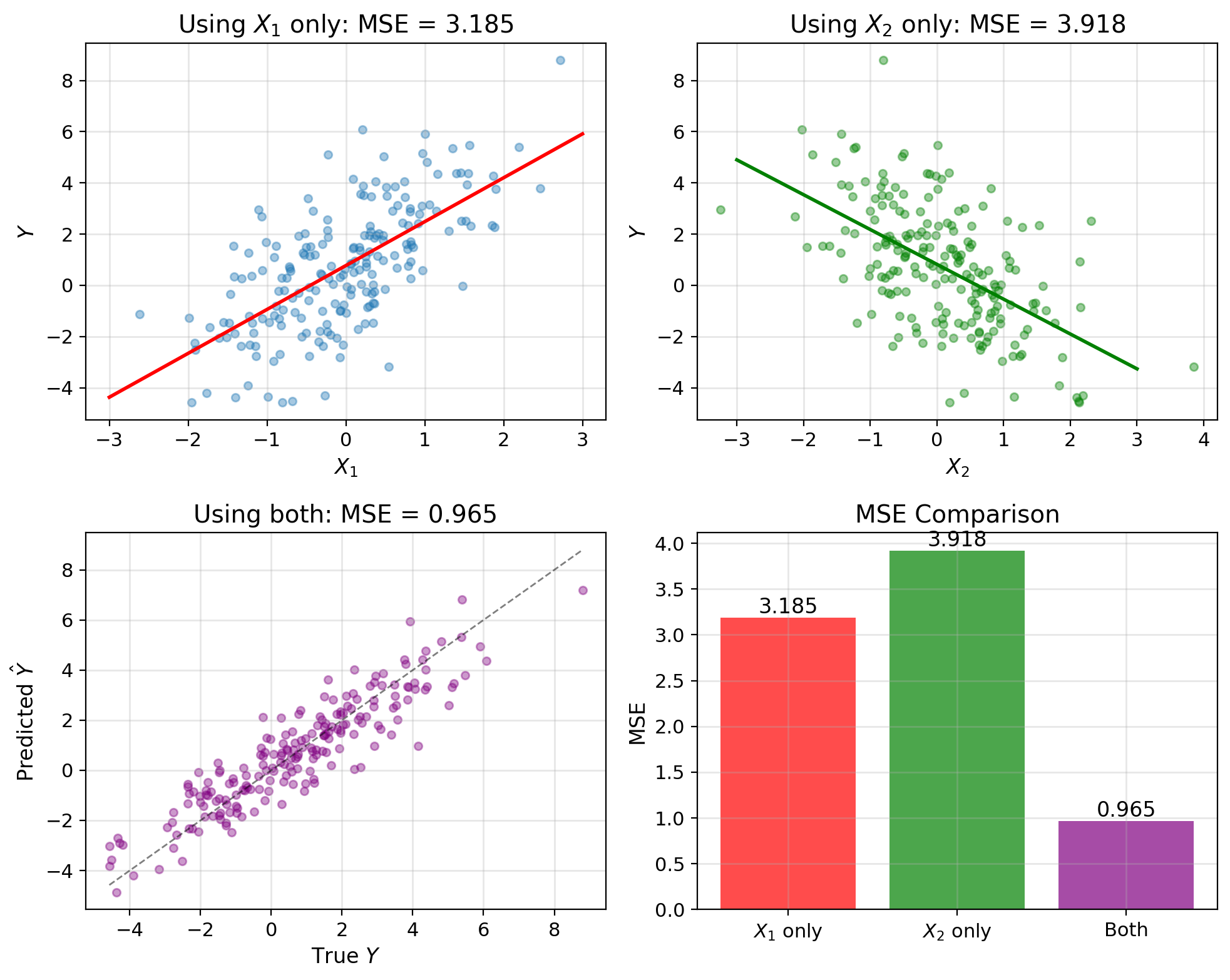

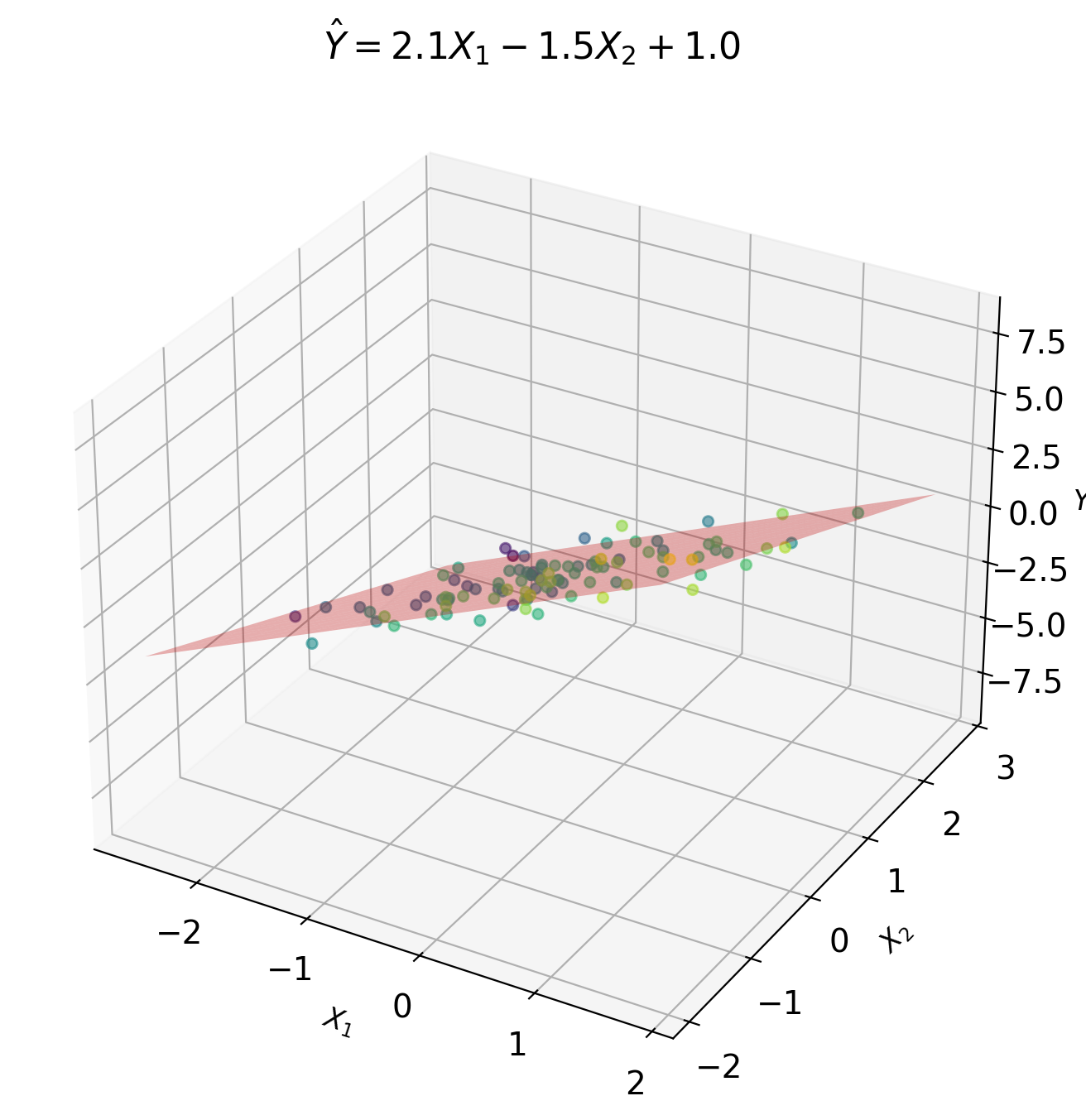

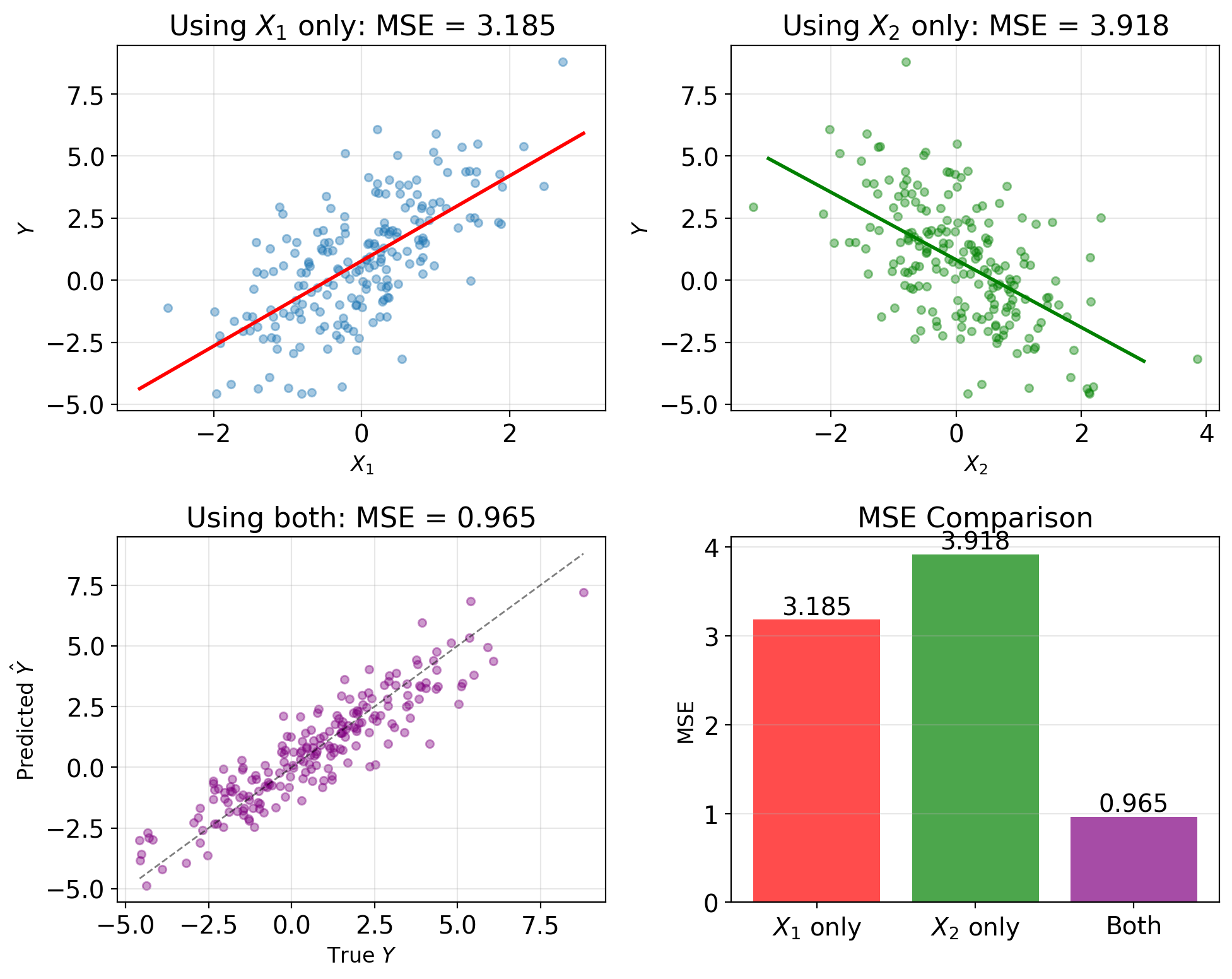

Combining Predictors Beats Any Single One

Scalar case: \[\hat{Y} = aX + b\]

Given: \(X\) (single predictor), predict \(Y\)

Vector case: \[\hat{Y} = \mathbf{a}^T\mathbf{X} + b\]

Given: \(\mathbf{X} = [X_1, X_2, ..., X_p]^T\) (multiple predictors)

Example: Predict temperature \(Y\) from:

- \(X_1\) = humidity sensor

- \(X_2\) = pressure sensor

- \(X_3\) = wind speed

Matrix notation: \[\hat{Y} = \mathbf{a}^T\mathbf{X} + b = \sum_{j=1}^p a_j X_j + b\]

where \(\mathbf{a} = [a_1, a_2, ..., a_p]^T\) are weights

Vector LMMSE Minimizes a Quadratic in a

Minimize MSE over linear predictors: \[\text{MSE}(\mathbf{a}, b) = \mathbb{E}[(Y - \mathbf{a}^T\mathbf{X} - b)^2]\]

Taking derivatives:

\[\frac{\partial \text{MSE}}{\partial b} = -2\mathbb{E}[Y - \mathbf{a}^T\mathbf{X} - b] = 0\] \[\implies b = \mathbb{E}[Y] - \mathbf{a}^T\mathbb{E}[\mathbf{X}]\]

\[\frac{\partial \text{MSE}}{\partial \mathbf{a}} = -2\mathbb{E}[\mathbf{X}(Y - \mathbf{a}^T\mathbf{X} - b)] = \mathbf{0}\]

Substituting \(b\) and simplifying: \[\mathbb{E}[\mathbf{X}\mathbf{X}^T]\mathbf{a} = \mathbb{E}[\mathbf{X}Y] - \mathbb{E}[\mathbf{X}]\mathbb{E}[Y]\]

Define:

- \(K_{\mathbf{XX}} = \mathbb{E}[\mathbf{X}\mathbf{X}^T] - \mathbb{E}[\mathbf{X}]\mathbb{E}[\mathbf{X}]^T\) (covariance matrix)

- \(\mathbf{k}_{\mathbf{X}Y} = \mathbb{E}[\mathbf{X}Y] - \mathbb{E}[\mathbf{X}]\mathbb{E}[Y]\) (cross-covariance vector)

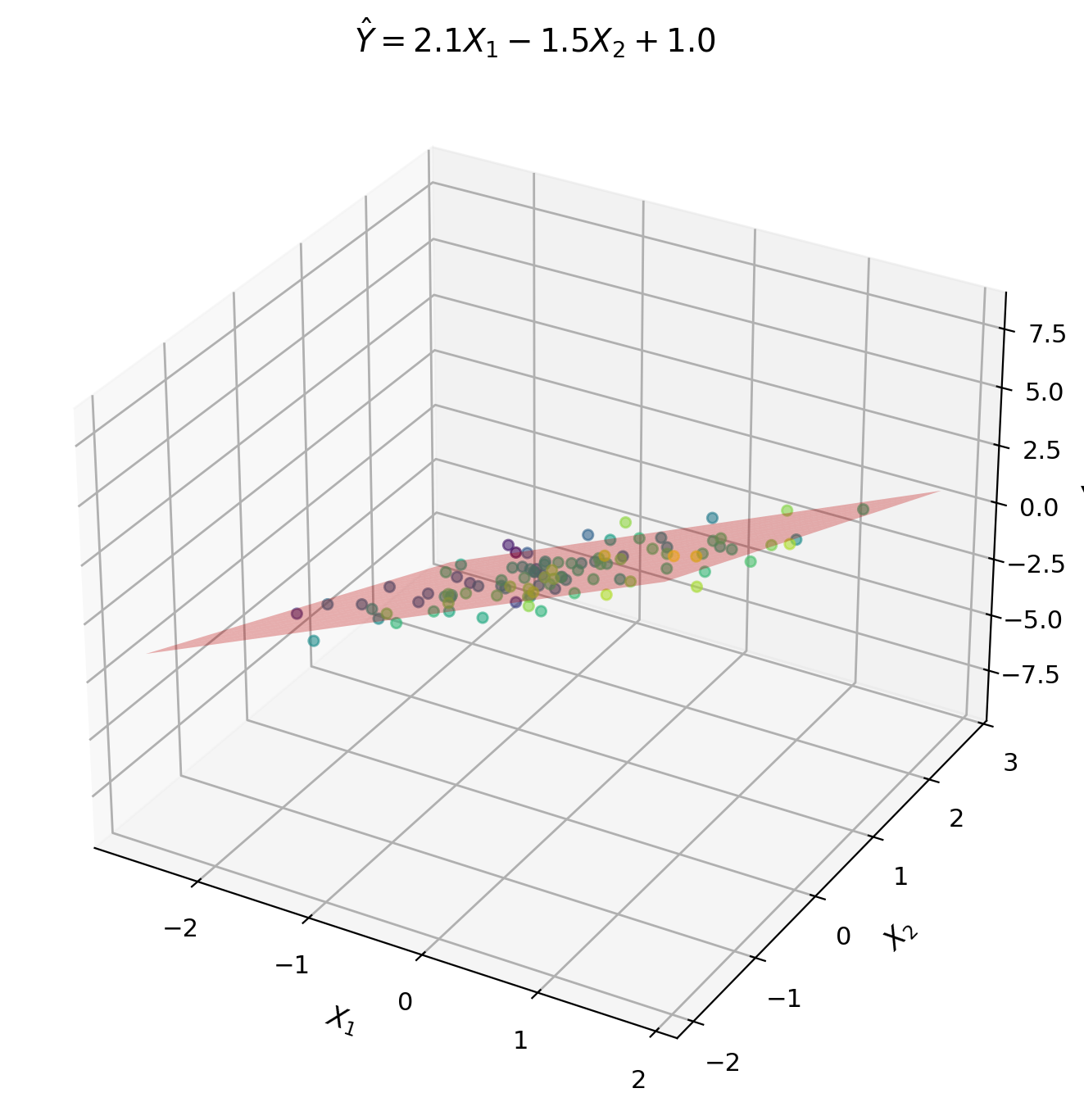

Normal Equations: K_XX a = k_XY

Normal equations: \[K_{\mathbf{XX}}\mathbf{a} = \mathbf{k}_{\mathbf{X}Y}\]

Solution (if \(K_{\mathbf{XX}}\) invertible): \[\mathbf{a}^* = K_{\mathbf{XX}}^{-1}\mathbf{k}_{\mathbf{X}Y}\] \[b^* = \mathbb{E}[Y] - (\mathbf{a}^*)^T\mathbb{E}[\mathbf{X}]\]

LMMSE predictor: \[\hat{Y}_{\text{LMMSE}} = \mathbb{E}[Y] + (\mathbf{a}^*)^T(\mathbf{X} - \mathbb{E}[\mathbf{X}])\]

Minimum MSE: \[\text{MSE}_{\min} = \text{Var}(Y) - \mathbf{k}_{\mathbf{X}Y}^T K_{\mathbf{XX}}^{-1} \mathbf{k}_{\mathbf{X}Y}\]

Describes:

- Variance reduction = \(\mathbf{k}_{\mathbf{X}Y}^T K_{\mathbf{XX}}^{-1} \mathbf{k}_{\mathbf{X}Y}\)

- Measures how much \(\mathbf{X}\) helps predict \(Y\)

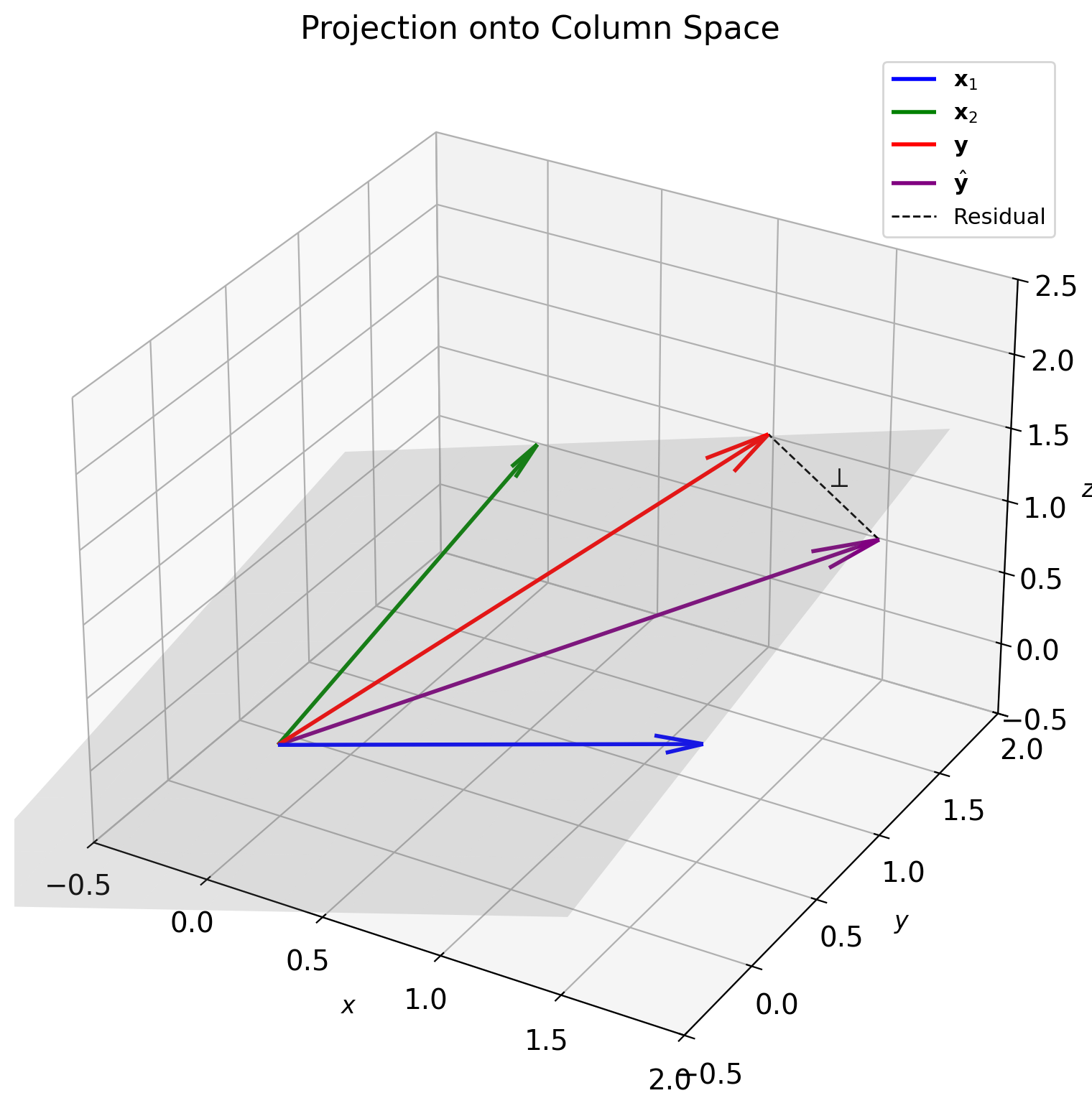

LMMSE = Projection onto Column Space

Column space perspective:

Data matrix columns: \(\mathbf{x}_1, \mathbf{x}_2, ..., \mathbf{x}_p\)

\[\mathcal{S} = \text{span}(\mathbf{x}_1, \mathbf{x}_2, ..., \mathbf{x}_p)\]

LMMSE = Projection: \[\hat{\mathbf{y}} = \text{Proj}_{\mathcal{S}}(\mathbf{y})\]

Orthogonality: \[\mathbf{y} - \hat{\mathbf{y}} \perp \mathcal{S}\]

Equivalently: \(X^T(\mathbf{y} - X\mathbf{a}) = \mathbf{0}\)

Projection matrix: \[P = X(X^TX)^{-1}X^T\] \[\hat{\mathbf{y}} = P\mathbf{y}\]

Properties:

- \(P^2 = P\) (idempotent)

- \(P^T = P\) (symmetric)

- \(\text{rank}(P) = p\) (dimension of \(\mathcal{S}\))

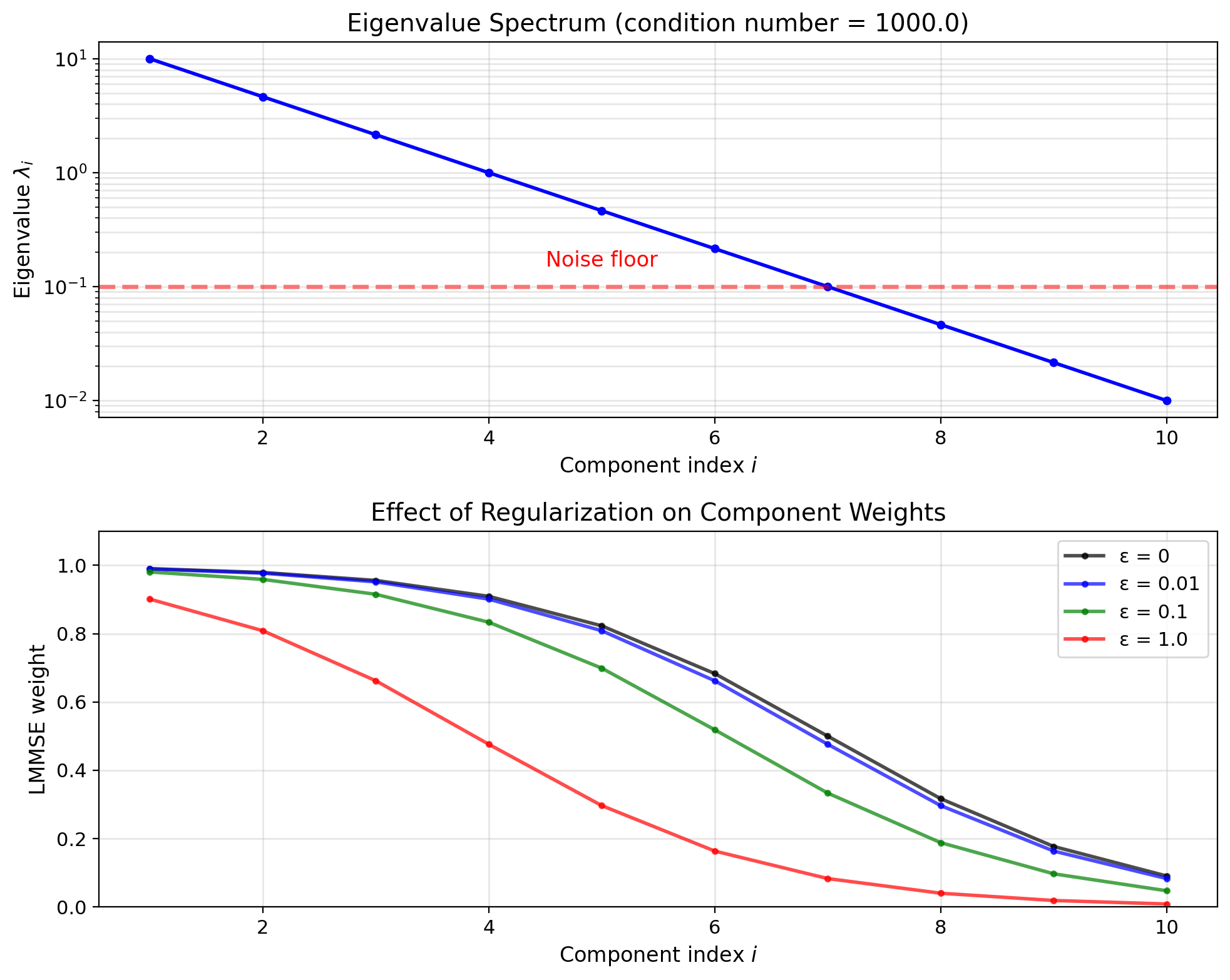

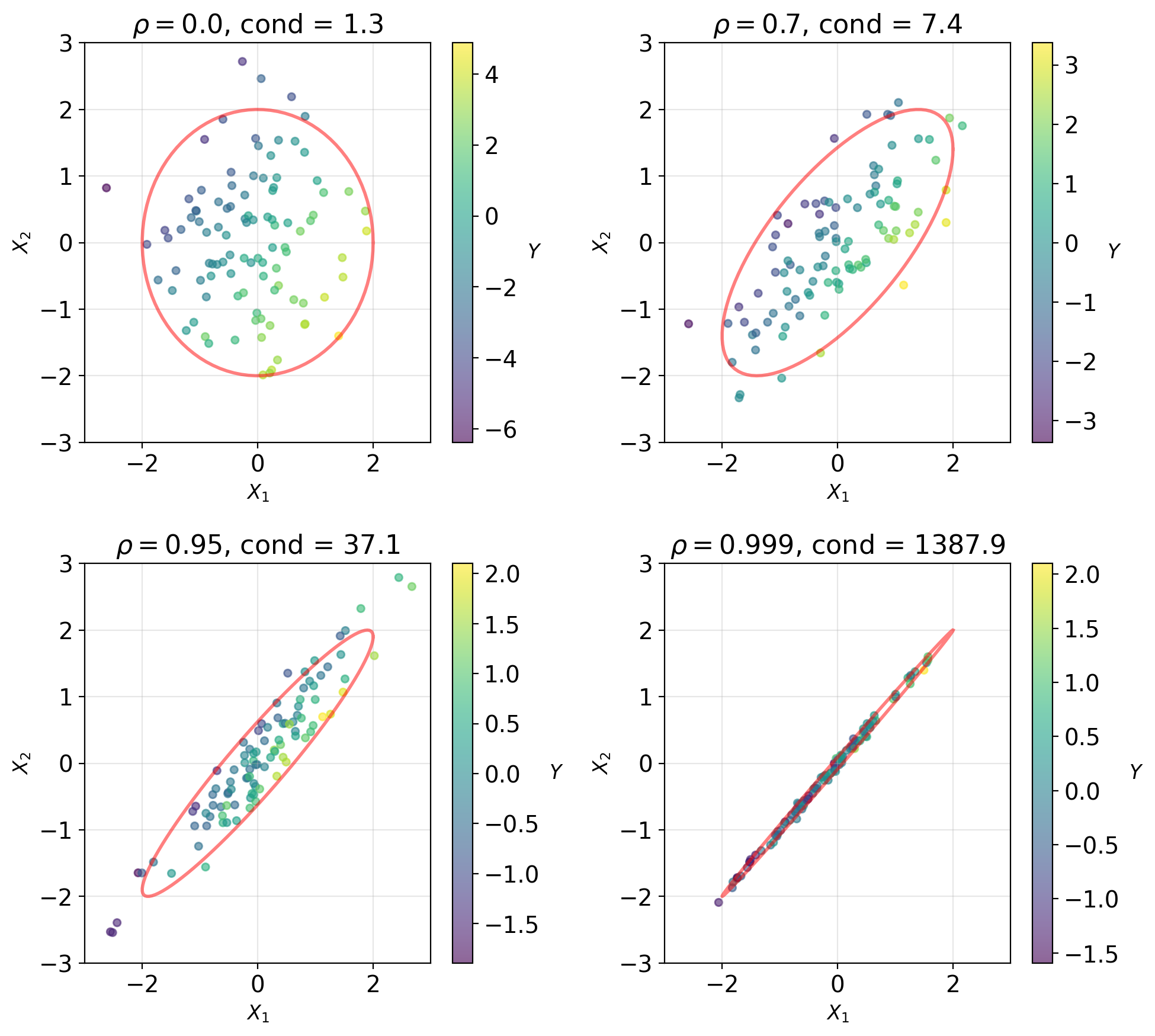

Collinearity Makes K_XX Ill-Conditioned

Direct inversion issues:

Ill-conditioning: When predictors highly correlated

- \(\text{cond}(K_{\mathbf{XX}}) = \frac{\lambda_{\max}}{\lambda_{\min}} \gg 1\)

- Small changes → large parameter changes

Rank deficiency: When \(p > n\) or perfect collinearity

- \(K_{\mathbf{XX}}\) not invertible

- Infinitely many solutions

Solutions:

QR decomposition: \(X = QR\)

- More stable than normal equations

- \(\mathbf{a} = R^{-1}Q^T\mathbf{y}\)

SVD: \(X = U\Sigma V^T\)

- Handles rank-deficient cases

- Pseudoinverse: \(X^+ = V\Sigma^+ U^T\)

Regularization:

- Ridge: Add \(\lambda I\) to \(K_{\mathbf{XX}}\)

- Makes problem well-posed

- Trades bias for stability

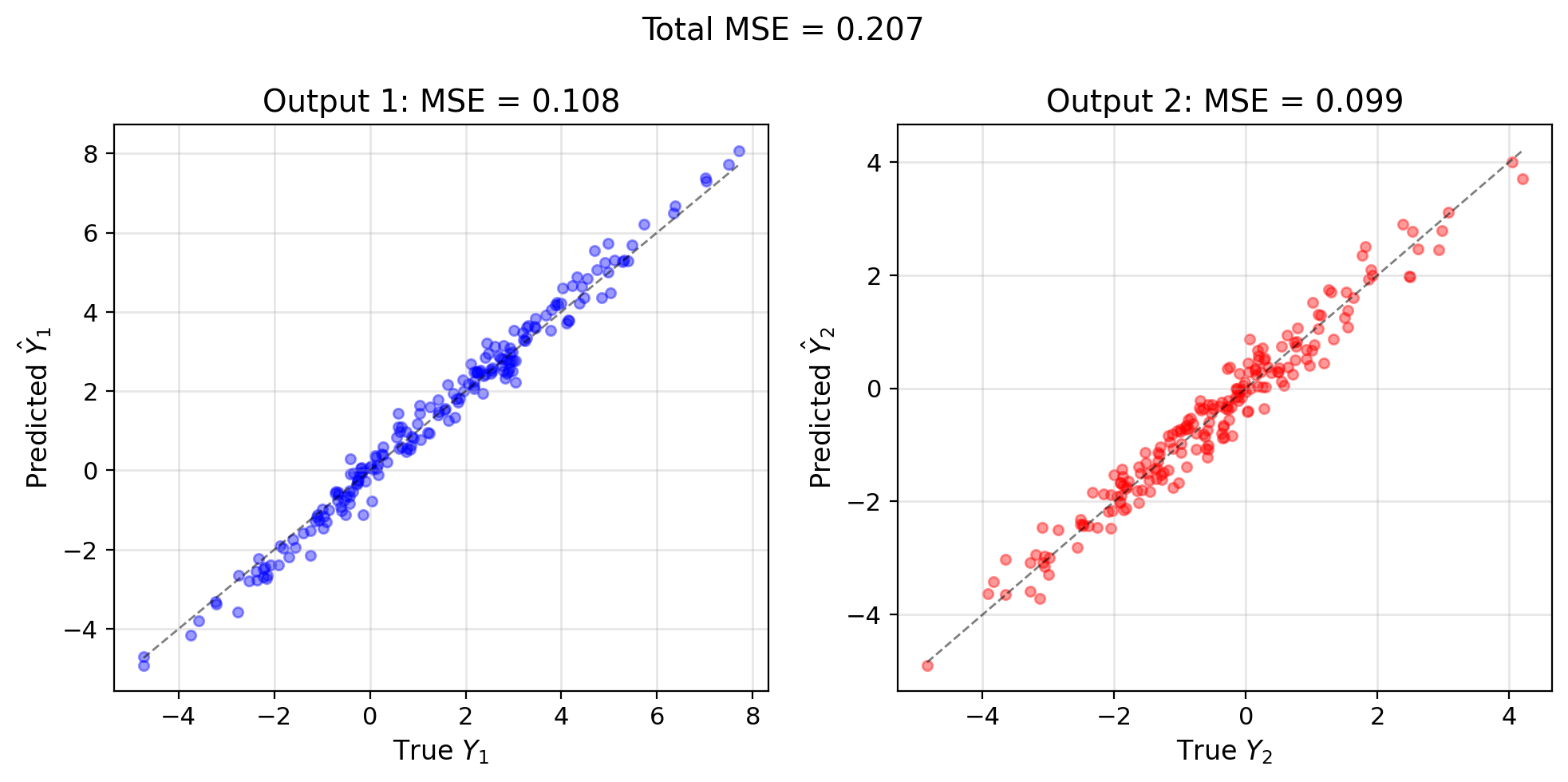

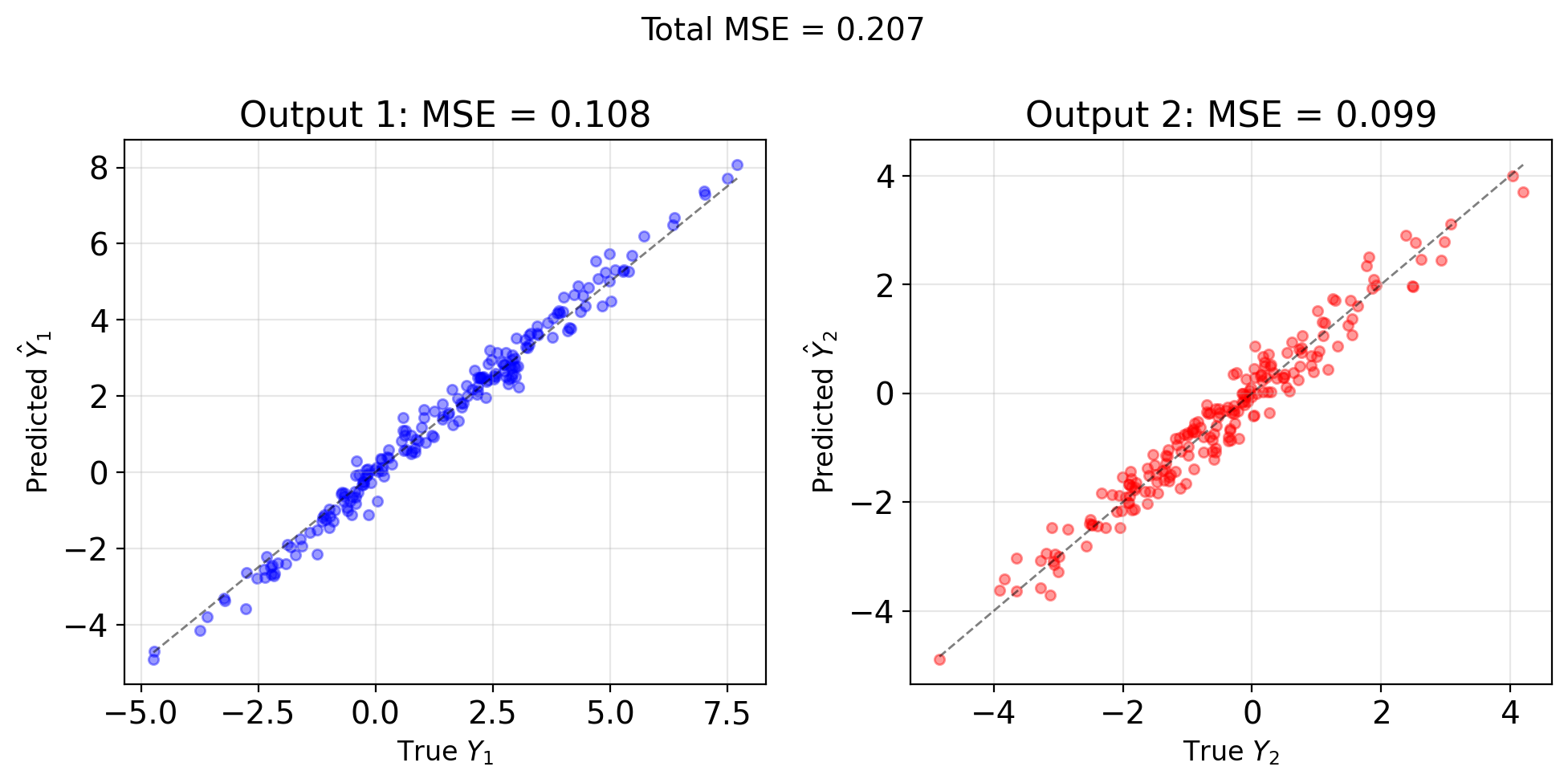

Multiple Outputs Decompose into Scalar Problems

Multiple responses: \[\mathbf{Y} = [Y_1, Y_2, ..., Y_m]^T\]

Linear model: \[\hat{\mathbf{Y}} = W^T\mathbf{X} + \mathbf{b}\]

where \(W \in \mathbb{R}^{p \times m}\) is weight matrix

MSE matrix: \[\mathbf{M} = \mathbb{E}[(\mathbf{Y} - \hat{\mathbf{Y}})(\mathbf{Y} - \hat{\mathbf{Y}})^T]\]

Minimize trace (total MSE): \[\text{tr}(\mathbf{M}) = \sum_{i=1}^m \mathbb{E}[(Y_i - \hat{Y}_i)^2]\]

Solution: \[W^* = K_{\mathbf{XX}}^{-1}K_{\mathbf{XY}}\]

where \(K_{\mathbf{XY}} = \mathbb{E}[\mathbf{X}\mathbf{Y}^T] - \mathbb{E}[\mathbf{X}]\mathbb{E}[\mathbf{Y}]^T\)

Key: Solve \(m\) separate LMMSE problems

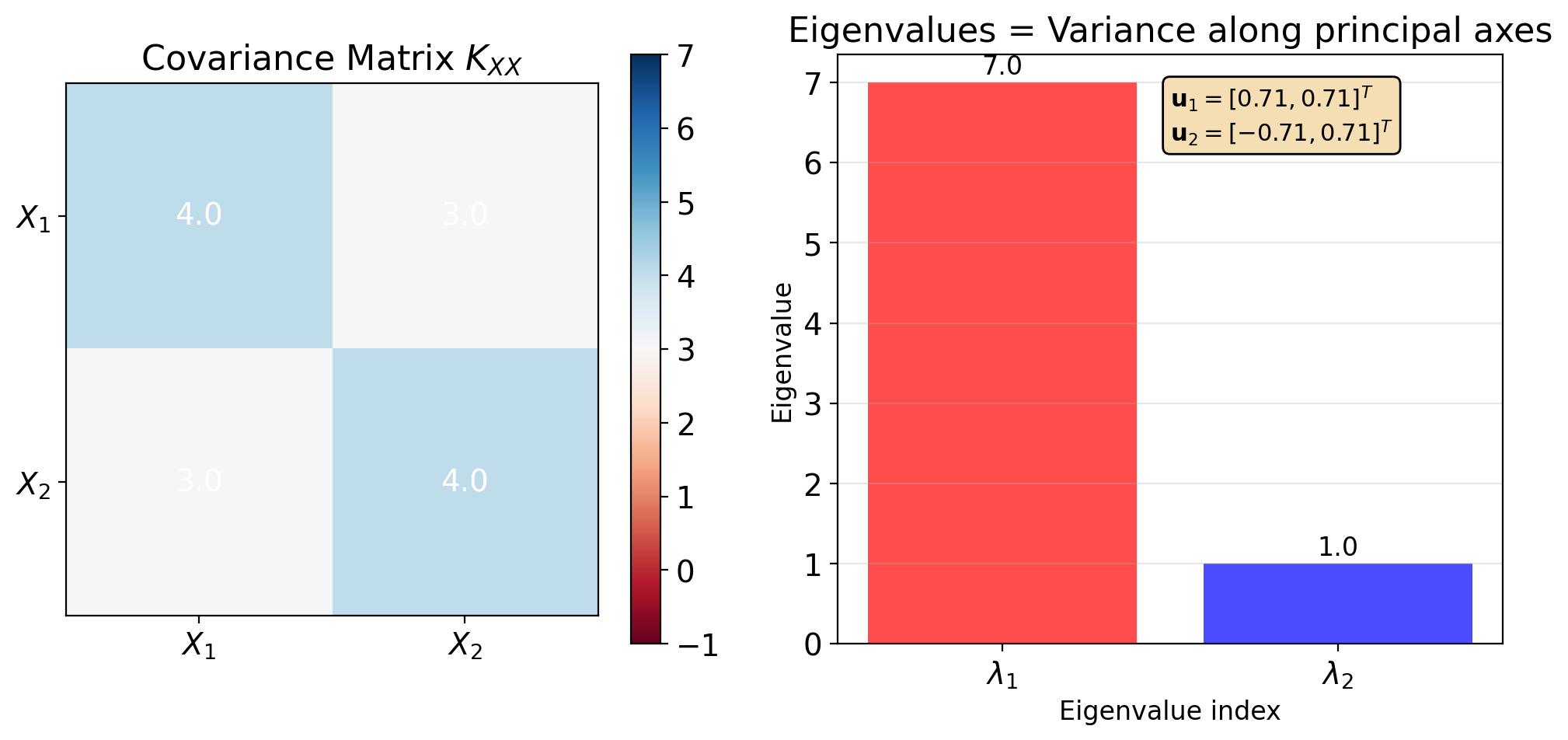

Eigendecomposition Diagonalizes the Covariance

Computational cost:

When \(K_{\mathbf{XX}}\) has off-diagonal terms:

- Matrix inversion requires \(O(p^3)\) operations

- All variables coupled in solution

- Numerical instability for ill-conditioned matrices

Eigendecomposition approach:

Any symmetric positive semi-definite matrix: \[K_{\mathbf{XX}} = U\Lambda U^T\]

where:

- \(U = [\mathbf{u}_1, \mathbf{u}_2, ..., \mathbf{u}_p]\) orthonormal

- \(\Lambda = \text{diag}(\lambda_1, \lambda_2, ..., \lambda_p)\)

- \(\lambda_1 \geq \lambda_2 \geq ... \geq \lambda_p \geq 0\)

Eigenvectors are orthogonal \[\mathbf{u}_i^T \mathbf{u}_j = \delta_{ij}\]

This orthogonality simplifies coordinate transformation.

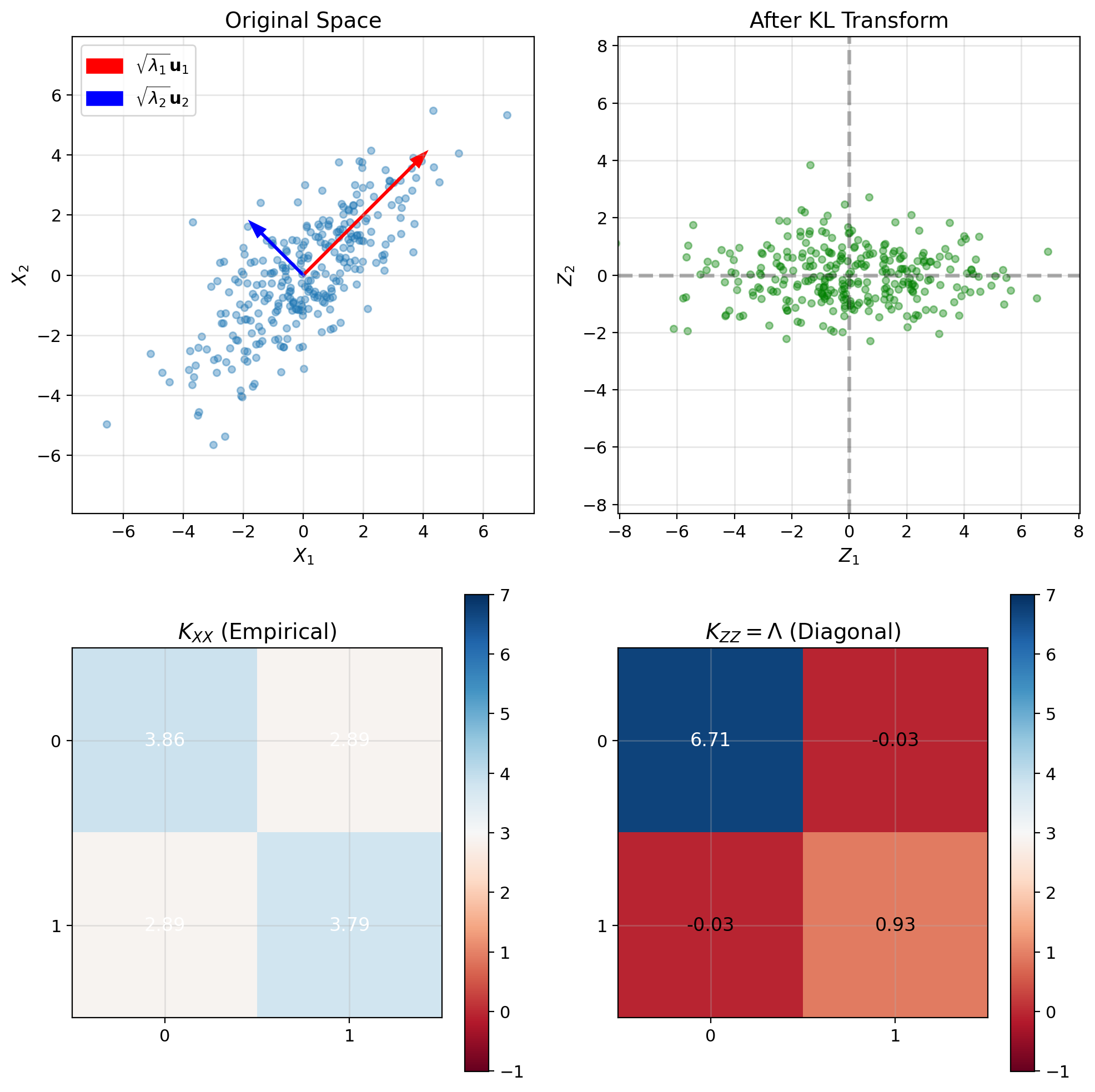

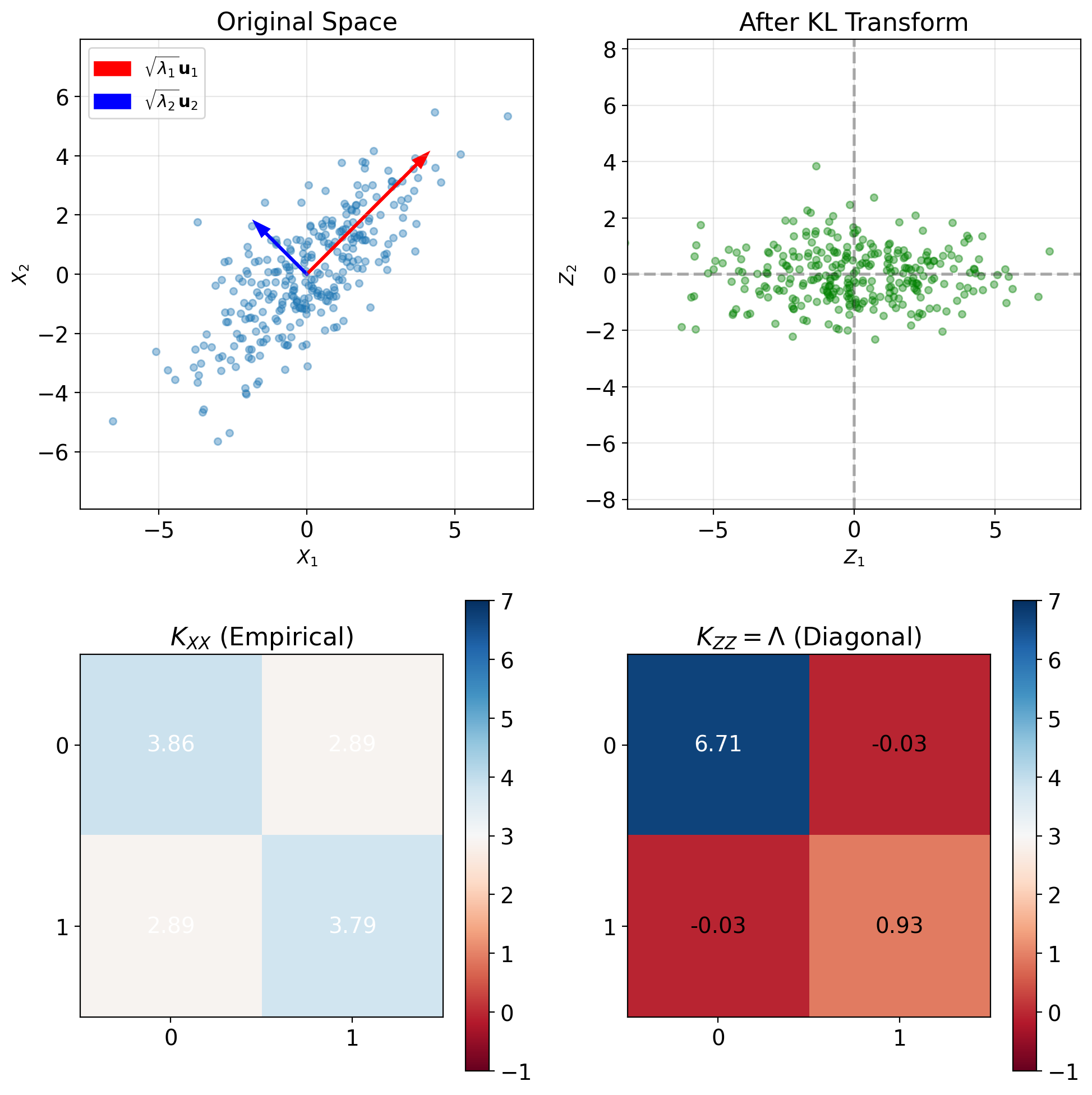

KL Transform Produces Uncorrelated Components

Coordinate transformation: \[\mathbf{Z} = U^T\mathbf{X}\]

Covariance in new coordinates: \[K_{\mathbf{ZZ}} = \mathbb{E}[\mathbf{Z}\mathbf{Z}^T]\] \[= \mathbb{E}[U^T\mathbf{X}\mathbf{X}^TU]\] \[= U^T\mathbb{E}[\mathbf{X}\mathbf{X}^T]U\] \[= U^TK_{\mathbf{XX}}U\] \[= U^T(U\Lambda U^T)U\] \[= \Lambda\]

Result: Diagonal covariance matrix

Components of \(\mathbf{Z}\) are uncorrelated: \[\mathbb{E}[Z_iZ_j] = \lambda_i\delta_{ij}\]

Inverse transform (reconstruction): \[\mathbf{X} = U\mathbf{Z}\]

Since \(U\) is orthonormal: \(U^TU = I\)

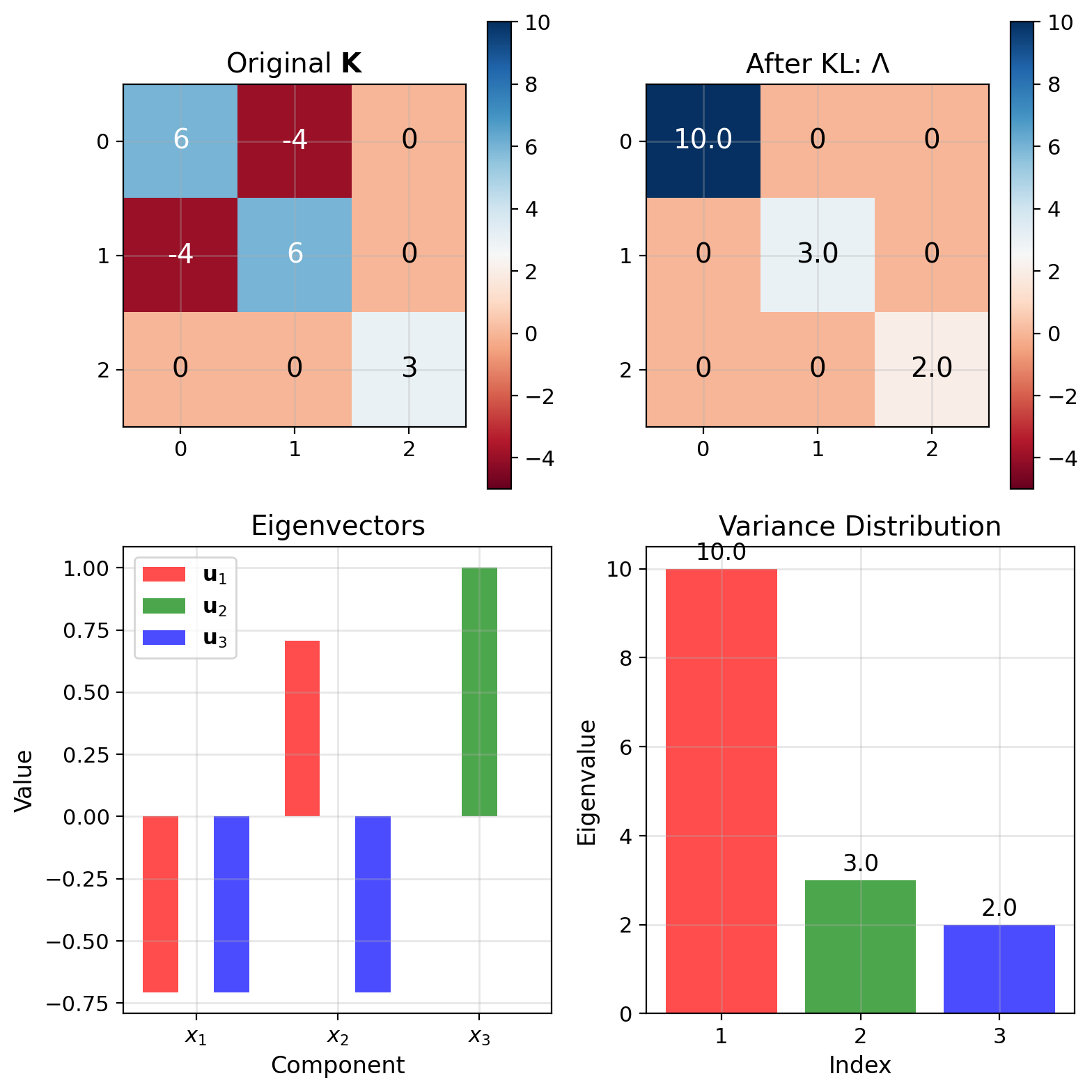

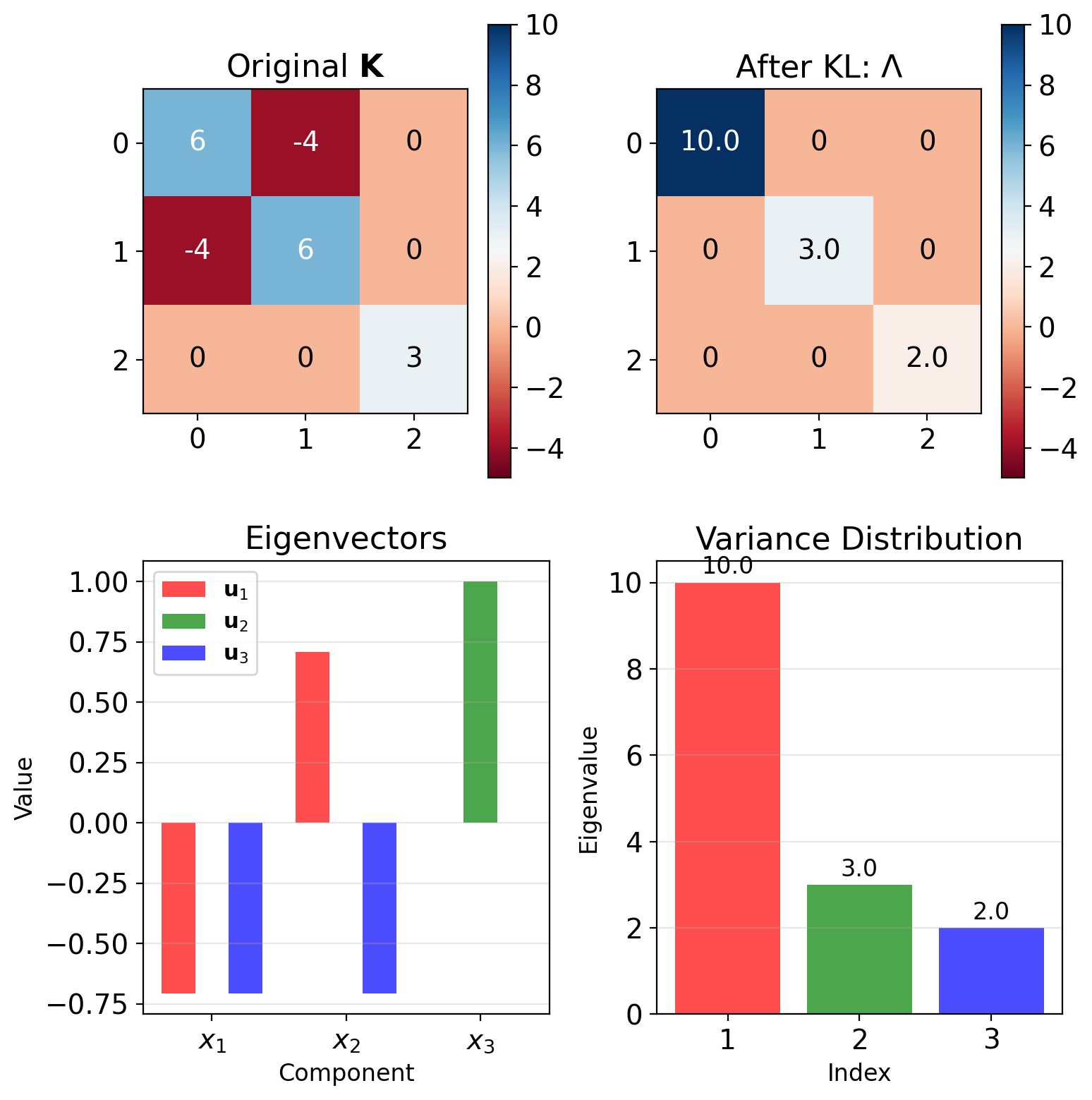

Worked Example: Diagonalizing a 3×3 Covariance

Given covariance: \[\mathbf{K} = \begin{bmatrix} 6 & -4 & 0 \\ -4 & 6 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 3 \end{bmatrix}\]

Find eigenvalues: Solve \(\det(\mathbf{K} - \lambda\mathbf{I}) = 0\)

Block structure simplifies:

- Upper 2×2 block: \(\lambda_{1,2} = 6 \pm 4\)

- Lower 1×1 block: \(\lambda_3 = 3\)

Result: \(\lambda_1 = 10, \lambda_2 = 3, \lambda_3 = 2\)

Find eigenvectors: Solve \((\mathbf{K} - \lambda_i\mathbf{I})\mathbf{v} = 0\)

\[\mathbf{u}_1 = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\begin{bmatrix}1\\-1\\0\end{bmatrix}, \quad \mathbf{u}_2 = \begin{bmatrix}0\\0\\1\end{bmatrix}, \quad \mathbf{u}_3 = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\begin{bmatrix}1\\1\\0\end{bmatrix}\]

Result: \(\mathbf{K}_{zz} = \text{diag}(10, 3, 2)\)

Decorrelated Coordinates Decouple LMMSE

Original problem (coupled): \[\hat{\mathbf{X}} = K_{\mathbf{XY}} K_{\mathbf{YY}}^{-1} \mathbf{Y}\]

Requires inverting full matrix \(K_{\mathbf{YY}}\).

After KL transform:

- Transform: \(\mathbf{Z} = U^T\mathbf{X}\), \(\mathbf{W} = V^T\mathbf{Y}\)

- Covariances become diagonal

- Decouples LMMSE:

\[\hat{Z}_i = \frac{\text{Cov}(Z_i, W_i)}{\text{Var}(W_i)} W_i\]

Each component solved independently.

Computational advantage:

- Original: \(O(p^3)\) for matrix inversion

- KL approach: \(O(p^2)\) for eigendecomposition, then \(O(p)\) for solution

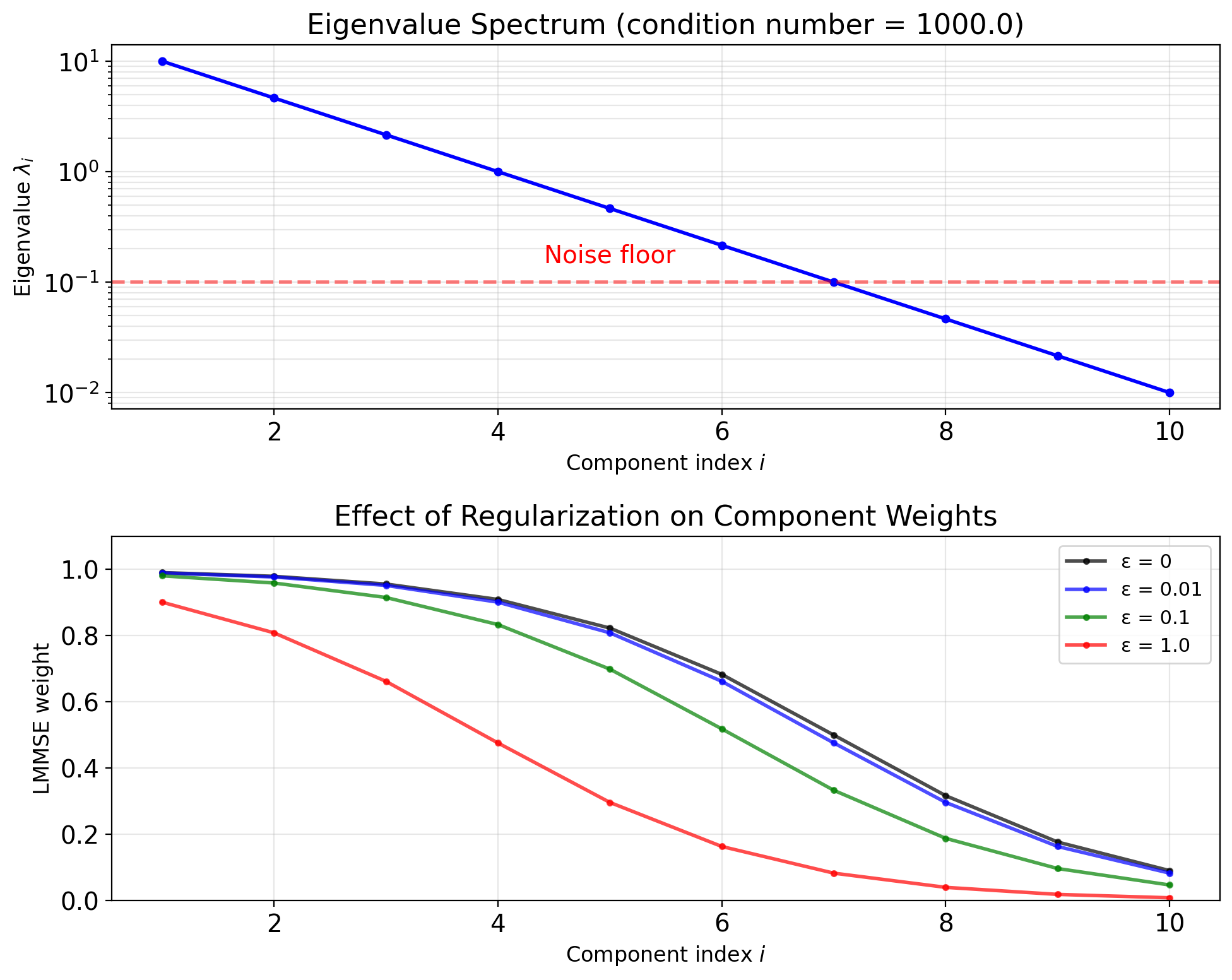

Numerical stability: Small eigenvalues → regularization: \[\hat{Z}_i = \frac{\text{Cov}(Z_i, W_i)}{\lambda_i + \epsilon} W_i\]

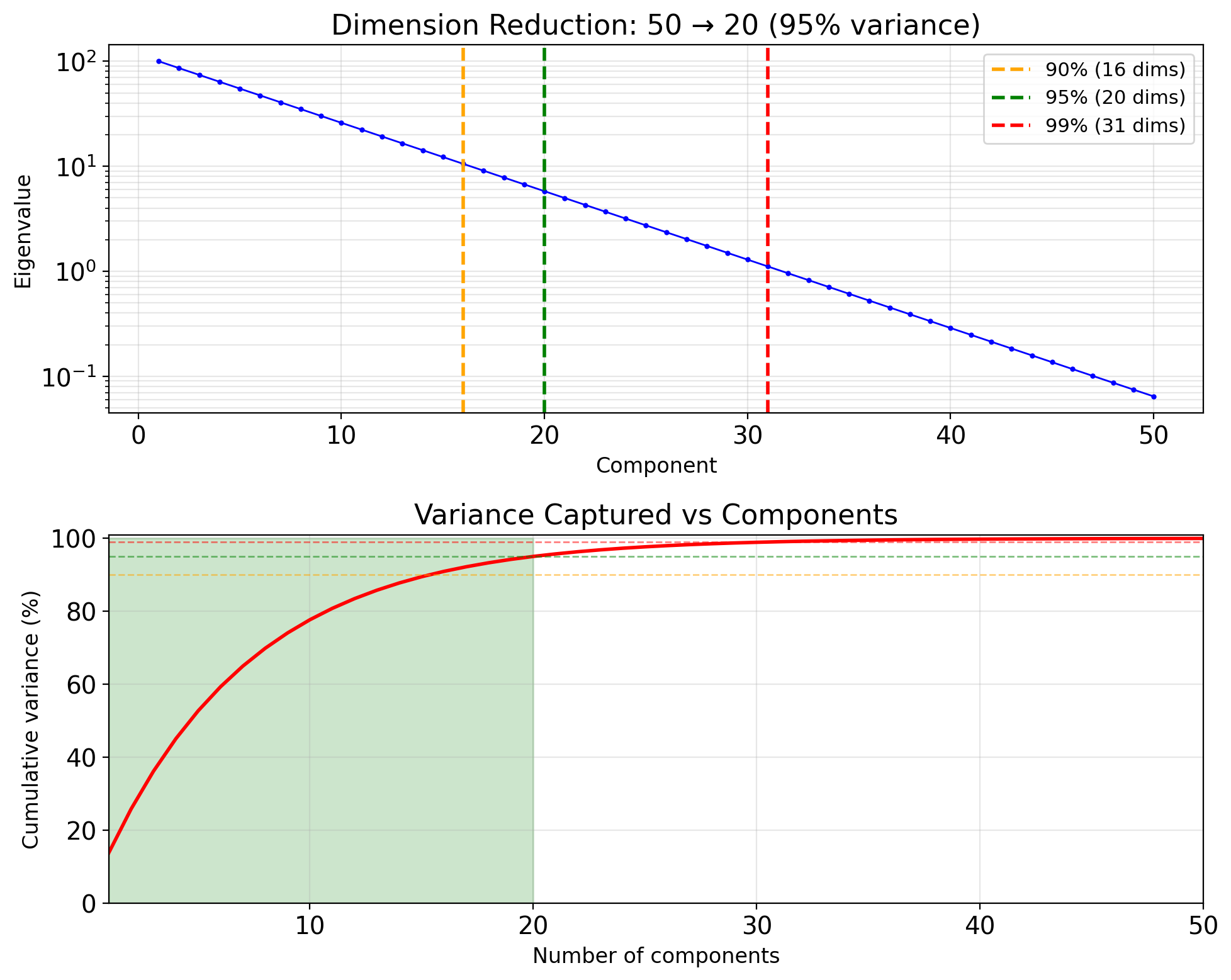

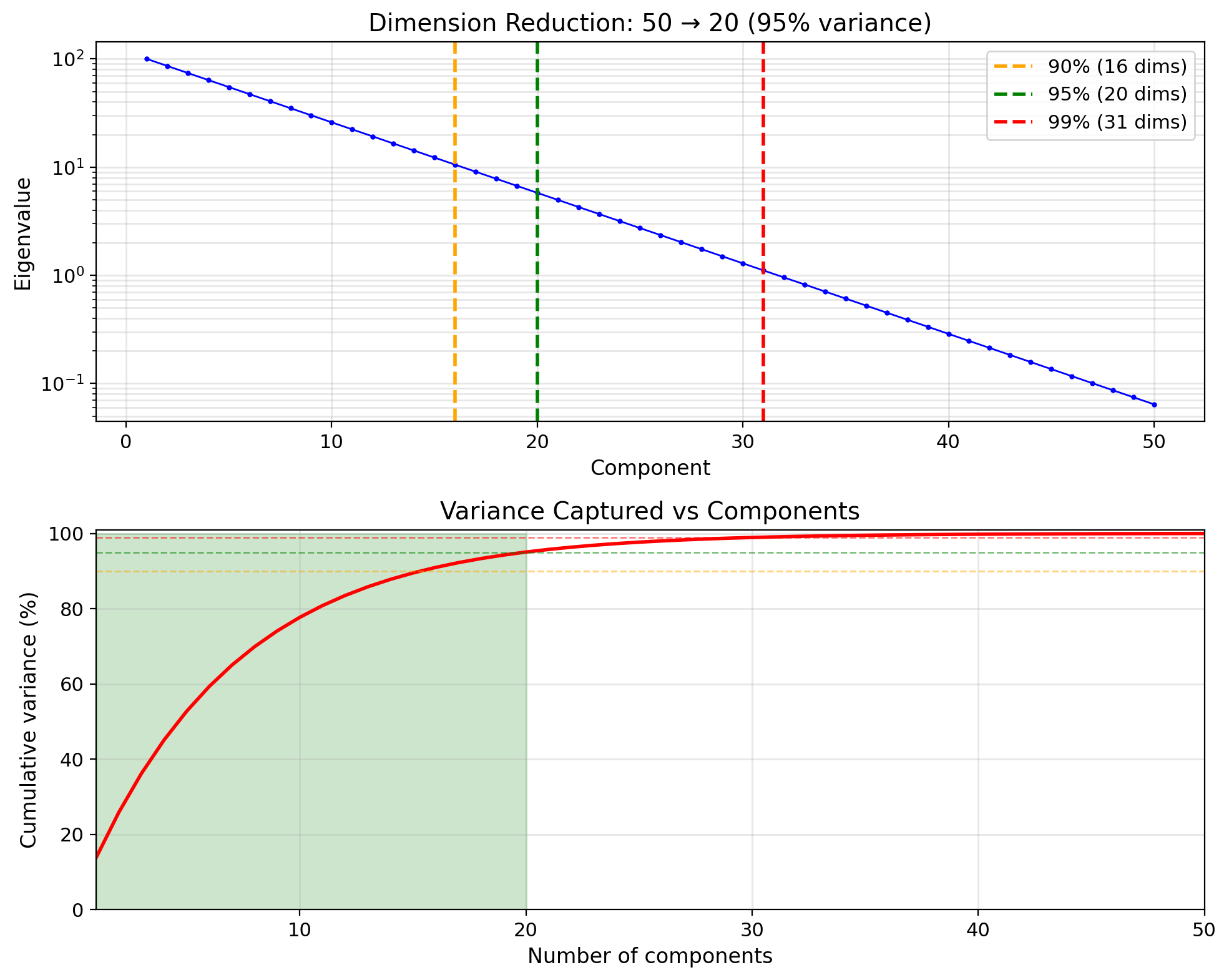

Discarding Small Eigenvalues Trades MSE for Dimension

Not all dimensions equally informative

Eigenvalues measure variance (information) per dimension.

Truncated representation: Keep only first \(k < p\) components: \[\mathbf{X} \approx \sum_{i=1}^k Z_i \mathbf{u}_i\]

Selection criterion: Retain fraction \(\alpha\) of total variance: \[\frac{\sum_{i=1}^k \lambda_i}{\sum_{i=1}^p \lambda_i} \geq \alpha\]

Common choice: \(\alpha = 0.95\) or \(0.99\)

Reconstruction error: \[\mathbb{E}[\|\mathbf{X} - \hat{\mathbf{X}}_k\|^2] = \sum_{i=k+1}^p \lambda_i\]

Error equals sum of discarded eigenvalues.

Applications:

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

- Data compression

- Denoising (discard noisy dimensions)